From October 15-19, 1967, Mexico City held the Third Pre-Olympic Gymnastics Meet. It was part of the Little Olympics. (Nowadays, we’d call it the Olympics Test Event.)

Almost all the stars of gymnastics competed. The most notable exceptions: Věra Čáslavská and Mikhail Voronin.

Let’s take a look at what transpired in Mexico one year before the actual Games.

The Backstory | FIG Press Conference | General Impressions | Men’s Results | Men’s Notes | Women’s Results | Women’s Notes | Video Footage

The Backstory on the Little Olympics

On October 18, 1963, in the German resort town of Baden-Baden, the IOC announced that Mexico City would host the 1968 Olympics. The city had finished ahead of bids from Detroit, Buenos Aires, and Lyon.

There were concerns about hosting an Olympics in Mexico City. So, Mexican Olympic organizers hoped to use the Little Olympics as a way of demonstrating that Mexico City was capable of hosting the Games.

Concern #1: Altitude

Altitude: Mexico City is roughly 7,350 feet (2,250 meters) above sea level, and many were concerned about athlete safety.

Problems at the 1955 Pan American Games: Several athletes had collapsed doing those Games. In one incident, the American Lou Jones fell to the track, unconscious, after the 400m race.

“There will be those who die,” announced Finnish trainer Onnie Niskanen (qtd. in Protest at the Pyramid).

The IOC’s Solution: Lengthen the prescribed period allowed for training at high altitudes. According to the Olympic Eligibility Code, athletes were allowed four weeks a year for “special” training at a camp. This was expanded to a total of six weeks.

Concern #2: Disorganization

Here’s how Frank Litsky described things in the October 22, 1967 edition of the New York Times:

There is a word to describe the preparations for next October’s Olympic Games in Mexico City. The word is chaos.

Emphasis added.

The Mexican organizing committee was further along than the Tokyo organizers. The problem was management.

The problem is organizing. There are good men at the top level who know what to do. There are thousands of dedicated volunteers at the lower level ready to carry out orders. But there are precious few people at the middle level to take the orders and see that they are carried out.

Altitude and management were on everyone’s mind as the Olympics approached, and you’ll see it in everyone’s report.

The FIG’s Opening Press Conference

During a press conference, the FIG addressed the world’s concerns about altitude and organization. On Oct. 11, 1967, the newspaper El Siglo de Torreón published notes about the press conference.

Adjusting to life in Mexico

Arthur Gander declared, “The winners will be the gymnasts who have best acclimated to Mexico.”

“Ganarán los gimnastas que mejor se hayan aclimatado en México en estos días”

BTW, if you look at the original article, Arthur Gander’s name is “Antony Gabner.”

Magical Equipment

Ivan Ivancevic “indicated that the facilities in the National Auditorium could be classified as magical and that not even Prague achieved such perfection. The quality of apparatuses is magnificent and meet the Olympic specification.”

“Por su parte, el señor Ivan Cevic [Ivan Ivancevic], Presidente del Comité Técnico de dicha Federación, indicó que las instalaciones del Auditorio Nacional pueden calificarse de mágicas y que ni Praga logró ver instalaciones tan perfectas y que la calidad de los aparatos es magnífica y de acuerdo con las normas olímpicas.”

The Gymnastics Community’s Thoughts on Altitude and Training Conditions

In the December 1967 issue of Modern Gymnast, Jack Beckner, the 1968 U.S. Olympic Team Coach, gave a report about the Little Olympics.

The equipment was great — minus the chalk.

We found the apparatus excellent (Fritzen and Jannson with exception of Japanese Side [Pommel] Horse and Rings) . The only shortcoming was the chalk which was more suitable to bowling than gymnastics.

No problems with altitude or pooping themselves.

We suffered no ill effects from altitude or gastric-enteritis, this latter due to disciplined eating habits.

