Daniela Silivaș’s age falsification is the case every gymnastics fan can name, but few know that it took more than a decade for her real age to appear. It’s a story built on a false confirmation, an overlooked sidebar, and the quiet mystery of why no one bothered to look sooner.

In 1990, after years of rumors about age falsification, the world thought it had finally learned Daniela Silivaș’s real birth year: 1971. But that certainty turned out to be misplaced. The question of her actual age would remain unsettled for another twelve years. Only in 2002, when ProSport began collecting documents and retracing old accounts, did Romanian reporters finally dial Silivaș’s number to ask.

By then, the pattern had already revealed itself twice over. First came Gina Gogean, whose birth certificate told a story that contradicted a decade of official records—a contradiction she declined to acknowledge. Then Alexandra Marinescu, who did what Gogean would not: she confirmed that her passport had been altered and pointed to her damaged body as proof of what that alteration had cost.

And then came Silivaș. ProSport’s headline put it bluntly: “The Nightmare Continues: Silivaș’s Age Was Falsified, Too!”

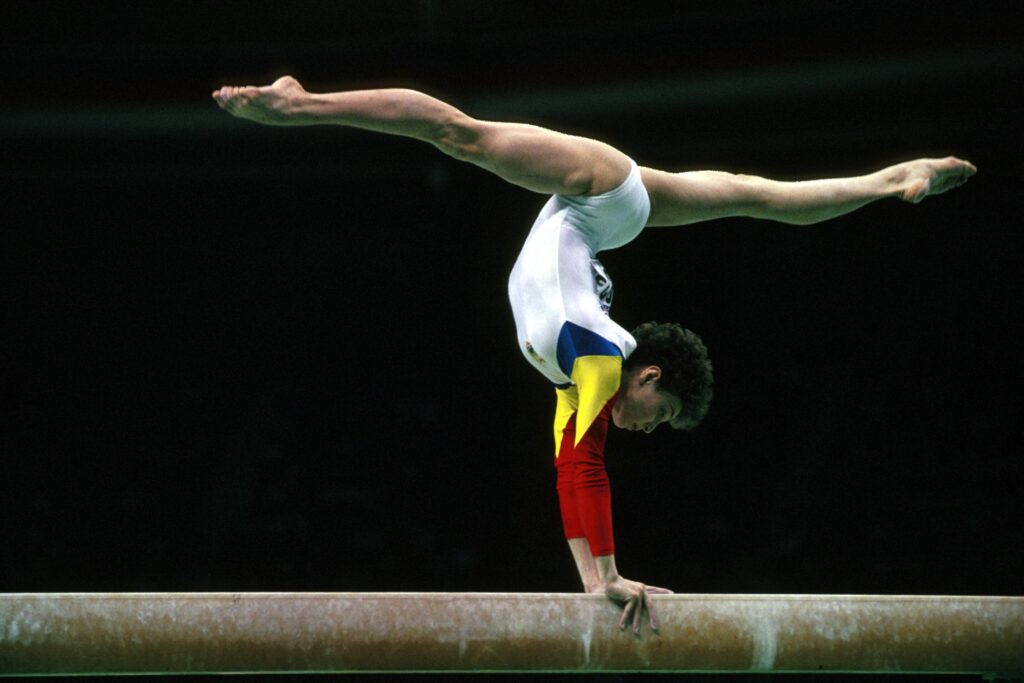

Three gymnasts. Three falsified ages. And for Silivaș—the most decorated of them all, with six Olympic medals from a single Games—the truth was finally being spoken in her own voice.

Here is the story that took more than a decade to come into focus.

A Truth Spoken in Her Name (1990)

In December 1989, Romania’s Communist regime collapsed in what is widely considered the bloodiest of the 1989 Eastern European uprisings. Protests that began in Timișoara on December 16 spread to Bucharest within days. On December 22, as the army switched sides, Nicolae Ceaușescu fled the capital by helicopter—an image that seemed to signal the end of an era. He and his wife, Elena, were captured, rushed through a drumhead trial, and executed on December 25. The National Salvation Front, led largely by former Communist Party members, seized power and promised free elections.

