Judges often shy away from discussing their experiences on the record, but in the fall of 1998, International Gymnast published an interview with Darlene Darst. Over a twenty-five-year career, Darst had become one of the most respected judges in American gymnastics, officiating at national championships, world championships, and two Olympic Games. When she retired in 1992, she left a sport in which evaluation was shaped not only by performance, but also by institutional and political pressures.

Darst describes those pressures operating on more than one level. Internationally, she recounts a judging culture influenced by nationalism and informal power alignments: pre-meet score expectations, behind-the-scenes lobbying, and the understanding that judges who consistently failed to support their own countries risked fewer future assignments. During the 1970s and early 1980s, many American judges and coaches interpreted these dynamics as a structural disadvantage for the United States, particularly in competitions dominated by Eastern Bloc federations. Informal cooperation among non-dominant countries emerged as a pragmatic response within a system that was rarely perceived as neutral.

As American gymnastics strengthened, however, Darst suggests that these justifications became less persuasive. She recalls increasing pressure from U.S. coaches, particularly Béla Károlyi, to adopt the same informal practices domestically, even as American gymnasts no longer depended on favorable judging to remain competitive. Methods once framed as compensatory gradually became normalized.

The episode that crystallized this shift for Darst occurred not at an international competition, but at the 1992 U.S. Championships. She was instructed to disregard a clear out-of-bounds deduction for Kim Zmeskal, despite the fact that applying the deduction would not have affected the final standings. For Darst, the request illustrated a broader problem: accuracy was being treated as optional, even when competitive outcomes were not at stake.

In her interview with Dwight Normile, Darst offers a candid account of judging in a subjective sport, one in which professional standing could be influenced by accommodation, and where national or institutional loyalty sometimes came into tension with strict rule enforcement. Her conclusion is restrained but pointed: technical reforms alone cannot ensure fairness if judges operate within systems that reward conformity more reliably than precision.

You Be the Judge

American Darlene Darst judged at every level possible, but finally called it quits when the pressure to cheat became too great.

Does cheating occur in gymnastics judging, or do we just use it as a blanket excuse to explain controversial competition results? Darlene Darst was once one of the most venerable judges in the U.S. From 1967-92 she judged at every level: nationals, world championships, Olympic Games. She always tried to score exactly what she saw, but there were times when she was asked to do otherwise. Ridiculed if she didn’t.

It’s human nature to feel pride for your country, or at least to defend it against any wrongdoing. Internationally, judges are expected to protect the interests of the gymnasts from their own country. But when the cloud of deception infiltrated her own nation, Darst got out.

That was in 1992. Things may have changed since then. Maybe not. You would think that judging exactly what you see is the right way, the only way. But in a subjective sport, honesty is difficult to enforce and rarely praised. A blinding drive to win medals seems to supersede all, and judges are encouraged to “play the game.” Is that cheating? You be the judge.

IG: Why did you retire from elite international judging?

Darlene Darst: Well, mainly because I just couldn’t deal with all the politics and cheating anymore. So much of the cheating stemmed from the politics.

Actually, the straw that broke the camel’s back was at the 1992 USA Championships. I was judging floor. Kim Zmeskal went out of bounds along the line I was sitting on, actually in the corner, but my side of the corner. The line judge held up her flag indicating out of bounds.

At the finish of the routine, as we were figuring our scores, we were told by one of the USGF administrators that she did not go out of bounds and not to take the deduction. It was never a judgment call, for she clearly stepped over the line, as shown on TV. She was slightly out of control on a tumbling landing.

We had one more gymnast to judge. I turned my score in and said to my colleague, “I’ll never judge again at this level!”

I felt dirty and completely betrayed, and I never understood “why.” Kim won the meet without that interference.

IG: When you were receiving all your training as a judge, did they ever talk about maintaining your objectivity, or was that just implied?

