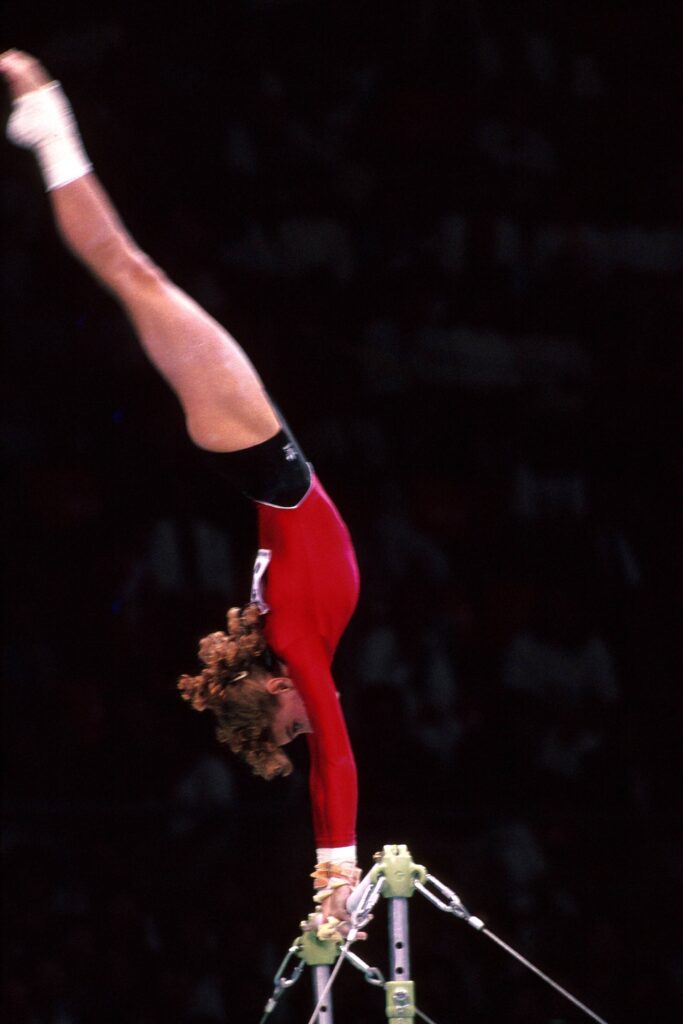

The roar in Seoul’s Olympic Gymnastics Hall is deafening as Dagmar Kersten dismounts from the uneven bars. It’s September 1988, and the seventeen-year-old has just executed an exquisite routine. Despite a small hop on the landing, a 10.0 flashes on the scoreboard. But perfection isn’t enough. Romanian Daniela Silivaș, who built an insurmountable lead after compulsories and optionals, takes gold with a perfect total of 20 points. Kersten’s silver is still East Germany’s highest finish in women’s gymnastics at these Games, confirming that the legacy of Karin Janz and Maxi Gnauck is still alive and well.

What Kersten doesn’t know—what she won’t discover until years later, after the Wall falls and the archives open—is that she’s been part of an experiment. The pills her coaches gave her weren’t just vitamins. She was a test subject in one of the most sophisticated pharmaceutical programs ever applied to athletes, a system that treated her body as a laboratory and her performance as scientific data.

“I would never have thought that something like that existed among us—it was outrageous,” Kersten would later say. “That’s why the whole process of confronting it was so shocking, as well. That’s when you realized that you had been used for such things. I had always seen the people we trusted as people who saw us as human beings. You don’t treat children like that; it’s the very last thing anyone in a position of trust should exploit. It’s also outrageous that some of this is still being covered up today. It’s a slap in the face to those who are now reading their files from back then. To deny that such things were possible at the time is an insult. There’s more than enough evidence. People always say, ‘We’d rather not talk about that.’ It’s such a shame that this topic can’t simply be discussed openly. No one wants to face it. No one wants to engage with the gymnasts of that time. We were given psychotropic drugs and OT [Oral-Turinabol]. Some of these substances were even tested by the NVA [National People’s Army]. They were supposed to help gymnasts who fell react more quickly. Anabolic steroids weren’t the only things they could give.”[1]

For decades, the gymnastics world believed its sport stood apart from the chemical manipulations reshaping track and field, swimming, and weightlifting. Doping, the conventional wisdom went, was incompatible with a discipline requiring grace, balance, and split-second coordination. Steroids built bulk; gymnastics required mobility. The logic seemed airtight.

But the archives of the Ministry for State Security tell a different story.

Note: This article is not intended as medical advice, nor does it endorse the use of steroids. It is a historical account based on a collection of Stasi files.

How Doping Worked in East Germany

What emerged in East German sport was not a collection of isolated abuses but a planned system—centrally financed, medically engineered, and designed to function out of sight. From the mid-1970s onward, roughly 10,000 athletes were enrolled in a program that treated pharmacology as part of training itself. Most were teenagers; some were children. Pills and injections arrived without explanation. Consent was never sought. Only a small inner circle of officials and scientists understood that the “supporting substances” (Unterstützende Mittel, UM) were anabolic steroids and experimental compounds. The language was deliberate: a bureaucratic vocabulary built to erase what the substances actually were.

This framework was laid out in Staatsplanthema 14.25, an internal research directive drafted in 1974 and approved at the highest levels of the sport apparatus. At its center were Manfred Höppner of the Sports Medical Service and DTSB president Manfred Ewald, supported by researchers at the FKS. Their goal was to make biochemical “support” routine: standardized, monitored, scientifically optimized, and insulated from discovery. In 1975, the Working Group on Supporting Measures (AG UM) was formed to coordinate the program across all sports. Every four years brought new secret guidelines; every season brought detailed dosing schedules, revised and circulated to federation doctors.

Behind the scenes, logistics made the system run smoothly. The State Secretary’s office and the Sports Medical Service procured the substances; the Army and Security Services supplemented supplies through their own pharmacies. Höppner’s office compiled athlete lists and dosage plans, dispatched couriers, and ensured that pills and vials reached coaches and team physicians. Trainers oversaw consumption of pills. Injections were handled by medical staff. And before any athlete left the country for competition, samples were tested at the Kreischa doping laboratory—an internal screen designed not to catch violations, but to prevent them from appearing abroad. The Stasi added another layer of protection, embedding thousands of informants throughout the sport system to watch for dissent, disclosure, or even hesitation.

