On a November evening in 1981, in Moscow’s Olympic Stadium, a tiny gymnast with freckles and a turned-up nose stood atop the podium as the newly crowned world champion. Olga Bicherova had just pulled off a stunning upset, defeating the reigning Olympic champion with a perfect 10 on vault. She was, officials said, fifteen years old—barely. Her birthday had been October 26, just weeks earlier.

The American gymnasts watching from the stands didn’t believe it for a second. They had reason to be skeptical.

The year before, Bicherova had been left off the Soviet Olympic team because she was too young—not yet fourteen, the minimum age required at the time. Now, just over a year later, she had supposedly turned fifteen—just old enough to meet the new age requirements. The timeline was impossible unless someone had changed her birth year.

And it turned out someone had.

That Night in Moscow

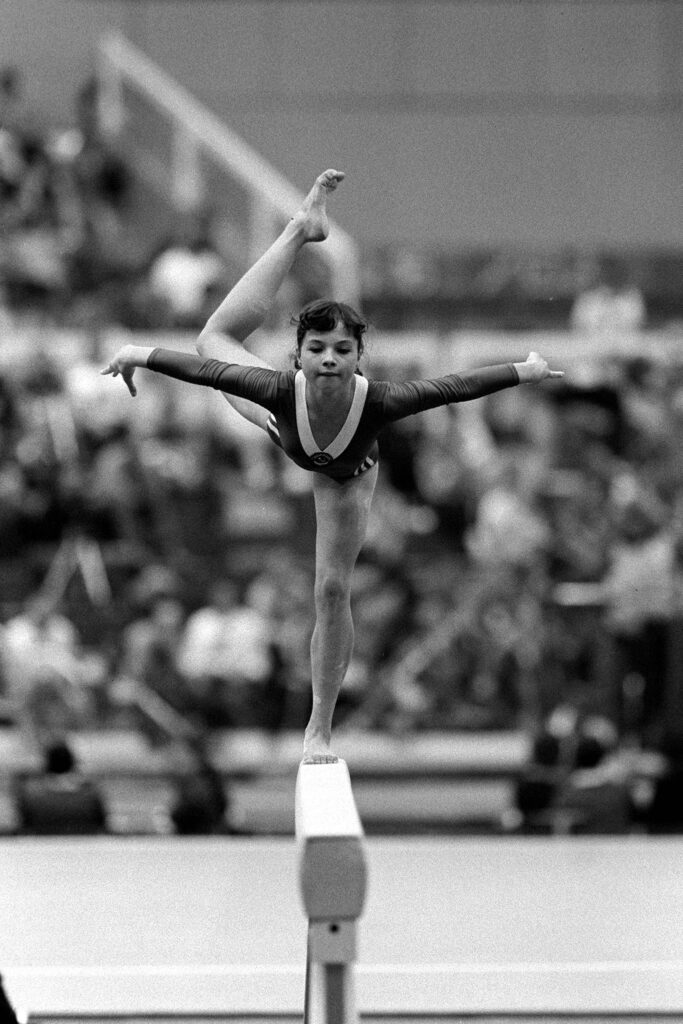

The Olympic Stadium was packed. After the first rotation, Bicherova had moved into the lead with a 9.8 on uneven bars. “The rhythm changed frequently,” Golubev, a Soviet journalist, noted. “That was the ‘highlight’ of her routine.” She stuck the landing, “threw up her nose, waved her hand coquettishly.”

On balance beam, during the second rotation, she grew nervous. Bicherova’s coach, Boris Orlov, would later tell the journalist that, on the morning of the final, Olya had been “especially cheerful, laughing uproariously at her teammates’ jokes.” But beam was different. “She doesn’t have much experience yet,” Orlov noted. She chalked her hands and paced in circles around legendary coach Polina Astakhova. Then she mounted.

“Once she mounted the beam from the springboard, all fears immediately vanished,” the journalist wrote. “What soft, mysterious movements she has! Simply a delight.” She earned 9.75.

