When the German Democratic Republic collapsed in 1990, thousands of coaches, doctors, trainers, and officials from its elite sports system entered a unified Germany that was still trying to understand what, exactly, the GDR had been. Their reputations now depended on how their pasts were interpreted—by newspapers, by athletic federations, by former teammates and rivals, and sometimes by courts. Some sought to defend themselves through interviews. Others tried to fight damaging statements in court. Still others discovered that defending themselves was complicated by missing documents, conflicting testimony, or shifting expectations in a country still learning to read its own history.

Three figures from GDR gymnastics—Ellen Berger, Klaus Köste, and Gudrun Fröhner—each confronted the same problem: how to assert their own account of the past in a new Germany where the rules, the evidence, and even the moral categories were changing under their feet. Their cases did not follow the same path, nor did they end in the same place. But all three illustrate how difficult—and sometimes impossible—it was to clear one’s name in the 1990s and beyond.

Ellen Berger: Defending a Legacy in an Antagonistic Climate

In late February 1992, Ellen Berger received a letter at her home in Strausberg from the German Gymnastics Federation (DTB). Berger, who had coached the GDR women’s team from 1958 to 1976 and went on to lead the FIG Women’s Technical Committee, opened it to find a formal questionnaire asking her to declare that she was never affiliated with the State Security service.[1] She was taken aback. “I’m not easily thrown off balance,” she told a reporter later that spring, “but I was truly shocked.”

What made the request confusing was its timing. Just three months earlier, Berger had already been questioned in person by the DTB presidium in Hamburg. She recalled that meeting as “a pleasant, open, and friendly conversation,” one in which she “could speak honestly and with a clear conscience.” The DTB had cleared her and forwarded her candidacy for another term as President of the Women’s Technical Committee of the International Gymnastics Federation (FIG). She had not expected the matter to return.

But it did—and now in writing, with sharper legal edges.

What Berger’s media interviews did not mention was that her questionnaire reflected a broader administrative shift. In the wake of reunification, the Reiter Commission—tasked in 1991 with advising how to handle doping and past misconduct—had recommended that former GDR coaches, doctors, and officials be retained only if they provided written guarantees of “clean and correct behavior” in the future. Written declarations allowed federations to demonstrate due diligence without conducting full investigations at a time when opened archives, media scrutiny, and political pressure made missteps costly. Berger’s questionnaire, though not about doping, was not an anomaly. It reflected the new bureaucratic logic of the early 1990s.

To a longtime sports official, that shift could have felt deeply personal. For Berger, the second questionnaire was not a procedural safeguard but a withdrawal of trust. She signed the form but withdrew her candidacy. “My first thought was: Why is there no trust in me?” she said. “But without trust, you can’t work together.”

In explaining her decision, she pointed to a broader change in the national mood. “A lot has happened since,” she observed. Although she had never been attacked personally—“not at all by colleagues from other countries”—the atmosphere at home felt markedly different. “The climate in our own country toward officials who came from the East has grown worse.”

The forces behind that shift were visible everywhere. In gymnastics, reunification had begun with promises of partnership. But by the time the East German Turner- und Sportbund (DTV) and the West German Deutscher Turner-Bund (DTB) formally merged in 1990, the language of equality had vanished. The DTB absorbed the five new state associations from the former East, and virtually none of the DTV’s leadership made the transition. Of fifty full-time positions in the unified federation, not one went to an official from the East.

Meanwhile, in the larger world of German sport, suspicion intensified. In 1991, Doping-Dokumente exposed the scale of state-directed doping in the GDR. In 1992, the Stasi archives opened to researchers. Newspapers and magazines filled their pages with exposés and speculation. Being from the East now carried a presumption of complicity.

Outside Germany, colleagues struggled to understand her resignation. “Foreign gymnastics colleagues are completely surprised,” Berger said. “They can’t understand at all what kind of problems we have with each other here in Germany.” Their confusion reflected how specific this moment was to reunification—how much it depended on newly opened archives, political scrutiny, and an often indiscriminate suspicion that East German officials might be hiding something.

Berger herself emphasized that she was “not at all depressed.” She believed she had contributed something meaningful to the sport: expanding women’s gymnastics in countries where it barely existed, creating compulsory routines based on scientific analysis, and helping smaller nations compete internationally. That was her legacy as she understood it.

But a distinguished record could not insulate her from the pressures of the early 1990s. The problem was suspicion—ambient, structural, and persistent. Berger had done what was asked of her twice. She had answered questions, offered explanations, and signed a formal declaration. But in a climate where trust had eroded and the burden of proof fell disproportionately on those from the East, clearing one’s name meant constant questions and a legally defensible paper trail.

Faced with that reality, Berger stepped aside. Her departure was not about guilt or innocence. For her, it was about the impossibility of being believed.

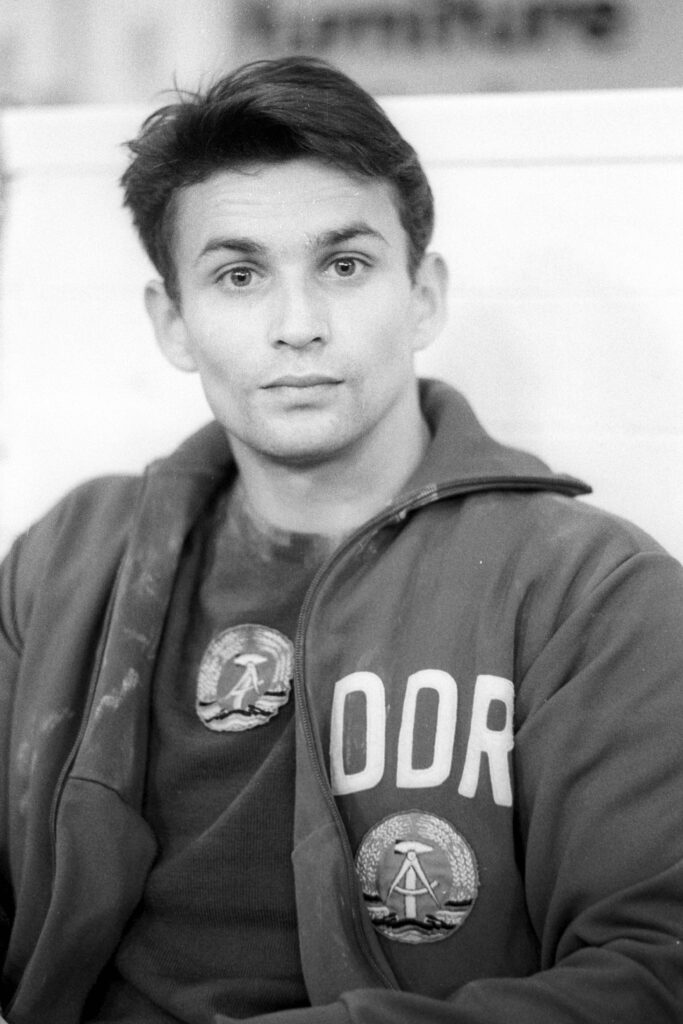

Klaus Köste: Code Name “Michael Voronin”

