In early January 1993, the International Gymnastics Federation announced a decision that was unprecedented in the sport’s history: the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s women’s gymnastics team would be banned from that year’s World Championships in Birmingham. The reason? The federation had entered Kim Gwang Suk into international competition with three different birthdates—October 5, 1974, at the 1989 World Championships; February 15, 1975, at the 1991 Worlds; and February 15, 1976, at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics.

“This is not a case of doping, and under no circumstances is she guilty,” FIG Secretary General Norbert Bueche told reporters in Geneva. “The dates of birth were deliberately falsified by the association. Such actions cannot be tolerated.”

Kim Gwang Suk’s case marked the first time the FIG had publicly exposed and sanctioned age falsification in elite gymnastics, though the practice was widely suspected to have occurred for years. The case revealed both the lengths to which some federations would go to gain a competitive advantage and the challenges international sports bodies faced in enforcing their own age eligibility rules.

Thirty years after Kim Gwang Suk’s competitive career ended, her life is still a mystery. What survives are fragments: competition reports, newspaper descriptions, brief quotations filtered through translators—almost all produced outside North Korea. This essay follows the traces she left on the international stage between 1989 and 1993, as recorded by foreign journalists and officials, and concludes by examining the narrow but consequential precedent her case set for how the FIG would confront age falsification in the years that followed.

1989: Early Appearances

Kim Gwang Suk first appeared on the international stage at the 1987 Druzhba competition among Eastern Bloc countries. There, she tied for third on uneven bars with Hungary’s Henrietta Ónodi, the Soviet Union’s Yulia Kut (URS), and Romania’s Eugenia Popa (not Celestina, for whom the Popa is named).

But the first journalistic fragments I found come from the 1989 Asian Junior Gymnastics Championships in Beijing. Chinese head coach Gao Jian, interviewed by Xinhua News Agency after the competition, singled her out among the emerging talent: “North Korea’s Kim Gwang-suk performed a giant swing with a 540-degree turn connected to a front salto [Jaeger] on the uneven bars.” He noted that while the North Korean team was “quite strong,” they were “plagued by too many mistakes.”

Later that year, at the 1989 World Championships in Stuttgart, North Korea’s women’s team finished seventh. Kim, competing with a registered birthdate of October 5, 1974—making her officially 15 years old—placed fourteenth in the all-around competition. Some international observers took notice. A Slovak reporter covering the championships for Pravda noted the “significant progress” made by gymnasts from China and North Korea, “especially Fan Di and Kim Gwang-suk on the uneven bars,” though he observed that “their floor choreography still lags behind.”

1990: Rising Star

By the 1990 Beijing Asian Games, Kim had begun attracting significant attention from the Asian press. The North Korean team, led by Kim and teammate Choi Kyong-hui, mounted what Chinese reporters described as “a strong challenge” to the host nation. Both Kim and Choi scored 9.9 on the uneven bars, helping North Korea finish just 1.7 points behind China to claim the silver medal with a score of 195.075. South Korea took bronze.

Kim finished third in the women’s all-around final—a performance that prompted Chinese team leader Qian Kui to warn reporters: “Although China won the title tonight, we made quite a few mistakes. North Korea has made rapid progress and will be a strong opponent for China in the future.”

The South Korean press described Kim as 15 years old. If she had used the same birthdate registered in 1989—October 1974—she would have been 16 in September 1990. The discrepancy suggests the North Korean federation may have already begun manipulating her age by this point, though the change would not become publicly apparent until the following year.

South Korean newspapers also captured the friendlier atmosphere between North and South Korean gymnasts at the Beijing Games, contrasting it with later encounters. After the team competition, Kim and South Korea’s Park Ji-suk appeared together at a press conference, “linked arms affectionately, displaying the friendship and shared ethnic bond they had built through training halls and international competitions.” Park, 18, told reporters that Kim “feels like a younger sister,” while Kim noted they had first met at the 1989 World Championships in Stuttgart.

1991: The World Stage

The 1991 World Championships in Indianapolis marked Kim’s breakthrough—and the moment when serious questions about her age erupted into public view. Competing with a new registered birthdate of February 15, 1975, she won the gold medal on uneven bars with a perfect 10.0 score.

