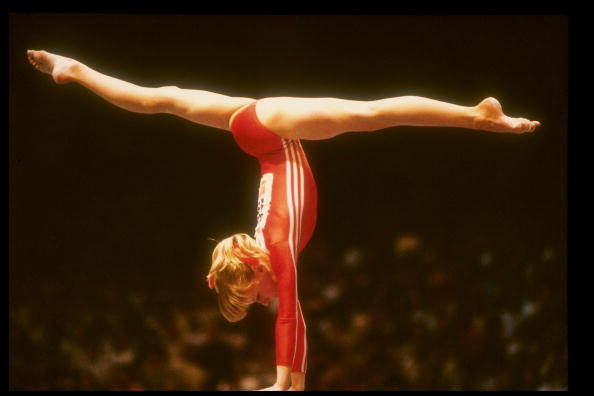

On August 27, 1984, in the Winter Stadium in Olomouc, Czechoslovakia, Olga Mostepanova achieved what no elite gymnast had ever done before or has done since: four perfect scores of 10.0 in a single all-around competition. Vault: 10.0. Uneven bars: 10.0. Balance beam: 10.0. Floor exercise: 10.0. Sovetsky Sport called it “a record—an absolute one.” Thousands of spectators rose in thunderous applause for, as a subsequent profile described her, “the fifteen-year-old winner.”

Except according to official Soviet records, Olga Mostepanova was sixteen years old in August 1984.

Or was she?

1980: “The Tiny 11-Year-Old”

The interest in Mostepanova’s age began almost from the moment she appeared on the international stage. When she competed at the Champions All tournament at Wembley Arena in April 1980, the Lincolnshire Echo marveled at “the tiny 11-year-old,” carefully specifying that she was “well in advance of her 12th birthday.” The British Amateur Gymnastics Association’s Tony Murdoch thought she “may well warrant a place in the Guinness Book of Records as the youngest ever international gymnast.”

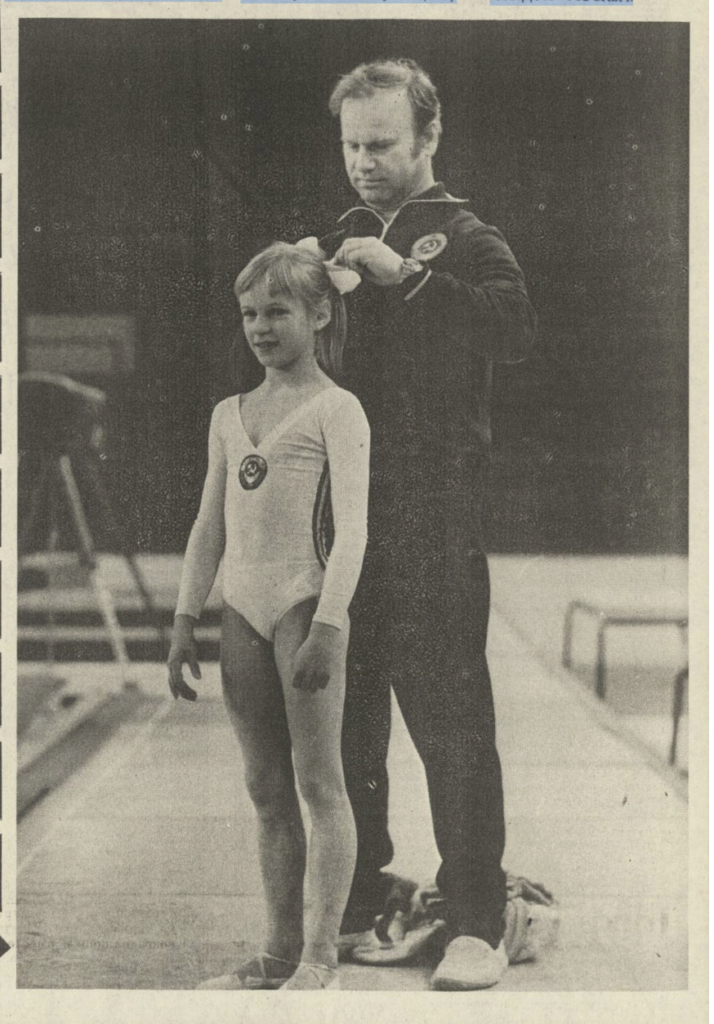

The London Daily Mirror called her “New Olya”—a successor to Olga Korbut. Photographer Arthur Sidey captured a moment that would appear in Sovetsky Sport on May 2, 1980: coach Vladimir Filippovich Aksenov tying a bow in tiny Olga’s hair before she went to compete. Editor Nikolai Semyonovich Kiselev, who had led the delegation to London, returned home emotionally enthusiastic about the 6,000-seat Wembley Arena and the crowd that roared for this fourth-grader who stood barely 1 meter 30 centimeters tall (four feet 3 inches).