If Berger stepped back from public conflict, Klaus Köste stepped directly into it. But unlike Berger, he attempted to fight his battle in court—an effort that would do more to confirm lingering doubts than dispel them.

In 2001, Köste filed for an injunction to stop the Süddeutsche Zeitung from calling him “a doped Olympic champion and a coach who was thoroughly informed about the severe bodily injuries of his gymnasts.” In a sworn affidavit, he insisted that he had never knowingly taken doping substances as an athlete, nor had he knowingly coached gymnasts harmed by doping.

But two obstacles stood in his way.

The first was a paper trail. His Stasi file included a handwritten commitment dated April 5, 1977, in which Köste—assigned the alias “Michael Woronin,” the name of a Soviet rival—agreed to inform the Ministry for State Security about what he witnessed as a gymnastics coach. The reports showed that he had described the health conditions of the women he coached and the treatment methods used to keep them training through injury.

The second was testimonial. In response to the lawsuit, a former teammate and roommate—someone widely known in the gymnastics world—submitted a sworn statement. From 1967 to 1975, he said, national team members, including Köste, had taken Oral-Turinabol and discussed its effects openly. During the 1972 Munich Olympics, he recalled, Köste had taken Oral-Turinabol and a second substance, a brain-active hormone known as “B17,” to boost performance.

Put plainly, Köste had become an Olympic vault champion while taking performance-enhancing drugs—substances that, to be clear, were not explicitly prohibited by the IOC in 1972.

Once the sworn testimony and Stasi file were before the court, Köste withdrew the lawsuit, telling Neues Deutschland that he would abandon “further attempts to find out the truth, because I am certain these spirals of lies are endless.” The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung offered another interpretation, noting that, “after reading his opponents’ brief, Köste was apparently not entirely confident he could win the case.”

Yet withdrawal did not end his life in the world of gymnastics. Despite the Stasi file and sworn testimony, the German Gymnastics Federation brought him on as a volunteer adviser for the 2002 German Gymnastics Festival in Leipzig. DTB President Rainer Brechtken defended the decision, arguing that Köste had “revealed himself to us” and that, as a coach, he had “only reported on the health condition of his gymnasts”—a process Brechtken described as routine. Most importantly, “Köste is not employed by us as a trainer,” he said; he was simply one of thousands of unpaid volunteers supporting the festival. The line the DTB drew was clear: a Stasi past and allegations of doping complicity did not bar someone from taking on temporary, unpaid work.

But even this limited role could not sever him from his past. The record remained, ready to resurface whenever his name did. When he died suddenly in 2012 at 69, the Mitteldeutsche Zeitung obituary honored his athletic achievements—vault gold, three Olympics, thirty-four national titles—but still noted that he had once been “assigned the cover name ‘IM Michael Woronin’ by the Ministry for State Security.” His achievements remained indisputable; his past, inescapable.

Köste could outlive the system that created the codename, but not the codename itself.

Gudrun Fröhner: The Case Defined by Absence

If Berger’s challenge was political and Köste’s legal, Gudrun Fröhner’s was epistemological. Her attempt to clear her name unfolded in courtrooms where some of the most important documents were precisely the ones nobody could produce.

In January 1998, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung reported that microbiologist Werner Franke had identified two entries in a classified catalog of GDR literature on “supporting means” (unterstützende Mittel)—East Germany’s euphemism for doping. The catalog listed two studies on gymnastics, dated 1978 and 1980, under the name of Gudrun Fröhner, who had served as team doctor for the GDR gymnastics federation from 1977 to 1985. Franke had access to the catalog. Neither he nor historian Giselher Spitzer, however, had the studies themselves; the works had not been found.

In the litigation that followed, both men relied on other once-classified material. A steroid report by endocrinologist Winfried Schäker and a dissertation by Günter Rademacher—documents from the Leipzig Research Institute for Physical Culture and Sport—each cited a study by Fröhner in connection with experiments on gymnasts in 1979 and 1980. Minutes from an elite-sport working group—later recovered by ZERV—listed Fröhner, alongside several colleagues, as responsible within the theme area “unterstützende Mittel / State Plan Theme 14.25,” a bureaucratic designation that placed her inside the GDR’s doping research structure without clarifying what, exactly, she had done. And the works by Fröhner that Schäker and Rademacher cited? They were missing. They showed up in footnotes and catalog entries, but not in the archive.

Despite this gap, Spitzer accused her publicly of complicity in human experimentation and in helping to make young athletes dependent on drugs. Fröhner responded by suing him and Franke.

Her defense shifted over time. At first, she denied having taken part in doping research. She told reporters she did not know the publications attributed to her, said she had only learned of the GDR’s doping practices in the 1980s, and insisted—later under oath—that she had protected gymnasts from both doping and extreme dieting regimens.

By the autumn of 1998, her account had become more complicated. In October, during a civil proceeding in Berlin, her lawyer, Friederike Schulenburg, confirmed that Fröhner had administered the anabolic steroid Oral-Turinabol to underage gymnasts. A few months later, at the Berlin Court of Appeal, Schulenburg added that her client had also given a steroid substance she called “STS 672” in small doses. The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung noted that she likely meant STS 646—a synthetic steroid never approved as a medication—and pointed to a statement by GDR doping doctor Manfred Höppner, who told investigators that Fröhner had collected this preparation from the Sports Medical Service in Berlin.