But the bloodshed did not end with Ceaușescu’s death. According to widely accepted figures, of the roughly 1,104 fatalities during the 1989 upheaval, about 942 occurred after December 22, when the regime had officially fallen. In the chaotic days that followed, many deaths resulted from firefights, false alarms, and alleged “terrorist” scares — though no organized loyalist network was ever definitively proven. The confusion bled into early 1990, a period when the new authorities were still improvising the architecture of a state, the economy was buckling, and competing narratives about what had actually happened in those December days began to harden into history.

Against that backdrop, in the spring of 1990, the German magazine Olympisches Turnen Aktuell (Olympic Gymnastics Update) sent reporter Thomas Schreyer to Deva, where he found the old training center operating in a strange twilight — the dictatorship gone, the structures still standing. He spoke with three familiar figures from the program’s golden decade: the recently retired Daniela Silivaș; her friend and former teammate Ecaterina Szabó, now a part-time university student and children’s coach; and Leo Cosma, who had worked with both of them during their competitive years.

Szabó, at only twenty-two, was already living in a different mode from the one enforced during her career. When Schreyer asked about age manipulation, she responded with an openness that would have been unthinkable only months earlier. She explained that she had been born in 1968, not 1967, and that many gymnasts’ passports “were simply falsified so the children could be sent earlier to international competitions.” This was not presented as rumor or speculation. It was, to her mind, a matter of record.

“It was no different for Lavinia Agache,” she continued, before adding, with the disarming flatness of a truth too familiar to sound explosive, that “for Daniela Silivaș, too, the official documents were manipulated.” She emphasized that the gymnasts themselves bore no responsibility, and that even now, “we have no idea who was responsible for the falsification of the documents.”

Between Szabó’s comments, Schreyer inserted a line that took on a life of its own: “Daniela Silivaș, who is extremely close friends with Kati Szabó, is one year younger than previously stated and will not turn 19 until this May.” In truth, Silivaș was about to turn 18, not 19, but no one fact-checked that detail. That sentence, wrong age and all, quickly grew into full-length articles.

The LA Times wrote, “Daniela Silivas, winner of three gold medals at the 1988 Seoul Olympics, told Olympic Gymnastics magazine that she was only 14 when she won her first medal at the 1985 European Championships. Silivaș said she was born May 9, 1971, and not in 1970, as listed in her competition documents.”

Nemzeti Sport (National Sport), a Hungarian sports newspaper, framed the story as the breaking of a long-standing taboo in international gymnastics. Citing the Associated Press summary of the German article, the paper emphasized that age manipulation had been an “open secret” in the sport and that those involved had remained silent because “the falsifications were not tied to just one country.” What mattered, in their reading, was not simply that Szabó and Silivaș had spoken, but why: “the fallen regime can no longer intimidate its elite athletes.” The article’s conclusion was almost optimistic—times were changing, the old constraints had dissolved, and these admissions could mark the beginning of “a process of cleansing” across gymnastics.

Meanwhile, in Romania, the press superficially covered the story. România Liberă (Free Romania) reported in April 1990 that Silivaș “was presented as being over 15 when she won her first medal at the 1985 European Championships; in reality, she was only 14.” Renașterea Bănățeană (Banat Renaissance) followed in July, citing the German magazine and noting that “before the Revolution, the birth dates of several top Romanian gymnasts were falsified.” But the coverage was brief and matter-of-fact. No official statement from the Romanian Gymnastics Federation followed; no inquiry was launched. The revelations circulated through the press without consequence. For a nation that had buried over a thousand dead just months earlier, gymnastics records were not urgent priorities.

