Moscow, November 1981. A young gymnast takes her starting position at Luzhniki Sports Palace. When the opening notes of Rossini’s La Cenerentola (Cinderella) sound through the arena, fifteen-year-old Natalia Ilienko—so says her official biography—begins what Soviet journalists will soon call a “sparkling” performance, an “étude set to Rossini, in a minuet-gavotte style.”

The routine, choreographed by Natalia Alexandrovna Marakova, is “elegant, polished down to the smallest detail—to every movement of the flexible hands, to each glance—now languid, now playful.” When Ilienko completes her final tumbling pass, the crowd erupts. Moments later, she will stand on the podium as the floor world champion, one of her country’s newest gymnastics sensations.

But there was a problem with this triumph: Natalia Ilienko should never have competed at those World Championships.

She was too young.

The Numbers Don’t Add Up

The minimum age for World Championships competition in 1981 was fifteen years old. According to her official competitive biography, Natalia Ilienko was born on March 26, 1966, making her fifteen years and seven months old when she competed in Moscow in November 1981.

But a 2020 biographical reference book published in Chelyabinsk, Russia—Guests of the Chelyabinsk Region, 1900–2000—tells a different story. According to this meticulously compiled volume, Natalia Nikitichna Ilienko was born on March 26, 1967.

Not 1966.

That single digit changes everything. She was fourteen years and seven months old when she competed at the 1981 World Championships. One year too young.

The Traces in the Archives

The documentary trail reveals when the falsification seems to have begun. It happened well before the world was watching in 1981.

In October 1979, Sovetsky Sport reported on the Druzhba tournament in Minsk, where “12-year-old N. Ilienko from Alma-Ata” dazzled spectators with her floor routine to Mozart. The reporter described her as “an astonishingly gifted, very supple gymnast with excellent schooling and technique.” Her composition included two double somersaults and a double twist, “softened by the expressiveness and artistry of the young athlete.”

Twelve years old in 1979. Born in 1967. The age was correct.

But something changed between October 1979 and April 1980. By the time of the USSR Championships in Kyiv—a crucial selection competition for the home Olympics—Ilienko’s age had been quietly adjusted. She was now listed as fourteen years old.

The April 25, 1980, report in Sovetsky Sport captured her prowess at those national championships. Olympic champion Larisa Petrik, offering commentary on the floor exercise final, singled out “14-year-old Natasha Ilienko for her plasticity and lyricism,” noting that had Natasha not fallen on her double salto dismount, “she would have been among the medalists.”

The timing does not seem to be coincidental. Fourteen was the minimum age for Olympic eligibility in 1980. If Ilienko remained thirteen—her true age—she couldn’t be considered for the Moscow Olympics. Someone made a decision: add a year.

And that’s how Ilienko skipped turning thirteen, jumping from twelve to fourteen—at least on paper.

The Rising Star

While numbers were manipulated behind the scenes, the gymnast herself was simply doing what she did best: training, competing, and captivating audiences with her artistry.

By 1981, Ilienko had become impossible to ignore. At the Moscow News Tournament in March, she took second in the all-around after a hand-slip on her uneven bars mount cost her the title. But on balance beam, she was “wonderfully good,” her movements flowing “capriciously, colored with a femininity of—let’s say—an Astakhova shade.” Sovetsky Sport‘s Vladimir Golubev and Stanislav Tokarev wrote that Ilienko possessed “not merely plastic skills, but a special inner musicality.”

In April 1981, Olympic champion Olga Kovalenko (Karasyova, née Kharlova) interviewed the young gymnast for the sports press. The piece, titled “Time to Learn!”, painted an intimate portrait. Kovalenko described watching Ilienko prepare for her beam routine, knowing the “energy which has been building up and waiting for its moment” would soon “burst outward.”

