For many Western gymnastics fans, Chinese gymnastics can feel like a black box—a program that produces world-class results while remaining largely opaque to outside observers. Articles like this one, from the state-run People’s Daily on the eve of the 1999 World Championships in Tianjin, offer a rare window into how Chinese coaches and journalists understood their own program’s strengths, limitations, and ambitions.

The men’s team, averaging under 20 years old and led by Huang Xu, Yang Wei, and Lu Yufu, was tasked with defending the team title won in Lausanne two years earlier. Coaches were frank that a repeat blowout was unlikely; Russia had studied the loss and had come prepared. But the program was deep enough across all six apparatus that a second consecutive gold remained the explicit goal.

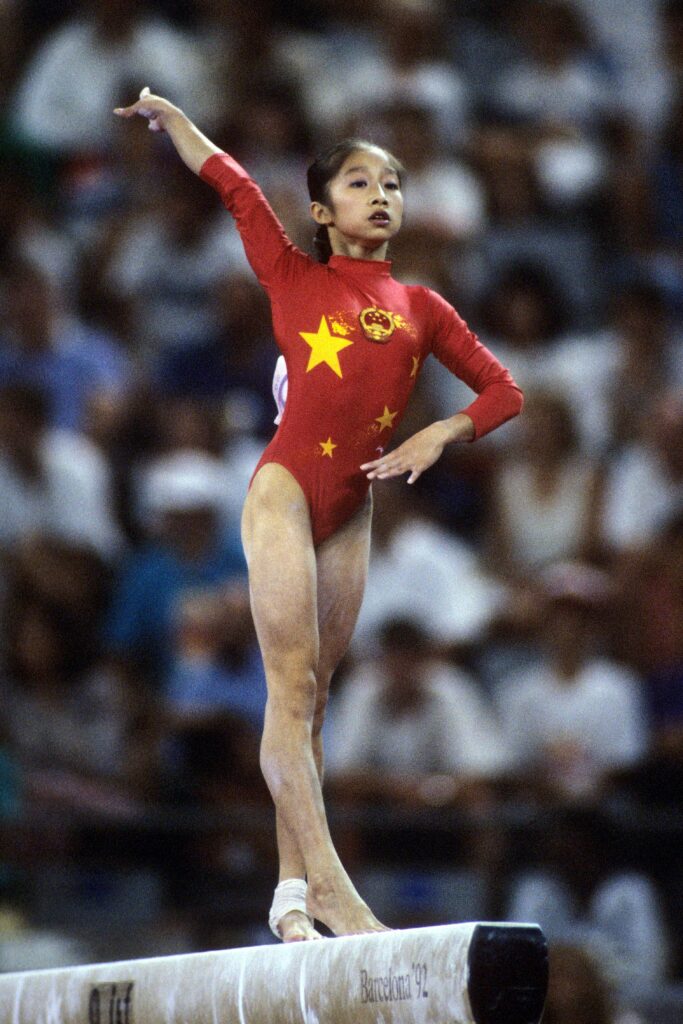

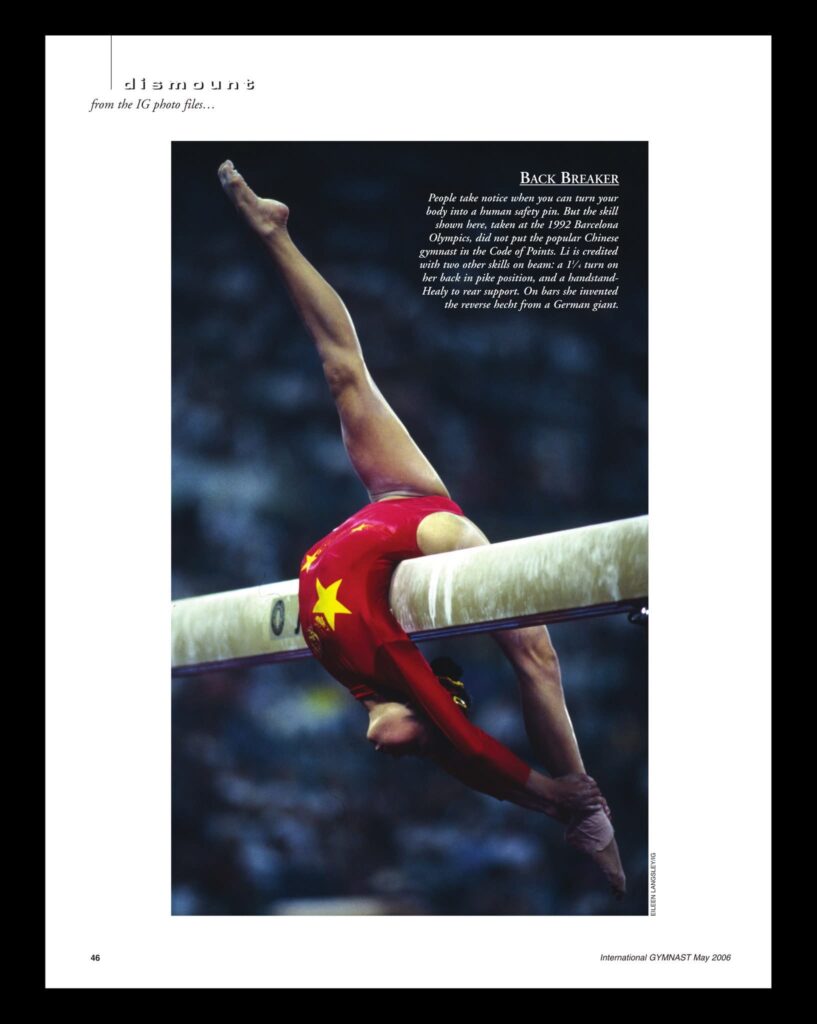

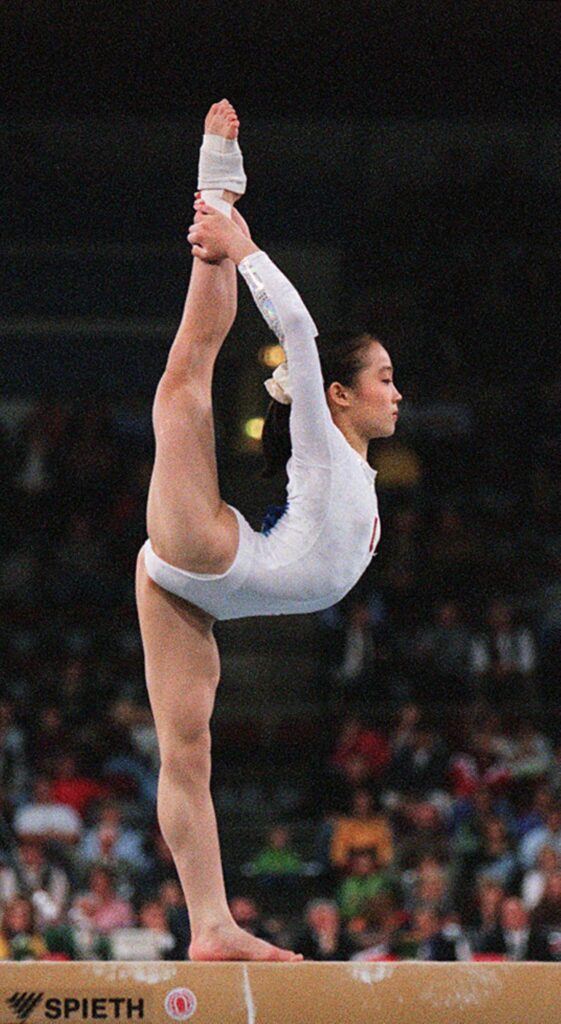

