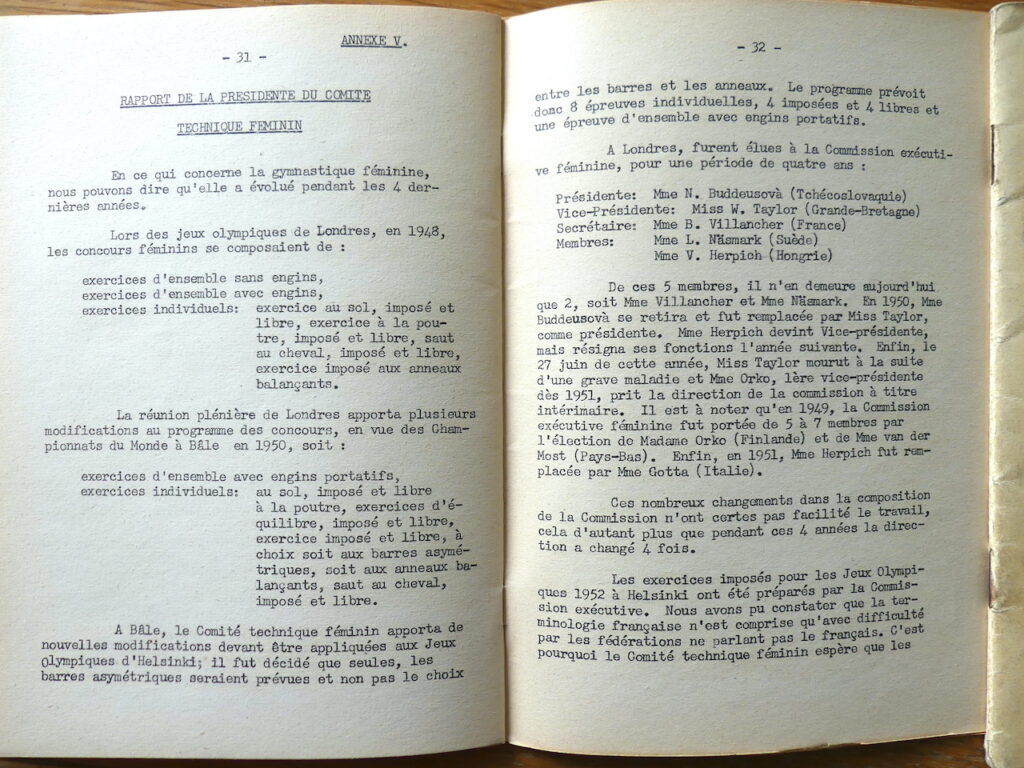

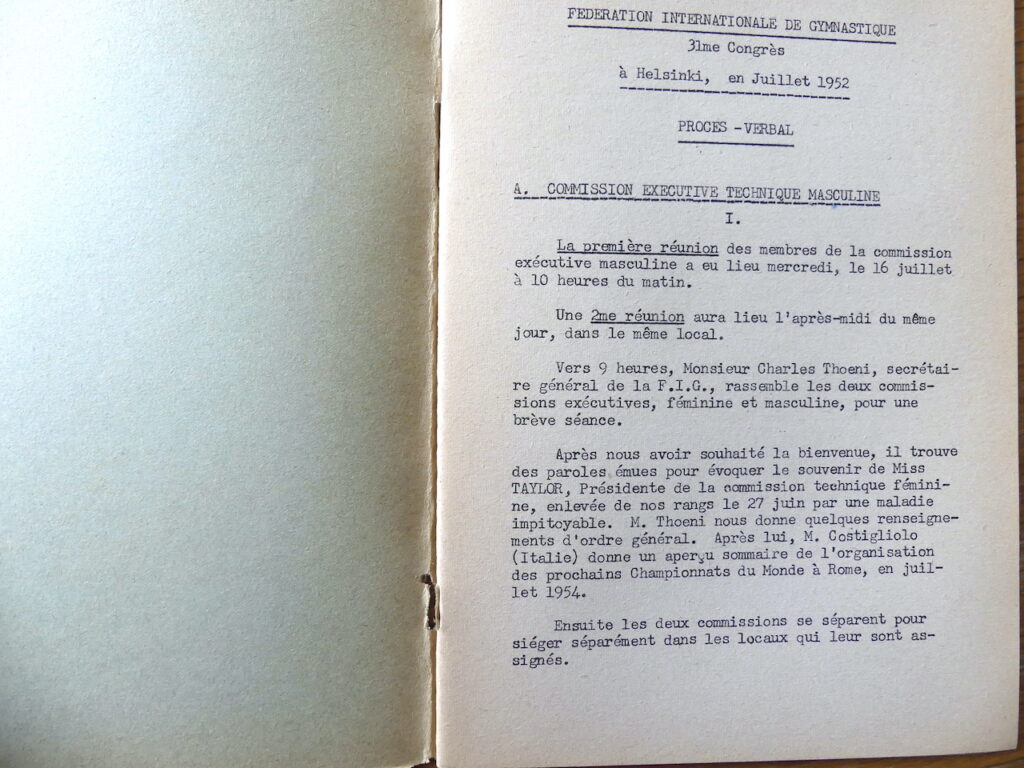

In 1948, Marie Provazníková—then president of the Women’s Technical Committee (WTC)—defected to the United States after the London Olympics, marking the beginning of a turbulent period for the committee. The 1952 report from the WTC President reflects many of the changes that followed.