What followed was a performance that left the veteran champion in awe. Ilienko executed “a backward salto on the beam” immediately after “a wide, high leap”—a connection “that no gymnast in the world has yet managed.” The routine finished with a double salto dismount, performed “so gracefully and deftly, as if it cost her no effort at all.”

In their conversation afterward, Ilienko came across as earnest and hardworking. When asked what she was thinking before her routine, she simply said, “Only that I should do everything the way I do in training: not better and not worse, just the way I can.” Asked if she got tired from all the training, she smiled: “No, I train in the gym with pleasure, and the tiredness is pleasant.”

Her near-term dream? “I want to perform successfully at the country’s winter championship in Leningrad and make the team for the May European Championships among adults.”

“A talented girl, our hope,” Kovalenko concluded. “She has natural artistry, femininity, softness”—characteristics that few gymnasts possess, regardless of their age.

Moscow, 1981

By the time the World Championships came to Moscow in November 1981, Natalia Ilienko’s falsified age had been part of the official record for over a year and a half. Unlike Bicherova’s age, few questioned it. Though, the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung noticed: “That in at least two cases (Natalia Ilienko and Olga Bicherova) the birth years officially stated on earlier occasions were backdated by one year (from 1967 to 1966) is a fact.”

Despite the age controversy, the championships were a showcase for Soviet gymnastics, and Ilienko delivered. Her floor exercise—that Rossini étude with its minuet-gavotte styling—earned her a gold medal. The December 1, 1981 edition of Sovetsky Sport celebrated her triumph among the “unforgettable moments of the World Championships,” noting that “Natalia Ilienko amazed spectators with her sparkling floor exercise. A gold medal for the schoolgirl from Alma-Ata!”

The reporters praised the choreography, the elegance, and the artistry polished “down to the smallest detail—to every movement of her flexible hands, to each glance—now languid, now playful.” They compared her innovative choreographic approach to that of Elena Davydova and Bulgarian Zoya Grancharova, suggesting that “many ideas were likely borrowed from rhythmic gymnasts.”

It was a coronation. A new star had arrived.

The Lie Becomes Harder to Maintain

Age falsification has a weakness: maintaining the falsehood requires the participation and vigilance of multiple parties, and vigilance often fails.

By 1984, Natalia Ilienko had established herself as one of the Soviet Union’s top gymnasts. In April of that year, she traveled to Donetsk for the 50th USSR Championships—a jubilee competition that would determine the country’s national champion.

The April 20, 1984 edition of Kazakhstanskaya Pravda described the dramatic finish: “The gymnasts’ competitions at the jubilee 50th USSR Championship in Donetsk unfolded with extreme sporting intensity and emotional tension. Quite literally until the final rotation, it was impossible to determine who would become the country’s all-around champion.”

Three gymnasts were in contention: Olga Mostepanova of Moscow, who “performed inspiredly at the start of the tournament”; Irina Baraksanova, “a young schoolgirl from Tashkent who continues to amaze specialists with the maturity of her skill well beyond her years”; and the third contender, “17-year-old tenth-grader from Alma-Ata, Natalia Ilienko.”

Mostepanova led from the first rotation. Ilienko was in third, trailing Baraksanova by one-tenth. “But closer to the end of the competition, Natalia managed to show her character and ultimately posted the best all-around total—77.15 points.” Mostepanova finished 0.25 points behind; Baraksanova 0.325 points behind.

Seventeen years old, the article said.

But according to the falsified birthdate that had been in place since 1980—March 26, 1966—Ilienko should have been eighteen years old in April 1984, not seventeen.

The newspaper had printed her real age, using her real birth year: 1967.

It’s revealing that this slip occurred in Kazakhstan’s own press. Perhaps local journalists knew her actual birth year. Perhaps they were simply less careful about maintaining a fiction that had been manufactured in Moscow. Or perhaps, after four years, the cognitive burden of remembering which age was “official” and which was real had simply become too much.