The incorrect age, however, stuck. Six years later, in 1996, Cotidianul (The Daily) reported that “Daniela Silivaș, who admitted in 1990 that she was born on May 9, 1971—one year later than she had previously claimed—meaning she was 14 years and 185 days old when she won the gold medal on beam on November 10, 1985.” The 1971 birth year, printed in error by Schreyer, had become the accepted correction. Several years would pass before Romanian journalists discovered that Silivaș had actually been born in 1972, making her even younger than the “revealed” age suggested.

The Echo a Year Later (1991)

Months after the Olympisches Turnen Aktuell article was published, the subject of age manipulation surfaced again in December 1990— this time through an interview that Aurelia Dobre gave to the Dutch journalist Hans van Wissen for De Volkskrant (The People’s Daily). In that piece, Dobre offered an unsparing account of life inside the Deva system: the regimented hunger of training days, the punishments for minor mistakes, the political lessons substituted for schooling, and the emotional self-containment demanded of every athlete. International Gymnast later adapted Van Wissen’s article for its English-language readership in 1991, correcting several factual errors and bringing Dobre’s remarks to a wider audience.

Folded into this account was a line that echoed Szabó’s remarks. The federation, Dobre said, had falsified the ages of multiple gymnasts, and she recalled clearly that Silivaș had been “two years too young” at the 1985 World Championships, meaning she had been born in 1972—not 1971 as Schreyer had reported.

Other gymnasts corroborated the practice. Celestina Popa indicated she had been one year too young for the 1985 World Championships and described the disorientation it caused — “sometimes people asked me how old I was, and I didn’t know whether to say my real age or the one the federation gave me” — and Camelia Voinea confirmed that the adjustments were widely understood within the program.

Dobre added an unsettling judgment about age falsification: “Concerning that matter, nothing has changed since the revolution. In fact, it’s gotten worse.”

Dobre’s warning that “nothing has changed since the revolution” proved prophetic: underage entries continued, most notably with the senior debuts of Gina Gogean and Alexandra Marinescu. Yet the interviews from 1990 and 1991 generated no investigation and left no institutional trace. The question of Silivaș’s age would not resurface for another eight years—and even then, only as an overlooked detail.

A Date Hidden in Plain Sight (1999)

In August 1999, ProSport sent a reporter to Deva, where Daniela Silivaș was visiting from Atlanta. The resulting interview covered her life as a coach in the United States, her memories of training seven to eight hours a day for ten years, and her lingering frustration with the Romanian federation. She described the isolation of her competitive years with startling clarity: even though she lived ten minutes from the school, she stayed in the dormitory and was allowed home only once a month. “I can say I barely knew anything except the road from school to home,” she said. “If someone had dropped me anywhere else in the city, I probably would’ve gotten lost. My only friends were the girls on the team.”

In Atlanta, she had found a different life. The city’s mayor named her an honorary citizen shortly after her arrival, and she coached amateur-level children whose parents “pay quite a lot just for fun.” She loved rollerblading—her “great passion”—and stayed in close touch with other gymnasts from her generation: Eugenia Golea, Lavinia Agache, Aurelia Dobre, and Ecaterina Szabó, whom she spoke with at least once a week. She spent about $300 a month on phone calls. After ten years of relentless training, she had gained weight simply by stopping, and she now made time to run and blade whenever she could.

But her relationship with the Romanian federation remained bitter. “The FRG turns its back on former gymnasts,” she said. She still lacked a coaching license, and when she attended the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, “no one from the Romanian delegation agreed to give me accreditation.” She received one from the German delegation, thanks to gymnast Marius Tobă. “They made a lot of money off our work and results,” she continued. “I think that, after my results, I deserve a coaching license—at least as moral recognition.” When asked if she would do gymnastics if she could start life over again, she answered without hesitation: “Yes. But not in Romania.”

