In April 1981, a gymnast from Kharkov stepped onto the podium at Leningrad’s Yubileiny Sports Palace and won the USSR Cup in artistic gymnastics. Alla Misnik, training under coach Valentin Shumovsky, announced herself as one of Soviet gymnastics’ brightest new talents. Her uneven bars routine featured what Sovetsky Sport called “a magnificent cascade” of elements—a Tkachev, a Jaeger, clear-hip circles with pirouettes, a double-back dismount—forming what one judge described as “a routine of the future.”

A month later, Misnik traveled to Madrid for the 1981 European Championships. There, the Soviet Union’s leading gymnast did not win. She finished third in the all-around behind East Germany’s Maxi Gnauck and Romania’s Cristina Grigoraș, and earned silver medals on uneven bars and floor exercise. For a debut at a major international championship, the results were impressive.

Yet they were results that required explanation in the Soviet press. Why had the Soviet team failed to win a single gold medal? Internationally, the outcome ignited debates about the direction of women’s gymnastics. Was it really a women’s sport anymore?

What went largely unremarked at the time, however, was a more basic fact: Misnik was too young to be competing in Madrid at all.

A Birthday Problem

The European Championships were held on May 2-3, 1981. Under FIG regulations, gymnasts were required to turn at least fifteen years old during the calendar year in order to compete at senior international events. Misnik, born on August 27, 1967, would not reach that age until the 1982 season.

Sovetsky Sport had been explicit about her age just weeks earlier. In his April 19, 1981, coverage of the USSR Cup finals, journalist Vladimir Golubev noted that Misnik and fellow competitor Tatiana Frolova were “not yet fourteen.” But, Golubev pointed out, “that does not mean—so to speak—there’s ‘another kindergarten on the podium.'”

The math is inescapable: a gymnast who was “not yet fourteen” in April 1981 could not possibly turn fifteen during that calendar year, which meant that she could not possibly be eligible for senior competitions in 1981.

Yet there she was in Madrid, competing against gymnasts like Gnauck, performing routines that even Soviet officials acknowledged were more technically difficult than what her rivals were showing.

The Reputation Defense

The Soviet sports press responded to Misnik’s third-place finish not with celebration of a remarkable debut, but with barely concealed frustration at the judging. Olympic champion Olga Kovalenko, writing in Sovetsky Sport on May 22, laid out the case systematically: Misnik’s uneven bars routine was the most difficult in the world. Her beam composition demonstrated both risk and originality. Yet her scores, in Kovalenko’s opinion, were lower than they should have been, especially in relation to Gnauck’s.

“Unfortunately, once again we must speak of subjective judging and the unwritten ‘law’ by which unknown gymnasts without reputation remain in the shadows,” Kovalenko wrote. “Sadly, this happened at this tournament as well.”

The narrative was clear: Soviet gymnastics had sent its most innovative young talents to Madrid—athletes performing “models of the future”—only to see them marked down because judges didn’t recognize their names. Senior coach Aman Shaniyazov had deliberately fielded an entirely renewed lineup, testing the next generation with an eye toward the 1984 Olympics. This was framed as a strategic experiment, not a failure.

In her article, Kovalenko pressed Shaniyazov, saying, “Aman Muradovich, look what the GDR gymnast Birgit Senff has invented: a back handspring on beam followed immediately by a straddle jump. Not very technically difficult, but it looks good.”

To which, he replied, “So what? Tomorrow, everyone will be doing that. But what Alla Misnik shows—gymnasts will have to master for years.”

Polish coach Jerzy Jokiel, a 1952 silver medalist who coached his daughter in Madrid, made a similar remark. “Great things are seen at a distance—that is, in perspective.”

In other words: don’t judge these young gymnasts by today’s medals alone. Time would reveal their true impact. The innovations they were performing would eventually become the standard, and they themselves would mature into champions. It was a consoling framework—one that allowed Soviet officials to recast a disappointing result as a strategic investment in the future.

But the international press saw something very different.