Note: It’s uncouth to talk about this subject, but food poisoning and traveler’s diarrhea are real problems when competing internationally. At the 1958 World Championships in Moscow, one Japanese gymnast remarked, “Quite likely they would have done even better if no food poisoning” (Yomiuri Japan News, July 10, 1958). At the 1966 “International Sports Week” in Mexico City, Swiss gymnast Max Bruhwiler had gastrointestinal tract issues: “En effet, dans les heures qui précédèrent, le gymnaste zuricois connut des troubles digestifs” (L’Express, Oct. 14, 1966).

Sid Jensen, a Canadian gymnast and student at the University of Michigan, echoed many of the U.S. sentiments in an article from Modern Gymnast, January 1968.

Baby, it’s cold inside.

The building was cool and damp with the evenings especially cool and along with this, it rained incessantly during my entire stay there. For those of you who have back problems, as I have, you can partially overcome this by training in warm clothes as was done by most of the gymnasts.

The Japanese gymnasts somehow built heating into their pants??

Friday morning I discovered the Japanese team warmed up with a central heating system lining in their sweat suits plus woolen wrist bands and gloves. They also used oxygen bottles in training for recovery.

Altitude is a factor, but you adjust within days.

In my first workout, I was astonished upon feeling the effect of dizziness on moving just four mats. A few moves on high bar and I didn’t want to risk a dismount. To do the first half of my optional free exercise routine was as fatiguing as completing the entire routine under normal conditions back home.

By the third day I had adapted to the altitude.

Recovery is hard at altitude.

During the competition no one complained of dizziness. There wasn’t an abnormal number of gymnasts with landing problems with the best performers still sticking their landings. Although the altitude did not hinder free exercise performances noticeably, everyone did admit that it took twice the time to recover after the completion of a routine. Don’t put off running a little during the week.

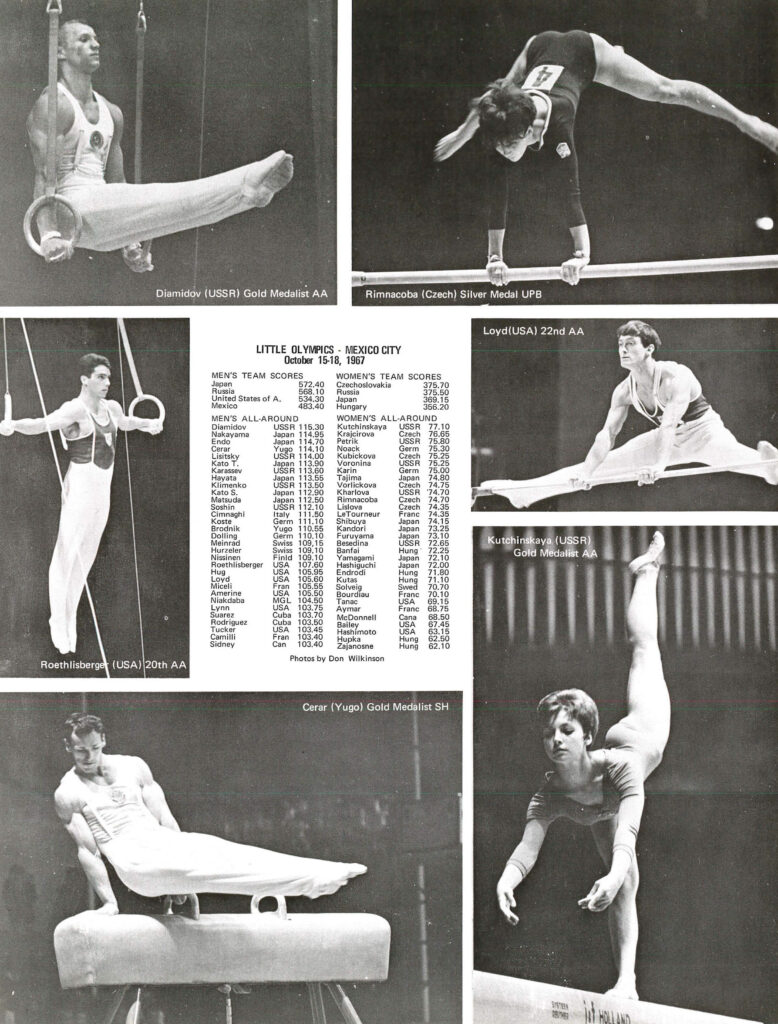

The Men’s Results

Team Competition

| Country | Score |

| 1. Japan | 572.40 |

| 2. Soviet Union | 568.10 |

| 3. USA | 534.30 |

| 4. Mexico | 483.40 |

Men’s All-Around – Top 10

| Name | Country | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 1. Diomidov | URS | 57.45 | 57.85 | 115.30 |