The article went on to note that Ilienko was now “considered one of the main contenders for a place on the core lineup of the USSR Olympic team,” training intensively for the Los Angeles Olympics under the guidance of coaches Natalia and Yuri Tsapenko, and choreographer Natalia Marakova.

Four months later, in August 1984, Sovetsky Sport prepared a preview of the Friendship-84 tournament—the Soviet bloc’s answer to the Olympics they were boycotting. The article described the Soviet women’s team, noting that “18-year-old Natalia Ilienko of Alma-Ata” would compete.

Eighteen—the age she should have been according to the fiction of her competitive age.

The inconsistency reveals how easily the deception could unravel. One paper said seventeen. Another said eighteen.

Both couldn’t be right.

But one was true.

References

Primary Sources

Sovetsky Sport, October 16, 1979 (No. 239). “MINSK.” Report on the Druzhba tournament. Lists “12-year-old N. Ilienko from Alma-Ata.”

Sovetsky Sport, April 25, 1980 (No. 96). G. Borisov and V. Golubev, “There Is Work to Be Done.” Report on the USSR Championships in Kyiv. Olympic champion Larisa Petrik comments: “I liked the 14-year-old Natasha Ilienko for her plasticity and lyricism.”

Sovetsky Sport, March 31, 1981 (No. 75). V. Golubev and S. Tokarev, “Spring Voices.” Report on the Moscow News Tournament. Lists “the fifteen-year-old Alma-Ata gymnast Natasha Ilienko.”

Sovetsky Sport, April 7, 1981 (No. 81). O. Kovalenko, “Time to Learn!” Profile of Ilienko. Opening line: “Natalia Ilienko, 15 years old.” Describes her as “a delicate fifteen-year-old girl.”

Neue Zürcher Zeitung, November 26, 1981 (no. 275). “Dubious Practices.”

Sovetsky Sport, December 1, 1981 (No. 277). Report on the World Championships in Moscow. “Natalia Ilienko amazed spectators with her sparkling floor exercise. A gold medal for the schoolgirl from Alma-Ata!”

Kazakhstanskaya Pravda, April 20, 1984 (No. 97). A. Nikolenko, “Natalia Ilienko — Absolute Champion of the USSR.” Reports on the 50th USSR Championship in Donetsk. Describes Ilienko as “17-year-old tenth-grader from Alma-Ata.”

Sovetsky Sport, August 16, 1984 (No. 188). G. Vladimirov, “All the ‘Stars’ of the Gymnastics Podium.” Preview of Friendship-84 tournament. Describes Ilienko as “18-year-old Natalia Ilienko of Alma-Ata.”

Biographical References

Stoyakin, I.V., and V.B. Ferkel, eds. Guests of the Chelyabinsk Region 1900–2000: Biographical Reference Book. Vol. 2. Chelyabinsk, 2020. Entry for “Ilienko, Natalia Nikitichna” lists birthdate as March 26, 1967.

Gymn-Forum. “Natalia Ilienko.” Biographical entry. Available at https://www.gymn-forum.net/bios/women/ilienko.html. Lists birthdate as March 26, 1967.

Note: The discrepancy between reported competition ages in Sovetsky Sport (12 years old in October 1979, 14 years old by April 1980, 15 years old by March 1981) and the documented birth year of 1967 in multiple biographical sources reveals age falsification that made Ilienko appear one year older than her actual age, allowing her to compete at the 1981 World Championships when she was 14 years old—one year below the minimum age requirement of 15.