DD: Oh no, they talked about it all the time. They would constantly say, “We expect the judges to give their own scores.” You know, you had to take an oath. In a way it got to the point where it was almost a joke, because you knew.

It was kind of interesting, because they would have a course the day before a big meet, a world championships or whatever. And they would have kids come in and do routines and they would judge them. And the judging was basically pretty fair. You didn’t always agree, but the judging was pretty good in terms of what was done. And then the next day it was like another scenario, another world.

IG: When you thought that other judges were giving higher scores to gymnasts from their countries, did you do the same for American gymnasts out of national pride? Should you even have pride in your country if you’re a judge?

DD: Basically, years ago, when the Eastern bloc ruled gymnastics, and we were fighting and scrounging to get recognized, our gymnasts used to do good work — not great, but good work — and they got scored terribly. The first world championships that we went to, we couldn’t get a 9.0. And our gymnasts were doing routines that were good enough to be up in the 9’s. We’d hit a routine and get an 8.6. Then Hungary would do a routine with a fall and get a 9.0.

So we were fighting at that point to try to be recognized, and of course, they controlled what was going on. They were in control of the technical committee, they were in control of the majority of the votes. And it was kind of funny, because you wondered why they had to cheat, particularly the Soviets, because they were so good, they didn’t need to do that.

But it was interesting. I did the World Cup in Madrid … and NBC was covering this meet, and they asked me on camera about the judging. And I said, “Well, basically, when judges from the Eastern-bloc countries come to the meets, if they don’t do the job that they were told to do, they don’t [judge] again. If they don’t score their kids well, they won’t judge another time.”

IG: Sounds like what we hear about women’s NCAA judging.

DD: Yeah. And at that time we never felt that way. And we — the coaches and the judges — would sit down with those other countries that were also fighting to come up — the Canadians, West Germans, Australians, British — and talk about how we could combat what was happening, the prejudice that was being shown against our gymnasts because we weren’t part of the Eastern bloc.

So we would say, “Let’s try to score our gymnasts the best you could score them.” But there was never talk about actual outright cheating. It was like you give them the benefit of the doubt if you can. If they do a good routine, try to give them as much as you can within the rules.

IG: But as a judge, why would you want to give the benefit to a gymnast of any country? Doesn’t that go against the whole concept of judging?

DD: Right. But the whole thing was to try to make sure that you gave them the best score you could, based on what they did. In other words, give them the highest that they deserved and be cognizant of the fact that maybe they were getting scored down by the Eastern-bloc judges. So it was trying to offset some of that.

Basically, I felt we were fighting like crazy to try to make them play fair, to score the gymnasts fairly.

For years I felt like that. And then, to be honest with you, the better we (the U.S. gymnasts) got, the worse we (U.S. judges) got. More pressure was put upon us as judges.

IG: Who was putting the pressure on you?

DD: (laughs) The coaches. And in my honest opinion, when Bela Karolyi came to this country the whole attitude changed.

I firmly believe that when he came to this country he definitely put pressure on the coaches of this country to do a better job of coaching. No question about that, because they wanted to try to keep up with him. But I also believe that he brought with him the Eastern-bloc mentality of “Step on whoever you need to step on to get where you want to go.” And he put pressure on Jackie (Fie), he put pressure on all of us judges. He did his very best to keep me off the floor at the USA Championships and Olympic trials in ’88 as a judge, because I judged his athletes in this country based on what they did, not on who coached them, and specifically Chelle Stack, who had zero flexibility. The compulsory routines for ’88 had five or six places where you had to show a 180-degree split in your beam routine, and she could never do a 180-degree split on the floor, much less upside-down in a handstand. And so every time that kid did a compulsory routine, I went out low on her. Well, of course, his mentality on this was that she was going to be on the (Olympic) team and she deserved to have a high score. It didn’t matter whether she was doing things right.

