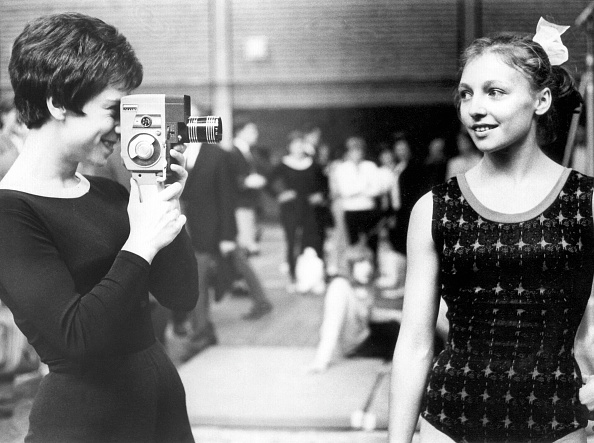

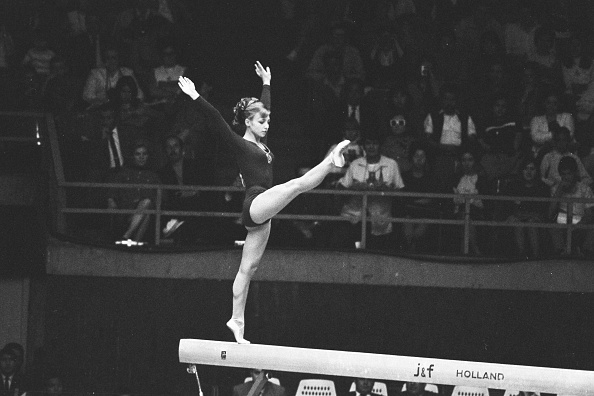

Few gymnasts captured the imagination of fans quite like Natalia Kuchinskaya, the so-called “Bride of Mexico,” whose charm and artistry made her one of the most beloved figures of the 1968 Olympic Games. Though she stepped away from competition shortly thereafter, the memory of her performances lingered for years, with admirers hoping she might one day return to the floor. Instead, her path took her far beyond medals and routines—almost to the circus ring. But ultimately, she returned to the sport in a new role: coach and mentor to a new generation of gymnasts in Kyiv.

In this 1987 interview, Kuchinskaya reflects on her journey from teenage prodigy to thoughtful coach, offering insights into the challenges of children’s sports, the dangers of overemphasizing technical difficulty at the expense of artistry, and the responsibility coaches have to raise not only athletes but also well-rounded human beings. She speaks with both honesty and warmth about her own missteps, her admiration for Věra Čáslavská, her pride in Ukrainian gymnasts like Oksana Omelianchik, and her belief that gymnastics, at its core, is not just competition but happiness born of dedication and love.

Champions of the Past: A Look at Today

Natalia Kuchinskaya: “Gymnastics Is My Love”

She entered every home from the television screen as someone close and familiar. She remains for us the charming “Bride of Mexico.” It was there, at the 1968 Olympics, that her fame became worldwide. But just a year later, she left gymnastics. Still, for many years, fans kept waiting for a miracle… Everyone so wanted to see the captivating performances of Natalia Kuchinskaya again.

— Natalia, for a long time after you left elite sports, gymnastics fans hoped: what if Kuchinskaya returns to the competition floor…

— Unfortunately, that could not happen. I was very tired; I felt empty. At that time, I was re-evaluating my values. When I was competing, I felt like just a girl, a schoolchild. Sports seemed to me like a youthful passion to which I gave all my emotional strength.

When I finished competing, I was ready to do anything—just not sports. One day, I dreamed of journalism, another of studying psychology, and then I became fascinated with the stage. I even prepared an acrobatic act for the circus. For some reason, it seemed to me that sports for “adults” were something unserious. But when I had finally decided to become a performer and everything was ready for me to go into the ring, I suddenly remembered my sporting past—when competing, I never thought about success before the audience, but about the honor of my country. It struck me then that sport is an important social sphere of human life! I wanted to return to it, and I went to the Central Children’s Sports School in Kyiv, where I still work now, coaching young gymnasts.

— Do you enjoy your work?

— Very much! Although it wasn’t simple at first. For a long time, I couldn’t understand what those little ones wanted from me—those girls who came running into the gym, staring wide-eyed at the coach. I came to the school, dutifully worked my hours, and rushed home, trying quickly to forget all the “production” problems. To be honest, I didn’t get the slightest pleasure from my work.