The women’s team entered under different expectations and with a striking demographic fact embedded in the preview coverage. The squad’s average age was just 16, the precise minimum required for senior international competition under FIG rules. Only Liu Xuan had previous World Championships experience; the other six were making their debuts. Coaches quietly acknowledged that Romania and Russia were out of reach and framed the real contest as a three-way battle for bronze against the United States and Ukraine. For the balance beam final, China deployed what it called the “5-2-1 plan”: field five gymnasts capable of winning, ensure at least two reach the top eight, and convert one into a champion.

The full article, translated below, appeared in the pages of People’s Daily on October 9, 1999.

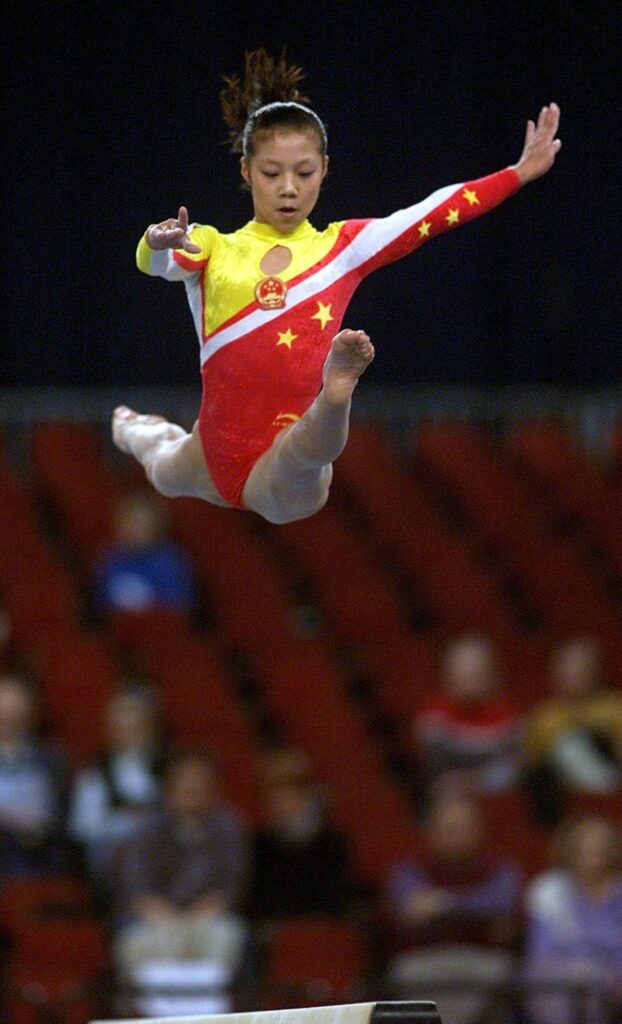

Dong was a member of the 1999 team that later lost its bronze medal after the FIG determined that she had been born in 1986, meaning she was only 13 at the time of the competition in Tianjin.