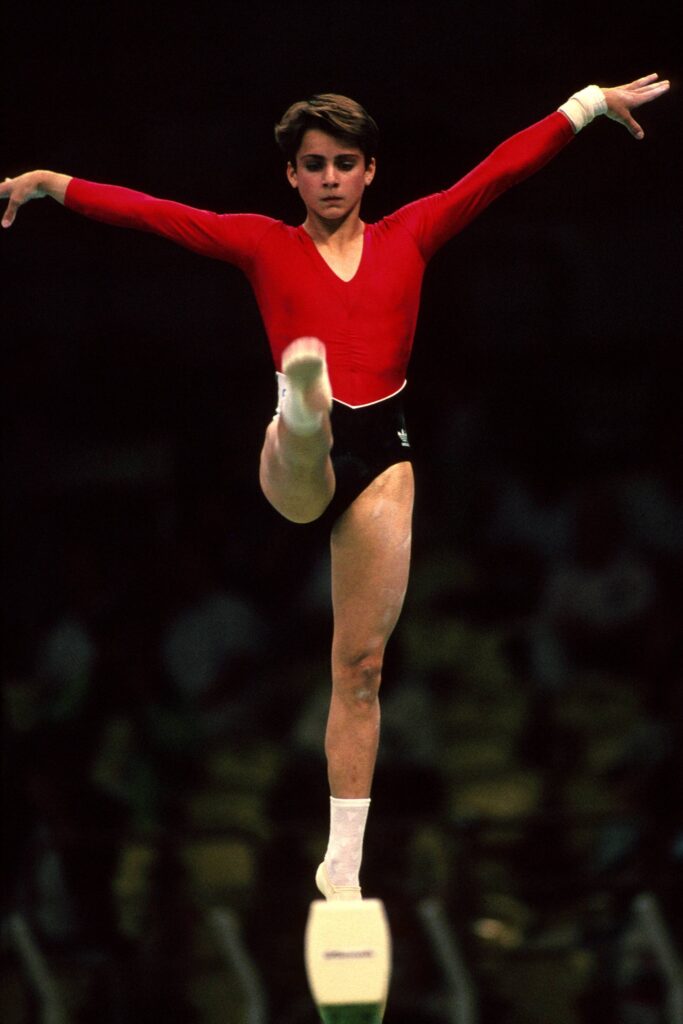

Rotterdam, October 1987. Dörte Thümmler stood before the uneven bars in Amsterdam’s Ahoy Hall, knowing what she had to do. Her teammate Gabriele Fähnrich, the reigning world champion, had only just returned to competition after a long injury layoff and had fallen during compulsories. Now the fifteen-year-old Berliner—just 1.47 meters tall and 36 kilograms—was suddenly East Germany’s best hope for gold. She executed her routine flawlessly: the Tkatchev, the Deltchev, the toe-on front with a half turn, landed with just a small shuffle backward. When the score appeared—a perfect 10—she had won the world championship title on uneven bars, sharing the gold with Romania’s Daniela Silivaș. Dutch journalists were stunned. “Thümmler?” one said. “In a poll of favorites, her name would not have appeared on a single ballot.” In claiming this title, she continued a long tradition that included Maxi Gnauck and Fähnrich herself.

Thirty years later, Dörte Thümmler spoke publicly for the first time about what that victory had cost. At a press conference held by the Doping Victims Assistance Association in April of 2018, she stood alongside other former gymnasts, all of them bearing similar damage. For eight years by that point, she had been unable to work, living on a full disability pension. Medical specialists at Berlin’s Charité hospital had diagnosed her with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. She had only thirty percent of the strength typical for people her age. She was forty-six years old.

What Thümmler and the others revealed that day was something far worse than simple overtraining. Across East Germany’s gymnastics program, young girls had been fed into a system that treated them as experimental subjects rather than children. They trained seven hours a day, six days a week. They lived in boarding schools separated from their families. They were told the pills were vitamins. And when their bodies inevitably broke down—often before they even reached adulthood—they were left to live with permanent disabilities.