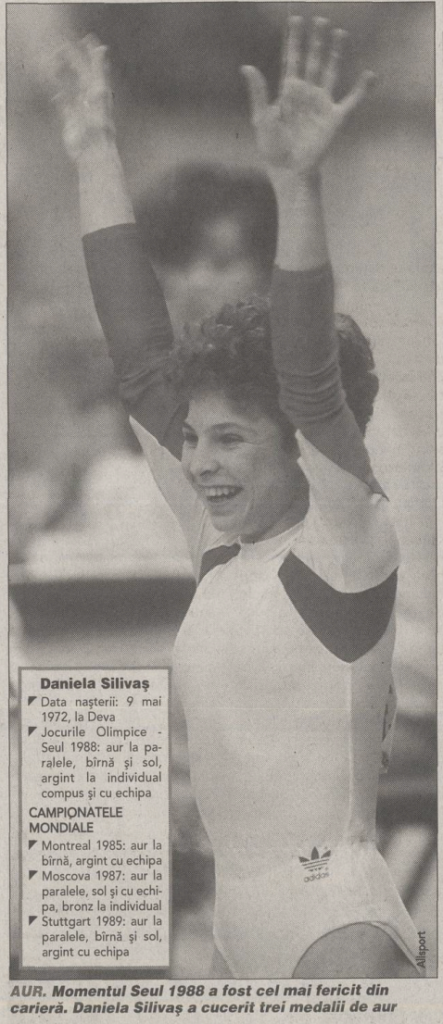

The interview filled the better part of a page. Over a photo of Silivaș, in a small sidebar listing basic biographical details, was a single line: “Data nașterii: 9 mai 1972, la Deva” (Birth date: May 9, 1972, in Deva). There it was—the correct birth year, printed clearly in Romania’s largest sports daily. But it appeared without commentary, without context, and seemingly without anyone caring.

Daniela Silivaș Corrects the Record (2002)

For three years after ProSport published that single line—”9 mai 1972″—no one followed up. No journalist asked for the story behind the date; no FIG investigation probed how or why the records had been falsified. The birth year simply sat there in the archive, a detail readers might have noticed in passing but didn’t think to question.

That changed in April 2002, when ProSport published a series of articles on age falsification in Romania. A reporter reached Silivaș by phone in Atlanta at 7:30 a.m., catching her just as she was getting out of bed.

“What year were you born in?” the journalist asked, cutting straight to the point.

Silivaș laughed, as if surprised that a reporter had to call Atlanta to confirm a Romanian birth date that should have been easy to verify at home.

“Really, nobody in Romania knows that?”

“Let’s say nobody does.”

There was a pause. Then: “I was born in ’72.”

“1972, yes?”

“Yes!”

It was the first time she had stated it explicitly, in her own voice, for an interview about age falsification. The federation passport that had declared her born in 1970—making her fifteen when she was actually thirteen at the 1985 European Championships in Helsinki—had finally been contradicted by the only person whose word truly mattered.

The journalist pressed on, confirming details. Yes, she had requested an international birth certificate from Deva city hall in 2000. Yes, all her documents in the United States showed 1972. Yes, she had competed at the 1985 World Championships in Montreal when she was only thirteen years old, despite international federation records claiming otherwise.

“Does nobody in the country actually know what happened, or…?” she asked, a note of genuine puzzlement in her voice. By this point, ProSport had already published similar cases involving Gina Gogean and Alexandra Marinescu. The pattern was emerging from the shadows.

“Did anyone ever tell you that your age would be changed?” the reporter asked. “Did they ask your permission?”

Silivaș laughed again—not with amusement, but with the rueful recognition of an absurd question. “In 1985, who was going to ask me for permission? I was 13 then. Who was going to tell me they wanted to change my age?”

She went on to provide the unvarnished reason for the falsification. After the triumph of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, most of Romania’s gold medal team had retired. “Since they didn’t have gymnasts of minimum age and medals still had to be won,” she explained, “they resorted to this procedure.” She saw the falsified passport herself eventually—the “federation passport” that stayed with Romanian officials while she traveled with her legitimate documents.

