How did people in the USSR feel about Olga Bicherova’s age falsification at the time? Did everyone simply accept that it was for the greater good of the Soviet Union?

In a 1987 essay published in Ogonyok under the provocative title “Don’t Lose the Person,” Tokarev returned to this episode not to litigate eligibility rules, but to imagine the human cost of the lie. He opened the article with the age-falsification case, identifying the gymnast only as “B” to spare her further harm. At the tournament’s final press conference, officials calmly insisted that the champion’s age complied with the rules. When a reporter produced not one but two start lists showing that she had not yet turned fourteen, officials dismissed them as “mistakes.” Only later did a federation insider admit to Tokarev that the documents had been deliberately swapped.

What haunted Tokarev was the position in which this placed the girl herself. Friends, relatives, classmates—everyone knew the truth. She was told that lying was necessary, that falsifying her age served “higher interests,” the honor and glory of the state. The burden of the deception, Tokarev suggested, fell not on officials or coaches, but on a child expected to live inside a public fiction.

(Tokarev would return to this case in 1989, writing again in Ogonyok and naming the gymnast explicitly as Olga Bicherova.)

The heart of Tokarev’s outrage, however, centers on the 1985 World Championships in Montreal. There, coach Vladimir Aksenov watched his protégé Olga Mostepanova—sitting in second place after two days of competition—be abruptly removed from the individual finals along with Irina Baraksanova. In their places, head coach Andrei Rodionenko inserted Oksana Omelianchik and Elena Shushunova, who would go on to share the gold medal. When Tokarev recounts this episode, he anticipates the response he knew so well: the medals were still Soviet medals, so what difference did it make whose names were attached to them?

Aksenov explained the reasoning to Tokarev in stark terms. Rodionenko, he said, was taking revenge. After Sovetskaya Rossiya (Soviet Russia) reported that people’s control inspectors at the Lake Krugloye training base had caught Rodionenko hoarding scarce food supplies meant for athletes, coaches were pressured to sign a letter denying the incident. Aksenov was the only one who refused. His punishment was swift: he was barred from accompanying his own athlete to Montreal, and Mostepanova was sacrificed in the finals as retribution. “Olga and Yurchenko hugged each other and burst into tears,” Aksenov recalled. “You could say that all the way back to Moscow, Olga’s eyes never dried.”

Tokarev recognizes that these individual injustices—the falsified documents, the stolen food, the vindictive substitutions—are symptoms of a deeper corruption. He challenges the notion that such deceptions serve “higher interests” or the “honor and glory of the state.” Through pointed examples, from the pentathlete Boris Onishchenko’s rigged épée at the 1976 Olympics to weightlifters caught trafficking anabolic steroids abroad, Tokarev argues that secrecy and complicity had rotted Soviet sport from within. The system demanded that witnesses sign false statements, that coaches look the other way, that everyone prioritize medals over human dignity. His closing plea is both moral and practical: sport cannot be reformed unless it embraces the same transparency and accountability reshaping Soviet society. “No medals,” he writes, “can replace for us what is most valuable—the person.”

What follows is a translation of Tokarev’s seminal essay.