On floor exercise in the third rotation, her favorite event, Bicherova performed to a medley from composer Isaak Dunaevsky’s film score for Seekers of Happiness (Искатели счастья). “Not a shadow of embarrassment on her freckled face,” the Soviet reporter observed. Everything worked perfectly. The judges awarded 9.9. After three rotations, she led Filatova by just .075 points.

One event remained: vault. Davydova went first and earned 9.85 on both attempts—solid scores on a difficult vault with two twists in different flight phases. Filatova followed with 9.75.

Now it was Bicherova’s turn. Her signature vault—a Cuervo—earned a 9.9 on the first attempt. Already guaranteed the title, she went again. “Inspired, joyful, she ran again and flew even farther, and the landing was the most precise.”

A perfect 10. The only perfect score during the women’s all-around finals at the 1981 World Championships.

“The competition was still going on, the last participants were finishing their routines, and little Olenka Bicherova had already found herself in the ring of film and photo correspondents,” the Soviet journalist wrote. “From the stands, they managed to pass down programs from this tournament, and they were transferred over the heads of journalists to the champion. She managed to answer questions, give autographs, and laugh heartily, as she knows how to do—just as she laughed this morning, on the day of the final.”

Three Soviet flags rose to the roof of the Olympic Stadium as the Soviet anthem played. The entire podium belonged to the USSR: Bicherova at 78.400, Filatova at 78.075, Davydova at 77.975.

“A remarkable achievement of the Soviet gymnastics school!” the article concluded.

That night, the arena crowned a champion. But while the world applauded a fifteen-year-old, some questioned if she should have been eligible to compete at all.

The Paper Trail

Two and a half years before the World Championships, the paper trail had already begun.

In June 1979, the Soviet sports newspaper Sovetsky Sport reported results from a USSR–East Germany meet in Eberswalde. Second place in the all-around went to “11-year-old O. Bicherova (Moscow)” with a score of 37.65. It was a routine result in a routine meet, the kind of detail that fills sports pages and is quickly forgotten. But it was important. An 11-year-old in 1979 would have been born in 1967 or 1968, depending on her birth month, which would make her thirteen or fourteen in 1981, the year when the age minimum changed to fifteen.

That age continued to track consistently. In February 1981, International Gymnast published Josef Göhler’s report on the Druzhba tournament held the previous October in Varna, Bulgaria. Göhler noted that “Olga, 13, performed” a difficult Cuervo vault, earning a 9.95—the meet’s top score.

Just months later, that thirteen-year-old would be listed as a fifteen-year-old at the World Championships.

“She’s Not 15”

On December 7, 1981, The New York Times published a lengthy investigation under the headline “Rift Over Underage Gymnasts.” The controversy that had been quietly circulating among American coaches and athletes was now public.

The U.S. delegation in Moscow was certain Bicherova was younger than fifteen. Their evidence was based on appearances—not on paper trails. Tracee Talavera, herself only fifteen, was blunt: “Bicherova’s good, but she’s not 15. You only have to look at her.” Two years earlier, Talavera could not compete at the world championships in Fort Worth because she was thirteen—actually too young to compete. Now she watched a girl who appeared even younger than she had been take the all-around title.

Cheryl Weatherstone, a sixteen-year-old competing for Britain who had practiced during the same training periods as the Soviet gymnasts, was more emphatic: “Bicherova’s not a day over 13. She’s so tiny, and just looking at her face, you can see she’s not 15.”

Tom McCarthy, a coach who attended the competition, didn’t mince words: “Undoubtedly, the kid is 13. There is no way this kid is 15 years old.”

The Times article revealed that age falsification wasn’t limited to the Soviets. Béla Károlyi, Romania’s former national coach who had defected to the United States earlier that year, alleged that multiple Romanian gymnasts had also competed illegally. Falsifying passports to change birth dates “happens many times,” he told the Times. He described the pressure from parents and administrators to rush underage gymnasts into international competition.

