While gymnasts from North Korea and China have been penalized for age falsification, Romania never was. The logic was paradoxical: a consistent lie looked like the truth on paper.

“How should I put it… an uncaught thief is…”

Nicolae Vieru trailed off. It was early April of 2002, and the president of the Romanian Gymnastics Federation had just been confronted with a troubling contradiction: Gina Gogean’s birth certificate said 1978; her international competition records said 1977. Vieru, agitated, insisted he had never seen such a thing. When the ProSport journalist pressed—wasn’t this irregular?—Vieru laughed. “What sanctions could they take? I’m a vice president of the FIG, responsible for regulations and the statutes. There’s nothing in the rules about this.”

Weeks later, speaking on TVRM television, Vieru told a different story: “Altering ages was a worldwide practice. Just as others copied us, we copied others.”

Between those two statements, the evidence had piled up too rapidly to contain. Journalists located birth certificates in village archives. Former gymnasts confirmed that the documents submitted in their names did not match their actual birthdates. The denial collapsed within a month.

But what did that collapse mean? If passports submitted to international competitions had been accepted years earlier, did a confession in the press matter now? If the documents had been internally consistent when the FIG reviewed them, was there any mechanism to revisit what had already been approved?

The Romanian Apparatus Tries to Save Face

The answer, from Romania’s gymnastics federation, was unified defensiveness. Nicolae Vieru, who had begun the month insisting that nothing improper had ever occurred, soon sounded more aggrieved by the journalism than by the allegations themselves. “For two years,” he told Curierul Național (The National Courier), “there has been an aggressive media campaign against us. We don’t know why, nor who benefits from it.” Abroad, he insisted, Romania’s gymnasts were admired. Only at home, “where attempts are being made to dismantle gymnastics performance,” did their accomplishments seem suddenly suspect.

He returned repeatedly to the same theme: unity. With the European Championships beginning the next day, Vieru warned that the scandal was arriving at the worst possible time. “Imagine how they will be looked at,” he said of the Romanian team, “and how they will feel, when, back home, articles are being written saying their medals should be suspended, as if they were won by fraud.”

Adrian Stoica, the federation’s secretary general, took the anxiety even further. “If this continues,” he told ProSport, “we’ll have to shut down gymnastics in Romania.” It was an astonishing claim—half threat, half lament—suggesting that the real danger lay not in the falsifications but in exposing them. Stoica also insisted on the federation’s innocence: “We have never tampered with the athletes’ birth certificates.” But what about their passports, the document that the FIG relied on for competitions? In the past, he said, the Ministry had managed passport paperwork; now, gymnasts obtained the documents themselves. The implication was unmistakable: someone else’s hands had held the pen.

In drawing the distinction between birth certificates and passports, Stoica unknowingly differentiated Romania from other former Eastern Bloc systems. Soviet falsification had been more complete; according to Olga Mostepanova, even her birth certificate was rewritten. Romania’s, by comparison, relied on the passport alone.

But at this point in the scandal, Romanian officials had no interest in parsing the finer points of falsification. The story had shifted into something larger—a test of loyalty, reputation, and national pride.

From Greece, where the European Championships were underway, head coach Octavian Belu sounded personally wounded. “It’s clear that someone is against Romanian gymnastics,” he told reporters. “Too many attacks have piled up against those of us who have worked so hard for so long. It seems that someone wants us gone.” His longtime coaching partner, Mariana Bitang, echoed him with bluntness. “An attack on gymnastics,” she called it.

It was not just an attack on Romanian gymnastics. It was an attack on the entire sport.

But the denials could not hold. By the end of April, with journalists having produced birth certificates from village archives, with gymnasts themselves confirming the falsifications, with the evidence mounting beyond containment, the narrative shifted.

Nicolae Vieru, the president of the Romanian Gymnastics Federation and a vice president at the International Gymnastics Federation, appeared on TVRM television. This time, he did not offer a denial. “Altering ages was a worldwide practice,” he said. “Just as others copied us, we copied others.”