Her mother, Lucica Silivaș, confirmed the deception to the newspaper Hunedoreanul (The Hunedoara). “How could I not know when my child was born?! I can’t hide her birthdate. Daniela’s brother was born in 1970, so he’s two years older.” The coaches knew, she said, “but no one ever asked us whether we agreed or not.” Yet she offered a justification that echoed the federation’s own logic: “I think everything was done for the good of the country.”

When ProSport visited Daniela Silivaș in person later that year in Eforie Nord, where she was vacationing with family, she elaborated on the mechanics of the deception. “One of the federation officials came to me and said, ‘Here is your passport—starting today, you’re not 13 anymore, you’re 15,'” she recalled. “No one asked whether I agreed; I was just a child. They needed gold medals, and everyone involved in gymnastics knew about these practices.”

The admission carried a peculiar irony. By retiring from gymnastics in 1990, she noted, “I became two years younger.” The false age had been shed along with her competitive career, though the records in FIG’s archives would continue to reflect the fabricated birth year.

Remembering What Had Already Been Known

For twelve years, the fragments piled up: hints from former teammates, stray lines in foreign magazines, a birth year printed in a sidebar and then ignored. None of it ever carried enough weight to settle the matter.

Until April 2002.

As ProSport methodically documented age falsification across Romanian gymnastics, the question finally found the one person whose word could settle it once and for all: Daniela Silivaș herself.

What emerged from that early-morning phone call was less a revelation than a confirmation—delivered with a small laugh, as if Silivaș herself found it absurd that an international call was required to verify something any registry office in Deva could have settled in minutes. After twelve years of whispers and scattered clues, the question was finally put to rest.

But new questions emerged: What would happen next? Would the federation investigate? Would officials face accountability? Would the International Gymnastics Federation intervene?

The aftermath proved more complex than the falsification itself. The controversy moved from morning phone calls in Atlanta to television studios in Bucharest, from ministry offices to newspaper columns to FIG communiqués. It exposed how malleable sporting records could be, how limited international oversight remained, and what happened when a nation’s proudest athletic achievements collided with evidence from its own archives.

The next article in this series traces that aftermath: the shifting explanations, the defensive responses, the legal technicalities that provided escape routes, and the subtle reason why the FIG never sanctioned the Romanian federation.

References

“Cînd s-a născut Daniela Silivaș?” Románia Liberă 14 Apr. 1990.

“Coșmarul Continuă: Și Silivaș pe Fals!” ProSport 18 Apr. 2002.

“FRG ne-a întors spatele.” ProSport 20 Aug. 1999.

“Gimnastica românească în cartea recordurilor lumii.” Cotidianul 30 Nov. 1996.

“Internat in Deva aufgelöst.” Olympisches Turnen Aktuell, April 1990.

“Kamis születési dátumok.” Nemzeti Sport 13 Apr. 1990.

“Romanian Gymnasts’ Ages Faked.” LA Times 11 Apr. 1990.

“Românii au falsificat datele de naștere ale unor sportivi de performanță.” Renaşterea Bănăţeană 12 July 1990.

“Szándékos ‘öregítés.'” Népszava 13 Apr. 1990.

“Vedeta regăsită.” ProSport 26 July 2002.

Wissen, Hans van. “De verloren jeugd van Aurelia Dobre.” De Volkskrant 8 Dec. 1990.

Appendix: A Translation of the 2002 Interview

The Nightmare Continues: Silivaș’s Age Was Falsified, Too!

Daniela Silivaș burst onto the world gymnastics scene in the spring of 1985, at the European Championships in Helsinki. She had just turned 13, but the “federation passport,” as she calls the falsified document, claimed she was 15. The retirement of most members of the Romanian team that won gold at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics created a gap that had to be filled quickly. The Romanian Gymnastics Federation found a solution: age falsification. In Finland, Silivaș won a bronze medal on floor, drawing attention to herself. That autumn, Dana won on beam—the only world title captured by Romania—at the World Championships in Montreal.