Health was never the priority. In some sports—gymnastics among them—administration began astonishingly early, sometimes around age ten. Many of the compounds were experimental, their long-term consequences poorly understood. Medical records were altered, and side effects were concealed; injuries and complications could disappear into sanitized charts. Even after retirement, athletes were kept from learning what they had received. Football was the sole exception on paper—officially kept “clean” domestically to preserve equal chances—yet national team players were doped for international events, and club-level use emerged independently.

Across this landscape, the pattern remained the same: young athletes carrying the burden of decisions made far above them, unaware of the substances entering their bodies or the risks the state had quietly calculated on their behalf.

The Files

The Stasi Records Act of 1992 shed light on a world that had operated in secrecy. Among the files: State Research Plan 14.25, the centralized doping program. Research protocols from the Forschungsinstitut für Körperkultur und Sport (FSK). Experimental data from state pharmaceutical companies. And, buried within all of it, page after page documenting systematic doping in gymnastics.

The files span two decades, from the late 1960s through the collapse of East Germany in 1989. They record dosages, blood tests, psychological evaluations, EEG readings measuring brain activity, and careful notes on side effects. They describe test groups and control groups, double-blind protocols, and “follow-up investigations” tracking individual athletes over years. They document a machine designed to optimize human performance through chemistry, with young gymnasts—some as young as ten—serving as its test subjects.

And for a while, by the only metric that mattered to the state, the state-sponsored doping apparatus produced results. East Germany was a consistent contender in international gymnastics through the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, punching well above its weight for a nation of seventeen million. At the 1988 Seoul Olympics—the GDR’s final Games before reunification—Dagmar Kersten’s silver on uneven bars marked East Germany’s highest finish in women’s gymnastics. The system worked, at least on the scoreboard.

The cost would only become clear later.

The Logic of Incompatibility

The resistance to the idea of doping in gymnastics wasn’t just public relations. Many athletes genuinely believed it was impossible.

Bernd Jäger, inventor of the Jäger salto on high bar, recalled that East German scientists briefly tested anabolic steroids on gymnasts in the early 1970s but quickly abandoned the effort. “The side effects had an impact on the coordination system,” he explained years later. “There were coordination disturbances. That’s why gymnastics was more or less ruled out—because there was a danger that, say, during a triple somersault, you might no longer know which way was up or down, and could easily get injured. The coaches recognized that very quickly. So the idea was soon shelved. It was still in the experimental stage, and it simply didn’t prove effective in our sport.”[2]

Across the Iron Curtain, West German Olympian Andreas Aguilar echoed the same logic: “Gymnastics, like springboard or platform diving, is one of those sports where it has been proven that doping does little or nothing to help. Anabolic steroids that promote muscle growth are absolutely counterproductive. Muscles are extremely heavy and tend to make the body stiff. Gymnasts, however, must be flexible. Moreover, gymnasts work entirely with their own body weight, so having too much muscle would actually be a hindrance.”[3]

This “logic of incompatibility” makes intuitive sense. Few gymnasts have ever tested positive for banned substances. What’s more, steroids build mass; gymnastics requires mobility. Power comes at the expense of precision. Chemistry and artistry seem fundamentally opposed.

But the logic has a blind spot. It assumes that steroids are only about building muscle. What it misses is that anabolic agents also accelerate recovery, blunt fatigue, and modulate stress hormones—effects that could serve elite gymnasts quite well.

The Early Years: Steroids in the Shadows

One of the first mentions of doping in gymnastics appears in a 1968 Stasi memorandum. Dr. Welsch, chief physician of the Sports Medical Service, suggested that Oral-Turinabol—a synthetic steroid developed by the East German pharmaceutical company VEB Jenapharm—might be administered to male gymnasts “to increase strength.”[4]

The timing was significant. In 1968, the concept of “doping” existed more as a moral condemnation than a scientific definition for the IOC. The statutes for that year’s Olympic Games (published in 1967) stated that “the use of drugs or any kind of artificial stimulants is prohibited,”[5] but offered no detailed list of banned substances or testing protocols. This regulatory ambiguity created vast interpretive space. East German sports scientists could rationalize their interventions as “medical support” or “scientific preparation” rather than cheating.

Anabolic steroids weren’t added to the IOC’s prohibited list until 1975, after new testing methods made detection possible. But even then, the controls were primitive. At the 1976 Montreal Olympics, the IOC’s first steroid tests could only catch drugs taken within three weeks of testing. Out of 275 tests for such substances, just eight athletes tested positive.

During this window of regulatory limbo, East Germany built an elaborate system around substances that weren’t explicitly banned. Wolfgang Thüne, a world silver medalist on high bar who defected to West Germany in 1975, recalled that “since 1971, pills had enriched athletes’ diets; their composition was secret.”[6] After his defection, Thüne spoke openly about anabolic agents and even, as historian Brigitte Berendonk notes, “warmly recommended these ‘supportive substances’ to his Western colleagues.”[7]

The Side Effects

Yet, for all the endorsements by gymnasts like Thüne, the steroids didn’t work cleanly for the male gymnasts already using them.

Training reports from the 1970s describe a distinctive and troubling pattern emerging across East German gyms. Athletes on high doses of anabolic agents began losing the ability to relax their muscles after training sessions ended. The phenomenon was consistent enough to alarm coaches and medical observers: even at rest, muscle tone remained abnormally high. What began as persistent tension sometimes progressed into painful spasms affecting entire body regions.

The subjective experience was equally disturbing. Gymnasts reported feeling perpetually tense and uneasy, unable to achieve the mental quietness that normally followed physical exertion. Sleep became difficult. Their bodies refused to release the day’s training, muscles remaining contracted and vigilant through the night. Cramping was common. Fine motor control—the foundation of everything in gymnastics—began to deteriorate.