The System She Couldn’t Escape

Dörte Thümmler never wanted to be a gymnast. According to interviews published in German media, at four years old, her mother took her ice skating, and she took to it immediately, gliding across the ice with joy. But her mother, Karin, had been a gymnast herself—one who never achieved great success—and she had other plans for her daughter. Dörte was enrolled in a Berlin sports kindergarten, which fed directly into the training halls of SC Dynamo Berlin in Hohenschönhausen. By eight, she had moved into the boarding school. For the better part of a decade, her life followed an unvarying pattern: training from Monday morning until Saturday at 1 PM, a single day at home, then back to the dormitory Sunday evening.

When Dörte was eleven, she told her mother that she wanted to quit. What followed was a coordinated campaign to break her resistance. Individual meetings with various trainers, physiotherapists, and officials culminated in a conference room session where they all sat before her and told her she couldn’t stop. Her parents, deeply embedded in the sports system themselves, did not support her wish to leave. Her stepfather, Manfred Thümmler, was the medical director of SC Dynamo Berlin’s sports medicine department and, from 1974 onward, a member of the so-called “Working Group for Supporting Means”—the bureaucratic euphemism for the state’s doping program. In the 1999 Berlin doping trial, he would be charged with complicity in bodily harm, though the case was ultimately dismissed.

The pressure she faced mirrored the pressures shaping the entire coaching culture. Contemporary reports captured what this looked like from the inside. Coaches, in particular, were often the ones pressing for more permitted and banned “supportive means” for their athletes. One such report came from Dr. Manfred Höppner—IM Technik in the Stasi files, deputy head of the Sports Medical Service, and chair of the “Working Group on Supporting Means.” In a meeting note dated November 6, 1975, he wrote: “In sports medicine support, they apparently see the only possibility for further performance improvements at present. This was evident even at the Spartakiade, where a large part of the athletes, even those still of school age, had already been ‘fed up’ [i.e. given substances]. The informant particularly emphasized the activities of the trainers, who demand and largely succeed in getting the doctors to use all permitted and prohibited means. Ultimately, their bonus depends on it, which is substantially higher than that of the doctors.”

The dynamics the informant described—coaches competing, unrealistic demands, and escalating pressure—were the same forces that structured Thümmler’s training. After a coaching change, Thümmler entered what she later described as a terrible period marked by humiliation, injury, and fear. The rivalry among Dynamo’s coaches was fierce—each fought for results, each a cog in a vast system that measured worth in medals. That pressure flowed downward, from federation officials to the trainers, and from the trainers to the girls under their control. One federation coach once stood before the gymnasts and shouted, “You’re destroying my future!” Everyone in the hall heard it—the athletes, the other coaches, the doctors, the physiotherapists, the choreographers, the officials standing at the edges. When the Meistertrainer lost his temper, as he often did, the shouting echoed through the gym. Everyone watched, but no one said a word. The silence was part of the system.

The Chemistry of Control

The chemical compounds came in various forms. According to accounts from former athletes, there were protein pralines and chewing gum—treats that seemed like rewards in a system where eating was rigidly controlled and monitored. The young gymnasts were delighted to receive them, not knowing they contained performance-enhancing substances. There were Dynvital and other packets whose purpose was never explained.[1] The regular blood tests, lactate measurements, and urine samples were presented as routine medical monitoring, not as tracking for the metabolic effects of systematic doping.

Anabolic steroids in women’s gymnastics served a dual purpose. Like in other sports, they aided recovery, allowing athletes to train harder and more frequently without their bodies breaking down—or at least, not as quickly. But in gymnastics, figure skating, and similar sports emphasizing small bodies capable of complex aerial maneuvers, the hormones had an additional function: growth suppression. There was even a medical term for the procedure: the “Kaiser-Schema.”