The admission was remarkable not just for what it conceded but for how casually it arrived—as if the practice, now acknowledged, had been unremarkable all along. The defense was no longer “this never happened.” It was “everyone did it.”

What the Law Said—and Why It Became the Escape Hatch

The confession might have triggered consequences. Instead, it only clarified why consequences were no longer possible.

Dan Popper, the secretary general of the Romanian Olympic Committee, explained why acknowledgment would not lead to accountability. Under Romanian law, falsifying official records was a criminal offense. But the statute of limitations was five years. By 2002, the falsifications—some dating to the 1980s—were untouchable.

“In this case, all sports structures share some degree of blame,” Popper said, “but we cannot return to a bygone era.” The acts were “already time-barred,” he continued, and therefore “there is practically no one left who can be held responsible.”

Ion Țiriac, president of the Romanian Olympic Committee, went further. Not only had the practice occurred in Romania, he said, but it had been widespread. “From the International Gymnastics Federation down to all other organizations, this was a common practice in the world of sport.” Such practices, he acknowledged, “should never have happened.” They had “predominated in former communist countries,” but also occurred “in many other countries as well.”

From his standpoint, the matter was “closed.”

The paradox was almost elegant. After weeks of insisting nothing improper had occurred, officials now conceded that it had—both Vieru, the president of the Romanian Gymnastics Federation and vice president of the FIG, and Țiriac, the president of the Romanian Olympic Committee, admitting what had been denied just days earlier. But the admission came only at a moment when the law could no longer charge anyone with a crime. No one would be named; no one would be investigated; nothing would be undone.

And with that door closed, the conversation pivoted instantly. After a meeting of the Executive Committee, Popper reassured reporters that “Romanian women’s gymnastics can recover by the Athens Olympic Games. They are capable of winning medals.” Stoica promised that despite the disturbance, “the objectives we have set for the Olympics will be achieved.”

The scandal was reduced to a matter of timing: the past had expired; the future awaited. Romania was moving on. Yet this legal closure raised a new question, one that extended beyond the nation’s borders: if the wrongdoing had occurred, and had been admitted—not by anonymous sources but by the president of the Romanian Gymnastics Federation and the president of the Romanian Olympic Committee—why had the FIG, the body charged with safeguarding the integrity of the sport, done nothing?

To answer that, one had to look at the rules the FIG itself lived by.

