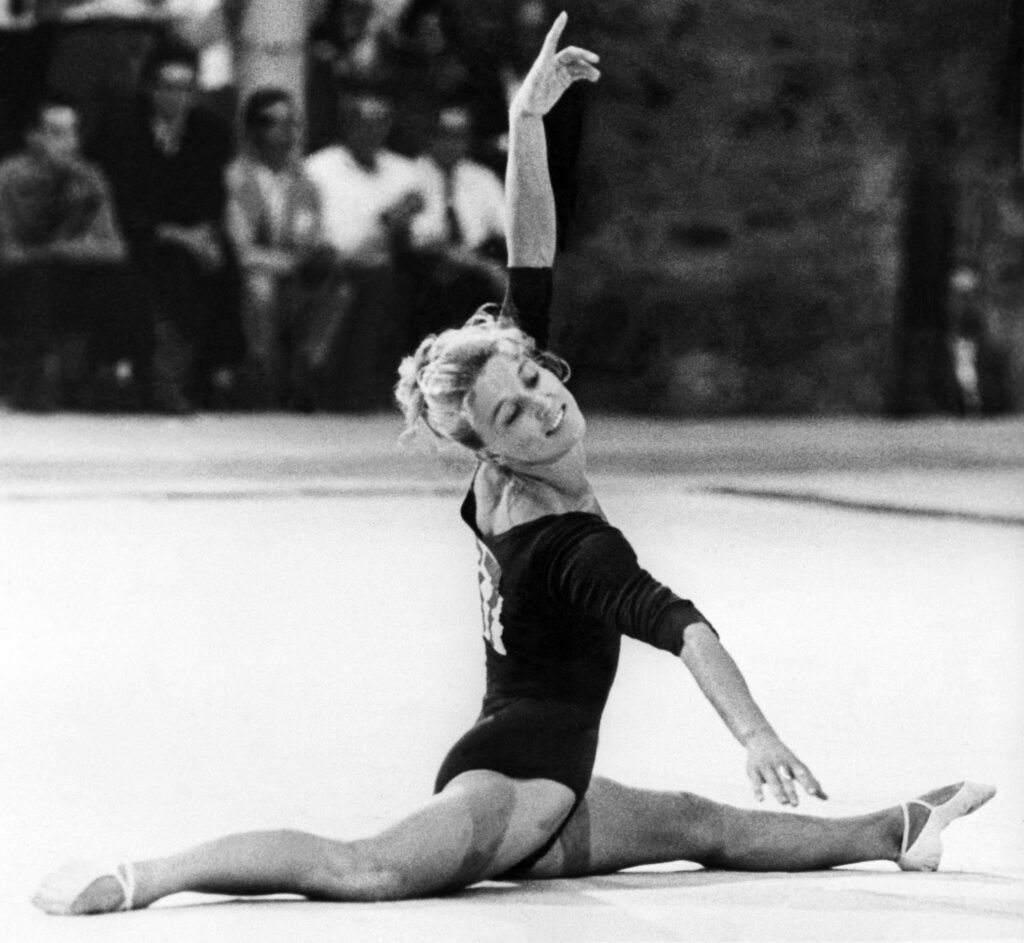

She was once called the “Russian birch”—slender, graceful, resilient. With five Olympic gold medals to her name, Polina Astakhova never flaunted her triumphs. Former teammate Natalia Kuchinskaya remembered her most vividly for a quiet act of kindness on the balance beam. Yet in competition, Astakhova was unshakable: the leader who returned to the floor only twenty minutes after tears in Rome, composed and determined.

By 1988, she was no longer the star of Rome or Tokyo but the head coach of Ukraine’s national team. At the training base in Koncha Zaspa, she spoke less about medals than about children—about the blank slates entrusted to her care, about the culture and artistry of sport, about shaping gymnasts not only as athletes but as people. Looking back, it is clear that behind the legend of the “Russian birch” was something deeper: a coach and champion who believed that strength and humanity must always go hand in hand.