She won beam with a 9.70—the highest score of the competition—along with vault and floor exercise. A mistake on bars kept her from winning outright; she placed third in the all-around. Both the British and Soviet press reported her as eleven years old, a calculation that put her January birthday in 1969, not 1968 as later official records would state.

Josef Göhler recorded that year in his “International Report” for the July 1980 issue of International Gymnastics. “Olga Mostepanova/USSR was born in 1969. Ten years old, she was the sensation of the East Bloc Tournament [Druzhba] of 1979 in Minsk/USSR, when in spite of a gross fault on the beam (9.05), she was fifth. Now eleven years old, she astounded the experts at ‘Champions All’ of London when she was among the eight girls who had been invited and occupied place three behind the two winners at a draw Rensch/GDR and Rodica Dunca/Romania. This gym infant prodigy would even have won if she had not failed in her optionals on the uneven bars (8.70). In Minsk, Olga had got for that 9.80. The winners had 37.90, and Olga had 37.55. But we would like to repeat our question: How old was she when she started serious and hard training?”

1982: The Shift

By 1982, the timeline had changed. When Mostepanova competed at the annual spring tournament in Riga in April, Sovetsky Sport reported that “victory went to the 14-year-old Moscow schoolgirl O. Mostepanova.”

Two years earlier in London, she had been eleven. Now she was fourteen. In the space of just two years, she had aged three years. Not only was she a phenom on the competition floor; she was a master of chronokinesis, as well.

The updated age held throughout the 1982 competitive season. At the Youth Games in Alma-Ata in July, the “fourteen-year-old [all-around] champion from Moscow.” At the national championships in Chelyabinsk in September, Stanislav Tokarev wrote, “Mostepanova is the discovery of the season. She is only 14, making her debut on the senior competition floor.”

In the Soviet Union at that time, 14-year-old gymnasts could compete among the seniors, even though the FIG required seniors to be 15. Thanks to an altered birth year, Mostepanova was not just competing with the seniors; she was beating many of them, placing third in the all-around at both the 1982 USSR Cup and the 1982 USSR Championships.

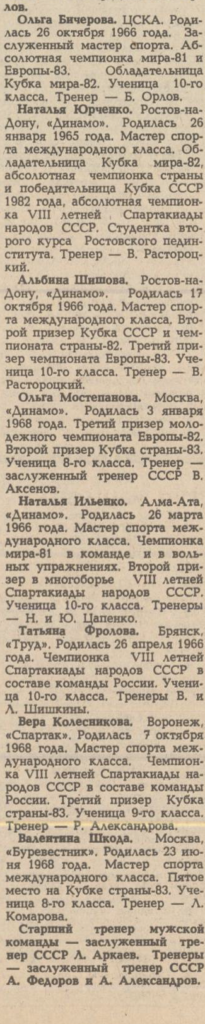

1983: Making It Official

If 1982 was the year of listing ages, 1983 was the year of printing birthdates. On May 5, 1983, Sovetsky Sport published the official roster for the European Championships in Gothenburg, Sweden. Under Mostepanova’s name appeared the falsified birthdate:

OLGA MOSTEPANOVA

Master of Sport of International Class

“Dynamo,” Moscow

Born January 3, 1968

Bronze medalist at the USSR Cup and the national championships

Bronze medalist at the European Youth Championships

Seventh-grade student

Coach: Honored Coach of the USSR V. Aksenov

There it was: January 3, 1968. The adjusted birth year that the Soviet press had used to calculate her age in 1982. She was now 15 and age-eligible for the 1983 European Championships and the 1983 World Championships, before which Sovetsky Sport published the falsification again:

Olga Mostepanova.

Moscow, Dynamo.

Born January 3, 1968.

Bronze medalist at the 1982 European Junior Championships.