Developed by Professor Kaiser, a senior physician at the Charité hospital, the treatment was intended for developmental disorders affecting bone and cartilage growth. In East Germany, it was frequently prescribed to gymnasts, where—whether inadvertently or by design—it produced short-term performance advantages. When anabolic steroids are administered before puberty, they cause the growth plates at the ends of long bones to close prematurely, stopping vertical growth. One of the most common drugs used in East German gymnastics was Oral-Turinabol (OT), a small, sky-blue tablet manufactured by Jenapharm. The package insert for the drug noted clearly: “In children, accelerated sexual and bone maturation as well as premature growth cessation can be observed.” But that warning was added only after the fall of the socialist state. During the operational years, neither the athletes nor their parents were informed of the risks.

In addition to OT, the systematic administration of STS 646 to elite gymnasts was part of East Germany’s doping regimen. Though illegal under East German law, the drug was given to the women’s Olympic and national teams between 1979 and 1981, and likely beyond. Stasi files reveal the lengths to which GDR scientists went to ensure negative tests, establishing procedures to cycle athletes off drugs before competitions and testing athletes before they left the country. Even so, the system sometimes failed. In one September 1988 incident report—just before the Seoul Olympics—officials complained about an SC Dynamo Berlin gymnast who “strictly resisted” providing a urine sample for testing, causing a ninety-minute delay. The gymnast was Dörte Thümmler. Decades later, discovering documentation of this act of resistance brought her grim satisfaction—proof that she had tried to fight back, even when every attempt felt futile at the time.

Beyond anabolic steroids, the East German doping machine employed unauthorized neuroleptics. According to biochemist Wilhelm Schänzer of the Biochemical Institute at the German Sport University Cologne, these were substances that the body can produce naturally, but which were administered in large quantities from external sources. The goal, as Schänzer explained to German media, was to make athletes more aggressive, more combative, better able to handle stress. The problem was the unpredictability: “How this polymedication works, what the side effects are, you can’t predict that, you can only observe it perhaps—these are experiments on humans.”

In other words, what happens when the chemistry of the brain becomes another field of state-controlled experimentation? The scientists didn’t always know.

The Human Corpses in Frankenstein’s Laboratory

Heike M. had been a rising star in East German gymnastics. As a young athlete, she became the GDR school champion on floor exercise and competed internationally, including at competitions in Cuba. She was a contemporary of Maxi Gnauck, who would go on to win Olympic gold in Moscow in 1980. In fact, Heike was among those training for the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, but her body betrayed her before she could make it.

When Der Spiegel investigated her case in 2015 under the headline “Frankenstein’s Laboratory,” Heike M. was fifty-two with the medical file of a construction worker: extensive degeneration of the cervical and lumbar spine, a torn triceps tendon, elbow ossification, hip joint inflammation, sudden headaches, shoulder and muscle pain, and depression. She taught school, though her health often made it difficult, and preferred not to use her full name—she did not want pity from students or colleagues. From seventh grade onward, she had never been pain-free for a single day. Her gymnastics career ended at sixteen when her spine could no longer withstand the strain. A chief physician’s assessment in 1982 rated her permanent physical damage at twenty percent.

She hoped for a normal life. She married a weightlifter who had also been broken by the system—his torn knee ligaments ended his Olympic prospects. She studied, became a teacher, and had two children. But the pain never stopped. As the years passed, it grew harder to maintain her teaching duties, and even ordinary workdays became unpredictable, governed by what her body could or could not endure.

When she applied for disability benefits, the office rejected her claim. Her case went to social court in Cottbus, where the judge appointed molecular biologist Werner Franke to evaluate her condition. Franke, from the German Cancer Research Center, had spent over forty years studying physical overstrain in sports, with particular expertise in doping.

What Franke found in Heike M.’s archived medical records revealed the full scope of the medical experimentation. East German sports doctors had systematically manipulated her growth. First, they gave her anabolic steroids to keep her small, and then later, after her career ended, they injected her with growth hormones harvested from human corpses to restore her to normal height. After her retirement in July 1979, she was sent to Kreischa in Saxony, a special clinic for elite GDR athletes. There, for at least six weeks, she received injections of Sotropin H, a growth hormone manufactured by VEB Arzneimittelwerk Dresden from the pituitary glands of human corpses—an intervention that could have led to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a rare and often fatal brain disorder.[2]

The treatment worked as intended. Kind of. After stopping the anabolic steroids and taking the growth hormone, Heike M. grew ten centimeters in a single year. But her musculoskeletal system could not withstand this forced transformation. The result was damaged joints, causing lifelong pain. Franke determined her disability level at a minimum of fifty percent.