Don’t Lose the Person

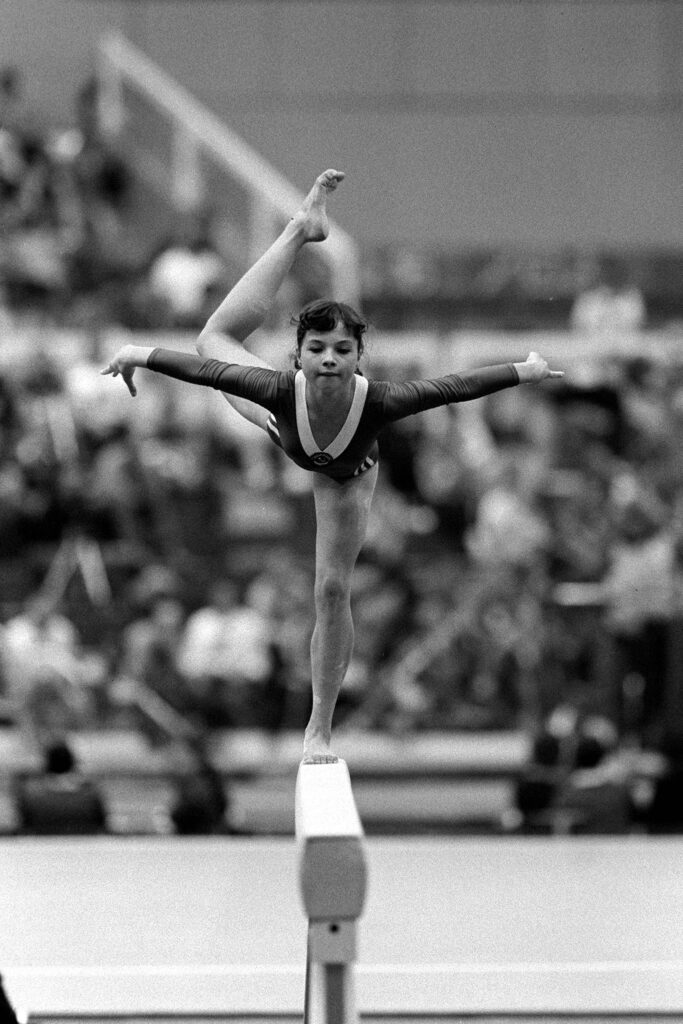

How many years ago it was now that the winner of a major international gymnastics tournament turned out to be a charming, cheerful—and of course young—athlete. So as not to offend someone who was guilty of nothing, I will designate her with the letter B.

At the tournament’s final press conference, a question was asked:

“Excuse me, how old is the champion?”

“As old as the rules require,” came the unflappable reply. “Fifteen—the age of gymnastic adulthood.”

“Then how is it,” came the follow-up, “that according to the start list of the recent national championship she had not yet turned fourteen?”

The questioner produced the protocol. The respondent’s ears flushed, but through clenched teeth he muttered:

“There’s a mistake in the start list.”

The meticulous reporter did not let it go. He produced another protocol—from an international junior competition—which showed the same thing. Again the answer:

“A mistake!”

“That’s no mistake at all—I personally saw her documents being swapped,” one of the gymnastics federation officials later said to me bitterly.

Later I asked the coach how this could have happened. The coach, an intelligent man, spread his hands and referred to an order from the senior national coach, who by then had already been dismissed.

I tried to imagine what it must have been like for the girl when everyone—friends, relatives, classmates—everyone knew everything. Of course, it stopped hurting fairly quickly, especially since she was told: this is how it has to be.

Lying, they said, is permissible—but in higher interests.

As I write this, I can almost see some high-ranking sports official indignantly explaining that at the time this was done in the name of the honor and glory of the state.

But now, when a fresh wind of change is blowing through the country, much in sport must be judged differently as well. I am convinced that no one will ever prove that falsification was “for the greater good,” and that publicity was unnecessary.

What if the famous pentathlete Onishchenko—who rigged a clever épée with a mechanism that lit up the scoreboard whenever he wanted, and was caught in disgrace at the Montreal Olympics—hadn’t been caught? Or if only his coach had known about the innovation? Would the sports authorities then have subjected Onishchenko to public ostracism?

The fact that an entire team carried bags of five-kopeck coins abroad—after someone figured out that the Soviet coin was identical to the local one used in slot machines—remained secret. In the name of the greater good. As did the fact that one “resourceful” coach added an extra zero to a foreign banknote and sent his young athlete—a minor!—to exchange it.

And what about the outstanding “iron game” masters Pisarenko and Kurlovich, whose disqualification was explained in the sports press with the traditionally evasive phrase “for behavior incompatible with…”? They too were caught abroad—in Canada—transporting a sizable dose of a preparation containing an anabolic steroid, i.e., doping, for speculative purposes.

They were punished, yes. But they should have been punished publicly, openly—so as to wash the stain from our sporting banner.

In all other areas of life this is understood today. In sport, it seems, not yet.

Here is an episode related to me by Honored Coach of the USSR Vladimir Filippovich Aksenov. He told it at a training camp near Moscow, at the sports base on Lake Krugloye [Round Lake], late in the evening silence, when everyone—exhausted—was asleep and only the floorboards creaked.