Soviet officials dismissed the allegations with contempt. Anatoly Gunlenkov, deputy chief of the gymnastics division of the Soviet sports committee, called the charges “trepotnya”—rubbish. He stated firmly that Bicherova was born on October 26, 1966.

Don Peters, the U.S. coach, acknowledged that passport checks had been made by the gymnastics federation in Moscow. Peters admitted Bicherova was among a group of girls “who did not appear to be 15,” but said he had no evidence to dispute her age and cautioned against a hasty indictment. (The U.S. delegation was particularly sensistive to passport checks after Lavinia Agache competed as Ecaterina Szabó earlier in the year.)

Tom McCarthy tried to articulate what was at stake beyond the immediate competition results: “It’s not material to me that Bicherova was younger. She deserved to win, and her scores weren’t inflated. The thing that upsets me is that it’s a negative thing for the sport. What we’re trying to do with the sport is not go with tricks, but refinement. To allow a kid to be 13, 14, or underage, that’s negative. It’s taking away from the older girls who are seasoned, have worked hard, and weren’t allowed to compete.”

The FIG President Disagreed

In April 1982, International Gymnast published an interview with Yuri Titov, the president of the International Gymnastics Federation—the one person whose opinion, in theory, should have settled the matter.

Asked about allegations that Bicherova and other gymnasts were underage, Titov dismissed the concerns as “more gossipy than a real situation.” Then he offered his credentials: “I can give you proof about Bicherova, for the Soviet team, it was not a problem, I know as I stayed between the coaches many times and I was a witness how they chose Bicherova to the team.”

He acknowledged that Bicherova looked like a child but insisted this was meaningless. “Because she is a very little one, she looks like a kid, so many people think she is younger than her age.” He pointed to Japanese gymnasts as an example of athletes who looked young for their age and then invoked a Russian proverb: “We have in Russia a proverb about little dogs, little dogs look like a puppy until near dying.”

Visual evidence, he argued, couldn’t be trusted. What could be trusted? Passports. “We make the control with the passport, what else can we do?” The question was rhetorical. Official documents had been checked and accepted. What more could reasonably be expected?

But passports alone weren’t enough to settle the matter. Titov’s real safeguard was diplomatic trust. Nations had a “moral obligation” to trust one another, he explained. “We must be polite and honor the nation and trust them, it is a moral obligation of any other federation.”

The problem, of course, was that this framework assumed good faith. It required believing that nations wouldn’t falsify the very documents meant to guarantee compliance.

And that’s exactly what happened with Bicherova’s papers.

The Coach Explained

In 1989, the Soviet Union was collapsing. Glasnost had opened space for honest reckoning with the past, and a journalist named Stanislav Tokarev published an article in Ogoniok, a popular magazine, examining the Soviet sports system. In it, he turned to the 1981 World Championships and told the story of what had really happened with Olga Bicherova.

Tokarev’s account was matter-of-fact, almost casual in its revelation of systematic fraud. He noted that the practice of falsifying birth certificates for young gymnasts had begun long ago—in the early 1960s, a coach from Leninsk-Kuznetsky named Innokenty Mametyev had openly admitted to the practice. “Whether it started with them is now impossible to establish,” Tokarev wrote.

Then he turned to Bicherova. After her victory, he wrote, a foreign journalist confronted officials with contradictory start lists showing her real age—one from the Soviet national championships two months earlier, where she was listed as not yet fourteen, another from a recent international youth meet. The officials stonewalled, claiming “typographical errors.”

In 1981, the trend continued. The championships took place in the Olympic Stadium before full stands. The winner was Moscow schoolgirl Olya Bicherova. I have great affection for her; one cannot blame the girl. But after the awards ceremony, a foreign journalist asked her age (according to international rules, participants must be at least fifteen). The answer given was fifteen. The journalist then produced the start list from the national championships two months earlier: Bicherova had not yet turned fourteen. “A typographical error,” the presidium responded. The journalist was not deterred and produced another start list—from a recent international youth meet—with the age printed clearly. “A typographical error,” came the reply.