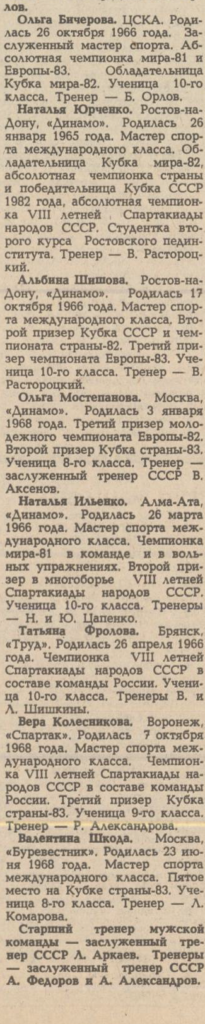

Olga Bicherova: October 26, 1966

Natalia Yurchenko: January 26, 1965

Albina Shishova: October 17, 1966

Olga Mostepanova: January 3, 1968

Natalia Ilienko: March 26, 1966

Tatiana Frolova: April 26, 1966

Vera Kolesnikova: October 7, 1968

Valentina Shkoda: June 23, 1968

Appendix A: The Full 1981 Profile of Ilienko

Time to Learn!

Athlete Profile. Natalia Ilienko, 15 years old. “Dynamo,” Alma-Ata. Seventh-grade student. 1980 USSR champion on uneven bars, winner of the international gymnastics tournament for the prize of the newspaper Moscow News on balance beam. Coach — N. Popova.

…Here she stands, a delicate fifteen-year-old girl. Why does Natalia Ilienko—she in particular—make one think, why does one want to learn more about her? Sometimes it’s hard to explain our own desires. After all, we don’t ask ourselves why we love flowers…

Natasha prepares to perform on the balance beam. Her face seems calm. But what must be going on in her soul! Oh, I know this feeling very well myself. In just a few seconds, Natasha will begin her routine, and that energy, which has been building up and waiting for its moment, will burst outward. Has this schoolgirl from Alma-Ata managed not only to teach her body to perform unbelievable movements in the air, but also to tame her own “self,” to suppress her nervousness and channel it in such a way that it helps her be more focused and gives her only inspiration?

A short run, a take-off—and the gymnast is already executing her routine. The movements are light and unforced. Natasha seems to be floating above the apparatus, barely touching it. “Ah!”—the hall reacts in delight and in a single breath to a difficult element performed successfully. Yes, a fine idea from the gymnast and her coach, Natalia Popova. A backward salto on the beam is not new—Olga Korbut conquered audiences with it twelve years ago. But to perform a “Korbut salto” immediately after a wide, high leap—that no gymnast in the world has yet managed!

Well, the rules of judging provide for rewarding originality, and Ilienko has already earned precious tenths of a point for the original connection. And I, as a judge, make notes for myself in the score sheet.

The sports palace grows quiet again in anxious anticipation: Natasha performs a cascade of acrobatic elements and finishes her routine with a double salto dismount! Not every gymnast would dare such a risky ending, and Ilienko executed it so gracefully and deftly, as if it cost her no effort at all.

— Natasha, are you satisfied with your result?

Instead of an answer, I see a surprised look and realize that she is not used to seeing a judge in the role of a correspondent. Then she smiles, and a candid conversation begins between us.

— Yes, of course. Last year I also performed at this competition, but out of the contest and not so successfully. What was I thinking about while preparing for my beam routine? Only that I should do everything the way I do in training: not better and not worse, just the way I can.

— I know you train a great deal. Don’t you get tired?

— No, — Natasha answers, — I train in the gym with pleasure, and the tiredness is pleasant.

— Who impressed you at this tournament?

— Yuri Korolyov! He performed well, and he has a kind character.

— Near-term dreams?

— I want to perform successfully at the country’s winter championship in Leningrad and make the team for the May European Championships among adults; I’ve already been to the junior event.

I wish my interlocutor success. We say goodbye, but thoughts of her don’t leave me. A talented girl, our hope. She has natural artistry, femininity, and softness. She gets enormous satisfaction from gymnastics. But life isn’t so simple; she will need the ability to work, persistence in achieving her goals, and strength of character. I believe that together with her coach, Natalia Popova, who earlier trained the charming Olga Koval, Ilienko will reach Olympic heights.

Go for it, Natasha Ilienko—now is your time to learn from great gymnasts: Nelli Kim, Elena Davydova, Natalia Shaposhnikova. But in learning, strive for perfection, strive to surpass your teachers!

