The federation manipulated Alexandra Marinescu’s age on paper; the training regimen carved lasting injuries into her spine. Together, they shaped a career that ended far too soon.

The week after revealing Gina Gogean’s age falsification, ProSport published a second case. But where Gogean’s career had been “fulfilled” and “decorated with medals,” Alexandra Marinescu’s story ended in spinal surgeries and permanent pain. Between April 15 and April 17, 2002, the newspaper documented how the Romanian Gymnastics Federation falsified Marinescu’s birth date, who made the decision, and what it cost her. What follows is a synthesis of that three-day investigation.

But first, Romanian gymnastics goes to war…

Thursday, April 11, 2002

The day after revealing Gina Gogean’s falsified age, ProSport printed an interview that put the scandal in a darker context.

Professor Dr. Ioan Drăgan, former director of the National Institute of Sports Medicine, explained the physical consequences of starting gymnastics at age six, when the skeletal system is far from consolidated. The spine becomes compressed. Growth plates may close prematurely. Puberty is delayed; sometimes menstruation is absent until age seventeen or eighteen. The marks left by early childhood training show up especially in the musculoskeletal system.

“Most problems appear over time, especially in the spinal column,” Drăgan told the newspaper, “as happened with Alexandra Marinescu.”

She was already being mentioned as a casualty even though ProSport had not yet published her birth certificate or revealed that her age, too, had been falsified.

Drăgan explained what he considered Romanian gymnastics’ central innovation: “We invented a concept: training through pain. To beat everyone else, you had to do something extra. So the girls trained and competed even when they felt pain in various parts of the body.”

Though this had been common practice in gymnastics circles, Drăgan presented it as a competitive advantage that separated Romanian gymnastics from programs that merely worked their athletes hard. Sure, everyone trained young gymnasts intensely, but Romania trained them even harder, through pain.

He offered an example. Before the Moscow Olympics, Nadia Comăneci had a fracture in the fourth lumbar vertebra “big enough to fit a finger in.” She went to the gym. She trained, but she didn’t land. With injections, with radiation therapy, she carried on. Within two weeks, she was “OK.” (In her book, Letters to a Young Gymnast, Comăneci mentions a problem with sciatica around this time.)

“In a wartime campaign,” Drăgan said, “we did many things we would never have resorted to under normal conditions.”

The war metaphor was deliberate. Gymnastics wasn’t just a sport; it was combat by other means. And in war, as Drăgan made clear, certain sacrifices were considered acceptable. The bodies of young girls, their spines compressed and their growth disrupted, were among them.

Four days later, ProSport would reveal that Alexandra Marinescu—the girl Drăgan had mentioned as an example of spinal damage—had not only been pushed literally to her breaking point but had competed under a falsified age that made her even younger than the rules allowed.

Monday, April 15, 2002

On April 10, 2002, the sports daily ProSport had dropped its first bombshell: a birth certificate from Cîmpuri revealed that Gina Gogean was born in 1978, not 1977, the year the Romanian Gymnastics Federation had supplied to the FIG. Gogean had been thirteen turning fourteen—not fourteen turning fifteen—when she stood on the Olympic podium in Barcelona with a team silver medal around her neck.

Now the newspaper had a second case.

According to her birth certificate, Alexandra Marinescu was born on March 19, 1982. According to her passport—the document that determined which competitions she could enter and which medals she could win—she was born March 19, 1981. Someone had made her a year older with the stroke of a pen.

But the two gymnasts’ stories, ProSport noted, coincided only up to a point. Gina had enjoyed what the newspaper called “a fulfilled career, decorated with numerous titles and medals at all major competitions.” Alexandra had lived something else entirely. The effects of harsh training—started at far too young an age—had left painful marks. She had retired from gymnastics in 1997, at only fifteen, at a time when some of her teammates were just entering the whirlwind of major competitions.

What followed for her could be summed up in a single word: torment.

The falsification had begun when Alexandra was eleven years old, already being heralded as a great promise. In 1993, the gymnast from the Triumf club and her father were asked a question: Would they agree to change her age?