| 2. Nakayama | JPN | 57.85 | 57.10 | 114.95 |

| 3. Endo | JPN | 57.35 | 57.35 | 114.70 |

| 4. Cerar | YUG | 56.50 | 57.60 | 114.10 |

| 5. Lisitsky | URS | 57.05 | 56.95 | 114.00 |

| 6. Kato Takeshi | JPN | 56.75 | 57.15 | 113.90 |

| 7. Karasev | URS | 56.85 | 56.75 | 113.60 |

| 8. Hayata | JPN | 56.65 | 56.90 | 113.55 |

| 9. Klimenko | URS | 56.90 | 56.60 | 113.50 |

| 10. Kato Sawao | JPN | 56.50 | 56.40 | 112.90 |

Optional Scores & Totals: Modern Gymnast, Nov. 1967

Floor Exercise

| Name | Country | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 1. Nakayama | JPN | 9.70 | 9.60 | 19.30 |

| 2. Kato Sawao | JPN | 9.60 | 9.55 | 19.15 |

| 2. Diomidov | URS | 9.55 | 9.60 | 19.15 |

Side Horse / Pommel Horse

| Name | Country | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 1. Diomidov | URS | 9.55 | 9.70 | 19.25 |

| 2. Cerar | YUG | 9.40 | 9.70 | 19.20 |

| 3. Karasev | URS | 9.40 | 9.55 | 18.95 |

Still Rings

| Name | Country | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 1. Nakayama | JPN | 9.80 | 9.75 | 19.55 |

| 2. Hayata | JPN | 9.65 | 9.80 | 19.45 |

| 3. Lisitsky | URS | 9.70 | 9.75 | 19.45 |

Long Horse Vault

| Name | Country | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 1. Endo | JPN | 9.50 | 9.70 | 19.20 |

| 2. Matsuda | JPN | 9.45 | 9.65 | 19.10 |

| 3. Klimenko | URS | 9.40 | 9.55 | 18.95 |

Parallel Bars

| Name | Country | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 1. Nakayama | JPN | 9.70 | 9.90 | 19.60 |

| 2. Diomidov | URS | 9.75 | 9.70 | 19.45 |

| 3. Hayata | JPN | 9.65 | 9.65 | 19.30 |

High Bar

| Name | Country | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 1. Nakayama | JPN | 9.70 | 9.75 | 19.45 |

| 2. Endo | JPN | 9.70 | 9.70 | 19.40 |

| 3. Diamidov | URS | 9.60 | 9.75 | 19.35 |

| 3. Kato Sawao | JPN | 9.65 | 9.70 | 19.35 |

| 3. Kato Takeshi | JPN | 9.65 | 9.70 | 19.35 |

Note: There was also a Little Olympics in 1965, which Menichelli of Italy won.

Note #2: And there was another Little Olympics (sometimes called the International Sports Week) in 1966, which Wilhelm Kubica of Poland won after Voronin fell on high bar. Voronin went on to win 5 gold medals during the event finals.

Note #3: The 1966 Little Olympics was rough:

Trouble at the Arena Mexico delayed the gymnastics when lights failed and when France’s top performer, Christian Deuza, fell on his neck during his performance on rings.

The Yomiuri, Oct. 14, 1966

Notes on the Men’s Competition

The 1968 compulsories were used.

“Además, se establecerán los ejercicios obligatorios que serán reglamentarios en los Juegos Olímpicos de 1968 para que todos conozcan el grado de dificultad.”

El Siglo de Torreón, Aug. 22, 1967

Most of the U.S. gymnastics community’s commentary was about compulsories.

I won’t bore you with the details about which moves were tricky, but the U.S. contingent was concerned about compulsories for good reason. American Robert Lynn had the highest compulsory score: 53.50. That was 4.35 behind Nakayma’s compulsory score (57.85).