Silver medalist at the 1983 National Cup.

Eighth-grade student.

Coach: Honored Coach of the USSR V. Aksenov.

At those World Championships, the Soviet team won gold, and Mostepanova won silver in the all-around behind Natalia Yurchenko, silver on floor, and gold on balance beam, becoming a world champion at what officials recorded as fifteen years old. In actuality, she was fourteen.

Though she was underage, her performance was timeless. Sports journalist Dekartova described the beam final: “In this tense atmosphere, with the high scores of Hana Řičná and Agache (both 9.85) as reference points, Olya Mostepanova completed her beam routine. She sparkled with elegance, grace, and charm—9.9 and gold.”

Senior women’s coach Andrei Rodionenko would later reflect on her success with satisfaction: “Olya Mostepanova is a world champion on balance beam, in the team competition, and a silver medalist in the all-around and floor exercise. Success? Yes. Unexpected? No, it was planned. Olya has acquired psychological stability, so her results can be predicted.”

September 1985: The Slip-up

As we saw with Natalia Ilienko, it is hard to maintain the fiction of a falsified age, and this was true in Mostepanova’s case, as well. In September 1985, Smena magazine published a feature profile by Sergey Shachin titled “A Sporting Autograph.” The article recounted Mostepanova’s greatest achievement: her performance at Friendship-84 in Olomouc, Czechoslovakia, in August 1984.

Shachin described the scene: “What the Moscow schoolgirl Olga Mostepanova accomplished at last year’s major international competition Friendship-84 can rightfully be called a record—an absolute one. In the final, she earned four perfect scores of ten points in all four events of the all-around! Thousands of spectators in the Winter Stadium in the Czechoslovak city of Olomouc greeted the fifteen-year-old winner with thunderous applause.”

According to official records for competition, Mostepanova’s birthdate was January 3, 1968, which would have made her sixteen in August 1984. But using her actual birthdate of January 3, 1969, she would indeed have been fifteen—exactly as the Smena article stated.

Later in the same article, describing her award of the Order of the Badge of Honor, Shachin again referred to “the fifteen-year-old gymnast Olga Mostepanova.” This was not a typographical error. This was the truth sneaking out.

And it was not the first time. In a November 1984 profile of Natalia Yurchenko for Smena, Shachin had calculated Mostepanova’s age using her actual birth year. Referring to the Friendship-84 Games, he wrote, “The main heroine of those major competitions, however, was 15-year-old Muscovite Olga Mostepanova, who won the all-around and three gold medals on individual apparatuses.”

15 in 1984. A 1969 birth year.

What’s interesting about Mostepanova’s age is that the slip-ups did not stop at the borders of the USSR. The Bulgarian newspaper Narodno Delo also had strayed from the official 1968 birth year. On April 23, 1983, covering the upcoming USSR-USA gymnastics meet in Los Angeles, the paper listed the Soviet women’s team roster: “Olga Mostepanova (14).”

If Mostepanova had been born on January 3, 1968, as the Soviet Union claimed, she would have been fifteen in April 1983, not fourteen. The Bulgarian press, like the journalists at Smena, had information suggesting she was actually a year younger than Soviet official sources claimed.

Montreal 1985: “We’re Human Beings Too”

“Olomouc was my shining hour—my swan song,” Mostepanova would say in a 1998 interview.

The months after perfection in Olomouc brought a cascade of setbacks. Mostepanova had barely returned when she fell ill and spent two and a half months bedridden. Then she injured the ligaments in her leg. As soon as she recovered, she injured the same leg again.

By 1985, another challenge had emerged: Elena Shushunova. Where Mostepanova was lyrical and balletic, Shushunova was explosive and sharp. “My fault,” Mostepanova reflected years later. “Vladimir Filippovich always preached beauty in gymnastics. I became too carried away with choreography and neglected physical conditioning.”

Still, she made the team for the 1985 World Championships in Montreal. After the compulsory and optional rounds, she stood third overall (78.575), behind Romania’s Ecaterina Szabó (78.750) and Natalia Yurchenko (78.650). Irina Baraksanova (78.500), Oksana Omelianchik (78.175), and Shushunova (78.025) followed close behind.

On the rest day, the team trained as usual. At the end of training, Rodionenko gathered the gymnasts and, avoiding their eyes, announced that neither Mostepanova nor Baraksanova would compete in the final. They would be replaced by Omelianchik and Shushunova.