“The Destruction of a Sport for Women”

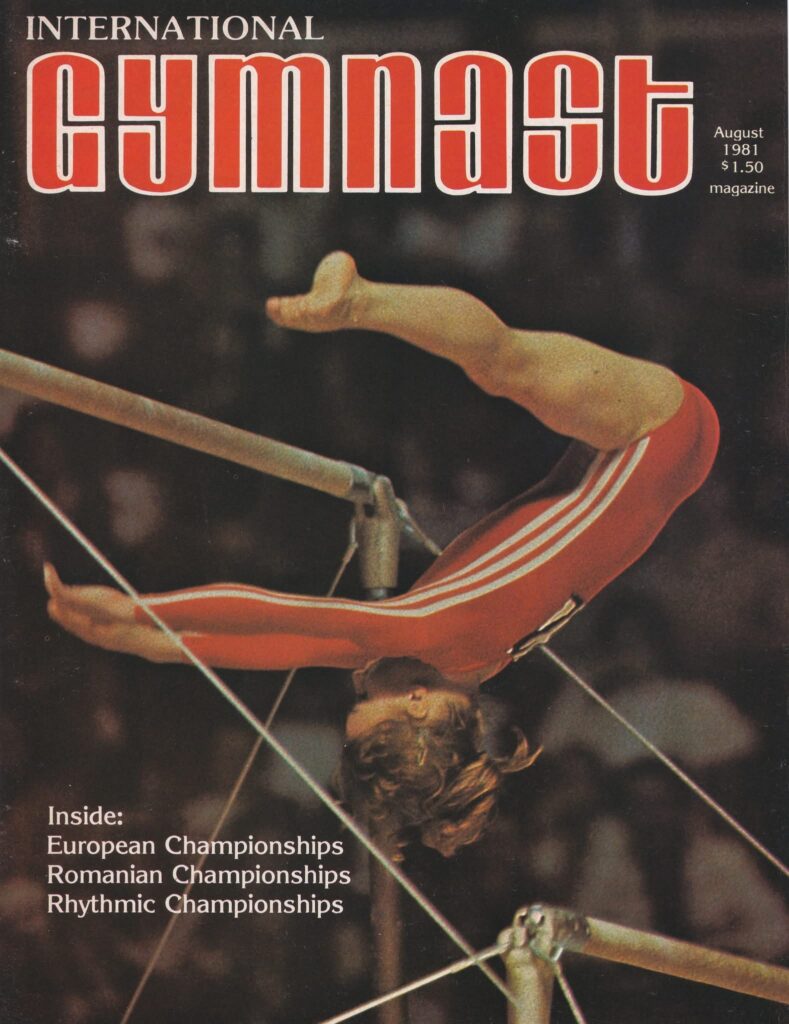

The August 1981 issue of International Gymnast magazine included a remarkable summary of German press coverage, attributed to a writer named Enrique Gonzales. The language was severe:

“The 13th edition of the title contest produced the final triumph of the gymnastics dwarves and motion robots, the destruction of a sport for women. Kids with programmed top difficulties dominated the scene, girls for whom the words of passion and enthusiasm are just terms in the dictionary.”

Gonzales reserved particular criticism for Gnauck, describing her as “a computer who does gymnastics” who showed “not even a trace of joy” at her victory. But he also catalogued the physical reality of the championship: Gnauck stood 150 centimeters tall—”almost a giant among her competitors.” Runner-up Grigoraș measured 146 centimeters.

And then there was Misnik: “Alla Misnik, who secured the bronze medal, is 14 only and can be discovered with her 137 cm only when you look more closely.”

The criticism cut to the sport’s deepest anxiety. Had women’s gymnastics become something only small children could do? Had it crossed a line from athletic expression into something inhuman? Were these competitors athletes at all or “programmed” bodies executing prewritten sequences?

What the German press couldn’t see—or chose not to say—was that behind every “motion robot” stood a system that treated young gymnasts as renewable resources in the pursuit of medals.

Eleven Tournaments

Back in the Soviet Union, Alla Misnik was in demand. She competed everywhere. “Eleven tournaments in a single season—that is simply too much!” wrote V. Golubev in Sovetsky Sport‘s coverage of the 1982 USSR Cup. “The strain took its toll: injury, illness, surgery. And now Misnik is no longer in first place, but in tenth.”

Golubev’s concern was prescient: “Are we not rushing things by admitting such extremely young girls… to the grueling adult marathon? Care, and care again, is what our talents need. Haste will lead to nothing good and will only cause harm.”

This warning was translated into English. The Northern Echo (England) wrote this about Misnik: “The Daily Sovietski Sport said over-ambitious training programmes and packed tour schedules had already ruined some of the brightest Soviet talents before they had fully developed. It named promising young gymnast Alla Misnik as a typical case. She was entered for 11 competitions in one season before she was even in her teens. The strain led to illness and eventually Alla went into hospital for an operation.”

By 1982, the gymnast who had blazed so brightly just a year earlier had been worn down by the very system that had created her.