Fred Roethlisberger had the highest all-around ranking for the U.S. men (20th), and his compulsory score was even lower: 52.60.

Voronin injured his shoulder in training.

The Soviet team was unsure if they would compete in the team competition without Voronin. They decided to do so, and after compulsories, they were 1.6 points behind the Japanese team.

Le forfait du champion du monde Mikhail Voronnie, qui s’est blessé à une épaule à l’entraînement, a grandement handicapé les Soviétiques au cours de la première journée des épreuves de gymnastique. Après avoir hésité à le faire en raison de la défaillance de Voronine, les Russes ont tout de même décidé de concourir pour le classement par équipes. Après les exercices imposés, ils comptaient cependant 1,6 point de retard sur les Japonais, ce qui leur enlève pratiquement toute chance cle succès

L’Express, Oct. 18, 1967

The Japanese gymnasts went overtime on floor during their optional routines

Les « libres » commencèrent mal pour les Japonais qui, dans les exercices au sol, dépassèrent tous le temps et furent ainsi pénalisés.

L’Express, October 20, 1967

Nakayama messed up his pommel horse routine, costing him the gold.

Mais c’est au cheval-arçons que Nakayama laissa échapper la victoire en ratant totalement son exhibition.

L’Express, October 20, 1967

And he had a funny comment about it.

“I have never done so badly on the pommeled horse,” Nakayama said. “I am going to go home and practice all next year so that I can get a minimum of 9.2 in the Olympics.”

Yomiuri, Oct. 20, 1967

In fact, the entire Japanese team struggled on pommel horse.

Les Japonais ont d’ailleurs été très faibles à cet engin et un seul des leurs, Kato, participera à la finale individuelle.

L’Express, October 20, 1967

Nakayama wasn’t sure if he would make the Olympic team.

“It is much harder to win competition in Japan. Japan has so many good gymnasts that I can’t be sure I’ll be coming back for the Olympics next year.”

Yomiuri, Oct. 21, 1967

The organizers had problems with circulating the right scores — one year before the Čáslavská/Petrik debacle.

Kato [Takeshi] had some criticism for the Mexican organizers of the gymnastic competition.

“They made many mistakes in the scoring, especially during the first day of the men’s competition,” he said. “When the competitors don’t know their own scores, it makes things very difficult for them. It is most important to announce the correct points. I hope next year Mexico will have an electric scoreboard.”

At first, officials said Akinori Nakayama had won the gold medal with 19.5 points, which would have bettered the Olympic record of 19.45 set in Tokyo by Franco Menichelli of Italy. But later officials switched Nakayama’s point total to 19.350, saying the previous point totals distributed to reporters for the competitors was incorrect.

The scoring sheet had incorrectly given Nakayama 9.8 previous points instead of the 9.65 he should have received.

The difference deprived Nakayama of the Olympic record.

Yomiuri, Oct. 21, 1967

Skills that stood out to the U.S. team:

Cerar of Yugoslavia: “His Stalder shoot with a 1/2 turn to forward giants was one of the best executed Super C moves.

Dolling or Köste of East Germany: “One did a free hip, hop to reversed grip, immediate stoop through and shoot to “Takamoto” on the H. Bar.” (The other isn’t quite sure which one did it.)

*In Modern Gymnast, Jack Beckner, the team coach for the U.S., didn’t indicate which gymnast performed that sequence.

Lisitsky and Soshin of the USSR: “Mounted the side horse with back loops on the end.”

Klimenko of the USSR: “demonstrated unusual ability and daring on Diamodov, stutz to handstand and dismounting with ‘back somi full twist'”

The Women’s Results

Team Competition

| Country | Score |

| 1. Czechoslovakia | 375.70 |

| 2. Soviet Union | 375.50 |

| 3. Japan | 369.15 |

| 4. Hungary | 356.20 |

Even without Čáslavská, the Czechoslovak team beat the Soviet team.