But Schulenburg insisted this was not doping. It was therapy, she argued—hormone preparations administered in minimal doses, according to the so-called Kaiser Schema, to counteract the catabolic effects of hunger and hard training and to prevent growth disturbances.

Fröhner, for her part, produced her own counter-evidence. She submitted an affidavit from Heinz Langer, former head of the FKS endocrinology laboratory, stating that her name had been entered on the minutes of a colloquium on doping questions without her knowledge. Her defenders also pointed to statements from thirty-three former gymnasts who said they had enjoyed working with her.

Against this backdrop of clarifications, denials, and missing documents, the courts faced a narrow question: not whether Fröhner had doped athletes, but whether Franke and Spitzer were legally permitted to say she had.

Presiding judge Michael Mauck framed it bluntly. He personally, he said, had no reason to believe that Fröhner had doped anyone. The question before the court was whether Spitzer and Franke, given the documents available to them, were allowed to believe it—and to say so in public. The court held that their statements remained permissible within the bounds of academic freedom.

In the end, her legacy remained contested: implicated by the documents that survived and shaped by the documents that never surfaced.

A Name in Pieces

These three cases showed that clearing one’s name required far more than defending oneself. It required control over the narrative itself.

In East Germany, that control had once seemed almost straightforward. The SED leadership set the line; the state media repeated it. Within that system, there was effectively one sanctioned version of events—the party’s.

But once the GDR vanished, so did its official story. And without it, interpretation fragmented. The same documents, the same actions, could now be read in sharply different ways.

For Berger, this shift felt personal. International criticism had always come with her FIG role; what stung in 1992 was mistrust at home. The DTB’s repeated questionnaires suggested that no explanation she gave could bridge the new Germany’s doubts about the old system she came from.

Klaus Köste faced a similar uncertainty. When he sued the Süddeutsche Zeitung for calling him “a doped Olympic champion” who knew about the harm done to his gymnasts, he hoped to assert his own account. Instead, his claims collided with Stasi files and conflicting testimony, and he dropped his lawsuit.

Gudrun Fröhner encountered the same logic in her defamation case against Franke and Spitzer. Her lawyer insisted she had followed legitimate medical practice when administering steroids; the court ruled the scholars could still describe her work as doping. Her professional identity and her critics’ accusations now stood side by side, equally plausible.

And then came the afterlives of these reputations.

In early 1992, when Berger withdrew her candidacy for another FIG term, the Berliner Zeitung called her “held in high esteem worldwide for her expertise.” Foreign colleagues were “completely surprised” by her resignation; they “can’t understand at all what kind of problems we have with each other here in Germany.”

But esteem was never universal. When Berger died in 1997, Evenimentul Zilei, a Romanian tabloid, ran an obituary titled: “Ellen Berger has died, the head of the jury who stole Nadia Comăneci’s Olympic title in Moscow.” Nothing about her decades of technical leadership—only the 1980 beam score, and the grievance that had never faded.[2]

For seventeen years, Berger lived with two parallel reputations: respected by colleagues who valued her expertise, condemned by those who believed they had witnessed an injustice. In Germany after reunification, she was admired yet mistrusted; abroad, in some places, reduced to a single moment.

You could answer every question. You could step back with dignity. You could be praised for your work. And somewhere else, another audience could define you entirely differently.

Once the official story disappeared, so did the hope of a single vindication. There was no uniform name to clear, no stable record to set straight—only competing memories, and the impossibility of reconciling them all.

References

“Berufsverband für Kinderheilkunde nennt Behandlung verbrecherisch: Ärztin Fröhner gibt Anabolika-Vergabe zu.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, October 21, 1998,

“Des Dopings bezichtigt: Fröhner verliert die Berufung,” Berliner Zeitung, Feb. 16, 1999.

“Funktionäre des DDR-Sports formieren sich gegen ‘Kriminalisierung.’” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, May 14, 1998.

“Ganz einfach, nur Fliegen ist schöner als Turnen.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, May 18, 2002.

“Gudrun Fröhner darf Doperin genannt werden.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, May 2, 1998.

“Historiker darf Ärztin des Dopings beschuldigen.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Feb. 17, 1999.

Krüger, Michael, and Christian Becker. “Doping and Anti-Doping in the Process of German Reunification.” Sport in History 34.4 (2014): 620-643.

Jahn, Michael. “Eine Ära im Turnen geht jäh zu Ende.” Berliner Zeitung, Mar. 12, 1992.

“Olympiasieger Köste im Alter von 69 Jahren gestorben.” Mitteldeutsche Zeitung, Dec. 15, 2012.

“Richthofen nennt Frankes Anzeige ‘skandalös und rufschädigend.’” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, June 15, 1998,

Schmeißer, Sonja. “Ellen Bergers Rücktritt als TK-Präsidentin der FIG.” Olympisches Turnen Aktuell, no. 2, Apr. 1992.

Spitzer, Giselher, and Anno Hecker. “Salto rückwärts von Vorturner Köste Stasi-Mann als Turnfest-Animateur.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, May 15, 2002.

“Unhaltbare Vorwürfe oder gefährlicher Persilschein?” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Jan. 1, 1998.

Vasilescu, Cecilia Marta. “A murit Ellen Berger, șefa juriului care i-a furat Nadiei Comăneci titul olimpic la Moscova.” Evenimentul Zilei, April 21, 1997.

Notes

- There had been rumors about Ellen Berger’s ties to the Stasi. Maria Simionescu, a member of the Women’s Technical Committee and an informant for Romania’s state security apparatus, wrote in a September 30, 1980 report for the Securitate: “This aggression manifests itself against us in particular, turning problems she might have with our representatives into problems with “Romanians” in general. For example, at Thonon les Bains, she reproaches Jaroslava Matlochová (C.S.R.) for having come to Băile Felix in our country for a cure: “How could you go to Romania, to the Romanians?” She got a very nice answer from her, telling her how well she had been received and what a special people we were. The majority of recent meetings have begun with reproaches against us openly in the Committee. At the Moscow O.G., in the finals for the beam, Titov Yuri, U.S.S.R., with a direct interest, capitulated, but not Ellen Berger. She was married and has a son who she told me works in the D.D.R. Security. For many years she’s lived with Helmut Grosse, an air force officer, who did specialist training in the U.S.S.R. They are both invited to the U.S.S.R. every year, and at the major competitions in 1979 and 1980 Grosse was invited home for dinner (all the time) by Soviet generals alone or with Ellen Berger.” Qtd. in Nadia and the Secret Police, Stejărel Olaru.