The most alarming effects appeared during movements requiring little force or strength. In these small, delicate actions—the kind that separated elite gymnasts from merely good ones—coordination became clumsy or jerky. A hand placement that should have been automatic suddenly required conscious thought. A weight shift that should have been fluid became hesitant.

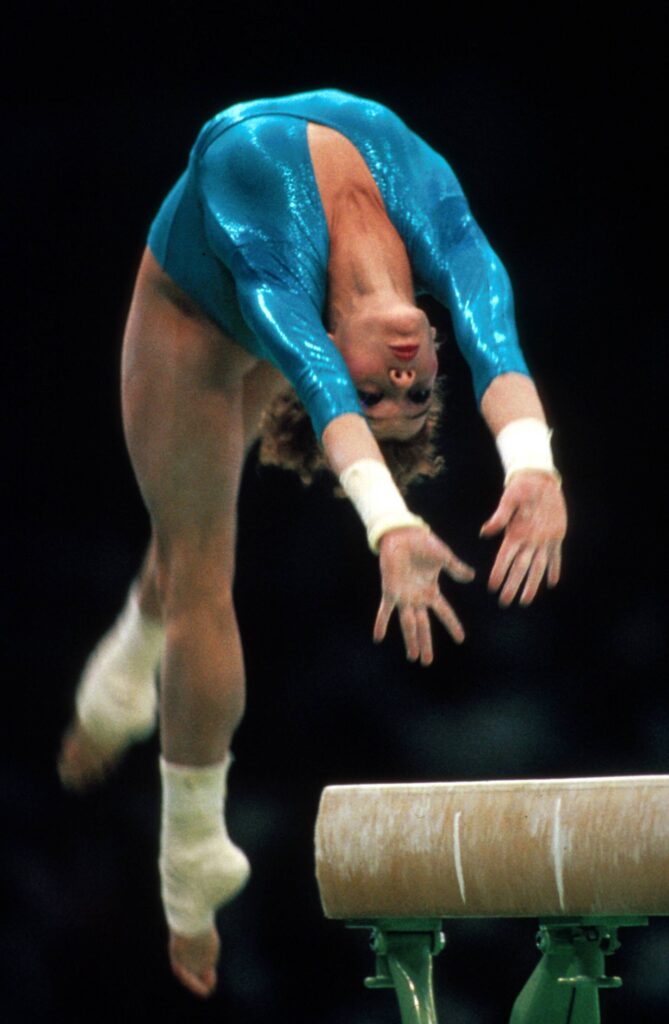

On pommel horse, the consequences were immediate and visible. Gymnasts who had trained the skill for years suddenly missed their grip on the handles. The loss of fine motor control led to falls, and falls led to injuries. The paradox was stark and troubling: athletes were growing stronger yet simultaneously less capable of using that strength with the precision their sport demanded. Power came at the expense of control.

The reports reveal something else: despite these documented effects, despite visible deterioration in coordination, the experiments not only continued but intensified. And male gymnasts were not the only ones experiencing the side effects of anabolic steroids. Adolescent girls were, too.

Frau E.: A Child Athlete in the System

The story of one gymnast, documented by the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Commissioner for Processing the SED Dictatorship (i.e., East Germany), reveals how early the doping of female gymnasts began—and how it was justified.

A former competitive gymnast, identified as “Frau E.,” started training in 1971. For six years, she trained in a sports club, her young body absorbing the relentless demands of elite gymnastics. By 1973, at age twelve, her sports medical files documented constant trouble with her knees—the kind of injuries that should have ended her training or at least required extended rest and recovery.

Instead, doctors prescribed the Kaiser-Schema, which included anabolic steroids to get her back into training as quickly as possible. Her first documented dose came when she was twelve years old.

The Kaiser-Schema, or Osteochondroseprogramm, had been developed by Professor Kaiser, a senior physician at the Charité hospital. Purportedly, it was a treatment for developmental disorders affecting bone and cartilage growth. The protocol allowed doctors to prescribe Oral-Turinabol, among other drugs, to children with skeletal problems. What may have begun as a legitimate medical therapy became a tool for keeping injured children training. Rather than rest, young athletes received steroids. Rather than recovery, they got a pharmaceutical pathway back to the gym.

The drugs had severe consequences. They led to premature closure of growth plates, permanently stunting physical development. For this reason, the Kaiser-Schema was routinely used in GDR elite sports in disciplines where small body size was advantageous—gymnastics being a prime example. More than 200 young athletes in the German Democratic Republic’s elite sports would eventually be “treated” this way. The most extreme documented case involved a ten-year-old female gymnast from SC Dynamo Berlin who received 5 mg of Oral-Turinabol daily for three months.

Frau E. described intense psychological and physical pressure, along with violations of her personal boundaries and constant, overwhelming stress from being given performance-enhancing drugs and painkillers. Today, decades later, she suffers from severe joint problems in her elbows, knees, and hips that gravely impair her quality of life. Her case became part of the legal reckoning after reunification, documented in compensation claims under the Victims of Doping Assistance Act.[8]

Her story reveals something crucial. Female gymnasts were not exceptions or late arrivals to the doping system. They were part of it from the beginning. What made their inclusion possible was the Kaiser-Schema itself, which offered a convenient medical pretext. By framing steroid use as a therapeutic intervention rather than performance enhancement, doctors could administer banned substances to children while claiming to be protecting their health. The language of medicine became the system’s shield: healing as justification for harm.

To be sure, the question of intent remains contested. Historian Giselher Spitzer, after analyzing hundreds of Stasi documents, concluded: “The Kaiser-Schema, originally designed as a medical therapy for children, was misused for the continuous administration of anabolic steroids—if it was not actually conceived for this purpose in the first place.”[9] The doctors who used the Kaiser-Schema have maintained a different position: they insist they did not “dope” the gymnasts but merely followed accepted medical protocols in the GDR, and those protocols included banned substances.

In either case, the outcomes for athletes like Frau E. were the same: permanent damage to joints that were never allowed to heal, suffering that compounds with age, and bodies that still bear the cost of decisions made for them when they were twelve.