The All-Around – Top 10

| Name | Country | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 1. Kuchinskaya | URS | 38.40 | 38.70 | 77.10 |

| 2. Krajčírová | TCH | 38.20 | 38.45 | 76.65 |

| 3. Petrik | URS | 38.00 | 37.80 | 75.80 |

| 4. Noack | GDR | 37.50 | 37.80 | 75.30 |

| 5. Kubičková | TCH | 75.25 | ||

| 5. Voronina* | URS | 75.25 | ||

| 7. Janz | GDR | 37.60 | 37.40 | 75.00 |

| 8. Tajima | JPN | 74.80 | ||

| 9. Vorlíčková | TCH | 74.75 | ||

| 10. Karlova | URS | 74.70 | ||

| 10. Řimnáčová | TCH | 74.70 |

Totals: Modern Gymnast, Nov. 1967

Vault

| Name | Country | Total |

| 1. Kuchinskaya | URS | 19.40 |

| 2. Krajčírová | TCH | 19.316 |

| 3. Janz | GDR | 19.283 |

Uneven Bars

| Name | Country | Total |

| 1. Janz | GDR | 19.433 |

| 2. Řimnáčová | TCH | 19.250 |

| 3. Kuchinskaya | URS | 19.233 |

Balance Beam

| Name | Country | Total |

| 1. Kuchinskaya | URS | 19.458 |

| 2. Krajčírová | TCH | 19.150 |

| 3. Noack | GDR | 19.133 |

Floor Exercise

| Name | Country | Total |

| 1. Kuchinskaya | URS | 19.508 |

| 2. Krajčírová | TCH | 19.408 |

| 3. Petrik | URS | 19.395 |

Note #1: Čáslavská won the 1966 Little Olympics (sometimes called the International Sports Week). Kuchinskaya finished second.

Note #2: The East Germans didn’t compete at the 1966 Little Olympics because of a naming convention.

The East Germans boycotted the women’s gymnastics competition in the Little Olympics today because they insist they’re a country and not a direction.

They didn’t like it because they were listed on the program as “Alemania Del Este,” Spanish for East Germany.

…

Their male gymnasts showed up Wednesday at the Arena Mexico, where the events were being held, looked at the program, saw “Alemania Del Este” and refused to compete.

Today the women didn’t show up at all.

Yomiuri, Oct. 15, 1966

Notes on the Women’s Competition

The U.S. gymnastics magazines didn’t write about the women’s competition. To get a partial picture of what happened, I had to turn to the Mexican newspaper El Siglo de Torreón, the East German newspaper Neues Deutschland, and the Yomiuri, an English-language newspaper out of Japan.

Even before the competition started, Kuchinskaya was making a name for herself in Mexico.

On February 2, 1967, the Mexican newspaper El Siglo de Torreón printed a profile of her. Here are a few notes:

- She was fearless: “A [Kuchinskaya] nada temía, ni a los saltos más atrevidos ni a los movimientos altamente complicados; su valentía y perseverancia, así como sus indiscutidas facultades la han hecho una figura mundial de gimnasia.”

- She was a fantasy come to life: “Constituye todo un espectáculo, de una fantasía hecha realidad por la mímica y precisión de sus movimientos”

Spoiler: During the 1968 Olympics, Kuchinskaya would be called “La Novia de México” (“The Bride of Mexico”).

As for WAG at the Little Olympics… Hardly any of the 9,250 seats were empty during the women’s compulsories.

Yes, during compulsories.

Sonntag abend fand man im National Auditorium, einer riesigen Halle, die das Jahr über ebenso viele Ausstellungen beherbergt wie Eisrevuen, kaum einen der 9250 Sitzplätze leer. Die 37 Turnerinnen aus zehn Ländern hatten bei ihrem Pflichtprogramm diese große Zuschauerzahl angelockt.

Neues Deutschland, Oct. 17, 1967

Marianne Noack fell on beam but repeated the compulsory routine to get a 9.3, and the crowd “cheered with genuine joy.”

Als Marianne dann ihre Wiederholung so großartig turnte, daß sie mit 9.3 Punkten noch um ein Zehntel besser war als Karin Janz, jubelte die Halle vor ehrlicher Freude.