As part of his investigation, Franke interviewed pathologists who had worked in East Germany during that era. According to Der Spiegel, they said they had wondered at the time why their preparators always obtained permission to remove and retain pituitary glands from corpses. Now they understood: the glands were being harvested for pharmaceutical production, part of an elaborate system to first stunt athletes’ growth, then attempt to reverse the damage once their competitive usefulness had ended.

When Saying “No” Was Impossible

Today, the Berlin Doping Victims Assistance Association hears from many of those athletes. Former gymnasts describe chronic pain in their spines, shoulders, feet, and hips. Some experience masculinization; many struggle with depression. These are the long shadows cast by the practices once hidden behind institutional walls.

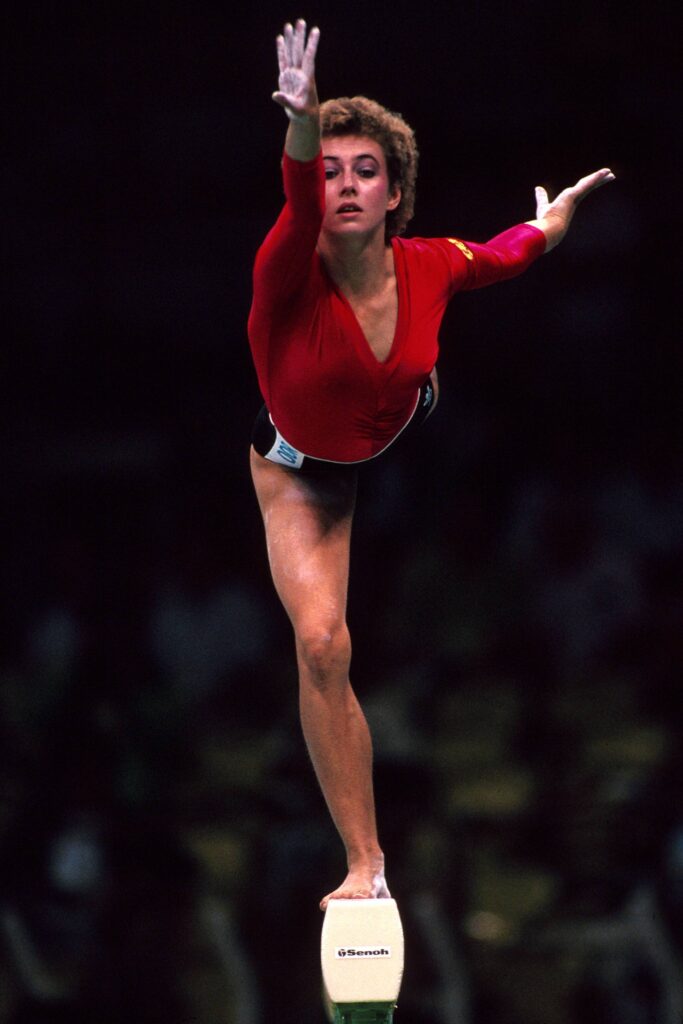

Among the former gymnasts who have sought help is Gabriele Fähnrich, the world champion on uneven bars in 1985 and Olympic bronze medalist in 1988. When she won gold, she didn’t even know about one of her injuries. Standing in front of a hotel mirror, drying her hair, she noticed a bulge protruding from her upper arm. When she felt further down, there was a hole where she could press through to the bone. As she recalled the exchange, the federation doctor’s response was: “Oh! So you finally discovered it. You have a muscle fiber tear.”

The knee pain started in fifth grade. Her memories consist of being constantly injected, given pills for cartilage repair, injected again and again, always in pain. With a daily training load of up to eight hours on bars, beam, floor, and vault, the injuries were inevitable. In interviews, Fähnrich described how those around her treated pain as an inconvenience that had to be suppressed. The answer was always pills and injections.