He constantly spoke to the press that judges — naming me and several others — scored his gymnasts down because we didn’t like him. That just was not true! And Marta (Karolyi) even made a comment to me after the fact that they knew that Chelle was not as good as she needed to be. But he went after me. But Jackie stood up for me. … In Montreal, and then in Korea, he was the one who put the greatest pressure on us because he’s the one who had all these contacts with all these foreign judges. … And he was making all these deals with all these foreign countries to score the American gymnasts. … I felt more and more pressure as a judge from the USA to make sure that certain teams got certain scores from me on the event that I was judging.

The other thing is that it began to filter down into the national program. For years there was never anything nationally. … Why would we have any kind of affinity for one particular American gymnast over another? It didn’t matter to us who won. We wanted the best gymnast on the floor.

IG: Did you ever feel guilty after a competition in which the Americans succeeded?

DD: No, I never felt guilty because I never gave a score to anybody that didn’t deserve what I gave them. And it didn’t matter if it was an American or another country. And I will say this: The response I got from other officials on the floor was that they felt my scores were always fair. And in my heart I never felt — I felt pressure, and I’ll tell you one of the experiences that happened to me in Korea (’88 Olympics). We were fighting for a position in Korea, no question about it. We would go to training, and constantly I would get comments from our coaches, “Well, we’ve talked to this country, and we’ve talked to this country … and they’re going to help us, and they’re going to help us.” And I just listened, I never did say anything. And the morning we went to the meet, the compulsory competition, we had to be there a certain time ahead. And you don’t know what event you’re judging. The FIG Women’s Technical Committee did a lot of things to try to make it fair. …And as everyone knows, I guess it’s the nature of the sport, a lot of the competition goes on before the actual day of competition in the training hall. Because how you look … in training, people see, judges see and to a certain extent you get a preconceived notion of who the best teams are and what to expect. Which I don’t think is necessarily bad.

So anyway, while I’m getting off the bus to go to this meeting … one of our coaches comes up to me and starts telling me about the Greek judge. “The Greek judge is going to do this and make sure you do this for them.” And I just got so upset I could hardly even get through the meeting. And I finally said, “Listen, I know how to do my job. You take care of your job, I’ll take care of mine.” It really did upset me so badly I was late for the meeting (voice cracking). I was in tears.

As it turned out, the Greek judge drew the same event as I did. By the way, this meet, the Olympics, was her first major international competition to judge. And as we stood in line for the march-out, she said to me, “What score do you want for your best gymnast?” And I said, “We want fair scores for all of our gymnasts. That’s all we want.”

IG: Were you ever aware of how the crowd might react to a score you were about to throw?

DD: No, but I did at times feel pressure from coaches on the floor standing behind me.

IG: Coaches from the U.S. or from other countries?

DD: Mostly other countries, but our country, too. Not so much our country because before we’d go out on the floor we’d sit down and talk about the gymnasts and what they’re doing and what kind of scores they normally get and what you can expect from them, that kind of thing. … You know them so well and you know their routines so well and you know what kind of scores they should get if they hit their routines. And so much of it is precipitated on if they hit.

For example, when we were at the (1987) world championships when (U.S. women’s head coach) Greg Marsden came out and talked about what happened, what he said was true. We got pieces of paper from the Romanians with scores on them for their gymnasts. Those were the scores they hoped their gymnasts would get if they hit their routines. … What I also found, with some of the Eastern-bloc judges, they would give those same kind of scores even on bad routines.

For example, in Fort Worth (1979 worlds), with Nelli Kim. One of the Russian judges gave her a 9.8 on a routine where she had a fall. It was absurd because you had to have at least a 9.5 because a fall is a .5 deduction (laughs). And that happened several times with some of the Eastern-bloc judges. Most of the time their scores went out [i.e., was not averaged for the final score]. But at that time, nobody was saying to them, “You cannot give a 9.8. You must bring your score down to reflect a fall on the event.” They were just letting it go. … So it kind of put you in a frame of mind to say, “Why bother?” Because they’re not going to follow the rules anyway.