The paper trail was extensive, all of it contradicting the 1966 birth year claimed in 1981. But documents could only take the story so far. What Tokarev had that the foreign journalists did not was access. At some point after the championships—he doesn’t say exactly when—he sought out Bicherova’s coach, Boris Orlov, whom he described as “a smart and decent man,” and asked how it had all happened. This was Orlov’s response:

“The senior coach called me in and silently handed me her passport with the wrong birth year. That’s how it all started. At least her birth certificate is correct. But how many others have forged ones?”

The confession revealed the chain of command. Someone in the Soviet sports apparatus had procured a passport with a falsified birth year. The senior coach received it and passed it to Orlov without explanation or discussion—the silence itself was the instruction. Orlov understood what was expected and complied. Bicherova’s actual birth certificate remained accurate, a small mercy in an otherwise ruthless sports machine, and Bicherova was no more than a passive victim. As Tokarev wrote, “One cannot blame the girl.”

Tokarev added one more detail about the chairman of the Committee on Physical Culture and Sports: “Word was that [Sergei] Pavlov was furious, but the matter was hushed up; no one was punished.”

Even in a system where age falsification was routine, Bicherova’s case—or more likely the questions from the foreign press in Moscow—had apparently been egregious enough to anger a top official.

The Federation Now Admits Her Age

What happened after the confession is perhaps the most remarkable part of the story: nothing happened for over three decades.

Foreign journalists did not pick up the news. Jim Riordan mentioned it briefly in a 1993 academic article for the Journal of Sport History. Bicherova’s world championship titles remain in the record books, and under today’s Code of Discipline, they cannot be taken from her. Her official biography, repeated in countless sources and interviews, continued to list her birth year as 1966. The fraud had been laundered into history.

But then something changed. The Russian Gymnastics Federation updated Bicherova’s official biography, which states unequivocally that she was “Born on October 26, 1967, in Moscow.” This birth date would have made her just 13 years old when she competed at the 1981 European Championships in Madrid, and only 14 when she won the all-around title in Moscow that November.

More remarkably, the Federation’s own account acknowledges the controversy her age provoked. After her world title, the document notes, “The tiny Soviet athlete – an excellent eighth-grade student – immediately became a legend!” It then adds a telling detail: “At only 14 years old, she looked such a child that many experts demanded her disqualification—for ‘flagrant childishness.'”

But here the narrative takes a definitive turn. The Federation states flatly: “But in fact, there were no grounds for disqualification.”

Indeed, a gymnast cannot be disqualified for “flagrant childishness” or looking too young. But if Bicherova had been born in October 1967, as the Federation now claims, she would not have turned 15 until October 1982—a year after she won the world title. Those were the “grounds for disqualification.” The problem was that no one could prove it because her passport—the only document that mattered for age verfication—had been falsified.

How the Soviet System Worked

There was no single method for age falsification in Soviet gymnastics. Stanislav Tokarev traced the practice back to the early 1960s, when coaches themselves initiated it. Innokenty Mametyev, a coach from Leninsk-Kuznetsky, had falsified birth certificates for his gymnasts. The practice was coach-driven, decentralized, a workaround that individual trainers employed when they believed their athletes were ready before the rules said they could compete.

This pattern continued into the 1980s. Olga Mostepanova described how her coach handled her case: “My new coach made me a new birth certificate, adding a couple of years, so I could compete as a senior.” At age thirteen in 1982, she competed at the USSR Championships and USSR Cup, finishing third at both and earning multiple event medals. “Naturally, I made the national team,” she recalled. Her second-place finish at the USSR Cup in Rostov-on-Don opened the door to the 1983 World Championships in Budapest. “I didn’t think about age then. I trusted my coach.”