- Here’s how Sports Illustrated described Nadia’s beam routine in 1980: “Nadia began with a handstand, then a “walkover” (hand-aided flip) on the four-inch wide beam. She attempted a forward flip with a half twist, a move that’s hers alone. In it she twists in midflight, so that when she alights she is looking back at the spot from which she started. The flip took her perilously near the edge of the beam, and she wobbled for an anxious moment. A slight flaw. But she completed her exercise with a spectacular series of flips, dismounting on a double-twist back flip. She took a tiny step backward upon landing—another small flaw—but the performance had the largely pro-Soviet crowd cheering and applauding. Comaneci stood before them, hands on nonexistent hips, while the Romanian patriots chanted, “Hey, hey, Na-dee-ya!” The decision was now in the laps of the women judges.

“Until this moment, the gymnastic competition had proceeded with little incident. It now descended into chaos. The audience murmured in anticipation, but Nadia’s points did not appear on the electronic scoreboard. The yellow-bloused judges were haggling among themselves on the floor, and the crowd began to whistle in disapproval. Head judge Maria Simionescu of Romania separated herself from the argument on the floor and joined another at the officials’ table with Ellen Berger, a heroically proportioned East German who is the chief of the technical board of the International Gymnastics Federation (FIG). Federation President Yuri Titov of the U.S.S.R. was the next combatant. For 28 minutes the judges and officials wrangled, marching back and forth between the table and the videotape machines. Finally, Kolog Nonus, a member of the Moscow Olympic organizing committee, stepped briskly to the computer normally operated by Simionescu as head judge and, while she glowered at him, punched out Nadia’s score. As he did so, he was berated by the Romanian coach, Bela Karolyi, who had been arguing with everyone within earshot. The score came up 9.85. The Sports Palace fairly exploded with Russian cheering and Romanian whistling. Nadia? She was expressionless, even when Davydova, who has a teen-ager’s head on a 10-year-old body, stood above her—barely—to accept the gold. Nadia was obliged to share the silver with Gnauck.”

One reply on “Clearing Their Names: Three GDR Gymnastics Figures in a New Germany”

My comments are not in relation to the article itself but The Notes. They contain neutral third party first-hand accounts which contradict the Romanian version of events. The Romanians thought that unless they’re awarded the gold medal there was some kind of fix going on. It is that conspiratorial turn of mind, that habit to see a plot whenever things don’t go their way that led one experienced gymnastics journalist to note “The Romanian definition of biased judging is – someone else won”.

On the night of the 1980 Olympics AA final The gymnasts were divided into 4 groups of 9, each group starting on a different piece of apparatus. Formation of the groups and starting order within the groups was decided by lot. Neil Admur, New York Times, July 25 1980, A17, ”The drama on the final rotation added to the suspense. Miss Gnauck was second among the 9 gymnasts on the vault, Miss Davydova seventh on the bars and Miss Comaneci eighth on the beam”.

Roberta Conlan XXII Olympiad : Moscow 1980, Sarajevo 1984 (1998) “(Davydova) having just scored 9.95 with a beautiful performance on the uneven bars. If Comaneci, who was slotted eight on the beam, could match that 9.95 she would win the gold”.

What was Nadia thinking as she approached the beam – the bridge of sighs – as she awaited the Head Judge’s signal to her to begin ? Bela Karolyi has said of the beam “ Some call it the purgatory of the sport”. The Germans call it the Angst beam – the clutch event under ordinary circumstances – but certainly in the early days it held no fear for Nadia as she demonstrated at the 76 Olympics. But more recently there had been a few falls or fumbles – 79 Champions All, 79 Balkan Championships, 79 Europeans. At the 79 World Cup she was penalised for having too short a beam routine. Dr.Joe Massimo, IG, Feb 88, p.36, ”Most women’s competitions are won or lost on balance beam. Beam is probably the most “mental” of events”. Bill Sands “ Many an All-Around has been lost due to one tiny miscalculation on the balance beam”. In a review of the European Championships IG associate editor Lyn Moran noted August 79, p.20, and October 79, p.51, “Balance beam proved to be still a problem for Nadia, and although the judges were overly generous here, she was still assessed only a 9.35 in event finals. Her height and weight make this a more challenging proposition, where balance is of the very essence. Nadia’s wobbles and breaks during all of her last beam performances show that this is perhaps the one thing she cannot conquer…Beam, which was a forte of Nadia’s, has now become a sporadic achievement, dating back to her falls in 1978 at several competitions, and probably why she has eliminated difficulties from it”.

Nadia’s routine was very similar to her 1976 Montreal routine. She barely escalated the routine in terms of innovation and difficulty. And the old technical surety was no longer there.

Nadia needed a score of 9.925 to tie for gold or a higher score to win gold outright. The last time she had scored as high as this in an AA final was at the 1976 Olympics. Nadia scored as many 10’s on beam in Montreal as she would in the remaining 5 years and 3 months of her career. As 9.95 was the target Nadia hit this in 1 in 6 beam routines post Montreal. Out of the 100 beam optional exercises performed at the 1980 Olympics only 1 scored as high as Nadia needed – Nellie Kim’s 9.95 in the AA final, which included 2 gainer flips, 2 standing back tucks, very high leaps, elegant poses with an unique – and the most difficult performed in 1980 – dismount from one foot off a Barani into a double back somersault. What Kim did was a double somersault off one leg, while turning to face the beam. (Kim stuck her dismount. She has said it was her best beam routine of her entire career).

After one of her back flips Nadia lost her body position and had to flail her arms for balance. On her gainer bhs her turn was very late. She broke the value-raising connection between her aeriel walkover to aeriel cartwheel with a pause. Her knee bent slightly under 360 degree rotation. At the end of her routine instead of pushing off with both feet she pushed off with one and then the other. Her legs were loose/crossed on dismount and she landed slightly askew. Nadia also took a step back.