That kind of thing got better. The other thing that got better was the head judges couldn’t make the other judges change their score, which happened to me at the first world championships I did. I was on the floor panel and the head judge was a Russian lady and the rules stated that you could not call an individual judge in. That if you had a conference, you had to call all of the judges in. In this particular event, she called the Japanese judge in and made her change her score on one of the Russian girls. As a result, the Russian girl’s average was the same as Joan Rice’s, who was on our team, and they tied. Joan got bumped out of the floor finals, because at that time they broke the tie with the all-around score. Well, the Russian girl had a higher all-around score. I was just crushed.

That experience, plus … Muriel (Grossfeld), coach for the American team, reamed me up and down because I went out low on two of the Canadian gymnasts. And I said to her, “Muriel, what are you talking about?”

She said, “How could you possibly score the Canadians low?” And I said, “I just scored what I saw.” I never thought about whether I was high or low on any team or gymnast. So it was kind of like, “You idiot, you should know. The Canadians are on our side. We shouldn’t go out low on them.” So that was my first experience with somebody saying you’ve got to be careful of how you score the people who are trying to help us.

IG: Was judging internationally a stressful experience?

DD: Oh, it was terrible. Very stressful.

IG: Do you think stiffer penalties would help to eliminate cheating? Right now some of the judges seem immune to the rules.

DD: The whole thing is so political. Based on my experience with judges from the Eastern-bloc countries, their idea of fair is entirely different from ours. You get what you want to get, regardless of how you can do it. Bribe, intimidate, cheat, whatever gets you the medal.

IG: When Jackie Fie became president of the Women’s Technical Committee, was the playing field fairer for the Americans? Did it help to reduce the cheating against the Americans?

DD: There were two things involved here. The medals that we won, I would never say that we didn’t deserve them, because we did deserve them. We deserved to be scored better a long time before Jackie was elected to the Technical Committee, but it didn’t happen … I know Jackie has worked very hard to make things more fair, to make the judges more accountable, and to change the system. These changes almost made judging so mechanical that we have lost the creativity of the sport. Part of that is because when you leave room for a judge to be subjective, then you leave more room for cheating.

IG: Were you ever surprised by the inexperience of some of the foreign judges?

DD: I was absolutely astounded. But when you thought about it, where were they going to get their experience? It was like that Greek judge. They had one gymnast there. I know of three judges, specifically, whose first major international meet they ever judged was the (1988) Olympic Games.

IG: Has the J.O.E. (Judges Objectivity Evaluation) computer program made a difference? At least the judges know something is out there.

DD: Yes, they know that there is something on paper. The problem with it is … part of this program ranks the judges. Unless everybody gives the same score, you’ve got to have somebody who goes out high and somebody who goes out low. And I don’t know the real specifics, but I do know the reaction of the judges is that they’re scared to death that they’re going to show up going out low all the time.

IG: Even if they’re only a tenth low?

DD: Exactly. Say the score is 9.65 and you gave 9.6. The one that gave 9.6 shows up as being low. … So what happens now is that instead of judging what they see, they are worried about how they’re going to show up on J.O.E. So that affects what scores they give. So even more, they’re trying to give scores that put them in with the average.

IG: Why do scores always seem to escalate throughout a long day of competition?

DD: In all the teaching that I have done — and I’ve trained a lot of people to judge — I have always said, “If the best kid in the meet is up first, then that has to be your highest score.” And it doesn’t matter if that kid got 9.4 or 8.6. If everybody else is worse, then everybody else’s score has to be below that. [The score] is irrelevant to what your job is, which is to rank the athletes in that particular meet on that particular day. Of course, if you have 150 kids and they’re all scoring between 9.0 and 10.0, sometimes it’s pretty hard to keep them in order. Not sometimes, it’s always hard, often impossible.

IG: Do you believe that even with all the politics, the right gymnasts usually win the medals?