Her routine was extraordinary. International Gymnast magazine described it in detail: “She began with a Tkatchev-Xiao combination, continued with a blind-full pirouette to Jaeger, and swung a buttery-smooth giant-full to tucked double flyaway.” Five of the six judges awarded her a perfect 10.0; the sixth gave her 9.95. When the high and low scores were dropped, four perfect tens remained.

The crowd of nearly 16,000 spectators at the Hoosier Dome erupted. Yugoslav newspapers reported that “experts are assessing her routine as something truly perfect, something that has not been seen before at gymnastics competitions,” comparing her performance to Olga Korbut’s legendary showing at the 1972 Munich Olympics.

The Indianapolis Star described her as “every bit the Korean doll at 4-feet, 4-inches and 60 pounds,” noting that she “would not look the reporters in the eye but, instead, gazed downward at the gold medal that now hung around her neck.” When asked how she felt about winning, she replied through a translator: “It is like I am flying in the sky.”

But even as the crowd gave her repeated standing ovations, prominent voices were raising concerns. Béla Károlyi, the legendary and divisive U.S. women’s team coach, was direct in his assessment: “I don’t believe she is the 17-year-old the Koreans present her as. Her milk teeth are falling out, which is a good indication she’s not even 11.” Nonetheless, Károlyi had to admit, “She did a great performance. She deserved the highest scores.”

Kim’s coach insisted she had lost the tooth by hitting one of the bars during practice—the same explanation that would be repeated whenever journalists noticed the gap in her smile.

1992: Barcelona and After

At the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, Kim competed with yet another birthdate—February 15, 1976. This third variation would later become the smoking gun in the FIG’s investigation. Under the 1976 birthdate, Kim met the Olympic eligibility rule, which required women to turn 15 during the calendar year of the Games.

In the lead-up to the Olympics, Japanese media interviewed Kim, who left little room for ambiguity. “I’m going to take first place,” she declared. The confidence was unmistakable; the outcome less kind. Her routine closely mirrored the one she had performed in Indianapolis. As International Gymnast observed, “The rest of the routine was just like Indy’s winning set, complete with Tkatchev to Xiao Ruizhi and 1½ pirouette to Jaeger.” The major change was a new double-layout dismount, and it proved costly. Kim stepped forward on the landing, enough to push her off the medal stand.

International Gymnast could not resist a final aside: “Kim, whose age is still a big question mark, isn’t getting older—just better.”

Questions about Kim’s age intensified after the Barcelona Games. Hans-Jürgen Zacharias, Vice President of the German Gymnastics Federation (DTB) and a member of the FIG, publicly noted the discrepancies in an October 1992 interview with Sport Bild: “In the case of the 1991 world champion on the uneven bars, Kim Gwang Suk of North Korea, three different dates have been recorded: in 1989 it was said that she was born on 15 February 1974, in 1991 on 15 February 1975, and in 1992 on 15 February 1976. Examples like this prompted the DTB to raise the minimum competition age from 15 to 16.” (His birthdates differ from those that the FIG published in its Bulletin.)

The question remains: Why had no one acted on these suspicions during the 1991 World Championships? Concerns about Kim’s age were already circulating, and she had been entered using two different birthdates. Wasn’t that a sign that something was amiss?

In 1991, responsibility for age control formally rested with the FIG’s Women’s Technical Committee, then chaired by Ellen Berger. In a 1993 interview about Kim’s case, Berger emphasized that the committee had acted according to its procedures. “Our women on the technical committee were very conscientious at the time in checking the passports of all competitors,” she recalled. “Since passports are state documents, we must give credence to the information entered in them.”

Berger’s explanation illuminates the limits of the system. The committee verified the passport in front of them, but did not cross-reference those documents against prior championships. As a result, Kim’s 1991 passport, listing a February 15, 1975 birthdate, raised no procedural alarm, even though FIG records from Stuttgart in 1989 had listed a different birthdate.

1993: The Ban

The FIG announced its decision in January 1993. The Swiss newspaper Le Nouvelliste quoted Secretary General Norbert Bueche explaining the discovery: “During a routine passport check for the Birmingham championships, it was found that Kim Gwang-Suk had been registered with three different dates of birth at the 1989 and 1991 World Championships and at the Barcelona Olympic Games.”