According to ProSport, the role of negotiator fell to coach Eliza Stoica, wife of the federation’s general secretary, Adrian Stoica. The girl accepted. She was unaware of what was to follow.

Around that same time, a falsified passport was made. The person seen in those days in the corridors of the Passport Office, the newspaper reported, was none other than Adrian Stoica himself.

That is how Alexandra, aged twelve in 1994—though officially listed as thirteen—came to be the all-around champion at the Junior European Championships. She won the beam title, too, and took bronze on floor.

The push intensified. The following year, she reached the senior national team and competed at the World Championships in Sabae, Japan. She became a world champion with the team and qualified for two event finals.

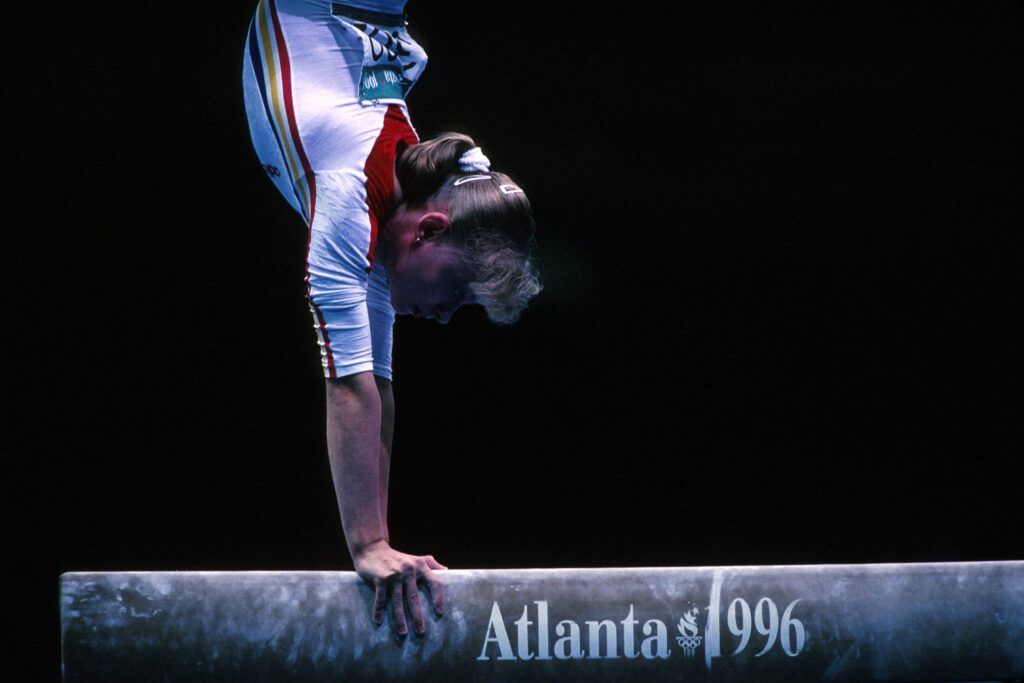

In 1996, due to bizarre age rules, she competed as both a junior and a senior. At the Junior European Championships, she defended her all-around title, and at the World Championships in San Juan, she won silver on beam. At the Atlanta Olympics that summer, she helped Romania to team bronze.

Her last major competition came in 1997 at the World Championships in Lausanne. By then, she already had spinal problems, the consequence of enormous training loads imposed too early. She added another team gold medal around her neck.

And then, she stopped.

Over three years, she underwent three spinal surgeries, the last in 2000. She came close to paralysis. Long hospital stays and terrible back pain forced her to postpone her studies. Now she was attending high school in Deva, but she never visited the gym where she had spent so many years trying to prove that she could overcome her age.

ProSport noted that Alexandra Marinescu had avoided commenting on the revelations. It appeared her silence stemmed from the fact that a book about the former athlete’s life would soon be published in the United States. There, she would make shocking and unprecedented confessions about the nine years she spent in gymnastics.

(Note: The Secrets of a Gymnast was released in the United States in 2006. It was written by ProSport reporter Andrei Nourescu.)