DD: I kind of agree with that with a little hesitation. For example, the East Germans got third place so many times when they shouldn’t have. … There are so many things that affect the athletes and how they perform. The Chinese … were at such a disadvantage because, first of all, they didn’t speak English or French or German. They had a lot of trouble conversing with the other officials, so they were kind of like out on their own. They come into a meet and have absolutely fantastic athletes, but they don’t have any alliances. They don’t have anyone supporting them, so to speak. Their athletes, traditionally, looked absolutely fantastic in training and they fell apart in the meet. They’ve had such outstanding athletes so many times and they never seemed to be able to come into the medals. But if you look at how they performed, they made mistakes. When they make mistakes, it’s easy to score them down.

I got to know a number of the Chinese judges, and they couldn’t understand why their gymnasts didn’t get scored well. To answer your question, there were times when the Chinese should have been higher up than they were. And higher up after compulsories, which psychologically would have maybe given them a boost in terms of doing well in optionals, which is where they frequently made mistakes.

Where the teams were concerned, I think that probably numbers one and two pretty much were always the best two teams. Third place, not necessarily so. When you got into the finals, it’s a pretty hard call, because most of the time the athletes that got to finals were so good that [whoever won] depended maybe on how they competed that particular day. Or in the past, prior to “new life,” how their team did in compulsories. I know there were times when I judged finals, when I came away feeling like, “Ugh, we did a terrible job. We didn’t place them right.” But the difference between them was so fine that unless they fell or had major errors, it was almost a toss-up as to who was the best.

I remember judging (Ecaterina) Szabo in 1983 (worlds), and I was on floor in finals. And I gave her a 10.0. (Szabo’s average was a 10.0.) And her floor routine was absolutely the most magnificent thing I had ever seen. She had so much difficulty, and I mean dance difficulty …. And when I came off the floor I had a couple of our people say, “How could you give her a 10?” And I said, “Because she was absolutely magnificent.” I mean it was the best routine I had ever seen on floor up to that point in time. … And it was like, “But she’s Romanian.” And I said, “I don’t care where she’s from. She was the best.”

But there were times when I came off feeling like we just didn’t place them right. In finals all judges are from countries whose athletes are not competing in that event. Neutral, supposedly.

IG: How can things be improved?

DD: Well, if there was some way mathematically — and I firmly believe this — Don Peters (former U.S. Olympic coach) said this years ago. You put six judges on the floor, and throw out two highs and two lows and average the middle two, and mathematically there’s very little control that one judge can have. The fewer scores you count, the less influence somebody who was trying to cheat would have. And if you look at it from a mathematical point of view, he was absolutely right.

I know Jackie has tried real hard to improve upon education in the judges. But that’s only relevant to what they see. You make evaluations on what your experience is as far as your knowledge of gymnastics. What you have seen, what you see on the day you go out, your frame of reference. And as with many other things, you have a varying degree of ability out there from the judges. Some [judges] are brilliant in terms of the actual rules, but they go on the floor and they can’t see beans. And then there are others who see a lot.

They are grouping the judges now based on their test scores, which is good and bad. You have to use some method of evaluation. So if you get really high [scores] and then you judge a certain number of meets, you get into category 1, or whatever, and then they’re called the experts. So they’re trying to kind of wean people and have the [most experienced] people on the floor in the more important positions. And I think that probably has helped. And it definitely has helped that they’ve brought in women from other countries which are not necessarily gymnastics powers. Several of the Australian and English women who are excellent judges are now very highly respected. So that’s been a good thing.

[They need to] continue to provide leadership that says we will not tolerate cheating. Enforce the rules across the board, regardless of the position of the country in the rankings. Weaker countries have had to follow the rules more closely than stronger ones in the past.

Those judges caught cheating should have their license taken from them.