The Rules the FIG Had—and the Violations They Covered

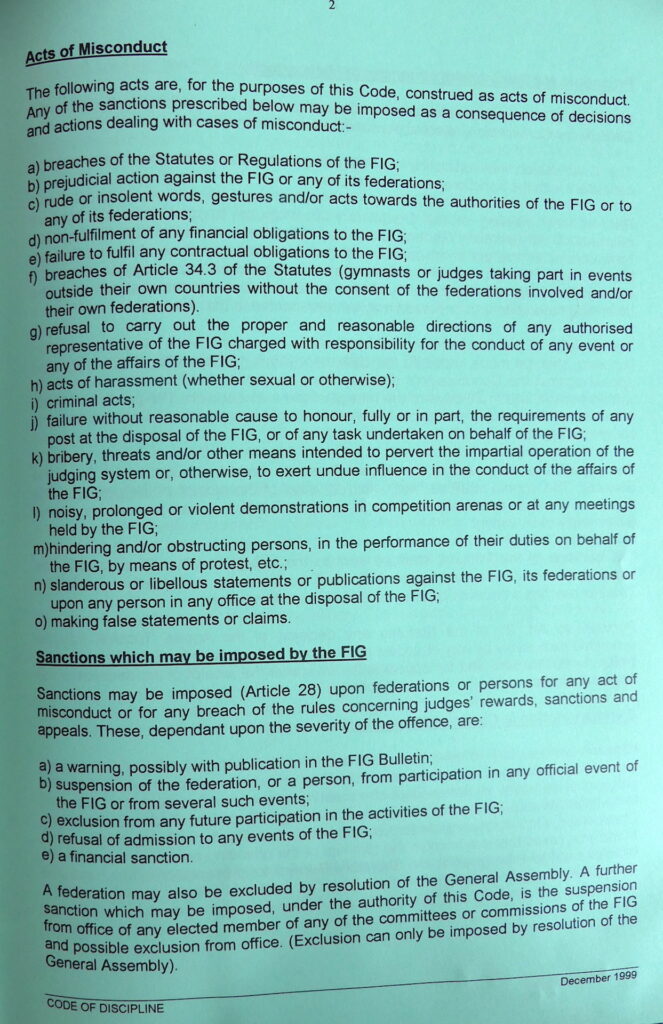

The International Gymnastics Federation, after all, was not bound by Romanian criminal law. Early in the scandal, after ProSport uncovered Gina Gogean’s birth certificate, Nicolae Vieru—a FIG vice president—insisted that there was “nothing in the rules about this.” That claim proved more hopeful than accurate. There were applicable statutes, and most importantly, the FIG’s own disciplinary regulations contained no limitation period in 2002. (Under the current Code of Discipline, such cases are time-barred, so the Romanian Gymnastics Federation could no longer be sanctioned for the falsifications from the 1980s and 1990s.)

The organization’s governing documents, updated in 1999 and still in force in 2002, granted sweeping disciplinary authority. Article 8 addressed expulsion of member federations and listed ten grounds that could warrant it: “serious breach of the Statutes or Regulations,” “serious prejudicial action against the FIG or any other member federation,” “involvement in illegal activity,” “failure to comply with anti-doping policies and measures,” among others. Expulsion required a Congressional vote, initiated either by the FIG Council or by any affiliated federation. The accused federation could present a defense in writing or through personal representation before Congress, but the ultimate authority to expel rested with the membership body.

Even without pursuing full expulsion, the FIG had another powerful tool at its disposal. Article 7 authorized suspension of member federations—a penalty that could be imposed for any of the reasons listed under Article 8. The consequences were devastating: no voting rights at the FIG Congresses, no right to make proposals or nominations for office, no participation in or right to organize any official FIG events, and no participation in activities with other member federations. In practical terms, suspension would have barred Romania’s gymnasts from the World Championships, qualifications for the Olympics, and any international competition sanctioned by the FIG. The program that had defined Romanian national identity for three decades would be effectively frozen out of the sport it had once dominated.

Both suspension and expulsion required establishing that a federation had committed acts of misconduct. The Code of Discipline, adopted as an appendix to the statutes, defined exactly what conduct qualified. It defined fifteen categories of misconduct, each actionable under the federation’s authority. For example, item (a) was for “breaches of the Statutes or Regulations of the FIG,” and item (o) was for “making false statements or claims.” The code made clear that “the FIG holds the federations responsible for the conduct of their members” and that sanctions could be imposed on federations that failed to enforce the FIG’s decisions or allowed misconduct to occur under their authority.

On paper, the Romanian case fit multiple categories. If a federation had submitted passports with false birthdates, that was a false claim under item (o). If those falsifications had allowed underage athletes to compete in violation of age-minimum rules, that was a breach of the age statutes under item (a). If the falsified documents required complicity from government officials, that meant “involvement in illegal activity” under Article 8.2(g). The framework didn’t just exist; it was comprehensive. The violations weren’t marginal cases requiring creative interpretation. They were central examples of exactly what the rules prohibited.

The question, then, was not whether the FIG had the authority to take action. The statutes made that clear. The question was how—and whether—the federation would exercise it.