Barbara Slater,(who had represented Great Britain as a gymnast and who carried the British flag at the opening ceremonies of the 1976 Olympics, who once outscored Nadia on beam at the 1976 GBR-Romania dual meet after Nadia fell from beam is now Head of General Sport, BBC and one of the most renowned TV sports producers in the world, who orchestrated the BBC’s entire coverage of the London 2012 Olympics),was commentating live on TV and said “a definite step back on landing. That should be a 0.1 deduction but will the judges take it away ?”.

Bart Conner in “Winning the Gold”, 1985, p.110, writes “I took a step – an one tenth deduction – my score was now 9.9 tops”. On p.116 his coach, Paul Ziert writes “he took a step. This is an automatic 0.1 deduction”. On p.113 Bart writes “Lets say that an athlete has just finished a perfect routine – every move, every angle, every extension is perfect. If, when he dismounts, he steps a little to one side, that’s a 9.9. If he steps a little more off-balance that’s a 9.8. Your goal, then, is to land flat on your feet – dead center, like a pregnant elephant. We say that you stick it”.

Dudley Doust, Sunday Times, July 27 1980, ”She lurched through her routine on the beam. A 9.95 score would have given her the gold. The judges flicked their scores to the Head Judge, a Romanian, who didn’t like what she saw: 9.85. So, she simply didn’t turn it in until a long see-saw battle had ensued. That woman is a problem, said an International Gymnastics Federation official”.

Indiana Evening Gazette, July 28th 1980, p.17, ” Miss Comaneci was the last competitor going into her final exercise, the balance beam, and she needed 9.95 to beat Miss Davydova. She had scored a 10 in the event in the earlier team competition but gave a weaker performance this time. Miss Simionescu started a long dispute by refusing to accept Comaneci’s mark from the four-referee panel”.

( A better comparison would have been Nadia’s 9.9 in team optionals since the optional routine is what is competed in the AA, not compulsory. Compulsories are less difficult and Nadia’s compulsory 10 routine would have been worth at most a lowly 8.4 were it allowed to be competed as an optional exercise.)

C.Robert Paul jr, first sports information Director and Director communications for the United States Olympic Committee, United States Olympic book 1980, p.140-141,wrote on Comanecis beam routine “She was good but not great”.(On Davydova), ”There was never a doubt about her all-around abilities. Simply stated, however, it was expected that judges, by their very nature, might favour the better known and more established international stars…But the order of finish Davydova, Gnauck and Comaneci (tie), Shaposhnikova and Kim certainly accurately reflects the relative abilities of the worlds top gymnasts”

Gym Stars, june/july/august 2000, page 4,” Nadia was on beam and needed 9.95 to beat Elena. Nadia had a small wobble and a step on her dismount so things were looking good for Elena”.

Fred Rothenberg, AP sports reporter, Moscow, p.13, july 25 1980, Gettysburg Times, ”Her routine on the beam wasn’t vintage Comaneci. It wasn’t perfect. She wobbled a bit on one manouver then she stumbled a little on her dismount”.

Even the Romanian TV commentator Cristian Topescu, commentating live on Romanian TV, accepted it wasn’t perfect “She lost her rhythm in the middle of the exercise and we should try to see if this will bring her score down”.

Karen Inskip-Hayward, ”The Golden Decade : women’s gymnastics in the 1980’s”, 2007, p.17, ”Surely the score should be easy to calculate ? With a 0.1 deduction for the wobble and 0.1 for the step 9.80 should be her maximum score. She needed 9.95 to win outright, which would mean some judges giving her a perfect score for an obviously imperfect routine. The result seemed obvious”.

Randy Harvey, LA Times, August 2 1984, H.24 , ”From the look of her face following the performance it was apparent that Comaneci did not feel she had earned the score she needed to win”. Nadia had performed a better beam exercise in team optionals and scored 9.9 so it is difficult to see how a poorer routine could score higher.

Alena Prorokova the Czech judge involved, recalling the events in 2007, wrote “But I am well aware that Comaneci ended her routine on the beam with the element B+C. This final score she received because she did a jump at the end of her routine in which instead of pushing off from both feet at the same time, she jumped by pushing off from one and then the other, and that is why she received a lower score of B+C instead of C+C. I am convinced that the score given was fair and correct”.

Prorokova officiated at more than 140 competitions including the World Championships in 1962 66 and 78 and the Olympic Games in Tokyo, Mexico, Munich and Moscow. Of the 4 judges on beam she was the most experienced. Her husband, Vladimir Prorok, was the coach of the legendary Czech gymnasts Vera Caslavska and Eva Bosakova. Both Alena and Vladimir worked in West Germany from 1981-87 and were the coaches of the West Gernman national team at the L.A.Olympics where the team finished 4th.

Peter Shilston British Gymnast magazine, September 80, p.24, ”Finally, Comaneci was rightly given only 9.85”.

The largest Italian sports newspaper, Gazetto dello Sport, noted “In fact her correct rating was exactly 9.85”.

The controversy began when no score was registered on the scoreboard. For 28 minutes gymnastics stole the show from all other sports and even advertisements on western television stations were delayed. In the arena a British journalist lighted up a cigarette to calm his nerves. Although smoking was prohibited no one noticed amidst all the drama.

Deductions were taken in tenths by the judges i.e. 0 if the judge thought the exercise was perfect, 0.1 0.2 0.3 etc depending on how many errors the judge noted. The marks were 10 from the Bulgarian judge, 9.9 from the Czech judge and 9.8 from both the Soviet and Polish judges (3 of the 4 judges didn’t believe her beam exercise was good enough to win gold). Simionescu, knowing that Nadia needed 9.95 to win gold refused to post this score causing the delay.

Ioan Chirila Nadia (2002) “The Romanian Gymnastics Federation studied which referees had so-called “weaknesses” which could be exploited to Romania’s advantage”. To be gifted extra tenths. Is this what happened here? The odd score out is actually the Bulgarian judges 10. Her score is out of consensus with the other members of the panel. Her score’s distance is 3 times greater from the median score – 9.85- than any of the other judges – 2 were 0.05 below, 1 was 0.05 above. Is it reasonable to give a perfect score to a routine with such an imperfection? Bart Connor commentating on Seoul Olympics uneven bars event final on Dagmar Kersten’s routine, “I’m sorry but if you take a step on landing the judges shouldn’t be able to throw you a 10”. After the 1990 World Cup Nellie Kim was suspended as a judge, for, among other things, scoring a gymnast who took an obvious step on landing a 10.