But then something shifted inside me—I began to hurry not from work but to work! I wanted to see my girls all the time, to teach them everything I knew how to do myself, and everything modern gymnastics required! I grew to love them, and now I can’t imagine myself without them! Perhaps family traditions played a role, too: my father, my mother, and my sister are all coaches.

— What kind of gymnastics do you envision for your pupils?

— Very harmonious. Let’s be frank: in recent years, we have lost much of our artistry, we have gone down the path of technical complication, and as a result, we’ve become uninteresting to spectators. Do you know how far this has gone? I recruit a group, invite a girl, and her parents say: “What! Artistic gymnastics? It’s dangerous!” And they forget that gymnastics is also an art. That hurts me deeply!

I think this happened because gymnastics lost its spirit, its emotional intensity. It’s true that lately some interesting girls have begun to appear. First and foremost, there is Oksana Omelianchik, a student at the Kyiv school, Olga Strazheva, a young gymnast from Zaporizhzhia, and Svetlana Baitova from Mogilev, who is also quite promising.

— What goal do you set for yourself as a coach?

— To raise the girls to be good people! In sports, especially children’s sports, there are specific problems. Children must train for many hours a day to achieve high results. These hours are sometimes taken at the expense of reading, theater, and communication with friends. Some develop a kind of “sporting fanaticism.” That is what I fear most of all. While our pupils are small, they don’t understand the diversity of the world—they are “locked in” in their clubs. Perhaps that’s not so bad—it keeps them off the streets. But children grow up, and they have to part with gymnastics. And it turns out that they’ve fallen behind many of their peers—they’re less educated, they know life less well. And by then they’re already twenty years old… Catching up is much harder than keeping pace.

— So if a girl comes to you and says she has a ticket to the theater, but the performance is at the same time as training, would you let her go?

Of course, but… only if tickets don’t start “appearing” every day. The concept of a “good person” includes not only education, but also diligence, conscientiousness, and honesty. And if you have decided to take sports seriously, then you must be willing to make sacrifices.

— Do you have “favorites”?

Like every teacher does, though not everyone admits it. I love sincere, cheerful, hardworking girls, and I can’t stand dishonesty in children. I give my “favorites” more attention, spend more time with them, demand more of them…

— Today, the question of young people’s leisure time is a pressing one. Can sports help your girls stay on the right path—not only now, when they spend almost all their free time in the gym, but later, when they are adults?

— I don’t know. I would very much like for them to remain pure and whole, but I can’t guarantee it. You see, elite sports are in some sense cruel. While you are on top, showing good results, everyone needs you. But once an athlete leaves the arena, she is forgotten at once. And in gymnastics, the peak comes at 15–16 years old, when the girl hasn’t yet formed as a person, and suddenly applause, flowers, and praise fall onto a child’s head. From this, she develops, I would say, a sense of her own exceptionalism, an egoism. And at 20, she ends her career, and attention evaporates as if it had never been. The gymnast becomes like everyone else—or even a little worse, since she didn’t have time to finish the book everyone else has read because she rushed to training; she missed the movie everyone saw because she was at a competition; she hadn’t thought about her future profession, which others had already chosen.

— Are you against elite sports?

— No, not against. But somehow one has to try to protect children from its downsides—serious injuries, psychological overload. Above all, one must preserve the human being in the child, and only then the athlete. Then maybe it will be possible to soften the blow that awaits them in the future when they part with the sport. How to do this, I don’t know.

— How do you recruit your groups?

— First, we take everyone who wishes to come. By the way, sadly, there aren’t many. Then, after a year or two, comes the first selection, since our school is specialized.

— What is your criterion for this?

— Diligence and focus. I believe you can “teach” a child gymnastics if she wants it. Though no one is safe from mistakes. When I first saw Oksana Omelianchik, I decided nothing would come of her. She was running around the gym, not listening to the coach, frolicking as much as she could. Fortunately, I was wrong. She is one of the most interesting Soviet gymnasts today.

— Do you have pupils who might make their mark in sports in the future?

— It’s too early to say. I have an interesting girl—Lena Bandolish—and if she has the willpower to follow the whole difficult path that leads to victory, then I hope someday we will hear of her. But for now, she is still a child, and I don’t want to guess so far ahead.