The Evidence That Mattered—and the Pattern It Revealed

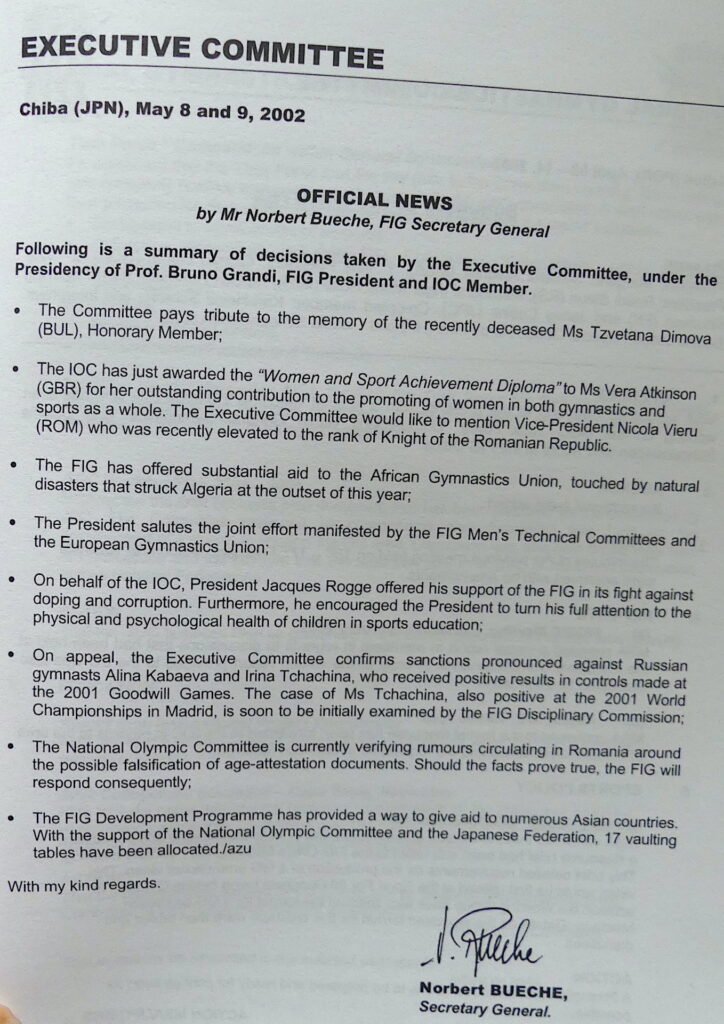

After the FIG Executive Committee convened in Chiba, Japan, in early May 2002, the organization addressed the Romanian allegations in an official bulletin. The language carried the weight of institutional resolve—measured, formal, almost prosecutorial:

Chiba (JPN), May 8–9, 2002

OFFICIAL NEWS[…]

“The National Olympic Committee is currently verifying rumours circulating in Romania around the possible falsification of age-attestation documents. Should the facts prove true, the FIG will respond consequently.”

[…]

— Norbert Bueche, Secretary General of the FIG

At the time, it sounded like a promise—or at least the outline of one. There would be a “consequential” response from the FIG if the Romanian Olympic Committee verified the rumors, but the FIG would not investigate the issue independently.

The timing of the statement was curious. Days before the Executive Committee meeting, Romania’s Olympic Committee had already acknowledged that birth years had been altered. Nicolae Vieru himself—a FIG vice president—had admitted on television that age manipulation had been “a worldwide practice” that Romania had engaged in.

By the meeting in Chiba, the “facts” had been established.

Yet the FIG did nothing.

The explanation did not appear in a ruling or a press release. It surfaced instead in a comment Bueche, the secretary general, offered to Romanian reporters early on in the scandal—one that, in retrospect, explains far more than the FIG ever officially stated. On April 16, 2002, before the meeting in Chiba, before the admissions of guilt by Romania, Ziua (The Day) printed this statement from Bueche:

“The FIG checked the passports during the gymnasts’ participation at the World Championships, and we must, of course, place trust in the state that issued these documents.”

At the time, the statement sounded like a procedural reminder of how things were done. Looking back, it defined the federation’s entire framework for determining misconduct. Gymnasts were the ages found in their passports. The FIG was not about to question the legitimacy of documents issued by a sovereign state — unless the state gave them reason to question those documents. How could they? They were not an intelligence agency scrutinizing passports for potential spies. They were a gymnastics federation.