Bela Karolyi, the Romanian team coach,was peering over the shoulder of the Head Judge on beam – Maria Simionescu, a fellow Romanian – observing the scoring judge’s marks and when he saw that Nadia wasn’t going to win he started remonstrating and shouting at the judges.He tried to mug his way to the medal by intimidating the judges. Nadia said Bela spat at the judges and he himself boasts that twice he knocked over the scoreboards. Ernest Hemingway wrote that one of the virtues of sport was that it taught people how to lose with dignity.Unfortunately it didn’t happen in this case.

(Bill Sands wrote more than 10 books on gymnastics and coached 7 US national teams including the 1979 World Championship team, Director research and development women’s program USA Gymnastics and was the vice-chair for research for the US Elite Coaches Association for women’s gymnastics, explained the rules under which a gymnasts score could be inquired into in his book “Everybodys Gymnastics Book, 1984, p.59, ”The protest cannot be a comparative analysis of the scores. It must refer to specific occurrences in the routine of the gymnast in question and must always be made with the upmost respect. In other words, the protest cannot simply be a character assassination directed at the judges”.

British Gymnast, April 80, p.13, “ It is tempting to compare your own gymnast’s mark with that of another gymnast or even her own mark at a different competition. That again is incorrect procedure”).

One US sports editor wrote “There was even a candidate for best actor in the person of Romanian coach Bela Karolyi who earned automatic life membership in the Illie Nastase school of histrionics with his raging, seething,hands on head performance”. Washington Post noted “At various times, he stomped his foot, waved his arms, charged the jury, and shrieked at the Soviet judge whose nose was no more than two inches from Karolyi’s mouth”

Davydova has won the AA gold. Who stands to benefit from any delay ? Who gets hurt most by the delay in posting the score ?

Madame Simionescu violated her Olympic oath by not posting the score. She had been the Romanian women’s gymnastics team coach at the 1956 60, 64 Olympics. In 1969 she established the gymnastics school where Nadia trained. The first time Nadia’s name was mentioned in the Romanian press was in May 1971, by Maria Simionescu. Daily Mirror, April 17, 1978, p.23 Frank Taylor, ”Maria Simionescu, the woman who was largely responsible for the development of Nadia Comaneci and Teodora Ungureanu and the Romanian gymnastics school”. Nadia herself wrote in “Letters To A Young Gymnast”, P.24, “ The Onesti gymnastics school originally designed and created by a family named Simionescu. Its hard to express in words my thanks to the Simionescus for bringing to life such an incredible program, to which I owe much of my success”. Simionescu had been a friend of Nadia’s since Nadia’s childhood and had given her ballet training. When Nadia was ill she recuperated by staying in Simionescu’s apartment. She had travelled with the Romanian team numerous times and socialised with them. She would intervene again in beam event final to restrict the score of Shaposhnikova which would give Comaneci beam gold. Nadia repeated her score of 9.85 here.

As an act of bad sportsmanship Simionescu’s actions in the AA final were like the boxer at the Seoul Olympics who protested the result of his fight by staying in the ring for 67 minutes thus delaying the competition.

Peter Shilston wrote in October issue of IG, p.11, ”Easily the weirdest moment was the judging dispute over Comaneci’s beam which was shown live, all 30 minutes of it, with Madame Simionescu and Frau Berger apparently in heated debate and Karolyi striding in like a bar room brawler. Midway through this nonsense, an enterprising cameraman managed to zoom in on the judges score sheets and Barbara Slater was called in to decipher the hieroglyphics for the viewers. She’s been given 9.85 was the prompt answer – and so of course she had, but it took another 10 minutes to finalise it”.

Hardy Fink,”The dangers of subjectivity”, Gymnastics Guide, 1978, p.292, ”Ego involvement with the gymnast may occur if the judge knows the gymnast well”. They develop an affinity for those girls in whom they’ve invested.

Barbara Slater commenting on TV “(Crowd) The Romanians chanting trying to influence the judges… It seems really strange that the Romanian judge there should have such an important role to play in deciding whether Comaneci or not should win the gold medal…(on Simionescu’s behaviour) This really is a tragedy. We’re seeing politics come into play”.

IG, October 1980, Greek reporter Zacharias Nikolaides, ”Simionescu refused to write the score on the electronic scoreboard and then came Ellen Berger, chief of the women’s technical committee, who said that Simionescu was obligated to write the score”.

Irish Press, July 25 1980, p.16, “ The judges who were not directly involved in the Comaneci decision said afterwards that the row broke out after Mrs. Simionescu refused to enter the marks awarded to the defending champion because it meant she would not have won the gold medal. The judges, however, refused to change the marks”.

The score was eventually posted. The other Soviet gymnasts aided by Katherina Rensch of East Germany and Lena Adomat of Sweden tossed Elena in the air in celebration.

IG magazine, September 1980, p.29, Lyn Moran – IG associate editor, America’s first woman international sportswriter and author of the book “The Young Gymnasts” – wrote “Elena Davydova whose sparkling performances drew raves from everyone who saw her in action…has been around the gymnastics scene for seven years. Davydova received a perfect score for her brilliant floor artistry…her floor routine was one of the most exquisite and delightful performances I have ever seen. Her tumbling was exceptionally good but it was the dance which literally captivated everyone. In a phone conversation with our Greek correspondent Zacharias Nikolaides, he said that he and a group of Greek judges watched the whole competition on television from the very first day to the very last, and that all had agreed that Yelena’s fx was brilliant (deserved more than a 10.0 was how he put it ! ). Nikolaides said that each routine was replayed in slow motion and that all the way through he and the Greek judges acted as scorers to see how their scores compared to those given in Moscow. The following are his comments :

“Davydova was, well, just breathtaking. All of us thought that Nadia was overscored on her beam routine which brought her a 10.0. That was too high. As far as the controversial score of 9.85 went, however, we are all in absolute agreement with the judges. We saw it in slow motion and replayed more than five times. The judges with me made their determination according to the rules, and they all came up with the same score of 9.85. I also agree with them that the behaviour of Bela Karolyi is a disgrace. Nadia’s scores were very fair indeed; overly so. None of us saw anything wrong with the judging. The coverage was in such great detail that we saw everything over and over from the first routine. We think the judging was correct based on what our own judges saw.” Nikolaides talked to their Greek reporter in Moscow who concurred with the judge’s decision on Nadia.