The explanation would change over time. Officially, it was about injuries. Later, Mostepanova would say it was a strategic decision—perhaps even the correct one. But her coach, Vladimir Aksenov, told a different story. According to him, the substitution was retaliation.

Sovetskaya Rossiya had reported that inspectors at the Lake Krugloye (Round Lake) training base caught Rodionenko hoarding food meant for athletes. Coaches were pressured to sign a letter denying it. Aksenov refused. “I was punished,” he told journalist Stanislav Tokarev. “Olga went to Montreal without me. And she was punished there as well.”

Whatever the motive—strategy, injury, or politics—the result was the same. Mostepanova was shattered.

“She couldn’t pull herself together,” the journalist Stanislav Tokarev recalled. “She and Yurchenko hugged and cried. Yurchenko was the team captain; Olga was the Komsomol organizer. They cried from a sense of injustice they couldn’t even explain. All the way back to Moscow, her eyes never dried.” At the time, USGF News noted that Yurchenko was impacted by what happened: “The controversy affected Natalia Yurtchenko, who looked distant and was presumably upset by the substitution.”

Shushunova and Omelianchik went on to share the gold. Soviet officials shrugged: if the medals stayed in the USSR, what difference did it make who won them?

Years later, Mostepanova spoke carefully. “That was the decision of the coaching staff,” she said in 1998. “Even then—and now—I understand that Andrei Fyodorovich made the right call.”

But in 1989, when she spoke to journalist Natalia Kalugina, the wound was still raw:

“It’s hard to talk about it. The substitution was probably justified. After all, Szabó was ahead of us, even if only by thousandths. But couldn’t they have told us earlier? Couldn’t they have explained it, comforted us? We’re human beings too. Ira and I just cried. I cried all day, and she tried to make sense of it.”

“We’re human beings too.” The plea cuts through everything else. She wasn’t arguing for a medal. She was asking for honesty, for explanation, for dignity.

She was officially seventeen but actually sixteen. And in a system willing to falsify a child’s age for advantage, there was little room to treat that teenager as a person once her ability to win came into question.

Journalist Vladimir Golubev, who had followed her career from the beginning, agreed. “I saw it myself—she sobbed. It was terribly unfair. Pure politics. She never recovered from that blow. She left the gym.”

In a 2008 interview with International Gymnast, Mostepanova echoed that sentiment: “After this [incident], I decided to quit gymnastics and not come back,” she says. “But it was thanks to some good people in Moscow who helped me a lot to not feel bad about gymnastics and to not to feel bad about some particular people. I decided that I will leave [my decision to quit gymnastics] on the conscience of the people who were responsible.”

1998: The Confession

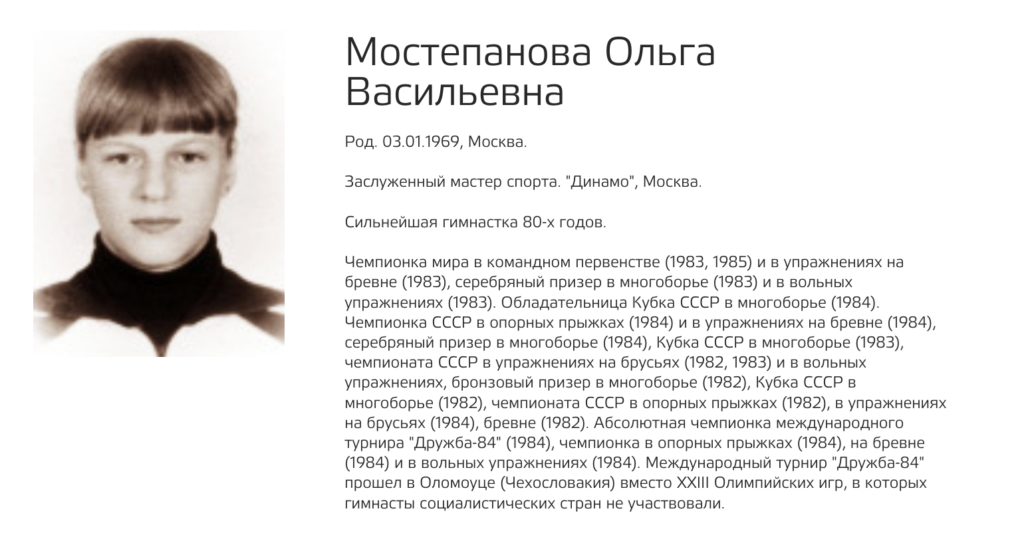

Thirteen years after her final World Championships appearance, Mostepanova herself confirmed what the documentary record had already made clear. In a Sovetsky Sport interview published on March 7, 1998, the paper opened with a corrected biographical note: “From the Sovetsky Sport files. Olga Vasilyevna Mostepanova was born in Moscow on January 3, 1969.”