FAMOUS FACES IN CLOSE-UP

THE BLUE WIND WHISPERS TO ME

Polina Astakhova

…I walk through the forest to the Olympic training base “Koncha Zaspa,” near Kyiv. The wind gently sways the fir branches. I am about to see her, the gymnast once called the “Russian birch.” Unforgettable. I am about to see five-time Olympic champion Polina Astakhova. I try to focus on business—it feels wrong to pull her away from her duties as head coach of the Ukrainian national team—but in my head, against my will, keep turning over Sergei Yesenin’s lines: “Let the blue wind whisper to me at times, that you were both song and dream…”

From a conversation with Natalia Kuchinskaya:

— Tell me about Astakhova. What is she like?

— Amazing! We were always in a rush, always demanding something. Polina Grigoryevna never demanded anything. I remember meeting her once in training. We were both working on the balance beam—she on one side, I on the other. We met in the middle. By unwritten rules in gymnastics, the younger one must yield. I was about to jump down to make way for Astakhova, but she jumped off herself, and I continued my routine. It was awkward. She came up to me and said, “Why are you embarrassed? It was easier for me to get down.” She was always like that—amazingly gentle, sensitive.

— But couldn’t that softness show even in competition, yielding out of compassion for a rival?

— You don’t understand! Competition is different, and in that arena, Astakhova was a leader. Do you think all leaders are angels, just without wings? Many are programmed-for-victory “robots,” ready to crush everything in their path. But with Astakhova, we—still such young girls—felt “warmed.”

By the way, don’t expect her to “open up” to you out of pity for your journalistic profession. Astakhova’s refinement implies restraint. She considers it improper to burden others with her memories, though with us she did like to speak about the “Russian birch.” But that’s only with us…

At our meeting, Astakhova said right away:

— Forgive me. In my work today, there are questions that trouble me deeply. That’s what I would like to talk about. For example, how to raise young gymnasts. We can teach them the most complex elements, but with upbringing, there are problems.

…Olympic Games, Rome, 1960. Astakhova was confidently leading in the all-around. She was about to perform a beam routine, one of her favorite events. She began brilliantly—and fell.

Do you remember Polina Astakhova’s tears in Rome? Doubtful. Only a few teammates saw them.

Twenty minutes later, she was back on the floor. No trace of tears. She was radiant, graceful, tender—and at the same time fully committed to the fierce struggle of sport. She could not let the team down, and she fought to the end.

— You see, for us it was easier. Grown girls, we fully understood ourselves in gymnastics; we knew what was required of us. Today it is much harder. These are just children! Before every training camp, I find myself in an absurd situation: I receive a plan for work with Komsomol members. I keep saying, “There’s only one Komsomol girl in the gym—Oksana Omelianchik. All the others are still Pioneers.” But no one listens! Yet those are the ones who need upbringing. The girls are reckless; their instinct for self-preservation is blunted, and they’ll “twist” any element before you can blink. But as people, they are still blank slates. Whatever we, the coaches, write on those pages, that is what they will become. It is very difficult to work without educators, without the old “governess” type. These girls must have everything explained, everything told.

And what were they like, back then? Larisa Latynina recalls in her book Balance:

“And again we talk unhurriedly with Lina. About what?

— About how young we once were…

— How we loved to laugh…

— How we blushed with our rosy cheeks…

— How we wore long dresses…

— How we curled our hair!..”

Astakhova laughs:

— Yes, that’s true. And how we preened before competitions! We adjusted our leotards, did our hair. So what? Everyone had to see: here comes the Soviet team—the strongest and most beautiful in the world! That, too, is a culture of communication with people, with the spectators. The very culture without which gymnastics cannot exist.

To break my pupils of sloppiness, I filmed them on camera. “Look, learn what is bad.” And then I showed them how the best athletes of the past looked. It works!