The controversy arose when there was a dispute between the Head Judge, Maria Simionescu (a Romanian) and the Head Judge of the women’s technical committee, Ellen Berger of the GDR, who is over all the judges. There are no Russians at all on the FIG gymnastics committee for women. The 4 judges from 4 different countries gave their score, which was questioned by the Head Judge, from Romania, who thought it should have been higher. Mrs.Berger was brought in to arbitrate and she said the 9.85 score should stand and this was based on the two median scores, after dropping the high and the low. Unfortunately, the media seized upon this dissension to rap the USSR judges although only one of the six judges in question was actually Russian, and although few of the reporters knew how international scores were arrived at. Nadia looked good on some events and not on others”.

Frank L.Bare, first executive director of the US gymnastics federation, served in that capacity through 1979. He also served as vice-president and member of the executive committee of the International Gymnastics Federation (FIG). He edited “The Complete Gymnastics Book” published in 1980 and on p.95 he wrote “a scandal developed concerning the awarding of a score for Nadia Comaneci of Romania. The Superior Judge for the event was a Romanian and she absolutely refused to flash the score because she felt it was too low. The influence of having a Superior Judge on the floor during a competition is tremendous. Had the Romanian judge being in the stands the score simply would have been flashed and the meet would have continued but, as it developed, the delay was for 30 minutes while the debate went on about the score”.

Jack Broughton, columnist for the British gymnast magazine “The Gymnast”, February 81, p.7, ”The Romanians need to polish up their international image, particularly after the unseemly conduct of their officials at the Moscow Olympics last year”.

Peter Aykroyd, writer of over half a dozen books on gymnastics and editor of ”The Gymnast”, wrote July 81, p.3, ”We can now hope for the end of unseemly scenes such as that witnessed by millions on television when the Romanian Master Judge delayed the score of her fellow Romanian Nadia Comaneci”.

Ursel Baer, a British judge who set the start values on beam at the 1980 Olympics,“On the beam there was a controversy about the marks given to Comaneci, sparked off because there was a Romanian Head Judge”.

Tom Ecker served as national coach for Sweden in the 1968 Olympics and represented the USA on technical committees prior to the 1980 and 84 Olympics. He was selected to deliver lectures at the Olympics during the 1968 72, 76 Games and he taught courses on the Olympics for California State University in 84 88, 96. He was the only American presenter at the International Coaches Association meetings at the Olympic Academy in Olympia, Greece, in 1986. In 1996 he wrote the book “Olympic Facts and Fables”. On page 127 he wrote under the heading “Another Judging Bias” the following; ”Nadia Comaneci of Romania, the darling of the Olympic gymnastic competition in Montreal, was back to defend the titles she had won in 1976. However, she suffered a fall during her uneven parallel bars performance and needed a nearly perfect score of 9.95 on the balance beam to win the gold medal. She scored only 9.85, but the chief judge, who was also Romanian, argued that the score should have been 9.95 and refused to ratify the lower score. After a 25-minute argument with the other officials, the Romanian judge gave in and Comaneci received the silver medal”.

Australian judge Jeff Cheales, who judged at the 1979 World Championships and 1980, 1984 and 196 Olympics and also conducted judging courses for the F.I.G., commented “Tom Ecker’s book aimed squarely at Simionescu without actually calling her a cheat. The heading said that for him”.

Glenn Sundby was the founder and editor of the International Gymnast magazine (IG). He was also a founder member of the United States Gymnastics Federation (USGF), its first Vice-President, founder of the International Gymnastics Hall of Fame (IGHOF) and of gymnastics’ first World Cup. In the September 1980 issue, p.6, he replied to errors in letters from readers on the judging at the Olympics.

“Oops – you erred ! It was not Ellen Berger who altered any scoring but the Romanian Head Judge who asked the 4 different judges to up their 9.85 score. Nadia’s beam was not downgraded. This misconception is really unfair to the judges concerned. We hope the FIG scoring system will make you realise nothing was biased, unless Simionescu’s intervention is seen that way.

As Madame Berger relates it and she is well respected and very reputable and not known to lie, the median scores of the 4 judges was 9.85, after the top and bottom score was dropped, as is customary. However the ROMANIAN Head Judge, Maria Simionescu, refused to accept this 9.85 verdict, so the 4 judges called in the head of the women’s technical committee, Ellen Berger, to arbitrate. Please note that there are no Russians represented in women’s committees in the FIG at all !

Madame Berger concurred with the 9.85 and that unless there is more than a 1/10th discrepancy between the median scores (per the FIG rules) this score should stand. President Titov came down to find out why six women could not agree on a simple score. The independent Greek reporters and judges also agreed with that score. Everything points to the bias being with the Romanians, NOT the Russians.

Davydova would have won anywhere on this earth with that floor exercise”.

John Goodbody began reporting on gymnastics in 1968. He covered Olympics, Worlds and European gymnastics for various British newspapers, UPI and BBC radio. He has covered 11 summer Olympic Games starting in 1968. He was sports correspondent for The Times newspaper for nearly 22 years winning journalistic awards in every decade with the paper, being voted sports reporter of the year in 2001 and getting the prize in 2002 for the sports story of the year. In 1982 his book “The Illustrated History of Gymnastics” was published. Pages 82 to 97 cover the 1980 Olympics and competitors there. ” Davydova’s striking routine of verve and versatility gave her a maximum 10…Her willingness to take risks gave her a margin of supremacy…It was amazingly close with Davydova owing her victory to her consistency…(Nadia) Her routine lacked it’s usual composed precision. She swayed unmistakably on the beam and her dismount was slightly askew…Mrs Simionescu could not persuade the judges to alter their scores and eventually Mrs Berger entered the dispute. She supported the judges, telling me the next day that, in her opinion, Comaneci’s performance was worth 9.85 points…The necessity of restoring calm to a fraught situation may explain what occurred the next night. On the beam, where the same judges were officiating as on the previous evening, there was a dispute over the marking of the Soviet Union’s Natalia Shaposhnikova. This time, it appeared, Mrs Simionescu succeeded in restricting the mark to 9.85 points, which gave Comaneci her first gold medal of the tournament…It was scarcely surprising that Franklyn Edwards, President of the BAGA, was eager for the FIG to scrutinise the incidents to prevent any repetition. Edwards suggests that no coaches should be allowed to talk to officials and the Head Judge should be, if possible, from a neutral country”.