— Is there an ideal in gymnastics for you, someone you yourself would have aspired to and whom you would hold up for your pupils?

— I think girls don’t need an idol. Let them remain themselves. For me, the ideal is probably Věra Čáslavská of Czechoslovakia. I was never able to beat her, though I wanted to very much. She was an amazingly strong, determined, and serious gymnast. And at that time, as I’ve already said, I treated sports like a hobby. I think that hindered me. Any work must be done with full commitment.

— What problems concern Coach Kuchinskaya today?

— The first and main one: there are too few gymnastics halls in Kyiv. For a large city to have only two good halls for children means, at the very least, condemning artistic gymnastics to stagnation. And when I say two halls, I’m even exaggerating: one belongs to a sports boarding school, and only their students train there. In fact, for children “from the street” there is only one hall, in the Palace of Sports, where we are literally on top of each other. I very much hope this problem will somehow be solved.

The second, strangely enough, is parental overprotectiveness. Many of them, for some reason, think: if a girl is slender, then she must be sick. I start to explain that excess weight is a direct road to injury. They nod, they smile, they seem to agree. Training ends, I walk home, and a hundred meters from the Palace of Sports, hidden in the bushes, a solicitous mother is feeding her child a buttered roll. They see me: “Oh, there’s no hiding from you!” How can I explain to them that they are harming their own daughter?

— And do you believe your girls need you?

— Not only do I believe it, I know it! And not out of coaching ambition. Gymnastics today is so difficult that a gymnast simply cannot manage without her coach. What once seemed the “limit” of difficulty is today performed by an ordinary lower-level competitor. The coach–pupil bond is extremely delicate. When, for example, Margarita Irshenko is on an apparatus and I am watching her closely, she performs everything cleanly and easily. Let me get distracted for just a second, and Rita either falls or makes an unforgivable mistake.

— Natalia, you are not only a coach, but a judge…

— In the judging of our sport, there are, in my view, so many problems; it’s impossible to count. I think the most important thing is that we still don’t evaluate artistry. It seems to me that it would make sense to revise some rules and somehow introduce a score for the impression made by the performance.

— So what does artistic gymnastics mean to you?

— In my understanding, gymnastics is happiness born of honest, selfless work…

N. Kalugina. (Our special correspondent). Kyiv–Moscow.

ЧЕМПИОНЫ ПРОШЛОГО: ВЗГЛЯД В СЕГОДНЯ

Наталья КУЧИНСКАЯ: Гимнастика — любовь моя

Она входила с телеэкранов в каждый дом близким нам человеком. Она по-прежнему для нас очаровательная «невеста Мехико». Там, на Олимпиаде-68, её слава стала всемирной. Но через год она ушла из гимнастики. Однако ещё много лет болельщики ждали чуда… Всем так хотелось увидеть пленительные выступления Натальи Кучинской.

— Наташа, долгое время после того, как вы покинули большой спорт, любители гимнастики надеялись: а вдруг снова на помост выйдет Кучинская…

— К сожалению, этого произойти не могло. Я очень устала, чувствовала себя опустошённой, для меня в то время шла переоценка ценностей. Когда я выступала, чувствовала себя совсем девчонкой, школьницей, спорт мне казался чем-то вроде юношеского увлечения, которому я отдала все душевные силы.

Закончив выступления, я была готова заниматься чем угодно, лишь бы не спортом. То мечтала о журналистике, то изучала психологию, то увлеклась сценой. Даже подготовила акробатический номер в цирке. Мне почему-то казалось, что спорт для «взрослых» людей — это нечто несерьёзное. Но когда я окончательно решила стать артисткой и всё было готово для того, чтобы выйти на манеж, вспомнила своё спортивное прошлое, когда, соревнуясь, я думала не об успехе перед зрителями, а о чести страны… Меня тогда озарило, что спорт — это важнейшая социальная сфера человеческой жизни! Мне захотелось вернуться в спорт, и я пошла в Центральную детскую спортивную школу в Киеве, где работаю и сейчас, тренирую юных гимнасток.

— Вам нравится ваша работа?