Bicherova’s case was different. Her coach did not initiate the falsification. He had been handed a passport with the wrong birth year while her birth certificate remained untouched: “At least her birth certificate is correct. But how many others have forged ones?” In Orlov’s view, there was a hierarchy to the fraud. The fact that Bicherova still had her original birth certificate was an act of mercy—or at least restraint. The lie existed only in her travel documents. The fundamental civil record, the document that would follow her through life, remained true. She would not spend her adult life with an identity based entirely on falsified documents, like a spy or someone in witness protection. Other gymnasts were not so fortunate. For them, the falsification went deeper, starting with the birth certificate itself—the foundational document of identity. In the calculus of Soviet sports, this distinction mattered.

The Weakness in the Rules

Across these different methods—coach-initiated falsification of birth certificates, or top-down falsification of passports only—the Soviet system understood something fundamental about how the governance of international gymnastics actually worked.

The unofficial paper trail didn’t matter. Newspaper reports listing “11-year-old O. Bicherova” could be dismissed as typographical errors. Start lists from national championships showing a gymnast hadn’t yet turned fourteen could be explained away. Visual evidence, the observations of competitors and coaches, the assessments of experienced journalists—all of it was legally irrelevant.

What mattered was the passport. Yuri Titov had made this explicit: “We make the control with the passport, what else can we do?” The FIG’s enforcement mechanism relied entirely on one official identity document. Everything else—no matter how much it contradicted the passport—was inadmissible.

This raises an uncomfortable question about the man who oversaw gymnastics worldwide: How much did Yuri Titov know?

As FIG president, he dismissed concerns about Bicherova as “more gossipy than a real situation.” He invoked a Russian proverb about small dogs looking like puppies until death. He insisted on the moral obligation of nations to trust one another. But he also positioned himself as someone who was deeply embedded in Soviet sports, present at team selections, staying “between the coaches many times” as he put it. He knew “how they chose Bicherova to the team.”

But what did he mean by “how?” Did he know about her passport?

References

Amdur, Neil. “Rift over Underage Gymnasts.” New York Times 7 Dec. 1981.

Göhler, Josef. “International Report.” International Gymnast Feb. 1981.

Golubev, V. “Десять Баллов За Красоту И Полёт!” Sovetsky Sport 29 Nov. 1981.

“Olga Korbut útoda.” Fáklya 20 July 1980.

Sundby, Glenn. “IG Interview with FIG President Yuri Titov.” International Gymnast Apr. 1982.

“Surprising Bicherova Leads Soviets to Gymnastic Sweep.” Winston-Salem Journal 29 Nov. 1981.

Tokarev, Stanislav. “Портреты на Фоне Времени.” Ogoniok, 24, 1989: 30-31

Vasiliev, E. “Успех юных.” Sovetsky Sport 3 June 1979.

Appendix A: Titov’s Quote in Its Entirety

SUNDBY: Many members of the press and delegation made allegations that certain female gymnasts were not the age of 15 for the 1981 World Championships and should not be allowed to compete. Several of the gymnasts mentioned were Agache and Szabo of Romania and Bicherova of the Soviet Union. How does the FIG plan to police this problem in the future to guarantee that the rules of the FIG are followed concerning minimum age?

TITOV: About ages, it seems to me that it is more gossipy than a real situation. I can give you proof about Bicherova, for the Soviet team, it was not a problem, I know as I stayed between the coaches many times and I was a witness how they chose Bicherova to the team. It was really the last day that she was included. As to her size, there are many gymnasts the same, but because she is a very little one she looks like a kid, so many people think she is younger than her age. We make the control with the passport, what else can we do? The official passport, we did it for Championship of the Juniors, and I don’t know how to arrange this question for additional control in the future. We will continue to accept this official document. We also know in gymnastics it is impossible to come up suddenly because they go through the youth competition in the now established European competition so we will know much earlier when a gymnast girl or boy comes into the adult level of competition. We will know them from before. I don’t think this is a problem, maybe only the influence of height of a little girl. I don’t know how to say it, take the Japanese for example, I’m not very tall but during my competition the tallest Japanese gymnast was not much above my shoulder but nobody asked the age of them. But really my friend, my very good friend from Japan, Ahara, competed in my time, but now he looks like 27 or 28, but he is my age. We have in Russia a proverb about little dogs, little dogs look like a puppy until near dying. So I think the control of the official passport and intent to compare results of the youth competition will give us assurance that it will be good. And, of course, we must be polite and honor the nation and trust them, it is a moral obligation of any other federation and it is a moral that must belong to the bodies of federation of the National Federations.