And indeed, they really were the strongest and most beautiful in the world—until the hard times of generational change came to the team. Astakhova and Latynina still competed, but it was already difficult for them to keep pace with the younger gymnasts.

…Dortmund, 1966. World Championships. For the first time in many years, the Soviet gymnasts lost the team title. The squad then was mostly young athletes—Larisa Petrik, Natalia Kuchinskaya, Zinaida Druzhinina, Olga Kharlova. And only two could answer for all and for everything—Polina Astakhova and Larisa Latynina. Latynina said:

“Tears? No, that could not be allowed. And we smiled. Sport teaches not only how to win… it teaches how to lose. We smiled, we were calm and focused.

— ‘I am counting only on you in this moment,’ our delegation leader told us. Lina and I nodded solemnly…”

Astakhova agrees:

— Losing is perhaps even harder than winning. It is harder to keep your composure, not to show how much it hurts. People must never see that. A woman, a girl, especially if all eyes are on her, must always remain beautiful.

In 1968, Astakhova parted with elite sports. She said, “I will be a coach.”

Natalia Kuchinskaya recalls:

— Polina Grigoryevna was our lead coach for a long time. What a lead she was! Always calm, kind. If you started to get nervous, she would come over, touch your shoulder, look you in the eye, say something gentle—and the nerves vanished. And I’m not even talking about how deeply she cared for the team. She remembered everything, down to the smallest detail. With her, it was always good and easy.

Good and easy… I wondered if such moments are really common in Polina Grigoryevna’s coaching life. It turned out, no:

— Strange as it may seem, a coach needs support no less than an athlete. Take just one example. Why must a Merited Coach of the USSR pass re-certification every time? Having raised a world or Olympic champion, has he not already proved his professional worth? Why should a Merited Coach, when his pupil leaves elite sports, have to start all over again, gathering a group of fifteen beginners? Of course, one way or another, you have to start again, but perhaps it would be better to allow him to take five new pupils, not fifteen? Then his expertise would yield more.

— Polina Grigoryevna, how do you feel about modern gymnastics?

— Gymnastics cannot be divided into past and present. It is one.

It pains me to see empty stands at the biggest competitions. Perhaps not everyone enjoys watching the most complex tricks. Some want to see beauty in sport. That’s why I think it makes sense to introduce different age groups for gymnasts. Let the older ones not leave the podium too early. They can take part in exhibition performances. The idols of the spectators must remain in the sport longer. People need them.

[Note: Olga Korbut had expressed a similar sentiment in her 1987 interview.]

Saying goodbye to Astakhova, I return to the city. My heart feels light—my unease has gone, dispelled by Polina Grigoryevna. And in my mind echo Yesenin’s lines:

You are as simple as everyone else,

Like a hundred thousand others

In Russia.

N. Kalugina

Sovetsky Sport, April 10, 1988

Note: Yesenin’s lines come from two different poems. The first poem is about parting and memory, and the blue evening wind is the medium through which the past speaks, gently and melancholically. The second poem is about yearning for purity and simplicity. On the surface, the lines cited sound dismissive and cruel. “You’re just like everyone else.” But those lines express a love stripped of illusion. In the lyrical subject’s view, ordinariness is a higher form of beauty. It’s the beauty of authenticity.

ИЗВЕСТНЫЕ ЛИЦА КРУПНЫМ ПЛАНОМ

МНЕ ШЕПЧЕТ СИНИЙ ВЕТЕР

Полина Астахова

…Я иду лесом на олимпийскую базу «Конча Заспа», что под Киевом. Ветер тихонько покачивает лапы елей. Мне предстоит увидеть ее, ту гимнастку, которую называли «русской березкой». Незабываемую. Мне предстоит увидеть пятикратную олимпийскую чемпионку Полину Астахову. Пытаюсь настроиться на деловой лад — все-таки отрываю от работы старшего тренера сборной Украины, а в голове против воли крутятся строки Есенина: «Пусть порой мне шепчет синий ветер, что была ты песня и мечта…».