“She Can Burn Holes in the Wall”

The press framed Misnik’s decline as a cautionary tale about excess. But behind the abstractions—“eleven tournaments,” “over-ambitious schedules,” “strain”—stood a child whose character was still forming.

Perhaps the most revealing portrait of Alla Misnik came from her coach, Valentin Shumovsky, speaking to journalists after the 1981 USSR Cup. His description mixed affection with a telling awareness of his young student’s determination:

“Well, what can I say? She’s a gymnast with experience—she started tumbling a little even back in kindergarten. Then she trained with my wife, and then I took her on. Obedient, friendly, accommodating—you pat her on the head, and she’s ready to do anything, give her soul; but if something isn’t to her liking, she keeps quiet—yet she can burn holes in the wall with her eyes.”

He continued: “She isn’t afraid of difficult elements, though sometimes she’ll stand on the upper bar with her feet and say: ‘Oh, oh, it’s so high here—and so scary…’”

Journalist Golubev added, “But Alla Mysnik’s bars are simply exemplary: the Tkachev release, giant swings, three saltos. It’s all put together firmly and logically, and the routine looks as if the performer hardly touches the bars—she freely soars through the air.”

It’s a portrait of a child—frightened by heights, capable of quiet rebellion—who had nevertheless been trained to “freely soar” through combinations that even international judges acknowledged as unprecedented in their difficulty.

The German press saw a robot. The Soviet press saw an underappreciated innovator. Shumovsky saw both a talented student and a strong-willed girl who would “burn holes in the wall with her eyes” when displeased.

What no one seemed to see clearly was simply a 13-year-old child being asked to compete at a level that would eventually break her.

The cautionary tale isn’t about Alla Misnik specifically—it’s about what happens when any gymnastics program, whether Soviet or otherwise, mismanages the talent of its athletes and pushes them to their breaking point.

Tournament debutant Alla Misnik, a seventh-grade schoolgirl from Kharkov, placed third in the all-around and went on to win two silver medals in the event finals.

Note: Seventh graders in the Soviet school system were typically 13, turning 14. (First graders entered school at seven.)

Sovetsky Sport, May 5, 1981

Note: When the Soviet gymnasts traveled to the United States in April 1982, Misnik was described as 16. With a 1967 birth year, she would have been 14, turning 15, in 1982.

Note #2: Alla Misnik died in the United States in July 2006, at age 38.

References

Primary Sources – Soviet Press

Sovetsky Sport (Советский Спорт)

“Hello, Gymnastics Spring!” Sovetsky Sport, 27 March 1981, No. 73.

“Spring Voices.” Sovetsky Sport, 31 March 1981, No. 75.

“Virtuosity Is Required.” V. Golubev. Sovetsky Sport, 15 April 1981, No. 88.

“Contours of Innovation.” V. Golubev (special correspondent). Sovetsky Sport, 17 April 1981, No. 90.

“The Charm of Novelty.” V. Golubev (special correspondent). Sovetsky Sport, 18 April 1981, No. 91.

“Their First Steps Come Easily.” V. Golubev. Sovetsky Sport, 19 April 1981, No. 91.

“Great Things Are Seen at a Distance.” Sovetsky Sport, 5 May 1981, No. 104.

“Signs of the Times: The Paths of Progress in European Women’s Gymnastics.” Olga Kovalenko. Sovetsky Sport, 22 May 1981, No. 118.

“Protect Talent.” V. Golubev (special correspondent). Sovetsky Sport, 28 May 1982, No. 122.

Gudok (Гудок)

“What Will You Say, Debutants?” I. Vanyat. Gudok, 28 March 1981, No. 73.

“‘The Main Thing Is the Search.'” I. Banyat. Gudok, 31 March 1981, No. 75.

Krasnaya Zvezda (Красная звезда)

“Prizes for Soviet Gymnasts.” M. Shlaen. Krasnaya Zvezda, 29 March 1981, No. 74.

Leningradskaya Pravda (Ленинградская Правда)

“Making Up for Lost Ground.” S. Nenmasov (Master of Sport) and S. Chesnokov. Leningradskaya Pravda, 16 April 1981, No. 90.

International Press

Göhler, Josef. “Women’s European Championships in Madrid, Spain.” International Gymnast, August 1981.

“Gym Coaches Are Warned.” Northern Echo, May 29, 1982.

Reference Works

“Misnyk Alla Vasylivna” [Мисник Алла Василівна]. Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine [Енциклопедія Сучасної України]. Institute of Encyclopedic Research, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. https://esu.com.ua/article-64657

More on Age