International Gymnast, April 1982

Appendix B: Relevant Sections of the Russian Federation’s Official Bio

Appendix C: The Orlov Confession

A year after the 1980 Games, Moscow hosted the World Gymnastics Championships—the first meeting between those who took part in the Olympics and those who boycotted them. Our ultra-young gymnasts set the tone. The rejuvenation of women’s gymnastics—turning it into a child’s, brutally difficult and dangerous for the female body—had begun long ago. In the early 1960s, the coach from Leninsk-Kuznetsky, I. Mametyev, openly admitted falsifying birth certificates; his wife, who assisted him, used corporal punishment. Whether it started with them is impossible to establish.

In 1981 the trend continued. The championships took place in the Olympic Stadium before full stands. The winner was Moscow schoolgirl Olya Bicherova. I have great affection for her; one cannot blame the girl. But after the awards ceremony, a foreign journalist asked her age (according to international rules, participants must be at least fifteen). The answer given was fifteen. The journalist then produced the start list from the national championships two months earlier: Bicherova had not yet turned fourteen. “A typographical error,” the presidium responded. The journalist was not deterred and produced another start list—from a recent international youth meet—with the age printed clearly. “A typographical error,” came the reply.

Later I asked Bicherova’s coach, Boris Orlov, a smart and decent man, how it all happened. “The senior coach called me in and silently handed me her passport with the wrong birth year. That’s how it all started. At least her birth certificate is correct. But how many others have forged ones?”

They said Pavlov was furious, but the matter was hushed up; no one was punished.

С Игр-80 минул год, и в Москве впервые встретились те, кто участвовал в Олимпиаде, и те, кто её бойкотировал — на чемпионате мира по гимнастике. Тон задавали сверхюные спортсменки. Омоложение женской гимнастики, превращение её в детскую, варварски трудную и опасную для девичьего организма, началось давно. В начале 60-х тренер из Ленинска-Кузнецкого И. Маметьев не скрывал, что подделывает метрички, а жена, ему ассистировавшая, применяет телесные наказания. С них ли пошло — теперь не установить.

В 1981 году процесс развивался. Чемпионат проходил в Олимпийском при полных трибунах. Победила Оля Бичерова — московская школьница. Отношусь к ней с огромной симпатией. Но после награждения зарубежный журналист поинтересовался её возрастом (по международным правилам участницам должно быть 15 лет). Ответили: пятнадцать. Тогда журналист вынул стартовый протокол чемпионата страны двухмесячной давности, где следовало, что чемпионке нет и четырнадцати. «Опечатка», — произвели в президиуме. Журналист достал другой протокол — международных детских соревнований, где возраст проставлен чётко. «Опечатка», — последовал ответ.

Позже я спросил тренера Бичеровой Бориса Орлова, умного, порядочного человека, как всё вышло. «Меня вызвал старший тренер сборной и без слов вручил её загранпаспорт с неверным годом рождения. С того всё и пошло. Но у неё хоть метрика правильная. А сколько у других — поддельных?»

More on Age

One reply on “Too Young to Be a World Champion: How Olga Bicherova Became Fifteen on Paper”

Very fascinating article. I, of course, have long had questions about exactly how old Bicherova was—and it is good to finally have a definitive answer. I imagine the same thing that happened to Orlov also happened with Ilienko’s coach, as her birth date is now listed as 1967 on the Russian Gymnastics website.

I am more curious about the gymnasts who had their actual birth certificates falsified, and if any of them have come forward. I’ve heard reports of certain 80s Soviet gymnasts where this would have had to have been the case, and I wonder if there is any truth in those rumors.