STS 646 and the Illegal Search for Undetectability (1979-1982)

While doctors administered steroids through the Kaiser-Schema, chemists pursued a complementary goal: developing new compounds tailored to the demands of elite sports. Between 1979 and 1981, researchers at the Central Institute for Microbiology and Experimental Therapy developed Mestanolone, known internally as STS 646—a synthetic steroid not approved for human use, making it illegal under GDR law.

Male gymnasts from the Army Sports Club (ASK) and female gymnasts from the Olympic team and national team were among the test subjects. The stated purpose was “to increase training tolerance without major change in body mass; psychotropic effect.” The strategic thinking was clear: the purpose of doping in gymnastics wasn’t to build muscle but to help the body recover from competition and survive rigorous training. Scientists aimed to sustain gymnasts through training loads that would otherwise break them—harder sessions, longer hours, fewer injuries, relentless progression without pause.

But recovery alone wasn’t enough. To make the doping machine work, the drugs had to avoid detection.

The Clearance Studies

The research began with canoeists. When athletes received daily doses of 10 to 20 milligrams of STS 646, researchers tracked exactly when traces disappeared from urine. They called this the Abklingrate—the decay rate. The results were consistent: two to five days after the final dose, the compound vanished from detection.

Scientists conducted parallel testing using both radioimmunoassay (RIA) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS)—the two primary methods used by international doping laboratories—to ensure their athletes would test clean under either protocol. In one study, five canoeists were tracked daily after their final doses. The precision was remarkable: researchers documented exactly when each testing method would no longer detect the substance.

For officials responsible for doping control, these numbers were essential. They offered a predictable interval between administration and a negative test result. Performance-enhancing substances could be used during the hardest training phases, then stopped in time to pass international controls.

The Brain Experiments

In 1982, researchers expanded their inquiry. The reference to “psychotropic effect” in the earlier STS 646 trials hinted at something beyond physical recovery. Could steroids influence not just muscles but minds, sharpening motivation, dampening anxiety, and improving concentration under pressure?

Two studies—Turnen 1 and Turnen 2—tested this question. Male gymnasts aged fourteen to nineteen were divided into groups: some received Oral-Turinabol, others the illegal compound STS 646, and a control group took placebo tablets. Scientists tracked brain-wave readings through electroencephalograms (EEGs), administered psychological questionnaires, and measured blood samples for hormones including testosterone, insulin, and cortisol. Training was kept consistent: the first daily session covered floor exercise, pommel horse, and rings; the second covered vault, parallel bars, and horizontal bar.

The experiments tested what scientists called “zentralnervöse Aktivierung“—central-nervous activation—essentially the body’s ability to stay alert and coordinated under strain. Three months separated Turnen 1 from Turnen 2, allowing researchers to refine their protocols. The studies were less about proven effects than about looking for signs—tiny shifts in brain-wave patterns that could be interpreted as improved mental control. The gymnasts—some barely into adolescence—effectively served as live test models while scientists searched for the faintest indication that chemistry could optimize the physiological-psychological connection.

Staying Ahead of Detection

Taken together, the work from 1979 to 1982 represented a significant expansion of East German sports pharmacology. Alongside the continued use of high-dose steroids in sports like track and field, swimming, and weightlifting, researchers were developing new compounds, refining clearance timing, and exploring how drugs might influence not just muscles but minds.

This coordinated approach helps explain one of the great mysteries of Cold War sports: why positive tests in gymnastics were virtually nonexistent. It wasn’t the absence of doping. It was the success of chemists and sports physicians who stayed ahead of control laboratories, developing new compounds like STS 646, refining clearance protocols, timing administrations with precision, and testing athletes before they left the country for competitions.

The Neurochemical Turn

Testing clean was not East Germany’s only concern in the 1980s. The steroids that had powered Olympic success were destroying the bodies of the athletes who took them.

Archival documents from Staatsplanthema 14.25—the state’s central sports research program—make clear that Oral-Turinabol remained in active use across multiple sports throughout this period, with researchers documenting steady usage through 1984. Yet the consequences were sometimes severe. In 1987, after scientists combined two steroids (Oral-Turinabol and STS 646), a female athlete’s liver enzymes spiked to troublesome levels—more than six times normal for one enzyme, over double for another.

The solution wasn’t to stop using anabolic steroids. It was to experiment differently.

On October 23, 1984, Staatsplanthema 14.25 established a new research direction focused on “pharmacological influence of central nervous, endocrine, and neuromuscular control and regulatory processes.” The scientists were frank about their reasoning: while traditional psychopharmaceuticals offered a “high probability of acute increase in competition performance,” the “expected side effects do not justify the application.”

Rather than relying solely on traditional stimulants or sedatives, they would test a different class of psychoactive substances—neuroleptics and neuropeptides, naturally occurring molecules that could modulate brain function while, in some cases, remaining undetectable in doping controls.

For gymnasts, the implications were profound. Sports requiring split-second timing and absolute body control didn’t necessarily benefit from additional muscle mass. But a nervous system that processed information faster, maintained focus under pressure, and coordinated complex movements with minimal wasted effort offered distinct advantages.

These neurological interventions worked at a different level than steroids—not by changing what the body could do, but by optimizing how efficiently the brain could command it to perform.

The age of psychotropic doping in gymnastics was officially here.

Engineering the Mind

LVP

The shift began with Lysin-Vasopressin, a compound derived from a natural hormone involved in memory and attention. Between 1984 and 1988, researchers at the Institute for Aviation Medicine in Königsbrück tested it on eleven male gymnasts, along with fencers, shooters, and cyclists, in experimental cycles that stretched across years. The protocol was clinical: LVP versus placebo sprays, EEG electrodes measuring brain waves, and data collected during training and competition. The promise was elegant: sharpen focus, steady coordination, keep heart rate calm under pressure—all without the cardiovascular strain of stimulants.

The early tests offered tantalizing hints. Athletes ran through grueling visual concentration tasks while scientists monitored their bodies and minds. Most performed better on LVP—sharper, more precise, fewer mistakes. The strange part: their heart rates barely budged. They were doing more with less effort, as if the drug had made their brains more efficient.