The system functioned only insofar as the national federations and their state passport authorities acted in good faith. Some, of course, did not. In the early 1990s, North Korea entered Kim Gwang Suk into competitions with three different birth dates. At the 1989 World Championships, her birthdate was listed as October 5, 1974. At the 1991 Worlds, where she won uneven bars with a perfect 10.00, it had become February 15, 1975. By the 1992 Olympics, it was February 15, 1976. When confronted, her federation claimed the real date was February 15, 1975—one of the three versions it had already submitted.

The inconsistency was impossible to ignore. Within the FIG’s own files, North Korea had supplied birth dates that simply did not agree; no gymnast could be born three times, so they had to question the passports issued by a sovereign state. The FIG banned the PRK women’s team from the 1993 World Championships, calling the infractions “very serious” and “most unsportsmanlike behavior.” But the ban didn’t follow from suspicion that Kim was underage—everyone suspected that. It followed from documents that didn’t align with each other.

The lesson was clear: the FIG acted when its own files contained contradictory evidence. The federation was willing to compare papers, not investigate them. A consistent lie looked identical to the truth.

In Romania’s case, no matter what officials confessed on television, no matter what gymnasts said in the press, no matter what village registries showed, the FIG’s documents remained serenely aligned. The Romanians had always used the same birthdates in their FIG paperwork. Under the logic that had governed the North Korea case, there was nothing to act upon—no reason to question the passports from a sovereign nation.

In the years that followed, two high-profile cases made the logic unmistakably clear: the FIG acted only when contradictory ages appeared inside its own documentation.

The first was China’s Dong Fangxiao. The investigation began when her accreditation at the 2008 Beijing Olympics listed her birthdate as January 1986 rather than the January 20, 1983 she had competed under. Because the discrepancy arose within its own files, the FIG moved decisively. It nullified Dong’s results at the 1999 World Championships in Tianjin, her performances at the FIG World Cup Series from 1999 to 2000, and the 2000 World Cup final in Glasgow. China’s team bronze from 1999 went to Ukraine.

The FIG then took its findings to the IOC. In 2010, at the federation’s request, the IOC stripped Dong of all results from the 2000 Sydney Olympics after confirming she was only 14 during the Games—two years below the minimum age. China lost its bronze medal in the women’s team event, which went to the United States.

The second was North Korea’s Hong Su Jong. Across multiple international competitions, her birth year appeared as 1985, 1986, and 1989. Again, the inconsistency existed within the FIG’s own records. This time, the federation declined to revisit individual medals already awarded, but it imposed a broader sanction. It suspended Hong Su Jong and the North Korean federation for a period of two years, from October 6, 2010, to October 5, 2012. The PRK National Federation also had to pay a fine of 20,000 CHF.

What Accountability Never Reached

Ultimately, Romania was not sanctioned. No official investigation was opened. Romanian gymnasts did not have to shut down, as Adrian Stoica had feared. In fact, the Romanian women’s team went to the 2004 Athens Olympics and won team gold, two years after the scandal broke.

The evidence had been overwhelming. Nicolae Vieru had described age manipulation as “a worldwide practice” that Romania partook in. The Romanian Olympic Committee had confirmed that documents had been falsified. Journalists had unearthed archival birth certificates. Athletes had acknowledged that their competitive birth dates had differed from their real ones. The FIG’s own rules had been violated, and a vice president of the organization had even confessed on television.

The response was silence.

That silence revealed something fundamental about how the International Gymnastics Federation chose to enforce its own statutes. The North Korea and China cases had established the circumstances that triggered sanctions: contradictory documents inside the FIG’s own files. Romania’s case offered confession, corroboration, and external evidence—but crucially, no internal discrepancy in Lausanne’s filing cabinets. Without contradictions in its own paperwork, the federation declined to challenge official documents issued by a sovereign state, no matter how damning the outside evidence.

But was that fair? To be sure, the FIG, as a sports agency, was in no position to scrutinize the validity of a passport. But shouldn’t an athlete’s testimony be taken into consideration? Shouldn’t an organization act when its own vice president admits to violating its statutes on television?