The Complete Book Of The Olympics 2012 edition, David Wallechinsky and Jaime Loucky, p. 784, “ the contest for All-Around Champion came down to the final apparatus. Performing fourth for the Soviet team, the 18 year old Davydova was not expected to qualify for any final events, and at best was thought to be in the running for the All-Around bronze medal. In the final rotation, Maxi Gnauck was second among the nine gymnasts on the vault, but lost the lead after scoring only 9.70. Performing seventh on the bars, Davydova delivered a bold, confident routine. Her score 9.95, put her in first place and gave her a lead that only Comaneci could hope to overtake, and then only if she also scored 9.95 on her final beam routine. The last time Comaneci had scored that high on the beam in an All-Around final was at the 1976 Olympics. Her average score was closer to 9.75.

With the arena in complete silence, Nadia went through an impressive routine with only two small errors, including a step back on landing. The 1980 US Olympic book described the routine as “ good, but not great”. The real controversy, however, began when the scores were being tallied. The Romanian head judge, Maria Simionescu, a friend of Comaneci’s since 1969, refused to accept the final result and tried to get three other judges to increase their scores. The judges argued for 28 minutes before overruling Simionescu’s complaint. Even then she refused to punch the score into the computer. A representative of the Moscow Organising Committee had to do it while Simionescu looked on in rage. Finally Nadia’s score flashed on the computer : 9.85. Davydova had won the gold medal”.

In their book, The Book Of Olympic Lists, 2012, p.96, Wallechinsky and Loucky give the same account under the heading A Disgruntled Judge.

David Wallechinsky is President of the Society of Olympic Historians.

(Only 3 members from any one team could qualify to the AA final and a maximum of 2 to an event final. In the team competition – whose scores counted towards both AA medals and event finals – Davydova was hampered by performing 4th for her team before Kim and Shaposhnikova. Comaneci and Gnauck performed 6th for their respective teams.To Davydova it was like beginning an 800 metre race 60 metres behind the starting line.Essentially – because of the well-known and well-established staircase effect – they had a head start over Davydova in the scoring and she would have to perform better than them to achieve the same score. Davydova knew from her position on the team that her role was to back up Shaposhnikova and Kim who were the Soviet team selector’s 2 favourites to reach event finals and AA final).

David Miller, The Official History Of The Olympic Games And The IOC, Athens To London 1894 – 2012, p.235, “When it came to the final apparatus for the all-around individual title, there was all to play for between Gnauck, Comaneci and Yelena Davydova ( URS). The aura of tension in the Lenin Sports Palace was such that you could have heard a mouse sneeze. On the final rotation, Gnauck was performing second among nine gymnasts on the vault, Davydova seventh on the bars and Comaneci eighth on the beam…Gnauck’s chance evapourated with poor vaulting. Davydova, whose artistry had been brilliant in the floor exercise, performed confidently on bars scoring 9.95 and take the lead. Now Comaneci needed the same score on the beam. Her average on the beam had recently been 9.75. Her performance was sound but not exceptional, for a score of 9.85. Davydova had won the gold but no score appeared on the board and for half-an-hour the crowd, and performers, remained in suspense as the judges argued. Maria Simionescu, the chief judge and a Romanian who had known Comaneci for more than ten years, was refusing to ratify the amalgamated mark of 9.85″

Simionescu was unable to discard national prejudice.She had “one eye” and it was always focused on improving the scores of her Romanians. Her rating of Comaneci’s routines was manipulated and prompted by false patriotism.

At the 59th FIG General Assembly there was criticism of some of the judges at the 1980 Olympics.But the only Head Judge criticised – in either the men’s or women’s competition – was Simionescu.(FIG Bulletin, no 110, 1981, p.70).

To paraphrase a poem by Ogden Nash :

“There once was a judge whose vision,

was cause for abuse and derision.

She replied in surprise

Why pick on my eyes,

It’s my heart that dictates my decision”.

Another wag wrote that the Romanian behaviour at the 1980 Olympics showed that it wasn’t only the vampires in Transylvania who are allergic to silver.

In 1984, before the L.A. Olympics, the United States Gymnastics Federation proposed to F.I.G “When the average score of a gymnast is 9.8 or above, the superior judge should not be permitted to have discussion with any of the other judges concerning the final score.

Reason : To eliminate the possibility of the superior judge alone affecting the final placement or rank of the gymnast”.

( FIG Bulletin, no.121, 1984, p.91).

Bill Sands wrote about the dangers “The Superior Judge might try to force the opinions of the judges toward his or her way of thinking by intimidation and thereby influence the direction of the scoring and winners”.

In relation to Simionescu IG noted in 1982 that whenever the Romanians were involved in controversy Simionescu was always there. She was a lightning rod for controversy.

Lyn Moran, IG, March 1982, p.75, ”Mdme.Simionescu has been a friend of Nadia’s since her childhood, and she has travelled with the Romanian team countless times. They have socialized together, gone to movies together. The times when the Romanian team became embroiled in scoring controversy indicate that Maria Simionescu was always present. In fact, at the big Moscow confrontation over Nadia’s 9.85 beam routine the Head Judge, and first Vice President of the Women’s Technical Committee, was (once again) Mdme.Simionescu. Nadia says herself that she had 2 definite breaks and that mentally she had scored herself at 9.80. The Romanian Head Judge, according to Nadia, flatly refused to put up the score, telling the FIG Committee President to put it up herself.

Well, if this were any other international sport we would by now have resolved these perennial scoring conflicts, and the first thing would be to isolate all judges from all gymnasts at all times just as in pro sports. No judge can be truly impartial when they have a subjective, personal involvement with any performer”.

The final point is the body shaming comment about Davydova in Sports Illustrated .From 1980-2024 the avaerage height and weight of the women’s AA winner at the Olympics was 1.48 m tall and weight 43.4 kg. Average BMI was 19.63. Davydova was 1.48 m tall, weighed 45 kg and her BMI was 20.5.