But the effects weren’t universal. Gymnasts and shooters—athletes who succeed in millimeters—showed the clearest improvements. Cyclists grinding through endurance tests saw nothing. Neither did soccer players. Even among gymnasts, results swung wildly.

Psychology offered a clue. LVP worked best on confident athletes, the ones who believed they’d succeed. Athletes plagued by self-doubt? The drug flopped. Even stranger: it affected mood in unexpected ways. When scientists compared LVP to a saltwater placebo, seven out of eleven athletes felt more hopeful on the drug. Three felt less hopeful—and in those three, LVP produced no performance improvement at all.

The implication was clear: neurochemical interventions would require matching specific drugs to specific psychological profiles.

OXT

Oxytocin had been used for years in East German shooting and gymnastics, but it was inconsistent. Roughly one-third of athletes showed no response at all. The breakthrough came when scientists tested it under controlled laboratory conditions, using EEG readings and hormone profiles to track what was actually happening in athletes’ brains. They discovered something unexpected: oxytocin didn’t just activate the nervous system—it calibrated it.

The drug worked by adjusting neural activation to match the demands of the task. In some athletes, it damped down excessive central nervous system excitement. In others, it activated sluggish responses. The scientists found it could both lower sensory thresholds and raise thresholds for distracting stimuli—essentially helping the brain tune out interference while staying locked on target.

Both stress-prone athletes and undermotivated ones benefited, as if oxytocin simply dialed each brain to its optimal working state. This made it ideal for sports demanding fine motor coordination and sustained concentration, such as shooting and artistic gymnastics.

Yet troubling patterns emerged. Athletes often performed better than they’d expected under oxytocin—then reported feeling “exhausted” and “spent” afterward, as if the drug had wrung every drop of focus from their nervous systems.

SP

By 1987, researchers turned to Substance P, targeting a specific type of athlete: those who trained well but crumbled under competitive pressure. In animal experiments, Substance P worked through the dopamine system, extending waking states and raising vigilance levels. In humans tested at laboratory stations, it shortened reaction times and reduced errors on concentration tests. The Institute for Drug Research in Berlin developed nasal drops, which were later switched to a spray and tested on gymnasts, fencers, and shooters between 1987 and 1989.

At Königsbrück, two male gymnasts underwent repeated testing to rule out learning effects. Results showed genuine performance improvements. One gymnast used it successfully in both training and competition: in training, it helped with what scientists called Überwindungsfähigkeit—the ability to push through and master extremely difficult elements—and in competition, for performing routines cleanly from start to finish. A pilot study with four female gymnasts from ASK Frankfurt confirmed the pattern.

But the scientists admitted significant limitations. The high expectations for Substance P “could not be fulfilled under laboratory, training, and competition conditions.” The drug worked best on athletes who, “due to psycho-emotional problems, could not fully exploit their performance capacity.”

Still, the report concluded it should be administered for several days before competition, not just as a one-time dose. And, buried in the summary table, one crucial detail appeared: Substance P was “not yet detectable in doping control.”

Racing the IOC’s Clock

Yet. Not yet detectable.

The scientists were up against the clock as they experimented with new chemical compounds.

Between 1986 and 1988, researchers tested ACTH 4-10—a synthetic fragment of adrenocorticotropic hormone—on five male gymnasts at Königsbrück in double-blind trials. The goal was to regulate emotion itself—to chemically adjust how athletes responded to competitive pressure.

Results varied dramatically depending on personality type. Introverted gymnasts displayed what scientists called “dramatically improved operational reliability”—faster decisions, sharper accuracy, a noticeable leap in performance under pressure. Three success-oriented gymnasts, by contrast, responded better to LVP.

These experiments operated in a crucial regulatory blind spot. At the 1988 Seoul Olympics, the IOC hadn’t yet prohibited pituitary peptide hormones in a dedicated class. The Medical Commission only added that category in 1989, explicitly naming ACTH alongside human growth hormone and erythropoietin. East German researchers had conducted their entire ACTH program—from 1986 through Seoul—before the substance was formally banned.

The Assembled Arsenal

By Seoul, East German sports scientists had assembled a sophisticated pharmacological system: steroids for strength, recovery, and stunting growth, LVP for coordination and confidence, oxytocin for neural calibration, Substance P for stress resistance, and ACTH for emotional regulation. Each compound addressed a specific constraint. Each required careful matching to personality type and psychological state.

On paper, it appeared as a triumph of applied science: performance optimization through neurochemical control tailored to individual psychology. Yet even as researchers refined their protocols, warnings emerged from within the system itself.

The Breaking Point

By the late 1980s, even insiders began to see that their doping programs and training regimens were destroying the athletes it was meant to perfect.

One Stasi meeting report from 1988—summarizing a conversation with Dr. Berndt Pansold, then a sports physician at SC Dynamo Berlin, where Dagmar Kersten trained—recorded his concern that “all top-level female gymnasts have significant injuries, especially in the spinal area. A continuation in the present form would lead to permanent damage.”

The Stasi informant’s notes capture a growing unease within the medical staff. A consulting physician had refused to take responsibility unless training practices changed, while coaches accused doctors of being “unwilling to take risks.” According to the collaborator’s summary of Pansold’s remarks, the limits of what the human body could endure had already been reached:

“From a formal medical standpoint, continuing this training would actually no longer be justifiable. According to the medical knowledge available so far, under today’s extreme stress conditions (no longer comparable with the time of JANZ or GNAUCK), changes have occurred in the internal processes of connective and supporting tissue that go far beyond the previous patterns of stress damage in gymnastics. It must be assumed that the limit of stress capacity for the connective and supporting apparatus has been reached.” [10]

According to historian Giselher Spitzer, the real problem wasn’t just that gymnasts were training too hard. It was that East Germany was combining extremely intense training with steroids and other drugs, and this combination was physically changing athletes’ bones, tendons, ligaments, fascia, and cartilage in harmful ways.

The machinery had reached its limit. The bodies couldn’t take any more.