The FIG’s approach to discipline exposed more than selective enforcement. It revealed the collapse of the entire deterrent structure on which international sports governance depends.

The federation’s statutes presumed that the threat of sanctions—suspension, expulsion, and exclusion from competition—would keep member federations in line. That threat was supposed to deter falsification, manipulation, and fraud. The logic was straightforward: if the costs of getting caught exceeded the benefits of cheating, rational actors would comply. The system depended on credible enforcement.

But if sanctions were applied only when a federation made a falsification visible in the FIG’s own files, then the deterrent failed entirely. The rules became enforceable only against incompetence, not intent. A federation could violate the age requirement with impunity, provided that it falsified documents consistently and maintained that falsification across all paperwork submitted to Lausanne. The threat of punishment disappeared for any national federations competent enough to avoid contradicting themselves.

What remained was a framework that punished sloppy fraud while offering protection to those who falsified records with precision. The lesson delivered in 2002 was paradoxical but unmistakable: lie consistently, and the system cannot touch you.

References

Alexe, Gabriela. “Nicolae Vieru: ‘Afară, toată lumea ne apreciază,în țară, se încearcă demolarea gimnasticii.’” Curierul Național 18 Apr. 2002.

Cartianu, Grigore. “Gina, Alexandra, și Daniela.” ProSport 18 Apr. 2002.

“China face losing Olympic medal after gymnast found to be under-age.” Inside the Games 26 Feb. 2010.

“Gingăras, demite-i sau demite-te!” ProSport 20 Apr. 2002.

“Îi paște pușcăria!” Monitorul 19 Apr. 2002.

“IOC EB takes decisions on Chinese gymnast Dong Fangxiao.” Olympics.com 28 Apr. 2010.

Naum, Radu. “Nu-i treziți decît pe cei care au coșmaruri.” ProSport 22 Apr. 2002.

“North Korean Gymnast Two Year Suspension!” Asian Gynnastics Union 6 Nov. 2010.

Priescu, Constantin. “Cui folosește?” Curierul Național 14 May 2002.

“Suferința copilor.” ProSport 20 Apr. 2002.

“Vîrstele s-au falsificat, dar nimeni nu e pedepsit.” ProSport 1 May 2002.

Vladu, Cristina. “Scopul nu scuză mijloacele.” Ziua 16 Apr. 2002.

Appendix: A Nation Split on Its Own Mythology

In the court of public opinion, the Romanian press did not respond with a single voice; it fractured along familiar ideological seams, revealing two different understandings of what gymnastics had meant to the nation—and what its unraveling threatened to expose.

On one side stood the columnists of ProSport and Gazeta Sporturilor (The Sports Gazette), who treated the revelations not as a shock but as confirmation. To them, the machinery of Romanian sport had always run on a logic of quiet fabrication—the athletic counterpart to the systematically falsified economic statistics that officials had once supplied to Ceaușescu. Throughout the 1980s, party bureaucrats at every level reported record grain harvests and soaring industrial outputs to meet Five-Year Plan targets, even as bread vanished from store shelves and Romanians endured rolling blackouts and food rationing. The gap between reported prosperity and lived reality had been one of the regime’s defining features, and to these journalists, falsifying birth certificates was simply another manifestation of that same gap between outward appearances and reality. Grigore Cartianu, never one to forego a dramatic flourish, wrote that, for decades, athletes had been “guinea pigs in a sick project built on the politics of lying.”

Radu Naum chose a different animal metaphor for his critique. The reaction to the scandal, he wrote, embodied “the ostrich principle—head buried as deep as possible, backside fully on display.” It wasn’t that people doubted the evidence; it was that they feared what acknowledging it might require. The “never-ending fairy tale of Romanian gymnastics,” he argued, was being attacked right at its “Once upon a time…,” and the thought of revising the story terrified a public that had been raised on its enchantments. “We do not want harm to be done to the fairies,” Naum wrote, invoking Ileana Cosânzeana—the beautiful, ethereal princess of Romanian folklore who endures every trial unscathed. No storyteller had ever paused to inform her, he noted dryly, that a heroine’s spine could suffer spondylosis, no matter how violently she was shaken by her hero’s horse. A fairy tale was not supposed to have medical records.