Yet despite the leadership instability, participation in women’s gymnastics grew significantly between 1948 and 1952. The committee saw it as their responsibility to ensure that this growth served the “health, joie de vivre, and general well-being” of “lady gymnasts.” (Which, to modern readers, probably makes us roll our eyes a bit.)

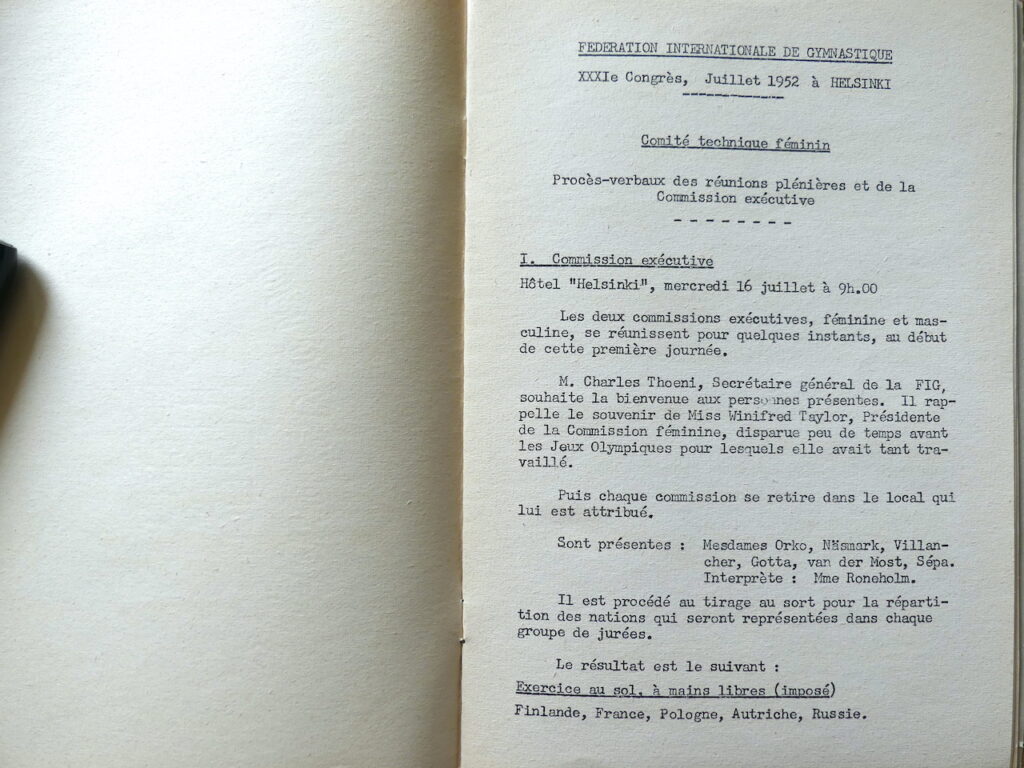

Enjoy this translation of Liisa Orko’s 1952 report.