I believe it is impossible to take the subjectivity out of the sport, which of course leaves the door open for someone to say a judge is cheating. If you don’t agree with a score, it is easy to say “cheating.” So continue to develop methods to better evaluate and better train the judges, just as the gymnasts are better trained.

–

Dwight Normile, International Gymnast, November 1998

Appendix A: Nellie Kim’s Suspension

This is perhaps one of the most high-profile suspensions in women’s artistic gymnastics.

Busted in Brussels

Former Olympic and world champion Nelli Kim (USSR) was suspended from international judging following an incident at the World Cup, according to sources.

When scoring Svetalana Boginskaya’s vault, Kim and a Bulgarian judge put up 10.0s, despite a large hop on the landing. The other judges protested to FIG President Yuri Titov, who was forced to take action amid charges of bribery and collusion.

Kim will be required to pass the international judging exam again to be reinstated.

Similar events have occurred throughout the history of the sport. Will attacking the symptoms cure the disease? Only time will tell.

International Gymnast, February 1991

Appendix B: An Explanation of JOE

The Judges Objectivity Evaluation (JOE) system was an early computer program designed to check whether judges were ranking gymnasts in roughly the same order as the judging panel as a whole. Rather than focusing on individual scores, it looked at placements—especially at the top of the field, where medals and finals were decided. A judge who consistently ranked gymnasts very differently from the group, particularly in the fight for medals, stood out statistically. The idea was not that the panel was infallible, but that extreme outliers were unlikely to be accidental. By making those patterns visible, JOE aimed to discourage national bias, identify poor judging, and make judges more accountable for how they evaluated routines.

“Judging” Judges

A new system to monitor and improve judgingBy Dick Criley

At the 1991 World Championships, headlines from The Indianapolis Star read “Four countries’ judges to be cited for bias” and “6 countries’ judges cited for good work.”

Elsewhere, Bela Karolyi, Svetlana Boginskaya, and others were complaining about the judging, and FIG President Yuri Titov was voicing his own opinions. “Open your eyes,” he said. “The competition here is favoring the Americans. I could prove some American girls have the wrong points.”

Even FIG Women’s Technical Committee (WTC) Vice President Jackie Fie got into the act. “The first two sessions of women’s team compulsories were fine,” she said. “The judging was good. The last three rounds the scores escalated and there were a lot of unfair scores given.”

Judge-bashing has long been a popular topic among gymnasts, coaches, spectators, and others involved with sports that require subjective evaluation. Ideally, each official should apply the rules impartially and correctly. But it is possible for bias to slip in, or for a judge to look bad when consistently judging low or high. Eliminating nationalism has long been a goal of the FIG Technical Committees.

At the World Championships, a computer-based analysis was performed on each of the women judges as a test of an experimental new system: Judges Objectivity Evaluation (JOE). The actions taken by the WTC that generated the headlines were not based upon the experimental application of JOE this time, but through the personal evaluations of the WTC. In the future, however, JOE will be used.

JOE was the brainchild of Jackie Fie (U.S. representative to the WTC), who recruited Lance Crowley, a self-taught computer programmer and gymnastics coach (he runs a club in the Twin Cities, Minn.), to develop the system. Crowley and Fie began collaborating on the project in August 1990 and worked on it for more than a year. Their primary goal was to see if judges were accurately ranking gymnasts. The actual scores didn’t really matter.

IG had a chance to interview Crowley about the new system.

IG: In a competition like this (worlds), where you have 120–150 scores to rank, is this program more accurate with more scores or fewer scores?

Lance Crowley: From a statistics viewpoint, the more N’s (number of scores) the better the confidence level of the statistics, up to a point. As a very general rule, once you have more than 50 or so N’s, the stats don’t change much.We decided we would take each judge as an individual. We would compare her rank to the final rank.

IG: Which final rank?