Naum understood what was at stake for those who buried their heads in the sand and refused to look at what was unfolding around them. For them, gymnastics was not just a sport but a national mythology—one of the few that had survived the collapse of communism and the chaotic decade that followed. The medals, the standing ovations, the televised returns at Otopeni Airport: these had been psychic scaffolding, emotional infrastructure. A country that had weathered shortages, political convulsions, and disillusionment had steadied itself, in part, on the elegance of its young gymnasts floating above the beam. To suggest that some of these triumphs had been arranged by clerical sleight of hand felt, for many, like an assault on the last intact story.

And that was precisely the point of contention for Curierul Național (The National Courier), where Constantin Priescu mounted an unapologetic defense of the sport’s honor. The accusations, he argued, risked dragging “the most glorious branch of Romanian sport” through scandal for the sake of sensationalism. Priescu invoked a reader’s letter to make his case: “Don’t you see that you are destroying everything in Romania?” the reader had written. As if questioning a birthdate could dismantle the very structure of national identity. His argument suggested something deeper and more fragile: that Romanian gymnastics had become, over decades, a kind of secular folklore. It functioned exactly as myths do—not by being literally true, but by being spiritually necessary.

In this sense, the columnists were not really arguing about falsified paperwork. They were arguing about whether a society built its dignity on truth or on the stories it needed to believe about itself. ProSport and Gazeta Sporturilor saw the age falsifications as a continuation of the lies that had sustained Ceaușescu’s regime — another set of fabricated statistics, another performance of success built on deception. Curierul Național saw them as an attack on one of the few sources of pride that had survived the transition from communism to democracy. The scandal didn’t just expose fraudulent documents; it forced Romanians to choose between competing visions of national self-respect: acknowledge the deception and lose the enchantment, or preserve the story by refusing to look too closely at how the story had been constructed.

One reply on “How Romania Broke the Age Rules and Why the FIG Looked Away”

Another in your series of excellent articles on age falsification. The victims were the gymnasts themselves and those others they took the medals from.

Georgia Cervin, “Degrees Of Difficulty”, 2021 “The FIG did relatively little about the most brazen cheating of all: age falsification…Neither the North Korean nor the Romanian gymnasts had their medals removed when their age falsifications were retrospectively revealed. The North Korean federation received minor sanctions, excluded from the world championships for a year while the Romanian federation was never punished…Indeed, the gap in time between Fangxiao’s competitive career and her reckoning cannot fully account for the actions taken against her when these measures were not also applied to Romanian gymnasts found to have competed underage after their careers had ended….Moreover, when longtime leader of the Romanian Gymnastics Federation, Nicolae Vieru, was asked to comment on these allegations, he admitted to the cheating…Despite these admissions, however, all of these gymnasts kept their medals, none of the officials received sanctions, and the Romanian Gymnastics Federation remained active in the international gymnastics community. Perhaps the FIG did not have the evidence to revoke their titles, yet there is no indication that it undertook the same kind of strenuous investigation it did for Fangxiao. Moreover, unlike the Chinese case, the accounts of various Romanian gymnasts over several generations, alongside the comments made by officials, suggest that Romanian age-falsification was systematic and remained an ongoing policy”

As Amanda Turner from International Gymnast (I.G.) magazine wrote ” Several of the gymnasts who have come out of the Romanian system have said that age-faking was common and government encouraged ( by supplying falsified passports etc)…The F.I.G banned the PRK from the 1993 World Championships, for falsifying ages but Romania is too powerful a country for the F.I.G. to try to punish them, or even investigate apparently”.

TIME magazine, July 27 1992, p.59, Jill Smolowe, “ Bela Karolyi, the US trainer, who admits to faking birth dates in his native Romania to allow underage gymnasts to perform”.