Secretary General Norbert Bueche’s statement was carefully worded to distinguish between institutional wrongdoing and individual culpability. “It is a most unsportsmanlike behavior and unfair to all other participating nations and gymnasts,” read the FIG’s official release. But Bueche made clear that Kim herself bore no responsibility for the falsified documents, stating, “Under no circumstances is she guilty. The dates of birth were deliberately falsified by the association.”

According to the North Korean federation, Mrs. Li Jong-Ae was the only person who knew Kim’s real age, which the FIG’s executive committee found hard to believe. The person responsible for the mistake was dismissed.

The Guardian, reporting on the ban, noted the broader pattern of concern: “Gymnastics is watched by a suspicion that ambitious coaches are asking young female exponents to bend unformed bodies into phenomenal feats which may cause lasting deformity.” The newspaper laid out the timeline of Kim’s three birthdates and observed tartly: “She had hardly grown, still had missing teeth (an asymmetric bars accident, said her coach) and won the bars gold.”

The timing of the FIG’s first major age falsification case coincided with significant organizational changes in international gymnastics. Ellen Berger, the longtime head of the Women’s Technical Committee and a prominent figure from the East German gymnastics establishment, had stepped down. Jackie Fie of the United States became the new head of the Women’s Technical Committee.

Whether the change of leadership contributed to the FIG’s willingness to investigate and sanction age falsification remains a matter of speculation. What is certain is that this marked the first time the federation publicly acknowledged and punished such practices, despite longstanding rumors that several countries had been entering underage athletes for years.

1993: The East Asian Games

Despite the World Championships ban, North Korea chose to send Kim Gwang Suk to compete at the East Asian Games in Shanghai in May 1993. South Korean newspaper Donga reported that Kim, “the 1991 world champion,” had “undergone intensive training in order to fully demonstrate her abilities at this competition.”

The atmosphere between North and South Korean gymnasts had changed dramatically since the warmer interactions of 1990. When both teams trained at the Shanghai Gymnasium on May 7, South Korean reporters noted that “instead of the expected mutual greetings or friendly gestures, there was a conspicuous effort to avoid one another, creating an overall chilly atmosphere.” Kim and her teammates “did not readily respond to poses requested by South Korean photojournalists and focused solely on training.”

North Korea’s team finished second behind China. Kim placed fourth in the all-around and tied with China’s Luo for the gold medal on uneven bars—a symbolic victory that demonstrated her continuing prowess on her signature apparatus despite the controversy.

Later in 1993, the North Korean government issued a commemorative stamp featuring Kim’s portrait alongside those of other prominent North Korean athletes. The stamp depicted “portrait photographs of the athletes, along with the North Korean flag, medals won, and scenes from competition as background imagery,” according to South Korean newspaper Chosun Ilbo.

Kim’s Precedent

Following the East Asian Games, North Korea’s women’s team vanished from the World Championships start lists. Whether that disappearance reflected lingering fallout from the 1993 sanction, internal federation policy, or other pressures remains unclear.

What was clear was the precedent Kim Gwang Suk’s case established—though it was a narrow one. The FIG demonstrated that it could investigate and punish age falsification, but only under the most extreme conditions. Three different birthdates across three major competitions made denial impossible: no athlete could have been born three times. Short of such internal contradiction, suspicion—whether based on appearance, rumor, or inconsistencies in national vs. international start lists—had never been sufficient to compel action. Enforcement began not with doubt, but with documentary contradiction within the FIG’s own filing cabinets.

When pressed to clarify her age, the North Korean federation ultimately settled on February 15, 1975, expressing “regret” over the earlier discrepancies. That chronology would have made Kim fourteen in Stuttgart, sixteen in Indianapolis, and seventeen in Barcelona. Yet viewed in retrospect—against years of documented manipulation by the North Korean federation—even this resolution carries limited authority. It closes the file without restoring certainty.

Kim was not the first gymnast whose age was falsified, and she would not be the last. She was simply the first case in which the deception became so blatant that the FIG had to publicly expose it, formally acknowledge it, and sanction it, forcing the sport to confront a practice it long suspected and had long tolerated. In doing so, the FIG established not a safeguard, but a threshold—one so high that only the most extreme cases would ever cross it.