The correction was explicit. The official records that had listed her birthdate as January 3, 1968, were wrong. She had been born in 1969, just as the 1980 London coverage had suggested.

Mostepanova explained to journalist Evgeny Avsenyev how it happened: “My new coach, Vladimir Filippovich Aksyonov (Anikina passed me to him), made me a new birth certificate, adding a couple of years, so I could compete as a senior.” That’s why in 1982, at age thirteen, she was already competing at the USSR Championships in Chelyabinsk and the USSR Cup in Leningrad. She finished third at both, winning silver on floor and bars, bronze on beam and vault. She made the national team. Her second place in the all-around at the 1983 USSR Cup in Rostov-on-Don opened the door to the World Championships in Budapest that year.

“I didn’t think about age then,” she said. “I trusted my coach.”

Her description of the 1983 World Championships carried a note of wonder: “I took the silver in the all-around as a gift. For a fourteen-year-old girl, not even officially old enough to compete at Worlds, that was a great stroke of luck!”

The admission was straightforward: she had been fourteen at the 1983 World Championships, not fifteen as official records claimed. She, in effect, had won gold on balance beam while being one year younger than the FIG’s age requirements stipulated.

(In a 2008 interview with International Gymnast, Mostepanova would later insist that she had never given an interview specifically about her age, suggesting that she had never discussed the matter in the way the 1998 Sovetsky Sport article presented it. She did confirm that her age had been altered.)

The interview included an editor’s note from Vladimir Golubev, the same journalist who had covered her career for years: “And yes, I know about the fake birth certificates. Not only Olga, but other young gymnasts had their ages ‘adjusted.’ The goal was victory—at any cost—to beat the Romanians and East Germans at the Olympics that never happened for us.”

Golubev’s note confirmed that the age falsification had been part of a broader pattern within Soviet gymnastics, and that those close to the program had known about it. In fact, in retrospect, we can see how Golubev obliquely pointed to the falsification in 1982, the year when Mostepanova’s age changed.

After watching Mostepanova compete at the USSR Cup in Leningrad’s Yubileyny Sports Palace, Golubev wrote a report titled “Protect Talent”:

“It is probably necessary to focus attention on another problem as well—the haste involved in ‘sending young gymnasts out into the big world.’ Let us recall how brightly Alla Mysnik’s talent flared at last year’s Cup. That talent attracted gymnastics officials in the sports societies and republics so strongly that Alla was forced to compete in every possible competition. Eleven tournaments in a single season—that is simply too much! The strain took its toll: injury, illness, surgery. And now Mysnik is no longer in first place, but in tenth.”

Then Golubev turned his attention directly to Mostepanova: “Are we not rushing things by admitting such extremely young girls as Tanya Kim, Valya Shkoda, and Olya Mostepanova to the grueling adult marathon (and a team one at that, where the responsibility is especially great)? Yes, Olya held up, but the others did not—they dropped out of the competition. Care, and care again, is what our talents need. Haste will lead to nothing good and will only cause harm.”

Read on its own, Golubev’s 1982 column appears to be a general meditation on tempo: the dangers of accelerating development, of pushing young gymnasts into the senior circuit before their bodies—and careers—were ready. His language is careful and abstract, framed around overload rather than illegality. But read alongside his 1998 admission, his emphasis on haste takes on a sharper meaning. What he was warning against was not merely the risk of too many competitions, but the logic that demanded acceleration at any cost—even falsifying birthdates to make that happen. (Mostepanova was not the only gymnast in the article whose age had been falsified.)

Today, the Russian Gymnastics Federation no longer maintains the fiction of Mostepanova’s birth year. Its Hall of Fame lists her birthdate as January 3, 1969—the date she confirmed in 1998, and the date consistent with the 1980 coverage that first introduced her to international audiences as “the tiny 11-year-old.”