Tuesday, April 16, 2002

By the next day, ProSport had found her and interviewed her.

Alexandra Marinescu was living in Deva—the city that had marked her childhood, the place where she had trained under Octavian Belu and Mariana Bitang at the national center. “I like it in Deva,” she told the newspaper. “Bucharest wears me out; I don’t like it anymore.”

Yet even in the city that shaped her, she stayed away from the gymnastics hall that had defined her early life. She lived with her boyfriend, Alin Dimitriu, a DJ. Both of them knew that ProSport had published her real birth certificate and the “tampered” passport showing she had been made one year older.

When the reporter asked her age, she laughed.

“ProSport published my real age. I was born in 1982. Everything written there is absolutely true.”

She had followed everything, she said, including Gina Gogean’s case. “To be honest, I don’t know how many gymnasts this was done with. I can only speak about myself. I was taught to say I was born in 1981—one year older. With the falsified passport I have now, I was afraid to travel abroad. I was scared the authorities would catch me.”

The first time, she explained, was when she was eleven. She was training in Bucharest. “That’s where I was told I had to declare an age one year older. Then the same thing happened in Deva.”

Did her coaches know?

“Of course, they knew. How could they not know how old I was?” The question seemed almost absurd to her. “But the entire federation knew about this issue, as well. In fact, things like this happened even before I started gymnastics. I was not the first girl forced to declare an older age.”

She didn’t know anyone else in her situation personally. “But again, this is nothing new. We didn’t know much—only that we had to say we were older. Everything that was written in ProSport is completely true.”

After three spinal surgeries, Alexandra was convinced the pain would never leave her. “Because of the problems I’ve had, I’ll have pain all my life. It will never go away.” She paused, then continued: “I think about children, about their health. Why should they destroy it for sport? That’s why I don’t want to become a gymnastics coach. If I were a coach, God forbid, I might drop the girls—I would be taking a huge risk, and it’s not worth it.”

She had other plans now. Plans that had nothing to do with sport. “I want to become a DJ, to work with mixes, things like that.” She didn’t regret giving up gymnastics, she said. She was proud of what she had achieved. But that chapter was permanently closed.

“The gymnastics hall in Deva holds a sad story for me. I can say that I avoid that area every single time. There are people there who abandoned me.”

Had she spoken with Belu or Bitang?

“You already have the answer from the previous question. I have no relationship with my former coaches, and I haven’t visited them.” Her voice was steady. “Right now, the most important thing is for me to get better. God helped me get through so much suffering… For me, what was is worthless now. I’m not like other kids. What comes next is more important.”

At the federation headquarters, Nicolae Vieru saw the ProSport reporter and grabbed his coat. “Mr. Stoica is available,” the federation president said and walked out the door.

Adrian Stoica stopped working at his computer. When he spoke, his voice was firm: “I’ll repeat what I said a few days ago, after the article about Gina Gogean. The federation did not and will never handle the issuing of civil-status or identity documents, such as passports.”

He was deeply outraged, he said, that his name and his wife’s name had been dragged into this matter. “If these things can be proven, then let the law take its course. Otherwise, whoever accused us unjustly must apologize to my family.”

He had been general secretary since 1990, he explained. Before that, a federal coach responsible for men’s gymnastics. Only in recent years had the federation even received gymnasts’ birth certificates—documents required to issue a sports license. “Before ’89 and for many years afterward, licenses were issued by county commissions. Likewise, the documents needed for gymnasts’ passports were collected by the specialized department within the Sports Ministry. Now, the athletes go themselves to obtain their passports. Minors, however, are accompanied by someone from the federation.”

Across town at the Romanian Olympic Committee headquarters on Oțetari Street, the atmosphere was calmer. Almost serene.

“We have nothing to hide,” said general secretary Dan Popper. “We register Romanian athletes for the Olympic Games based on documents sent by the federations.”

He summoned Aurel Predescu, the employee who had been responsible for registering Romania’s teams for the 1992, 1996, and 2000 Olympics. Predescu’s job was simple: the COR received photocopies of athletes’ passports, then, when the definitive documents came back from organizers, he checked that the data matched. Nothing more.