Из разговора с Натальей Кучинской:

— Расскажи мне про Астахову. Какая она?

— Удивительная! Мы все какие-то не такие, куда-то спешим, чего-то требуем. Полина Григорьевна никогда ничего не требовала. Помню, когда-то столкнулась я с ней на тренировке. Обе работали на бревне, я — с одной стороны, она — с другой. На середине бревна сходимся. По неписаным законам в гимнастике уступить должен младший. Только я хотела соскочить со снаряда, чтобы обожать Астахову, а она спрыгнула сама, и я продолжила комбинацию. Неловко было. Астахова подошла ко мне: «Что ты смущаешься? Мне же сподручнее было соскочить». И во всем она такая — удивительно мягкая, чуткая.

— Но так можно было и на соревнованиях уступить, из сострадания к сопернице.

— Ничего ты не понял! Соревнования — дело другое, и на них Астахова была лидером. Ты думаешь, все лидеры ангелы, только что без крылышек? Среди них очень много запрограммированных на победу «роботов», которые во имя этой самой победы готовы все снести на своем пути. А около Астаховой мы, совсем молоденькие тогда девчонки, «отогревались».

Кстати, вряд ли из сострадания к журналистской профессии она перед тобой «раскроется». Астаховская интеллигентность как бы подразумевает астаховскую сдержанность. Она считает неприличным обременять людей своими воспоминаниями, хотя с нами она и любит поговорить про «русскую берёзку». Но это только с нами…

Мне Астахова при встрече сразу сказала:

— Извините. В моей сегодняшней работе есть вопросы, которые очень волнуют меня. О них и хотелось бы поговорить. Например, о том, как нам воспитывать юных гимнасток. Обучать сложнейшим элементам мы умеем, а вот с воспитанием — проблемы.

…Олимпийские игры-60. Рим. В многоборье уверенно лидировала Астахова. Ей предстояло выступать с комбинацией на бревне, одном из её любимых снарядов. Она блестяще начала упражнение и… сорвалась.

Помните ли вы слёзы Полины Астаховой в Риме? Сомнительно. Их видели только подруги по команде, да и то не все.

Через двадцать минут она снова была на помосте. Вольные. Слез как не бывало. Она очаровательна, нежна, но в то же время отдана жестокой спортивной борьбе. Она не могла подвести команду и боролась до конца.

— Понимаете, нам было легче. Взрослые девушки, мы полностью осознавали себя в гимнастике, понимали, что от нас требовалось. Нынешним гораздо труднее. Это же совсем дети! У меня перед каждым сбором возникает анекдотическая ситуация, когда получаю план работы с комсомольцами. Сколько я ни говорю, что в зале только одна комсомолка — Оксана Омельянчик, а все остальные — пионерки, меня не слушают! А ведь именно их и надо воспитывать. Девчонки отчайные, инстинкт самосохранения притуплён, любой элемент «скрутят», не успеешь оглянуться. А вот по-человечески они пока — «белые листы». Что мы, тренеры, напишем на этих листах, такими они и станут. Очень трудно работать без воспитателей, по-старому, губернаторов. Девочкам надо столько объяснять, столько рассказать.

А какие были они сами? Об этом вспоминает Лариса Латынина в своей книге «Равновесие»:

«И мы снова неспешно говорим с Линой. О чём?

— Какими мы были молодыми…

— И любили посмеяться…

— И стеснялись своих розовых щек…

— Носили длинные платья…

— Завивали волосы!..»

Астахова смеётся:

— Да, действительно, мы были такими. А как перед соревнованиями прихорашивались! «Подгоняли» купальники, делали прически. А что?! Все должны были видеть — идёт советская команда, самая сильная и красивая в мире! Это тоже культура общения с людьми, со зрителями. Та самая культура, без которой нет гимнастики.