LC: The final rank of the four middle scores out of six scores. Then we said, “Is ranking first place more important than ranking No. 200?” We decided that it was. So we weighted the ranking. For example, in places 1, 2 and 3, for every place you miss the actual rank as determined by the judges’ panel, it is multiplied by 3. Places 4, 5 and 6 are multiplied by 2.5. We call that Rate Type 1, and it is intended for Competition 1A (compulsories) and 1B (optionals) where we use every gymnast in the competition.Although we have a lot of research to do, it appears that Rate 1 measures each judge’s ability to apply the Code of Points.

The next important thing is, 36 gymnasts go to Competition II (all-around final). So let’s see how each judge ranked the top 36 kids. That’s Rate Type 2. It starts with a multiplier of 3 again. It’s a little tighter.

The next important thing is, 36 gymnasts go to Competition II (all-around final). So let’s see how each judge ranked the top 36 kids. That’s Rate Type 2. It starts with a multiplier of 3 again. It’s a little tighter.

The next most important thing is Competition III (apparatus finals). We’re only ranking eight kids because only eight make it to event finals. Rate Types 2 and 3 measure the judge’s ability to place the top 36 and the top 8 gymnasts. Rate Types 2 and 3 appear to be the best indicators of national bias.

We used the women’s average scores from the 1989 World Championships in Stuttgart as the base because we had all the scores. We input all of those as a test. The premise was that the collective jury is correct. That’s how the kids are ranked, win (or don’t win) medals. So that’s how we decided we must evaluate the judges.

We are using a statistical analysis to determine how many standard deviations you are away from the average. The reason we’re doing that is we don’t know what the base number should be. We don’t have enough experience to say, “In Rate Type 1, with 200 gymnasts, you must fall in this range.”

After this competition (1991), and I have enough time to analyze the numbers, we’ll prepare for Barcelona. We’ll establish Rate Type 1 for the judges. You must be within this range. Rate Type 2, you must be in this range, and so on.

What we saw was that some judges were totally outside 3 standard deviations, which is the 99.9 percentile. The probability of that being an accident is very, very slim. There’s one or two possibilities: Either the judge is incompetent or they are cheating. It’s hard to tell sometimes which is which.

There’s also a tendency on the part of some Eastern-bloc judges—their only concern is with the very top kids. We all laugh about the courtesy score, you know. The kid’s not going to make it anyway, so you give ’em a 9.0 and maybe the routine is only worth a 5.0. So Jackie is trying to make those judges apply the Code of Points. Judge what you see, don’t just ‘give’ a courtesy score.

…There are three separate measurements of a judge’s competence. What’s interesting to me is that one of the Eastern-bloc judges in Stuttgart was absolutely horrible. Under our present system, she’d have been red-carded (warned). She wasn’t very good in Competition IA here. She understood she was in trouble; she’s a very bright lady. She was the very best judge in Competition IB. Some of those judges know exactly what they are doing.

IG: Other comparison scores, besides the average of the middle four, that have been proposed are the scores of the two FIG control judges, who are scoring independently. If those scores are recorded anywhere, could you, as part of your testing, determine which of the mean ranks is a better one to compare against?

LC: In the program, we have slots for eight judges: two chief judges and the six panel judges. We also have the ability to do five different kinds of score averaging. We’re going to use the program as a research tool so we can go to FIG and tell them which is the most discriminating technique.…In Stuttgart, the average score for women was 9.602 (or something close to that) for almost 200 women. That means there had to be a hundred slots between 9.60 and 10.0 to separate the kids properly. Sorry, there’s only nine. These judges are boxed in to try to put 100 kids into nine slots.

The men are worse than the women because they only score in tenths, while the women are allowed to score in five-hundredths. At that, with 200 kids, that’s 200 tenths, and you’d have to score from zero to 10.0. It doesn’t make sense. I’ve suggested to Jackie that FIG consider allowing the judges to judge by one-hundredths above 9.0.

IG: It is more slots, but whether a person can really distinguish between .01 and .02, it really becomes ranking pure and simple rather than evaluation.