Starting in 1987, when she actually turned 15, she was at the forefront of major competitions. At the European Championships in Moscow, on the territory of their fiercest rivals, she repeated Nadia’s 1975 performance in Skien: four gold medals and one silver, including the all-around title. The World Championships in Rotterdam (1987) and Stuttgart (1989), as well as the Seoul Olympics (1988), enriched her record with a pile of medals. She retired in 1990, her decision influenced in part by knee surgery she underwent earlier that year. In 1991, she moved to the United States, to Atlanta, where she currently works as the manager of Hammond Park Gymnastics and as a coach at Modern Gymnastics in Marietta (a suburb of Georgia’s capital). She has a boyfriend, Scott, a specialist in sports management, whom she plans to marry soon.

ProSport: Good morning, Daniela! ProSport newspaper from Romania here—we hope we’re not bothering you. How are you?

Silivaș: I was just getting ready to get out of bed. It’s 7:30 here in Atlanta.

ProSport: What year were you born in?

Silivaș: (Laughs.) Really, nobody in Romania knows that?

ProSport: Let’s say nobody does.

Silivaș: (Pause.) I was born in ’72.

ProSport: 1972, yes?

Silivaș: Yes!

ProSport: In 2000 you requested an international birth certificate from the city hall in Deva. Is that true?

Silivaș: Yes. I couldn’t find my old one anymore, and I needed such a document here in the States.

ProSport: So in all your documents your birth year appears as 1972.

Silivaș: (Laughs.) Yes, of course!

ProSport: You competed at the 1985 World Championships in Montreal.

Silivaș: Yes, but does nobody in the country actually know what happened, or…?

ProSport: You are listed in the international federation’s archives as being born in 1970.

Silivaș: Yes, I know that very well.

ProSport: ProSport has already published two similar cases: Gina Gogean and Alexandra Marinescu.

Silivaș: I figured they probably made them older too.

ProSport: Did anyone ever tell you that your age would be changed? Did they ask your permission?

Silivaș: (Laughs.) ’85. In 1985, who was going to ask me for permission? I was 13 then. Who was going to tell me they wanted to change my age?

ProSport: Everything happened after the Los Angeles Olympics.

Silivaș: Yes, that was exactly the problem. Many girls retired that year. Since they didn’t have gymnasts of minimum age and medals still had to be won, they resorted to this procedure.

ProSport: But after the years passed, did anyone tell you…?

Silivaș: Yes. I saw it myself later. In the federation passport I was listed as born in ’70. They kept that passport there. When I left the country, I exited with a normal passport.

ProSport: How did the coaches treat you?

Silivaș: Like in communist times. I had a hard life, but…

ProSport: Did they ever hit you?

Silivaș: Yes, and I thought the working methods would change. But Béla Károlyi’s methods remained.

ProSport: Do you remember the harshest blow you ever received from the coaches?

Silivaș: There were several, and I don’t remember those things with pleasure. But it seems there’s a big scandal in Romania right now.

ProSport: So this year you turn 30, Daniela?

Silivaș: Yes, but please don’t remind me. Time passes quickly. In three weeks I’ll turn 30. That’s life. What matters is that I work with children, and that truly makes me younger.

ProSport 18 Apr. 2002.

Note: In this issue, ProSport also confirmed that Monica Zahiu’s birthdate was actually November 3, 1983—not November 3, 1982.

Note #2: Silivaș said that her age changed in 1985, but the aging had occurred before that. In its February 29, 1984 issue, Sportul wrote, “Born on May 29, 1970, Daniela began practicing gymnastics in 1977, with her first coaches being Ioan Cărpinișan and Vasilica Grecu.”