After the Fall

When the Berlin Wall came down in November 1989, the apparatus of East German sports medicine collapsed with it. The files were scattered; some were destroyed, but others survived, ending up in the Stasi archives. Slowly, painstakingly, historians began piecing together what had happened.

Not until the late 1990s, during the Berlin doping trials, did any public acknowledgment emerge. Dr. Manfred Höppner, deputy head of the Sports Medical Service, issued a formal apology: “I deeply regret that I was not able to protect all athletes from harm. I beg those athletes who suffered ill-health to accept my apologies for this.”

His admission stood largely alone. There was no collective reckoning, no truth commission, no coordinated attempt to contact every athlete who had been part of the experiments and inform them of what had been done to their bodies.

The silence extended to the upper echelons of the gymnastics administration. Klaus Heller, who served as head of the German Gymnastics Federation (DTV), later acknowledged the institutional awareness while maintaining distance from direct responsibility: “As the top official of the DTV, I had no official connection to it. Only those who couldn’t be left out were involved—you can’t leave out a doctor, you can’t leave out a coach, you can’t leave out an athlete, that’s it. So, they knew about it.” Yet he admitted receiving information from federation doctors: “Of course, we also got information from the federation doctors. So I knew that there was ‘rebuilding training.’ With the girls, for example, they were quite biologically underdeveloped — there’s something in medicine called the Kaiser-Schema, for anorexic or muscle-deficient people, a medical thing that falls under doping. That’s when they essentially initiated the Kaiser-Schema. Those girls didn’t compete for about a year; they were around 13 or 14. I felt very sorry for how the girls in gymnastics were treated by our coaches. With the men, they were buddies, so it was different. There is no elite sport without doping — that’s still how it’s done today, just without the GDR.”[11]

What Heller described in administrative terms—”rebuilding training,” the “Kaiser-Schema,” a year without competitions—had a very different meaning for the young gymnasts who lived through it. For athletes like Dagmar Kersten, the discovery of what these terms actually meant came through individual initiative—requesting their own Stasi files, reading through pages of clinical documentation, learning that the trusted adults in their lives had been deceiving them for years. After a severe back injury, she, like Frau E., was prescribed the so-called Kaiser-Schema, but the concept of informed consent was irrelevant in that world: “On the one hand, we received doping substances from the coaches, in tablet form. My coach told me at the time that these were substances also given to infants to help with bone development. On the other hand, we were, of course, also injected by doctors or given chewing gum and so on — but I can’t say exactly how the doping substances were packaged; I didn’t notice that.”[12]

Kersten’s words capture the essential betrayal: coaches framing anabolic steroids as infant vitamins, doctors administering injections without explanation, the entire apparatus of trust weaponized against the athletes it claimed to serve.

The Lesson

The story of East German gymnastics doping isn’t just about one country’s sports program. It’s about what happens when the pursuit of excellence becomes untethered from ethics, when science serves victory rather than health, when children become test subjects rather than just that—children.

The doping apparatus’s sophistication was remarkable: double-blind protocols, careful dosing schedules, psychological profiling, strategic timing to evade detection. These weren’t mad scientists conducting rogue experiments. They were researchers following the scientific method, documenting their work, filing reports, and trying to advance human potential. And that’s what makes it disturbing. The machinery worked exactly as designed. The problem was the design itself—a system that treated bodies as laboratories, performance as data, and human cost as acceptable collateral in the pursuit of medals.

The files show that, even in a sport ostensibly incompatible with doping, chemistry had entered the equation. Regulatory gaps were exploited. New compounds were developed specifically to evade detection. The line between medical support and pharmaceutical manipulation was deliberately blurred.

The athletes’ own words, spoken years later, reveal something harder to quantify: the betrayal felt by those who discovered that their achievements had been chemically assisted without their knowledge or consent, that the adults they trusted had been lying to them, and that their bodies had been altered in ways they’re still discovering.

Young athletes still chase perfection in gyms across the world. They trust their coaches, follow their doctors’ instructions, and believe the adults who promise to help them achieve their dreams. Dagmar Kersten was told the tablets would help her bones develop, like infant medicine. She believed it because why wouldn’t she? Children don’t consent to experiments. They don’t parse the difference between medical care and pharmaceutical manipulation. They trust, and they train, and years later, they discover what was done to them.

“You don’t treat children like that,” Kersten said. “It’s the very last thing anyone in a position of trust should exploit.”

The East German system fell more than three decades ago. But the questions it raises remain urgent: What are the limits of performance enhancement? Who decides where to draw the line? What responsibilities do we have to athletes whose bodies we shape, train, and push to their limits?

The files from the Stasi archives don’t answer those questions. But they make clear we can’t avoid asking them because the lesson isn’t about regulatory frameworks or detection methods. It’s about the obligation owed to young athletes who place their bodies and futures in the hands of adults. No achievement justifies betraying that trust.

Nothing does.

Original Quotes

[1] „Ich hätte nie damit gerechnet, dass es sowas bei uns gab, das war ungeheuerlich. Deswegen war auch die ganze Aufarbeitung so ungeheuerlich. Da hat man erkannt, dass man für solche Dinge missbraucht wurde. Ich hatte in unseren Bezugspersonen immer Menschen gesehen, die in uns Menschen gesehen hatten. So geht man mit Kindern nicht um, das ist das Allerletzte, was man als Vertrauensperson ausnutzen sollte. Es ist auch ungeheuerlich, dass das teilweise heute verschwiegen wird. Das ist eine Ohrfeige für die Leute, die ihre Akten von damals lesen. Wenn man den Leuten abspricht, dass es damals nicht möglich war, dann ist das eine Frechheit. Es ist genug nachgewiesen. Es wird immer gesagt: “Da reden wir lieber nicht drüber” […] Es ist so schade, warum man das Thema nicht einfach ansprechen kann. Keiner will es wahrhaben. Keiner will sich mit den Turnerinnen von damals auseinandersetzen. Wir haben Psychopharmaka und OT bekommen. Teilweise wurden diese Substanzen bei der NVA getestet. Sie sollten helfen, dass Turner, die stürzen, schneller reagieren können. Anabolika waren nicht das Einzige, was man geben konnte.” Tamara Wewerka, Wende- und Transformationsprozess im Turnen, 1989/1990 (2015)