Aksenov once trained the two-time Olympic champion Elvira Saadi and the future world champion Olga Mostepanova.

So here is what happened. Sixteen-year-old Olga was competing in Montreal at a world championship. According to the rules, after two days the top three from the team would advance to the individual final.

At that moment, Natalia Yurchenko was in first place, followed by Mostepanova, then Irina Baraksanova. Behind them came Oksana Omelianchik and Elena Shushunova.

On the rest day, they went to training.

“Which apparatus do I start on tomorrow?” Mostepanova asked head coach Andrei Rodionenko.

“Work on whatever you want for now—I’ll tell you later.”

Later—at the end of training—Rodionenko gathered the girls and, averting his eyes, rattled off without explanation that neither Mostepanova nor Baraksanova would compete in the final; they would be replaced by Omelianchik and Shushunova.

Baraksanova, a newcomer, had expected something like this.

Mostepanova was devastated.

“She couldn’t pull herself together,” Aksenov recalled. “She and Yurchenko hugged each other and burst into tears. Yurchenko was the team captain; Olga was the Komsomol organizer. They cried from a sense of injustice they couldn’t explain—and no one could explain to them. You could say that all the way back to Moscow, Olga’s eyes never dried.”

“And now I’ll explain what this was about,” Aksenov continued. “Rodionenko was taking revenge on me. Sovetskaya Rossiya had written that here, at Krugloye, people’s control had caught him hoarding scarce food supplies from the athletes. Coaches were asked to sign a letter saying nothing like that had happened. I was the only one who refused. I was punished: Olga went to Montreal without me. And she was punished there as well.”

[“People’s control” (народный контроль, narodnyy kontrol) was a Soviet system of citizen oversight designed to monitor abuses, waste, and corruption in state institutions, including factories, ministries, and sports organizations. In her interviews, Mostepanova has always suggested that the substitution was done to win medals.]

People ask me, “So who won in Montreal?”

I answer, “Shushunova and Omelianchik shared first place.”

“Then what’s the problem?” they say. “If the medals stayed with us, what difference does it make whose medals they were?”

That is exactly what does not satisfy me. No medals can replace for us what is most valuable—the person.

Sport is, at its core, a game. “Who is faster,” “who is stronger.” I remember from childhood: when someone started “pressing their rights” too hard on the football field, others would shout, “What’s wrong with you? We’re not losing a cow!”—meaning that however pleasant victory may be, it must not be turned into an end in itself, a mortal necessity worth anything at all.

A member of the Central Headquarters of the All-Union “Leather Ball” Club once told me a story. At a final in Kemerovo, the local team proved far stronger than the visiting one, delighting both ordinary fans and officials alike.

But the visiting coaches were experienced people. They sniffed out that the victorious team had been assembled in violation of regulations—from multiple general schools instead of one, and even from sports schools, which was strictly forbidden. A scandal loomed.

They decided not to disband the team. Instead, they reached an agreement with the local authorities, who—would you believe it—summoned the boys and demanded that the team assembled on their own instructions lose deliberately in the semifinal. Just to be safe.

But the boys did not yet know how to lose on purpose. They won—to the horror of their own bosses—and advanced to the final.

Then, amid fist-pounding and threats of disqualification, they were ordered to give the final to the visitors.

They did. And my acquaintance went out to award them silver medals. The boys stood there crying.

“Why are you upset?” he tried to encourage them. “Silver isn’t bad either.”

“We’re crying,” they replied, “because everyone in the city knows who we really are.”

Everything told here, I believe, shows how closely sport reflects the realities of the surrounding world. In that world, breaking through the ice of zones once forbidden to criticism, the party-proclaimed process of renewal is underway.

And if someone believes that this process will not touch them personally, then I think they will never reach the finish line—no matter what endeavor they pursue.

Stanislav Tokarev, Ogonyok, 3110, 1987

Despite Everything…

The 1981 World Championships were the highlight of Olga Bicherova’s career.

“The best memory I have is the 1981 World championship in Moscow, in my hometown, when I didn’t know, until the very last minute, if I would be part of the team or not and where I at least won! I won with the team, which was something great, and then I won the all-around. I think no one could have imagined this scenario.”

More on Age