LC: There’s also a problem of using the head judge as one of the counting scores because the judge only has the same limited number of slots. She might say, ‘I’ve got them both at 9.9, but one of them was slightly better, but it wasn’t a 9.95.’The other positive part of this system is you can be promoted to a Brevet judge based on doing well at these competitions. We are going to use this in education and training. If we find that the judges are not correctly applying the Code of Points, then the International Judging Course will place additional emphasis on the Code.

Fie is optimistic about the new system. “JOE is a positive program to educate and improve judging. The judges are accountable to the system, to their own countries, and to themselves that they do the most efficient and fair job possible.”

If properly applied, the program can be used to improve, educate and monitor judges. In fact, with the judges knowing they were being monitored, their evaluation was much better than at the last world championships.

According to Crowley, JOE’s programmer, a review of the records from the ’91 Worlds showed that the vast majority of the women’s judges did an absolutely wonderful job. “After analyzing the results, I was very impressed with how well the judges did,” he said.

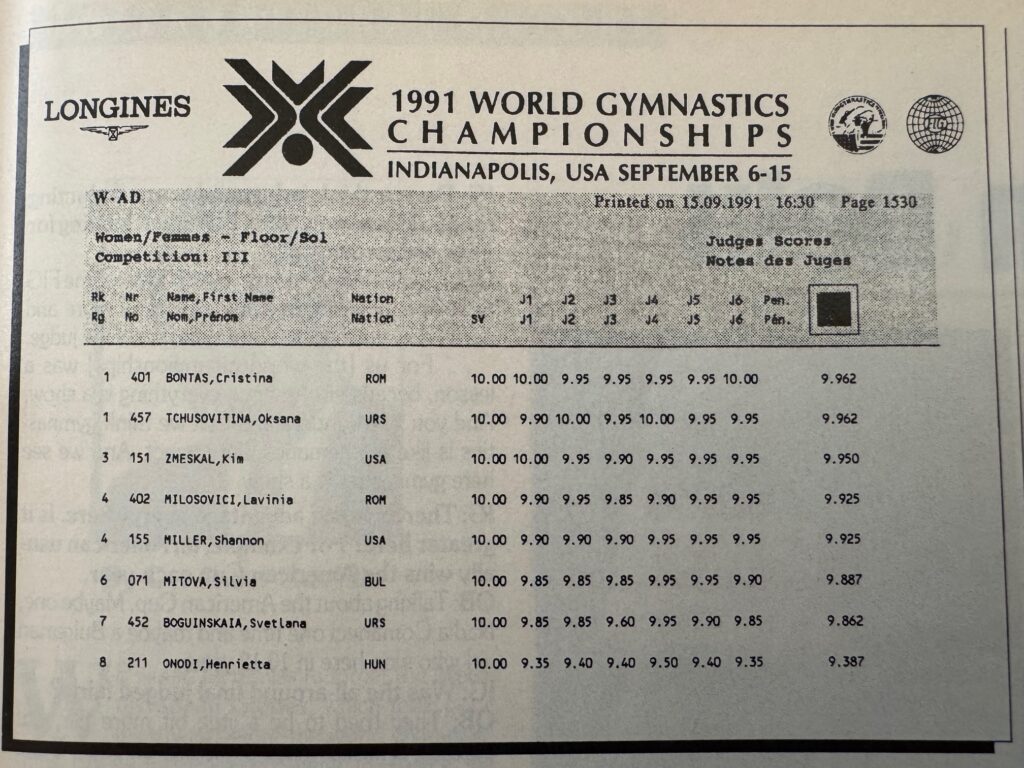

[Below] is the scoresheet from floor exercise finals at the ’91 World Championships. Note the wide range of scores for Boginskaya. Also, Judge 5 ranked six of the eight finalists at 9.95. ‘SV’ (column one) is the starting value of each routine.

International Gymnast, January 1992

More on Judging Controversies