Between the Dates

That tiny 11-year-old girl. It’s worth pausing on her for a moment.

Before the injuries, before the substitutions and silences, before the calculus of who could be spared and who could not, before the age falsification, there was something else entirely. There was someone else entirely. There was the gymnast everyone saw before the system closed in around her.

Vladimir Aksenov remembered discovering her at Dynamo: not especially striking in appearance, but sharp, fast, endlessly alive. “Training with Saadi took all my time; there wasn’t a minute to spare. And yet, willy-nilly, my gaze kept drifting to the far end of the hall, where the group of Anna Semyonovna Anikina, our wonderful children’s coach, was training. One girl caught my attention—awkward-looking at first glance, still a bit angular in a childish way, but sharp, mobile, full of spark. And what a beautiful leg lift she had—pure ballet! She was a mischievous, laughing girl. During warm-ups, she liked to hide on the balcony, then suddenly dash into the hall, hopping and spinning her girlfriends around… And kind-hearted Anna Semyonovna couldn’t even scold her; she would only wag a finger.”

Choreographer Elena Kapitonova tried to capture that joie de vivre in her floor routines: “I’m very afraid of overpraising Olyenka, but believe me, working with her is an enormous pleasure. I felt the same joy of creativity when working with Masha Filatova. Olga has several floor routines, but the one shown in London—“Flight of the Bumblebee”—is still the dearest to me. On the floor, Olya is obedient, attentive, and exceptionally precise. Through movement, she conveys her age and mood exactly. “Flight of the Bumblebee” is spontaneity and playfulness.”

In her work with Mostepanova, Kapitonova was reminded of Maria Filatova. Her coach, Vladimir Aksenov, aimed for something different. “Let’s try to combine in your gymnastics the complexity and risk that distinguished Korbut with the poetic beauty of Saadi,” he once said. “Can you imagine what kind of fusion that might create?”

In the end, what emerged was something even more singular than a Saadi–Korbut-Filatova hybrid. As journalist Natalia Kalugina wrote in 1989, “There was in her something of the astonishing, ringing beauty of Natalia Kuchinskaya, the spontaneity of Olga Korbut, the concentration of Ludmilla Tourischeva—and yet she remained entirely herself, unique and inimitable.”

And that is what the documents ultimately show. Not simply that her age was falsified, but why the adults around her felt compelled to do it. They saw something extraordinary and believed it should not wait. Her instinct for movement, her discipline, her ability to mix difficulty and artistry at once brought early victories and medals—public proof that seemed to confirm what they already believed. She was inimitable, and with podiums appearing before her teenage years even started, patience began to feel not just unnecessary, but impossible.

So, the Soviet sports machine found a way to avoid waiting.

Coda: The 1970 Claim

Some websites, including gymnastics reference sites, list Mostepanova’s birthdate as 1970 rather than 1969, noting that Mostepanova herself claims she was born in 1970. This is the piece of the puzzle that has stumped many people over the years. The third date likely stems from a literal interpretation of a 1998 statement that Mostepanova’s coach “made me a new birth certificate, adding a couple of years” (прибавив пару лет).

Taken mathematically, “a couple” could be read as exactly two years. Since her competition documents listed her as born in 1968, that arithmetic would place her actual birth in 1970 (1968 + 2 = 1970). But the documentary record shows that she was not born in 1970.

Contemporary sources consistently place her birth in early 1969. British and Soviet coverage from London in 1980 described her as “the tiny 11-year-old” who was “well in advance of her 12th birthday”—impossible if she had been born in 1970. Bulgarian press in April 1983 listed her as fourteen; Smena in 1985 called her fifteen in August 1984; and International Gymnast published 1969 as her birth year in 1980 and in 2008. All of these independently point to a January 1969 birth.

In this context, “a couple of years” clearly meant “a year or so,” not a precise calculation. The falsification added one year, shifting her official birthdate from 1969 to 1968.

References

Primary Sources – Contemporary Newspaper and Magazine Coverage:

“Russian team include 11-year-old.” Lincolnshire Echo, April 3, 1980.

Kiselev, N. “‘New-Olya’ with a Bow.” Sovetsky Sport, May 2, 1980, no. 102.

“Riga Tournament Results.” Sovetsky Sport, April 4, 1982, no. 77.