One of those pills was the most familiar of all, and it came with specific instructions. As Fähnrich recounted to reporters, she was called to her coach’s room and instructed that she would receive a tablet—a vitamin pill, they said—that would be good for her. But she shouldn’t tell her parents and shouldn’t discuss it with her teammates. “Then you took the pill, whatever it was,” she recalled. “It was all done in trust. Ultimately, you’re like a big family there. There was trust in that.” When she saw an article about GDR doping in the early 1990s with a picture of the packaging, recognition hit: “We got those, too! And that was doping! I was pretty shocked by that. Actually speechless.”

She wanted to quit many times, but it was impossible. Her future was not hers to decide. She belonged to the national team from an early age. Despite injuries, the GDR sports leadership didn’t hesitate to deploy her at the 1988 Olympics even though she should have stopped due to her condition. As she told Deutschlandfunk: “I had constant pain, but they didn’t accept that.” Officials held a two-hour lecture, threatening that she would be discharged in dishonor and would receive no benefits. Out of desperation, she finally said yes.

After winning bronze with the team in Seoul, Fähnrich ended her athletic career in 1988, one year before the fall of the Berlin Wall. She received a two-year apprenticeship as a cosmetician, being handed the key to an apartment, and receiving money in two installments from a man at the State Security sports forum in Berlin.

It took years before Fähnrich turned to the Berlin Doping Victims Assistance Association and found the strength to speak about her suffering. Two years before her 2018 interview, an expert assessment formally recognized her as a doping victim. The conditions she lives with trace a clear line back to her time in the system: persistent pain radiating through her back and knees, high blood pressure, and post-traumatic stress disorder. The pressure of those years still shadows her nights—she has not slept peacefully in three decades—and her daily life has been constrained for just as long. The compensation she ultimately received, 10,500 euros, offers little relief; it can neither undo the physical damage nor ease the psychological burden she carries.

Living With the Damage

Dörte Thümmler stopped competing in 1988, but the system’s effects on her body and her future did not. After months in the sports medicine facility in Hohenschönhausen trying to rehabilitate her damaged back, it became clear she would not return to the training hall. She wanted to become a choreographer—the daily ballet classes had been the only part of her gymnastics career that held positive memories—but her back problems made that impossible.

She trained instead as a restaurant specialist. When her first son was born in 1995, she was twenty-three years old. Three years later, she suffered her first nervous breakdown and spent months in a psychiatric clinic. Her greatest fear during this time was for her child’s development. Over the years, she came to understand that she had internalized the lessons of elite sport too well: push beyond all limits, give everything until collapse, because that was the only way she had ever known to function.

She once tried to attend a gymnastics competition with a friend. She could not bear it. Perhaps the memories were too painful. At a training camp in Kienbaum, she once stood on the balance beam and said she would not continue. The trainer kicked her feet out from under her so hard that she fell lengthwise onto the apparatus. She was a child. He was an adult. Everyone in the hall watched. No one intervened.

In interviews with German media, Thümmler said she had never been allowed to feel pride in her accomplishments. Pride was considered dangerous—it could lead to complacency—so it was systematically extinguished. The system demanded obedience, not joy. Winning, she explained, had never been her motivation. She only wanted not to be yelled at, to be left in peace. As she put it, it sounded strange even to her, but she was probably too talented for her own good, because the sport was never something she chose.

Somehow, after her second son was born in 2008, she found her way back into the gym through parent-child gymnastics classes. She obtained a coaching certificate and finally achieved her dream. She began teaching children dance and choreography. But unable to moderate her efforts in the way the system had never taught her, her body broke down again.

By 2018, she had been on full disability pension for eight years, unable to work. Diagnosed with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, she—a former world champion and Olympic medalist—had only thirty percent of the strength typical for people her age. If she failed to manage this limited energy with extreme care, days or weeks of whole-body pain would follow. Some treatments would help, but they were not covered by the pension or social assistance.