“After all these revelations, what is truly regrettable is what happened to Alexandra Marinescu’s health,” Popper said. “I don’t want to seem hypocritical, but I am happy for every Olympic medal won by Romania. As for the claim that our gymnasts had their ages falsified, I had no knowledge of such things. I always asked God to give to me, never to take from me. And I never wanted to receive anything through dishonesty.”

Days earlier, Nicolae Vieru, president of the Romanian Gymnastics Federation and vice president of the FIG, had revealed a different mindset. He’d started to say, “An uncaught thief…” But he stopped himself before finishing his thought.

Wednesday, April 17, 2002

On the third day, ProSport told the story of how it happened. How twenty people in a room decided the fate of an eleven-year-old girl.

The source was a family friend, a neighbor from the Crîngași building where Alexandra’s parents lived. After the revelations, he said, the Marinescus hadn’t slept. The lights stayed on until morning.

He remembered the moment he first learned about Alexandra’s falsified age. The families were watching a gymnastics competition together on television. Commentator Cristian Țopescu was calling the action. At one point, he mentioned that Alexandra was born in 1981.

The neighbor looked at Alexandru Marinescu. No response.

“I looked at Alexandru again and said, ‘Man, your daughter is growing like in fairy tales!'”

Alexandru began to smile. And then he told the story.

In the early 1990s, the minimum age to compete as a senior was fifteen. Romania’s greatest gymnastics hope—the girl they were calling “the new Nadia”—would not be old enough for the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Not if anyone looked at her real birth certificate.

So in 1993, the machinery began to turn.

“I remember Alexandru Marinescu being extremely upset,” the neighbor recalled. He asked that his name not be used. “His daughter had worked so hard, dreaming of the Olympics. But he was troubled by something else.”

The phone calls started. Alexandra’s Bucharest coaches—Gall, Boboc, Perețeanu—calling to say that his daughter had worked for nothing. That he had to do something. The calls continued for three weeks.

Then came the question: Did he know anyone important at the Passport Office?

He was shocked, he told the neighbor. His answer was no. He knew no one.

No matter. The federation had a solution. “Until then,” the neighbor said, “they had used an old technique.”

At the time, relations between federation president Nicolae Vieru and general secretary Adrian Stoica were “icy,” according to ProSport. Neither man wanted to take full responsibility for what needed to be done. So they convened a federation meeting.

Twenty people gathered. Vieru and Stoica. Judges Maria Simionescu and Olga Didilescu. Alexandra’s coaches from Bucharest. And from Deva: Mariana Bitang and Octavian Belu.

“In the Federation Bureau meeting, they decided to falsify the documents,” the neighbor explained. “They asked for her birth certificate, and two days later they told him that Alexandra was born in 1981.”

The federation had a “connection” at the Passport Office—someone who had helped them in other similar cases. They could have solved everything quietly from the start, the neighbor said. “But they preferred to pressure the parents a bit.”

Then they called in Alexandra herself. She was eleven years old.

They told her she was no longer good enough to compete.

And then they explained: she now had a passport with a different birth date.

The falsified document still needed to look authentic. So the federation resorted to a trick.

“Alexandru told me his daughter was entered in competitions she normally shouldn’t have participated in,” the neighbor said. “They explained that they needed a few entry stamps in the falsified passport so that the document would appear authentic.”

And that’s exactly what happened.

Alexandra competed where she shouldn’t have competed. The stamps accumulated. The passport looked real.

In 1997, Alexandra Marinescu quit gymnastics. She was sick. Exhausted. Her spine—damaged by training imposed when her bones were still growing, her body still forming—could barely support her weight. Then came three nightmare years: three surgeries, each one trying to repair what the intense, early training had broken.

That same year, her father finally got the documents back. He took advantage of a day when FRG leadership was absent from headquarters, went to the secretary, and asked for Alexandra’s papers. He said he needed to take his daughter abroad for spinal surgery.

The secretary handed them over.