— Очень! Хотя складывалось всё непросто. Долгое время я не могла понять, что же нужно от меня этим малышкам, которые прибежали в зал и во все глаза смотрят на тренера. Я приходила в школу, честно отрабатывала необходимые часы и убегала домой, стараясь побыстрее забыть о «производственных» проблемах. По правде говоря, не получала ни малейшего удовольствия от своего труда.

А потом произошёл какой-то внутренний перелом — я стала спешить не с работы, а на работу! Мне захотелось постоянно видеть моих девочек, научить их всему, что умела делать сама, и тому, что требует современная гимнастика! Я полюбила их, и сейчас не представляю себя без них! Может быть, тут сказались и семейные традиции: у меня и папа, и мама, и сестра — тренеры.

— Какой вы видите гимнастику для своих воспитанниц?

— Очень гармоничной. Что греха таить, за последние годы во многом мы потеряли артистичность, пошли по пути технического усложнения и в результате оказались неинтересными для зрителей. Вы знаете, до чего дело дошло? Набираю группу, приглашаю девочку, а мне родители говорят: «Что вы! Спортивная гимнастика! Это же опасно!» А о том, что гимнастика — это ещё и искусство, забывают. Мне очень обидно!

Я думаю, произошло это из-за того, что гимнастика потеряла духовность, исчез эмоциональный накал. Правда, в последнее время стали появляться интересные девочки. В первую очередь это воспитанница киевской школы Оксана Омельянчик, молодая гимнастка из Запорожья Ольга Стражева, неплохо смотрится Светлана Баитова из Могилёва.

— Какую задачу вы ставите перед собой как тренер?

— Вырастить из девочек хороших людей! В спорте, особенно детском, есть свои проблемы. Дети должны тренироваться по многу часов в день для достижения высоких результатов. Эти часы выкраиваются порой за счёт чтения, театра, общения с друзьями. У некоторых вырабатывается этакий «спортивный фанатизм». Вот этого я боюсь больше всего. Пока наши ученицы маленькие, они не понимают многообразия мира, «замкнуты» в секции, и это для них, может быть, и неплохо — по крайней мере, они не «на улице». Но дети вырастают, и приходится прощаться с гимнастикой. И оказывается, что они отстали от многих сверстников — и образованны хуже, и жизнь знают плохо. А ведь им будет уже по двадцать лет… Догонять гораздо труднее, чем идти в ногу.

— Значит, если к вам подходит девочка и говорит, что у неё есть билет в театр, а спектакль идёт в одно время с тренировкой, вы её отпустите?

— Конечно, но… если билеты не станут «появляться» каждый день. В понятие «хороший человек» входит не только образованность, но и трудолюбие, добросовестность, честность. И если уж решила серьёзно заниматься спортом, то изволь идти на жертвы.

— У вас есть «любимчики»?

— Как и у всякого педагога, но не все в этом признаются. Люблю девчонок искренних, весёлых, трудолюбивых, ненавижу в детях лживость. «Любимчикам» уделяю больше внимания, больше с ними занимаюсь, больше с них требую…

— Сейчас остро стоит вопрос досуга молодёжи. Может ли спорт помочь вашим девочкам не сбиться с правильного пути не только сегодня, когда они почти всё свободное время проводят в зале, но и в дальнейшем, когда они станут взрослыми?

— Не знаю, очень хотелось бы, чтобы они остались чистыми и цельными, но поручиться за это не могу. Понимаете, большой спорт в каком-то смысле жесток. Пока ты «на коне», пока показываешь достойные результаты, ты нужен всем. Но вот спортсмен покинул спортивную арену, и тут же о нём забывают. А в гимнастике расцвет наступает в 15—16 лет, то есть тогда, когда девочка ещё не сформировалась как личность, и на детскую голову сваливаются аплодисменты, цветы, хвалебные статьи. У девочки из-за этого формируется, я бы сказала, комплекс собственной исключительности, появляется эгоизм. А в 20 лет она заканчивает выступать, и внимание к ней улетучивается, как будто его и не было. Гимнастка становится такой, как все, даже чуточку хуже, так как книжку, которую все прочли, она дочитать не успела — спешила на тренировку, фильм, который все посмотрели, она не видела — была на соревнованиях, о будущей профессии, которую другие уже избрали, она не задумывалась.

— Вы против большого спорта?