Golubev, V. “Protect Talent.” Sovetsky Sport, May 28, 1982, no. 122.

“Youth Games Results.” Sovetsky Sport, July 28, 1982, no. 143. Republished in Leninskaya Smena.

“Leader — Natalya Yurchenko.” Sovetsky Sport, September 16, 1982, no. 213.

Tsvelev, S. “Yes, a Bit of a Fight in the All-Around.” Sovetsky Sport, September 17, 1982, no. 214.

“Ahead of the USA-USSR Gymnastics Meet.” Narodno Delo [Bulgaria], April 23, 1983.

“With a Premiere — in Gothenburg.” Sovetsky Sport, May 5, 1983, no. 103. [European Championships roster]

“Introducing the USSR National Team.” Sovetsky Sport, October 22, 1983, no. 242. [World Championships roster]

Dekartova, I. “Inspiration of Strength — and the Strength of Inspiration.” Sovetsky Sport, November 1, 1983, no. 250.

Bicherova, O. “These Different Faces.” Sovetsky Sport, June 30, 1984, no. 149.

Golubev, V. “Olya Continues Her Ascent.” Sovetsky Sport, December 3, 1983, no. 277.

Vladimirov, G. “All the ‘Stars’ of the Gymnastics Podium.” Sovetsky Sport, August 16, 1984, no. 188. [Friendship-84 team roster]

Shevernev, V. “This Is Top-Class!” Sovetsky Sport, August 28, 1984, no. 198.

Shachin, S. “A Sporting Autograph: Olga Mostepanova.” Smena, September 1985, no. 1400.

Avsenyev, E. “The Most Charming Mother in the World! Olga Mostepanova: I Just Love Children.” Sovetsky Sport, March 7, 1998, no. 45. [Includes editor’s note by Vladimir Golubev]

Hall of Fame Records:

“Mostepanova Ol’ga Vasil’evna.” Russian Gymnastics Federation Hall of Fame. https://sportgymrus.ru/about/chempiony/678.html

Secondary Sources:

“Olga Mostepanova: From Beautiful Beginning to Truncated End.” Rewriting Russian Gymnastics (blog), August 2013. http://rewritingrussiangymnastics.blogspot.com/2013/08/olga-mostepanova-from-beautiful.html

“Olga Mostepanova.” The Gymn Forum, biographical database. https://www.gymn-forum.net/bios/women/mostepanova.html

Appendix: The Smena Profile

Olga Mostepanova

Sergey Shachin | published in Smena, issue no. 1400, September 1985

A Sporting Autograph

In gymnastics, as is well known, official records are not kept. But what the Moscow schoolgirl Olga Mostepanova accomplished at last year’s major international competition Friendship-84 can rightfully be called a record—an absolute one. In the final, she earned four perfect scores of ten points in all four events of the all-around! Thousands of spectators in the Winter Stadium in the Czechoslovak city of Olomouc greeted the fifteen-year-old winner with thunderous applause.

Mostepanova first shone in 1980. Even then, she stunned the emotionally restrained London audience with daring, ultra-difficult combinations. “Before us is New Olya, the new Olga Korbut!” English newspapers wrote enthusiastically, evidently believing that for any young gymnast this would be the highest compliment. Yet in childhood, Mostepanova’s idol was not Korbut—as was the case for most of her peers—but Elvira Saadi, a gymnast of rare grace and poetry, world and Olympic champion, whom her teammates called Scheherazade.

It is easy to imagine how delighted Olya was when Vladimir Filippovich Aksenov, Saadi’s coach, suddenly noticed her.

Mostepanova came to gymnastics, generally speaking, by chance. Olya’s mother heard a radio announcement recruiting six-year-old girls to the Dynamo sports school and the next morning took her daughter to the stadium—simply so that the restless child might finally find an outlet for her energy. Besides, they lived not far from Dynamo, and it was convenient for the parents to take Olya to training.

Soon, the Mostepanovs moved to the opposite end of the capital, to Tekstilshchiki. Now her mother often lacked the time to accompany her daughter to the stadium. Olya began traveling alone, with several transfers. Once she got lost in the metro, burst into tears, and the stern station attendant decided to send her home. But Olya managed to persuade her to show her the way to Dynamo. She simply could not imagine missing practice. A strong sense of duty was already one of the defining traits of the young gymnast’s character.