Alexandru Marinescu saw the falsified passport for the first time. In his hands, he held two documents: the birth certificate showing March 19, 1982, and the passport showing March 19, 1981. In the identity card issued to Alexandra at age fourteen, the birth date was the real one.

By then, it was too late. The damage was done.

The People Who Abandoned Her

When ProSport published its three-day investigation in April 2002, Alexandra Marinescu was twenty years old. Her passport still said twenty-one.

She was living in Deva, a few blocks from the gymnastics hall she never wanted to enter again. She was planning a future as a DJ, working with mixes, doing things that had nothing to do with sports. The people who had gathered in that federation meeting when she was eleven—the twenty officials who had decided to falsify her documents so she could compete for Romania—were still running the federation.

And Alexandra, who had been told at age eleven that she wasn’t good enough unless she became someone else, was certain of one thing: the pain would never go away.

“I’ll have pain all my life,” she had told ProSport. “It will never go away.”

She avoided her former coaches. She had no relationship with the people who had pushed her body beyond what it could bear.

“There are people there who abandoned me,” she said.

References

“Culisele Fabricării Unui Fals.” ProSport 17 Apr. 2002.

“Drama Alexandrei.” ProSport 15 Apr. 2002.

“Federația Nu Știe Nimic!” ProSport 16 Apr. 2002.

“Îmbătrînită Cu Forța.” ProSport 16 Apr. 2002.

“În Război Faci și Lucruri de Care Altfel Te Ferești.” ProSport 11 Apr. 2002.

Appendix A: Romanian Injuries

In 2002, doctors at the National Institute of Sports Medicine described a pattern they had seen for decades: the earlier a gymnast begins, the sooner her body breaks down. Many had retired with spinal disorders such as spondylolysis (a stress fracture in the vertebra), spondylolisthesis (a vertebra slipping out of place), or kyphosis (a forward-bending curvature of the upper spine). These were not temporary aches; they were chronic injuries that could cause lifelong pain, sometimes requiring braces, surgery, or permanent limits on physical activity.

These ailments were not exceptions. They appeared again and again in the medical histories of Romania’s most celebrated athletes—from Comăneci and Dobre to Marinescu and Miloșovici—revealing a quiet, enduring cost of a system built on extreme training loads at extremely young ages. Here’s one article on the subject.

THE SUFFERING OF THE CHILDREN

Spinal and joint diseases are the conditions that the gymnasts from the Deva national team are left with after they retire from competition.

“High-performance sport hasn’t meant health for a long time, and the younger you start, the sooner you finish,” says one of the orthopedic specialists at the National Institute of Sports Medicine. The orthopedics office is also the most frequently visited by the gymnasts on the national team. “Besides the usual sprains and fractures, the most common conditions found in these girls are those affecting the spine and the joints—illnesses from which they will never fully escape,” the doctor added.

Spondylolisthesis, spondylolysis, and kyphosis appear in almost every medical file of former and current gymnasts from the Deva team—documents stored in the archive of the National Institute of Sports Medicine.

“These are displacements of the vertebrae or deformities of the spine that cause permanent pain. The only remedies are total rest and wearing a brace.”

Supporting these observations are comments from Romania’s most decorated sports physician, Dr. Ioan Drăgan, former director of the INMS, who described the effects of excessive training loads on gymnasts. Medical studies show clearly that the body cannot tolerate, at such young ages, the physical demands required for senior-level gymnastics competition.

For this reason, the International Gymnastics Federation instituted a minimum age limit, raising it first from 14 to 15, and now to 16 years old.

THE AILMENTS OF GYMNASTS OVER THE YEARS

Suferinta copilor, ProSport, April 19, 2002

- Nadia Comăneci: spondylolysis

- Aurelia Dobre: osteochondritis dissecans

- Monica Zahiu: spondylolisthesis, spondylolysis

- Daniela Silivaș: spondylolisthesis, meniscus surgery, patella fracture

- Lavinia Miloșovici: calcaneus fracture, spondylolisthesis

- Nicoleta Onel: Scheuermann’s kyphosis

- Alexandra Marinescu: three spinal surgeries

- Alexandra Dobrescu: spondylolisthesis

- Andreea Răducan: back pain and right-ankle pain

- Sabina Cojocar: shoulder arthroscopy

- Carmen Ionescu: knee arthroscopy

- Silvia Stroescu: back pain

- Andreea Ulmeanu: ankle pain

Appendix B: The Full Text of the Marinescu Interview

AGED BY FORCE

After the three surgeries she underwent on her spine, Alexandra Marinescu is convinced she will live with pain for the rest of her life.