— Нет, не против. Но как-то надо постараться уберечь детей от его издержек — тяжёлых травм, психологических перегрузок. Надо, в первую очередь, сохранить в детях человека, а потом уже спортсмена. Тогда, может быть, удастся смягчить этот удар, который ожидает их в будущем при расставании со спортом. Как это сделать, я не знаю.

— Как вы проводите набор в группу?

— Сначала берём всех желающих. Кстати, их, как ни горько признавать, немного. Потом, через год-два, идёт первый отсев, ведь школа у нас специализированная.

— Какой у вас критерий при этом?

— Трудолюбие и собранность. Я верю в то, что можно «научить» ребёнка гимнастике, если он того хочет. Хотя от ошибок никто не застрахован. Я, когда первый раз увидела Оксану Омельянчик, решила, что из неё ничего не получится. Она носилась по залу, тренера не слушалась, резвилась как могла. К счастью, я ошиблась. Она одна из самых интересных советских гимнасток на сегодняшний день.

— У вас есть ученицы, которые в будущем могли бы сказать своё слово в спорте?

— Пока об этом говорить рановато. У меня занимается интересная девочка — Лена Бандолиш, и если у неё хватит силы воли пройти весь нелёгкий путь, который ведёт к победам, то, я надеюсь, мы когда-нибудь о ней услышим. Но пока она ещё совсем ребёнок, а загадывать так далеко я не хочу.

— Есть ли для вас в гимнастике идеал, к которому вы стремились бы сами и равняли бы на него своих воспитанниц?

— Думаю, что девочкам не нужен кумир. Пусть остаются самими собой. Для меня же идеал, пожалуй, Вера Чаславска из Чехословакии. Я так и не смогла у неё выиграть, хотя очень хотела. Это удивительно сильная, волевая, серьёзная гимнастка. А я в то время, как я уже говорила, относилась к спорту как к хобби. Думаю, это мне и помешало. Любое дело надо делать с полной отдачей.

— Какие проблемы волнуют тренера Кучинскую?

— Первая и основная: в Киеве мало гимнастических залов. Для большого города иметь только два хороших зала для детей по меньшей мере означает одно — обречь спортивную гимнастику на прозябание. Причём, когда я говорю о двух залах, я даже преувеличиваю — один из них принадлежит спортивному интернату, и там тренируются только их ученики. Фактически для детей «с улицы» функционирует только один зал у нас во Дворце спорта, где мы буквально ходим друг у друга «на головах». Очень надеюсь, что эта проблема как-то будет решена.

Вторая, как ни странно, — это мнительность родителей. Многие из них почему-то считают: если девочка худенькая, значит, она больна. Начинаю доказывать, что лишний вес — это прямой путь к травмам. Вроде все понимают, кивают головой, улыбаются. Кончается тренировка, иду домой, а в ста метрах от Дворца спорта, спрятавшись в кустах, сердобольная мама потчует своё чадо булкой с маслом. Видят меня: «Ой, от вас нигде не спрячешься!» Как объяснить им, что они вредят собственной дочери?

— А вы верите в то, что нужны вашим девочкам?

— Не только верю, но знаю, что это так! И вовсе не из-за тренерской амбиции. Гимнастика сейчас настолько сложна, что спортсменка просто не может обойтись без своего тренера. То, что нам казалось «потолком» трудности, сегодня выполняет простая разрядница. Поэтому связь тренер — ученик чрезвычайно тонка. Когда, например, Маргарита Иршенко работает на снаряде и я за ней внимательно слежу, она всё исполняет чисто, легко. Стоит мне хоть на секунду отвлечься, Рита либо падает, либо допускает непростительные огрехи.

— Наташа, вы ведь не только тренер, но и судья…

— В судействе в нашем виде спорта столько проблем, на мой взгляд, что не перечесть. Я думаю, самая важная заключается в том, что мы пока не оцениваем артистичность спортсменки. Мне кажется, что имело бы смысл пересмотреть некоторые правила и ввести каким-то образом оценку за впечатление от выступления.

— Так что же такое спортивная гимнастика для вас?

— В моём понимании гимнастика — это счастье от честной, самоотверженной работы…

Фото Б. Светланова.

Н. КАЛУГИНА. (Наш спец. корр.). КИЕВ МОСКВА.

More Interviews and Profiles

One reply on “1987: An Interview with Natalia Kuchinskaya – “Gymnastics Is My Love””

I love these interviews you’ve found and posted recently. Thank you for all your hard work!