At that time, Vladimir Filippovich Aksenov had only just moved from Tashkent to Moscow and was preparing Elvira Saadi for the 1976 Montreal Olympics—her last, as the coach knew. He had to think about new pupils. And someone among his colleagues suggested that Aksenov take a closer look at Mostepanova.

“Olya did not stand out for her looks,” the coach recalls. “But she was sharp, mobile, strong—and excessively mischievous. I wondered how to talk to her. Saadi came to me at twelve, already an ‘adult’ athlete by gymnastics standards. This one was a complete little girl. I decided to speak to her like an adult, to set her immediately on serious work. If she understood—fine; if not—I would look for another pupil. Olya understood me.”

This, however, did not mean that under the influence of a strict coach, Olya had to radically change her character and become an overly proper, obedient child. No—after training, among her friends, she was still fond of mischief and is known on the national team as a great prankster. But in the gym, at practice, Mostepanova is entirely different—calm, methodical, focused.

“Vladimir Filippovich taught me to treat any work with respect—whether gymnastics, school studies, or anything else,” Olya says. “And I am endlessly grateful to him for that. When you have a real, big goal and a firm desire to achieve it, life becomes much more interesting.”

Even the coach was often amazed by young Olya’s hunger for work. The usual training time was never enough for her. To this day, returning home, she drags a mattress off the bed onto the floor and practices saltos on it. It is no wonder that when Dynamo established the Saadi Cup for the youngest gymnasts, its first winner was Mostepanova. That day, Vladimir Filippovich thought: perhaps this new pupil could go even further than the previous one. And he proposed:

“Let’s try to combine in your gymnastics the complexity and risk that distinguished Korbut with the poetic beauty of Saadi. Can you imagine what kind of fusion that might create?”

They worked long and hard.

“We tried to ensure that my performance created a sense of flight,” Olga explains. And in October 1983, in Budapest, debuting at the World Championships, she immediately soared onto the podium.

At that championship, a fierce contest unfolded on the podium among the leader of the Soviet team, Natalya Yurchenko from Rostov-on-Don, the famous Maxi Gnauck of the GDR, and the Romanian Ecaterina Szabó. Mostepanova, however, was not taken seriously by anyone: in gymnastics, as in figure skating, judges are rarely generous to newcomers and are in no hurry to award them high marks. But… On the balance beam—one of the most treacherous apparatuses—both Gnauck and Szabó stumbled, unable to cope with their nerves. Before Olga, unexpectedly, a chance at silver flashed—but only if she could “get through” the beam with a 9.9. Olya tuned herself for a long, very long time. And she got the required score! Moreover, she was the first in the world to perform an ultra-difficult combination now officially known as the “Mostepanova connection.” Yurchenko—first. Mostepanova—second. That is how the Budapest Championships ended. And nine months later, at the tournament in Olomouc, Olga overtook Natalya as well.

Aksenov maintains that his pupil has a mathematical cast of mind. Olga truly expends her energy very rationally in training and quickly masters new programs. She herself notes that this often rescues her in difficult situations.

“That’s what happened, for example, at Friendship-84,” the gymnast recalls. “During warm-up before the all-around, I unexpectedly fell from the beam. And a couple of minutes later, I had to compete—there was no time to repeat the exercise and figure out what the mistake had been. So I mentally took the routine apart piece by piece, found the error, and at the same time focused and calmed myself. And I got a ten!”

But alongside the mathematician in Olya lives a lyricist. And therefore her gymnastics is not only astonishingly difficult, but also inspired. Many fans surely remember her beautiful floor routine to “Granada” performed by the James Last Orchestra, which earned a gold medal at Friendship-84. And at a prestigious international tournament in Barcelona, local spectators applauded Olga for a long time, saying that before her no one had managed to express so vividly on the gymnastics floor the character and color of Spanish dance.

Recently, for her great achievements in sport, the fifteen-year-old gymnast Olga Mostepanova was awarded the Order of the Badge of Honor.

“Difficulty in today’s gymnastics, of course, plays a major role,” Olga notes. “But in the pursuit of breathtaking tricks, one must never sacrifice the artistic side of the routines. My coach and I stand for beautiful, inspired gymnastics.”

It is exactly such gymnastics that we hope to see from Olga at the upcoming World Championships, which will take place in November in Canada.

More on Age