[2] „Die Nebenwirkungen hatten auf das koordinative System einen Einfluss. Es kam zu koordinativen Störungen. Deshalb ist Turnen mehr oder weniger ausgeschlossen worden, weil die Gefahr, dass man praktisch beim Dreifachsalto nicht mehr wusste, wo oben und unten ist, dass man sich da leicht verletzen konnte. Das haben die Trainer sehr schnell erkannt. Dann hat man das sehr schnell ad acta geschoben. Es war im Versuchsstadium, es hat sich in unserer Sportart einfach nicht bewährt.“ — Tamara Wewerka, Wende- und Transformationsprozess im Turnen, 1989/1990 (2015)

[3] „Turnen zählt ja ähnlich wie Kunst- oder Turmspringen zu den Sportarten, wo es nachweislich nichts oder wenig bringt zu dopen […] Anabolika für Muskelwachstum sind absolut kontraproduktiv. Muskeln sind extrem schwer und machen eher steif. Turner müssen aber gelenkig sein. Außerdem arbeitet der Turner rein mit seinem eigenen Körpergewicht. Somit wären zu viele Muskeln auch ein Hindernis.“ — Tamara Wewerka, Wende- und Transformationsprozess im Turnen, 1989/1990 (2015).

[4] „Der IM berichtete erneut über leichtfertiges Verhalten des Dr. Welsch bezüglich der Behandlung von Sportlern mit leistungsfördernden Arzneimitteln. Dr. Welsch hat danach vor der ganzen Leitung des Sportmedizinischen Dienstes der Meinung Ausdruck verliehen, es sei richtig, der Männer-Nationalmannschaft Turnen zur Kraftanreicherung das Präparat Turinabol zu verabreichen. Bei dem Turinabol handelt es sich um ein Arzneimittel, das unter die Dopingmittel gezählt wird …“ — BStU MfS A-479/85, II, 4, Treffberichte vom 31.7.1968 und 7.7.1970.

[5] “L’usage de drogues ou de stimulants artificiels quelconques est prohibé. Toute personne qui donne ou reçoit du doping, sous une forme quelconque, ne peut participer aux Jeux Olympiques. Si un athlète est convaincu de doping, son équipe entière dans le sport en cause sera disqualifiée.”—Les Jeux Olympiques : statuts et règles, conditions d’admission, informations générales, conditions exigées des villes candidates à l’organisation des Jeux Olympiques, Comité International Olympique, 1967

[6] „Seit 1971, verriet der frühere DDR-Turner Wolfgang Thüne, hätten Pillen die Athleten-Kost angereichert: ‚Ihre Zusammensetzung war geheim.‘“ — Der Spiegel, 3 April 1977.

[7] Auch der 1975 aus der DDR geflüchtete Turner Wolfgang Thüne (Vizeweltmeister am Reck) machte öffentlich aus seine Anabolikaerfahrung im real existierenden Sozialismus keinen Hel und empfahl – wie Dr. Mader – diese “unterstützenden Mittel” wärmstens seinen westlichen Kollegen. — Brigitte Berendonk, Doping Dokumente: Von der Forschung zum Betrug (Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1991).

[8] Fallbeispiel Frau E.

Frau E. wird bereits seit vielen Jahren durch die Behörde der Landesbeauftragten beraten und begleitet. Die ehemalige Leistungssportlerin war über das Zweite Dopingopfer-Hilfegesetz entschädigt worden. Wegen der Verschlimmerung der Erkrankungen und der daraus resultierenden gesundheitlichen Einschränkungen wurde der Betroffenen in der Beratung empfohlen, einen Antrag nach dem Opferentschädigungsgesetz (OEG) zu stellen. Die Sportlerin trainierte seit 1971 sechs Jahre lang als Turnerin in einem Sportclub. Die ausfindig gemachte sportmedizinische Akte weist seit 1973 massive Kniebeschwerden bei der Betroffenen auf, die zu wiederholten Behandlungen führten. Um möglichst schnell wieder in das Training einsteigen zu können, wurde ihr nachweislich 1973 das sogenannte Kaiser-Schema verabreicht. Diese Behandlungsmethode sah u. a. die Vergabe von anabolen Steroiden vor und wurde im Sport auch zur Leistungssteigerung und damit medizinisch nicht indiziert eingesetzt. Bei Frau E. ist die Einnahme der anabolen Steroide im Alter von 12 Jahren erstmalig dokumentiert. In dieser Altersstufe führen diese Präparate zu einem vorzeitigen Epiphysfugen-Schluss und damit zu Störungen des Körperwachstums in Form eines verminderten Längenwachstums. Daher wurde das Kaiser-Schema im DDR-Leistungssport nicht selten in Sportarten angewendet, wo eine geringe Körpergröße von Vorteil war – wie im Turnen. In mehreren Beratungsgesprächen berichtete die ehemalige Leistungssportlerin von massivem psychischen und physischen Druck, einhergehend mit Grenzüberschreitungen sowie komplexer Überlastung, wodurch die Vergabe von leistungssteigernden und Schmerzmitteln befördert wurde.

Frau E. leidet heute unter massiven Beschwerden in unterschiedlichen Gelenken, wie z. B. Ellenbogen, Knie und Hüften, die sie gravierend beeinträchtigen. Mit Unterstützung der Landesbeauftragten stellte die Betroffene beim Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales einen Antrag nach dem Opferentschädigungsgesetz. Leistungen nach dem Opferentschädigungsgesetz können für in der DDR verursachte Schädigungen nur unter den engen Voraussetzungen einer Härteregelung beantragt werden, wenn Betroffene allein infolge dieser Schädigung schwerbeschädigt und bedürftig sind. Bei einer Anerkennung nach dem OEG haben Betroffene je nach Schwere der Schädigung Anspruch auf Leistungen nach dem Bundesversorgungsgesetz wie Heil- und Hilfsmittel oder regelmäßige Ausgleichszahlungen.