She is now in Deva, the city that marked her childhood, but which she chose last year as the place to settle permanently. “I like it in Deva. Bucharest wears me out; I don’t like it anymore. We’ll stay here until we decide to do something else,” the former champion says. A strange thread pulls her back there. Yet that same thread stubbornly avoids the gymnastics hall. She lives in Deva but does not visit her former coaches. Alexandra lives in the Dacia neighborhood with her boyfriend, Alin Dimitriu, who is a DJ. Both of them know that ProSport published her real birth certificate and the “tampered” passport showing she was made one year older.

The Second Falsification Case

Alexandra was born in Bucharest on March 19, 1982. When she was only 11 years old, she was asked to accept an age change, and the gymnast and her family complied. From that moment on, the girl’s new birth date became March 19, 1981, which was entered into all the official documents sent to the International Gymnastics Federation. Alexandra’s case is the second falsification reported by ProSport, which last week also published Gina Gogean’s real birth certificate, showing that her age had likewise been “increased” by one year.

She Doesn’t Want to Hear About Gymnastics Anymore

Marinescu acknowledges that everything happened exactly as reported. She paid a heavy price for the enormous efforts required of her during the period when, though still a junior, she competed as a senior. After she quit gymnastics in 1997, she underwent three spinal surgeries. “Because of the problems I’ve had, I’ll have pain all my life. It will never go away. I think about children, about their health. Why should they destroy it for sport? That’s why I don’t want to become a gymnastics coach. If I were a coach, God forbid, I might drop the girls—I would be taking a huge risk, and it’s not worth it. I have other plans for the future that aren’t connected to sport. I want to become a DJ, to work with mixes, things like that,” Alexandra says. She says she does not regret giving up gymnastics and that she is proud of what she achieved in the sport—but that’s it. That chapter is permanently closed for her.

Alexandra, how old are you?(Laughs) ProSport published my real age. I was born in 1982. Everything written there is absolutely true.

So you read the newspaper?

Yes. I followed everything, including Gina Gogean’s case. To be honest, I don’t know with how many gymnasts this was done. I can only speak about myself. I was taught to say I was born in 1981—one year older. With the falsified passport I have now, I was afraid to travel abroad. I was scared the authorities would catch me.

When did this happen?

The first time was when I was 11. I was training in Bucharest. That’s where I was told I had to declare an age one year older. Then the same thing happened in Deva.

Did your coaches know about this?

Of course they knew. How could they not know how old I was? But the entire federation knew about this issue as well. In fact, things like this happened even before I started gymnastics. I was not the first girl forced to declare an older age.

Do you know anyone else in your situation?

Not personally. But again, this is nothing new. We didn’t know much—only that we had to say we were older. Everything that was written in ProSport is completely true.

You’ve lived in Deva since last year. Have you been by the gym? How do you get along with your former coaches, Octavian Belu and Mariana Bitang?

The gymnastics hall in Deva holds a sad story for me. I can say that I avoid that area every single time. There are people there who abandoned me.

Have you spoken with Octavian Belu or Mariana Bitang?

You already have the answer from the previous question. I have no relationship with my former coaches, and I haven’t visited them. Right now, the most important thing is for me to get better. God helped me get through so much suffering… For me, what was is worthless now. I’m not like other kids. What comes next is more important.

ProSport, April 16, 2002

2 replies on “Stamped into Seniorhood: How Romanian Gymnastics Aged Alexandra Marinescu”

I thought it was Dobre with the patella fracture? I remember her ghastly looking scar in Seoul.

I knew Marinescu had troubles with her coaches (Belu and Bitang) but I didn’t know any of this. Again, thank you for your research and publishing your findings!