— O. Kovalenko, Honored Master of Sport.

Sovetsky Sport, April 7, 1981

Appendix B: Sovetsky Sport on Ilienko’s 1984 All-Around Title

NO ROOM FOR ERROR

Alma-Ata schoolgirl Natalia Ilienko received the gold medal of the country’s all-around champion for the first time

…She is graceful and lyrical, her gymnastics is built on fine lines, poetry, and elegance. Even complex elements that require strength or sharpness in their execution take on soft contours in her routines…

Previously, Natasha Ilienko was let down by a lack of consistency. Specialists sometimes threw up their hands: “With such weak tumbling and simple vaults, it’s hard to count on a place on the national team.” Yes, it wasn’t easy for Natasha. And it was even more hurtful for coach Natalia Konstantinovna Popova-Tsapenko to hear this, who has always been together with her student for ten years.

I asked Popova many times what qualities she values in Natasha, and every time I received the same answer: “Extraordinary work ethic and a sharp mind.”

Watching Ilienko in training, I was amazed by her tirelessness. But Natasha is like this not only in the gym, but also at school. She is finishing tenth grade, and by the way, is a contender for a gold academic medal.

Ilienko is a two-time world team champion and the 1981 world champion on floor exercise.

Natasha stood out on the floor in Donetsk as well, but to receive high scores, she had to increase the difficulty of her second tumbling pass. And in general, compared to last year’s world championship, where Natasha did not win any individual medals, she updated her routines on three events.

At last year’s USSR Spartakiad, Ilienko was second behind Natasha Yurchenko. Now she reached a new summit.

…Recall that before the final, Muscovite Olga Mostepanova was in the lead. Elena Shushunova, Vera Kolesnikova, and Tatiana Frolova could have contended for championship medals. But they went to an international tournament (together with Angela Shchennikova, who was in eleventh place). Thus, the main competition was between Mostepanova, Ilienko, and 15-year-old Ira Baraksanova from Tashkent.

On vault, Baraksanova received a 10.05 (according to our rules, the “Yurchenko vault” with a full twist is valued at 10.2 points). For a “Tsukahara” with a full twist, the judges gave Mostepanova 9.9. The gap between Olya and Ira narrowed to a minimum.

On uneven bars, Ilienko easily flitted from bar to bar and afterwards even smiled—an extreme rarity for her in competitions—when she saw her score: 9.7. The other gymnasts, for some reason, faltered. World champion Olya Bicherova made a mistake—only 8.85, Mostepanova hit the bar with her foot—9.5. Everyone decided that now, young Ira Baraksanova would surely move into the lead; her routine here is simply excellent. But she, unable to control her nerves, also fell—only 9.3…

It seemed that Mostepanova had a direct path to the coveted title—surely on beam, where she is the world champion on this event, she would not let herself be overtaken. Indeed, Olga executed the routine cleanly, freezing sculpturally in graceful balances, but she botched the dismount—9.4. And now Mostepanova found herself in third position, because Ilienko earned 9.8, and Baraksanova, with desperate determination and boldness, “spinning through” all her saltos—9.7.

Then I asked Yuri Tsapenko, a well-known former gymnast who has been training Natasha Ilienko alongside his wife for several years: “What was the most difficult thing for your student in the final?” “Getting through beam,” he answered, “and before floor, Natasha asked me: ‘Yuri Yakovlevich, please stand by the floor and encourage me.’ I know that shouting in the hall is not allowed, so I whispered: ‘Natasha, now the last pass!’ She heard everything, and everything worked out for her—9.85. Victory!” Second place was decided on the floor exercise, as well: Mostepanova scored 9.8, Baraksanova 9.7. Now the male and female gymnasts will compete in the apparatus finals.

Vladimir Golubev,

Donetsk

Sovetsky Sport, April 21, 1984

More on Age