Ende 2019 wurde der Antrag abgelehnt mit der Begründung, es könne kein direkter Zusammenhang zwischen der Einwirkung durch die Medikamentenvergabe und den körperlichen Folgen hergestellt werden. Die Landesbeauftragte unterstützte den Widerspruch der Betroffenen und stellte dem Landesamt weitergehende Informationen und Unterlagen zur Verfügung. Gegen die Ablehnung des Widerspruchs reichte Frau E. eine Klage beim Sozialgericht ein. Auch in diesem Verfahren wird die Betroffene durch die Bürgerberatung begleitet. Für Frau E. konnte die Verabreichung von Dopingmitteln belegt werden, obwohl das DDR-Dopingsystem einer hohen Geheimhaltung unterlag. Nun muss das Gericht feststellen, ob die bei Frau E. bestehenden gravierenden physischen und psychischen Schäden durch die Verabreichung von anabolen Steroiden im Kindesalter zur Steigerung der Leistung und zur Beschleunigung der Rekonvaleszenz verursacht wurden.—Unterrichtung durch die Landesbeauftragte für Mecklenburg-Vorpommern für die Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur, Jahresbericht 2020

[9] „Das ursprünglich als eine ärztliche Therapie für Kinder angelegte Kaiser-Schema wurde zur Dauervergabe von Anabolika missbraucht, wenn es nicht sogar zu diesem Zweck erdacht wurde.“ — Giselher Spitzer, Sicherungsvorgang Sport, 2005.

For more on the Kaiser-Schema, see also André Keil, “Das systematische Doping im DDR-Leistungsport,” Trauma und Gewalt, May 2018.

[10] Ergebnisse der Menschenexperimente ohne Grundlagenforschung: Neue Schadensbilder im Turnen der achtziger Jahre.

Die Akte, in der die handschriftlichen Mitteilungen des Arztes Dr. med. Berndt PANSOLD an das Ministerium für Staatssicherheit und Treffberichte seines Führungsoffiziers aufbewahrt werden, enthält auch Angaben zu völlig neuen Schadensbildern im Turnen der achtziger Jahre. Laut MfS teilte der Mediziner 1988 während der Vorbereitung für Seoul in seinem Sportclub “Dynamo” Berlin mit, “dass gegenwärtig alle Sportlerinnen des Spitzenbereiches der Sektion Turnen erhebliche Schäden vor allem im Wirbelsäulenbereich haben […] “Weiterführung in der bisherigen Form” würde “Dauerschäden” nach sich ziehen:

“Der IM drückte es wörtlich so aus: “Der Staatsanwalt wäre der SV [“Dynamo”] sicher, wenn man bei den XXXXXX der Sportlerinnen nicht auf Verständnis stößt und Regelungen im gegenseitigen Einvernehmen findet.”

Ein konsultierender Arzt habe die Verantwortung abgelehnt, wenn nicht mit den verantwortlichen Trainern Lösungsvorschläge gesucht würden. Letztere würden den Ärzten nicht glauben und “unterstellen den Medizinern mangelnde Risikobereitschaft.” Der Passus wurde mit den denkwürdigen Worten abgeschlossen:

“Formalärztlich wäre eine Weiterführung dieses Trainings eigentlich nicht mehr zu vertreten. […] Nach den bisher vorliegenden medizinischen Erkenntnissen ist unter den heutigen extremen Belastungsbedingungen (sind nicht mehr vergleichbar mit der Zeit von JANZ oder GNAUCK) Veränderungen in den inneren Prozessen der Binde- und Stützgewebe vorgegangen, die über die bisherigen Bilder von Belastungsschäden im Turnen weit hinausgehen. […] Nach Einschätzungen des IM ist davon auszugehen, dass die Grenze der Belastungsmöglichkeiten für den Binde- und Stützapparat erreicht ist.”

In diesem Treffbericht mit dem Arzt wird zum ersten Mal in einer Akte deutlich, dass die Gründe nicht einfach “Überbelastung” sind, wie bisher immer angenommen wurde bzw. Von den Verantwortlichen erklärt wurde, sondern dass die Trainingsmethoden in der DDR offenbar höchste Belastungen in Kombination mit Anabolika und anderen biochemischen Präparaten die Gewebstrukturen verändert hatten. — Giselher Spitzer, Doping in der DDR: Ein offenes Geheimnis (Berlin: Ch. Links, 2000).

[11] „Witzigerweise habe ich als oberster Kopf des DTV dazu keinen offiziellen Bezug gehabt. Da waren nur die involviert, die man nicht rausnehmen kann, einen Arzt kann man nicht rausnehmen, Trainer kann man nicht rausnehmen, Sportler kann man nicht rausnehmen, Schluss. Die wussten also davon. Wir haben natürlich auch Verbandsarzt-Informationen gekriegt. Ich wusste also, dass es Aufbautraining gab. Bei den Mädchen z.B., die waren ziemlich biologisch zurück, da gibt es in der Medizin das Kaiserschema für Magersüchtige und muskelarme Menschen, eine medizinische Kiste, die unter Doping fällt. Da wurde dann quasi das Kaiserschema eingeleitet. Da haben die

auch ein Jahr keine Wettkämpfe gehabt, da waren die so 13, 14. Es hat mir sehr leid getan, wie die Mädels von unseren Trainern im Turnen behandelt wurden. Bei den Männern waren es Kumpels, da ging es. Es gibt keinen Spitzensport ohne Doping, das wird ja heute auch noch so gemacht, ohne DDR.”— Tamara Wewerka, Wende- und Transformationsprozess im Turnen, 1989/1990 (2015).

[12] „Wir haben zum einen Dopingmittel durch die Trainer erhalten, eben in dieser Tablettenform. Mein Trainer sagte mir damals, das sind Mittel, die auch Säuglinge für den Knochenaufbau bekommen. Zum anderen wurden wir natürlich von Ärzten gespritzt oder haben Kaugummis und so weiter bekommen, ich kann aber nicht genau sagen, wo die Dopingmittel dann verpackt waren, das ist mir nicht aufgefallen.“ — „Ich bin nicht daran zerbrochen,” Deutschlandfunk, March 13, 2011