Вот чтобы отучить своих учениц от нерашливости, я их снимала на киноплёнку. Смотри, учись, что такое плохо. А потом показываю, как выгля дели лучшие спортсменки прошлых лет. Действует!

Они и на самом деле были самыми сильными и самыми красивыми в мире, пока не настали трудные времена смены поколений в команде. Ещё выступали и Астахова, и Латынина, но им уже было трудно конкурировать с более молодыми.

…Дортмунд, 1966 год. Чемпионат мира. Первый за долгие годы, когда советские гимнастки уступили командное первенство. В сборную тогда входили в основном молодые спортсменки — Лариса Петрик, Наталья Кучинская, Зинаида Дружинина, Ольга Харлова. И только двое могли ответить за все и за всех — Полина Астахова и Лариса Латынина. Слово — Латыниной:

«Слёзы?! Нет, нельзя этого допустить. И мы улыбаемся. Спорт учит не только выигрывать… он учит и проигрывать. Мы улыбаемся, мы спокойны и сосредоточенны.

— Я только на вас и надеялся в эти минуты, — говорит нам руководитель делегации. Лина и я степенно киваем ему…».

Астахова согласна:

— Проигрывать, вероятно, даже труднее, чем выигрывать. Труднее сохранить своё лицо, не показать, как тебе больно. Люди не должны этого видеть. Женщина, девушка, особенно если на неё смотрят, должна всегда быть красива.

В 1968 году Астахова рассталась с большим спортом. Сказала: «Буду тренером».

Вспоминает Наталья Кучинская:

— Полина Григорьевна долго была у нас выводящим тренером. Какой это был выводящий! Всегда спокойна, доброжелательна. Только почувствуешь что начинаешь нервничать, подойдет, тронет за плечо, в глаза посмотрит, скажет что-нибудь ласковое, и волнения как не бывало. Я уж не говорю о том, как она интересами команды жила. Все до мелочей помнила. Нам с ней было хорошо и легко.

Хорошо и легко… Интересно было узнать, а так ли уж часто случаются в тренерской жизни Полины Григорьевны моменты, когда все «хорошо и легко». Оказалось, нет:

— Как ни странно, тренеру нужна поддержка не меньше, чем спортсмену. Вот хотя бы один такой момент. Нельзя бесконечно трепать тренерам нервы. Ну, скажите мне, зачем заслуженному тренеру СССР каждый раз проходить перетаттестацию? Разве, воспитав чемпиона мира или Олимпийских игр, он не доказал свою профессиональную состоятельность? Почему опять-таки заслуженный тренер страны после того, как разрешенный им ученик уйдет из большого спорта, должен, как новичок, набирать группу в пятнадцать человек и начинать все сначала? Конечно, начать сначала так или иначе придется, но, может быть, можно разрешить ему набирать не пятнадцать новичков, а пять? Тогда и отдача от специалиста будет больше.

— Полина Григорьевна, как вы относитесь к современной гимнастике?

— Гимнастику нельзя делить на прошлую и современную, она едина.

Мне становится больно, когда я вижу пустые трибуны на крупнейших турнирах. Может быть, не всем нравится смотреть сложнейшие трюки, комуто хочется увидеть красоту спорта? Поэтому, думаю, имеет смысл подумать и о том, чтобы ввести разные возрастные группы для гимнасток. Пусть старшие не уходят слишком рано с помоста. Они могут участвовать в показательных выступлениях. Кумиры зрителей должны жить в спорте долго. Они нужны людям.

Простившись с Астаховой, возвращаюсь в город. На сердце легко — растерянность ушла, ее развеяла Полина Григорьевна. И в голове «прокучиваются» есенинские строки:

Ты такая ж простая, как все,

Как сто тысяч других

в России.

Н. КАЛУГИНА.

More Interviews and Profiles