At forty-six, Dörte Thümmler had given her entire childhood and adolescence to a system that gave her little in return except for damaged bones and chronic illness. She had no self-determined life in sport, and decades later, she remained far from having one in its aftermath. The GDR’s high-performance sports system made decisions for her when she was a child, and she continued living with those decisions every day.

When Silence Ends

In the years following German reunification, accountability for the GDR’s doping system was limited. The 1998 Berlin trials brought charges against several doctors, coaches, and officials, but because the statute of limitations for bodily-harm offenses expired in October 2000, prosecutors were forced to pursue only a handful of symbolic cases rather than a comprehensive reckoning. Many investigations were dropped; others resulted in minimal penalties.

Dr. Bernd Pansold, chief medical officer of SC Dynamo Berlin, worked closely with elite gymnasts during his tenure at the club. According to Der Spiegel, he was the doctor who prescribed the Kaiser-Schema for the gymnast Heike M., though the charges that reached court concerned underage female swimmers rather than gymnasts. In December 1998, Pansold was convicted by the Berlin Regional Court (Landgericht Berlin) of aiding and abetting intentional bodily harm in nine cases and was fined 14,400 Deutsche Marks. He appealed, but the Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof) rejected the appeal in February 2000 as unfounded.

When the East German doping system was formalized under State Plan Topic 14.25, it was Dr. Manfred Höppner who served as its chief architect. As deputy director of the Sports Medical Service, he drafted the confidential memorandum that outlined how “supporting means” would be medically administered and monitored. Manfred Ewald, then the Minister of Sport, was among those who signed off on the plan, giving it the political authority and institutional backing it needed to become policy. Together, their roles ensured that the program moved seamlessly from concept to state-sanctioned practice. In 2000, they stood trial for orchestrating the state doping program. Although initially charged in 142 cases, both men were ultimately prosecuted in only twenty as the statute of limitations approached. They were convicted of aiding and abetting bodily harm: Ewald received a suspended sentence of one year and ten months, Höppner a suspended sentence of one year and six months. Ewald’s appeal was later dismissed as unfounded.

(For readers, their names may already be familiar from gymnastics: Ewald was the official who terminated Ralf-Peter Hemmann’s career after his positive steroid test, and Höppner not only worked closely with Dörte Thümmler’s stepfather in the Working Group on Supporting Means but also traveled to Moscow to verify Hemmann’s steroid-positive B sample after the 1981 World Championships.)

The Berlin trials, limited in both scope and consequence, offered only a partial reckoning. They exposed fragments of a vast state-run experiment in human performance but stopped short of confronting the system that had made such practices routine. The sentences—when they came at all—stood in stark contrast to the lifelong harm endured by many athletes. As legal scholar Michaela Galandi noted, the proceedings were “only a partial element in the broader process of coming to terms with the past,” yet an indispensable one. Imperfect as they were, the trials nonetheless forced the crimes of the GDR’s sports apparatus into the open, ensuring that what had been hidden behind institutional silence could no longer be denied.

But the memory of this history cannot be found in court transcripts alone. It also lives in testimony—in the living, spoken, and written accounts of those who were shaped by the system and still bear its marks. This testimonial memory lives in Heike M., in Dagmar Kersten, in Dörte Thümmler, in Gabriele Fähnrich, and in those who have not yet shared their stories. Their recollections form a parallel archive: dispersed, fragile, and unignorable, expanding each time another survivor steps forward.

Together, the testimonies, the Stasi files, and the legal record trace the contours of a system that once thrived on secrecy. Breaking that silence, however, was a long and painful process. By 2018, Dörte Thümmler had found community with other former gymnasts whose stories echoed her own. They exchanged messages, shared experiences, and supported one another. That April, she spoke publicly for the first time at a press conference held by the Doping Victims Assistance Association. It was not easy, but for the first time in thirty years, she felt strong enough to speak.

From her years in elite gymnastics, one lesson had stayed with her more than any other: perseverance—the ability to keep going when everything else breaks down. The system that built her body and then destroyed it had also taught her endurance, and she now used it in another fight: for recognition, for support, for truth. “To keep going until you reach your goal, not to give up no matter how hard the years are—that’s something that does come from sport,” she said. “You learn to hold on, to fight.”