Neues Deutschland, Oct. 17, 1967

Note: Starting in 1968, gymnasts were no longer allowed to repeat compulsory routines.

When the judges gave Marianne Noack a low 9.5 on compulsory bars, the crowd let the judges know that they weren’t pleased.

Und nur als Marianne Noack am Stufenbarren mit 9.5 Punkten vielleicht ein wenig knapp bewertet wurde, gab es leisen Aufruhr, so, als wollte man den Kampfrichtern zu verstehen geben, daß man sich durchaus ein Urteil bilden könne.

Neues Deutschland, Oct. 17, 1967

My thought bubble: Pay attention to the references to cheering. We are seeing a lot of references to the crowd already in 1967. During the 1968 Olympics, the audience’s reactions will play an important role.

Without Čáslavská, the Czechoslovak team had to rely on Krajčírová.

Largely responsible for the Czech’s* overtaking Russia was 18-year-old Marianna Krajčírová. Her personal total was 38.45, including a nearly perfect 9.80 for floor exercises.

Yomiuri, Oct. 19, 1967

*I believe that Krajčírová is Slovak — not Czech.

But Krajčírová almost didn’t compete due to an elbow injury.

[Marianna] injured her elbow Sunday during compulsory exercises and had to have it X-rayed to see if she could continue. On Sunday her coach said that if [Marianna] had to pull out, Czechoslovakia would not have enough girls left to continue on the team competition.

Yomiuri, Oct. 19, 1967

Somehow, Noack ended up with Petrik’s bronze medal, but she later gave it to the rightful owner.

Als man im National Auditorium die Siegerinnen im Turnen aufrief, war auch Marianne Noack dabei. Daß sie es war und nicht Karin Janz, war schon Überraschung genug, aber jeder, der mitgerechnet hatte, wußte obendrein, daß nur Larissa Petrik (UdSSR) für die Bronzemedaille in Frage kam. Das Publikum aber jubelte. Es hatte die beiden DDR-Mädchen vom ersten Augenblick an in ihr. Herz geschlossen, und als Marianne auf das Siegerpodest stieg, formierte sich gar ein Sprechchor auf den Rängen; Bravo Republica Democratica Alemana! Eine Stunde später berichtigte man das Resultat, und Marianne wird die Medaille zurückgeben, so daß sie Larissa bekommt, der sie zusteht. Ihr eigener vierte Platz ist ihr ohnehin Erfolg genug.

Neues Deutschland, Oct. 19, 1967

In her first year as an international elite, 15-year-old Janz won gold on the uneven bars, defeating the Soviet Union’s top gymnasts.

That was a big deal. Only Čáslavská was missing.

Ihren bisher größten Internationalen Erfolg errang die 15jährige DDR-Turnerin Karin Janz bei den Finalkämpfen an an den Einzelgeräten während der Internationalen Sportwochen in Mexiko-Stadt. In einem äußerst leistungsstarken Feld — es fehlte nur die CSSR-Europameisterin Vera Caslavska – bezwang sie am Stufenbarren sowohl die Weltmeisterin Natalja Kutschinskaja als auch die Tschechoslowakin Bohumila Rimancova und eroberte sich mit 9.833 Punkten unter dem Jubel der begeistert mitchenden 12000 Zuschauer im Auditorium Nacional der künftigen Olympiastadt die Goldmedaille. Einen gleichfalls beachtlichen dritten Rang schaffte Marianne Noack (DDR) am Schwebebalken, wo sie Larissa Petrik UdSSR) auf Platz vier verwies.

Neues Deutschland, Oct. 21, 1967

Competition Footage

In this video, you can see Kuchinskaya nail her vault, and you can see how Janz swings on bars. The power of her clear hip into her high-flying full-twisting hecht was remarkable.

And you can watch Marianna Krajčírová’s floor routine here:

2 replies on “1967: Gymnastics at the Little Olympics in Mexico City”

Do you have any other information about the 1967 Little Olympics as a whole, not just gymnastics? Any place I can find resources? I would like to learn about it, and find precious little information online. Thank you.

Very great article. I unquestionably adore this Internet site. Thanks!