That same resolve runs through all the women who have spoken up. Their stories continue what the trials could only begin: not a legal reckoning, but a human one, carried forward not by courts but by those who lived the consequences in their own bodies.

And in that ongoing act of telling, the silence the system relied upon is finally, irrevocably broken.

References

Galandi, Michaela. Die strafrechtliche Aufarbeitung

von DDR-Zwangsdoping. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2022.

Kuban, Caroline. “Wenn ein Staat das Leben seiner Sportler auf Spiel setzt.” Deutschlandfunk Kultur, 25 Nov. 2018.

Ludwig, Udo, and Thomas Purschke. “Frankensteins Labor.” Der Spiegel, no. 35, 21 Aug. 2015.

Schmidt, Sandra. “Sie konnte sich nicht wehren.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 28 July 2018, p. 36.

Richter, Wolfgang. “Lila Trikot — aber nicht etwa der letzte Versuch,”Neues Deutschland, 26 Nov. 1987.

Zajda, Beatrice. “Für Medaillen die Gesundheit ruiniert.” Deutschlandfunk Kultur, 6 Oct. 2019.

Notes

1. Dynvital was common in the East German pharmaceutical arsenal. This is how an anonymous former rhythmic gymnast of the Children- and Youth Sports School (KJS) Halle described it: “I was nine years old when I was admitted to the sports school in 1987. From the very beginning, I was given the preparation Dynvital and blue and white tablets. I couldn’t make sense of many of the pains I had back then. Since I wasn’t a boarding student but went home alone every evening, I kept most of it to myself. I didn’t want to be a burden to anyone and withdrew more and more—even from my family. Through our coaches, many girls were subjected to emotional and physical violence. That included shouting and kicking during splits training. There were muscle strains. During weigh-ins, we had to line up wearing only our underwear, which I found very unpleasant. I experienced training tools that were reminiscent of torture, such as a spring-power exercise board. I always weighed too much back then. When I was expelled from the sport, I found it difficult to find my way in the ‘normal’ world. I was constantly afraid of doing something wrong. For me, only performance mattered. Shortly afterward, I joined the sports group SSC Einheit Halle-Neustadt. Since I only knew training through pain, I began there to deliberately inflict pain on myself during practice. Only then did I feel that I had trained well. I quit at 18. A sports physician diagnosed me with arthrosis—at a stage one would expect in an eighty-year-old.”—From: Ines Geipel, “Stellare Körper,” Trauma und Gewalt, May 2018.

2. In the early 1980s, Sotropin H—an East German preparation of human growth hormone (hGH) extracted from human pituitary glands—was widely used in both medical treatment and scientific research across the Eastern Bloc. A 1981 Bulgarian study by Peneva and Slavova in Nature followed 17 children with growth hormone deficiency who received long-term therapy with various hGH preparations, including Sotropin H. The researchers reported rapid “catch-up” growth during the first year of treatment (up to 10 cm annually), followed by slower but steady progress over several years. The study reflected the prevailing medical view that continual hormone injections could normalize height in children with pituitary dwarfism, particularly when started early and supported by thyroid therapy.

At the same time, researchers in Romania were experimenting with new methods to extract and purify human growth hormone from cadaver pituitary glands for clinical use. The 1982 paper by Simionescu and colleagues described a large-scale process for producing “clinical-grade” hGH—comparable to Western products like Crescormon (Sweden) and Raben Somatotropin (U.S.)—but noted that Sotropin H differed chemically from these international standards. Their laboratory developed a soluble, injectable form called Hormcresc and also managed to isolate several other pituitary hormones from the same tissue source.

Together, these studies show that Sotropin H was both a benchmark and a point of comparison in early 1980s endocrinological research: a state-manufactured hormone used to treat children, but also a reference compound in the race to develop safer, purer, and more standardized growth hormone preparations before recombinant DNA technology made synthetic hGH possible.