Kim Gwang Suk’s Registered Birth Dates and Competition Ages

| Competition | Birthdate Listed | Age at Competition |

| 1989 World Championships | October 5, 1974 | 15 |

| 1990 Asian Games | Unknown | 15 |

| 1991 World Championships | February 15, 1975 | 16 |

| 1992 Olympic Games | February 15, 1976 | 16 |

| 1992 Chunichi Cup | February 15, 1975 | 17 |

References

1989

“Asia’s Gymnastics Reserve Forces Are Improving: Coach Gao Jian Reviews the Asian Junior Gymnastics Championships.” People’s Daily (人民日报), April 24, 1989, p. 4.

Bučko, Andrej. “A Dignified Silver Jubilee. For Whom, and How…” Pravda, October 26, 1989, No. 253.

1990

“Gymnastics All-Around: Five Red Flags Raised.” People’s Daily (人民日报), September 26, 1990, p. 2.

“No Longer the Host’s Exclusive Stage—Watch the Contenders Flex Their Might from All Sides.” People’s Daily (人民日报), September 25, 1990, p. 2.

“Gymnastics: Park Ji-suk and Teammates Fight Hard, but Fall Short of Japan; North Korea Finishes One Point Ahead, Silver Slips Away.” Chosun Ilbo (조선일보), September 25, 1990, p. 11.

“At the Wrestling Arena, the National Anthem Played Four Times… They Were Busy Just Playing It: Park Ji-suk and Kim Gwang-suk Share Sisterly Affection as ‘North–South Gymnastics Sisters.'” Chosun Ilbo (조선일보), September 26, 1990, p. 10.

1991

“On the first day of the apparatus finals…” Kurír—reggeli kiadás, September 16, 1991, No. 254.

“Nearly 16,000 spectators gathered at the Hoosier Dome…” Népszabadság, September 16, 1991, No. 217.

“World Championships in Gymnastics: Never before seen…” Politika, September 16, 1991, No. 27998.

“World Championships in Gymnastics: Outstanding Korean gymnast Kim Gwang Suk (15) from North Korea amazed experts…” Borba, September 16, 1991, No. 260.

Benner, Bill. “‘Little Korean doll’ flies to gold medal.” The Indianapolis Star, September 15, 1991, p. 20.

“Korean sprite steals gymnastics show: Zmeskal.” The Cincinnati Enquirer, September 15, 1991, p. 28. Associated Press.

“‘There is no sex in the States…'” Sovetsky Sport (Советский Спорт), October 3, 1991, No. 191.

“North Korean Interrupts Soviet-Romanian Gold Rush.” International Gymnast, December 1991.

1992

“Two More 10.0s for Women, Four More Golds for Scherbo.” International Gymnast, October 1992.

“Aged Up Twice: Kim Gwang Suk of North Korea.” Sport Bild, October 14, 1992, No. 43.

1993

“Gymnastics—expulsion.” Le Nouvelliste (Switzerland), January 7, 1993, p. 12. Reuters.

“North Korean Gymnastics Star Kim Kwang-suk Involved in Age Falsification: Barred from World Championships.” Chosun Ilbo (조선일보), January 7, 1993, p. 25. AFP-Yonhap.

“North Korea’s Gymnasts Must Stay at Home.” Berliner Zeitung, January 8, 1993, p. 12.

“Korea girls prove gymnastic with their dates of birth.” The Guardian, January 30, 1993, p. 15.

“Kim Gwang Suk: How Old Is She Really?” USA Gymnastics Magazine, March/April 1993, Volume 22.2.

“At the 1st East Asian Games, North Korea Emerges as a Strong Dark Horse.” Donga (동아일보), May 8, 1993, p. 23. Yonhap.

“South and North Korean Gymnasts Treat Each Other Coldly When Face to Face.” Donga (동아일보), May 9, 1993, p. 17.

“Stamps Issued Featuring Athletes’ Faces.” Chosun Ilbo (조선일보), September 22, 1993, p. 23.

Appendix A: The FIG Bulletin

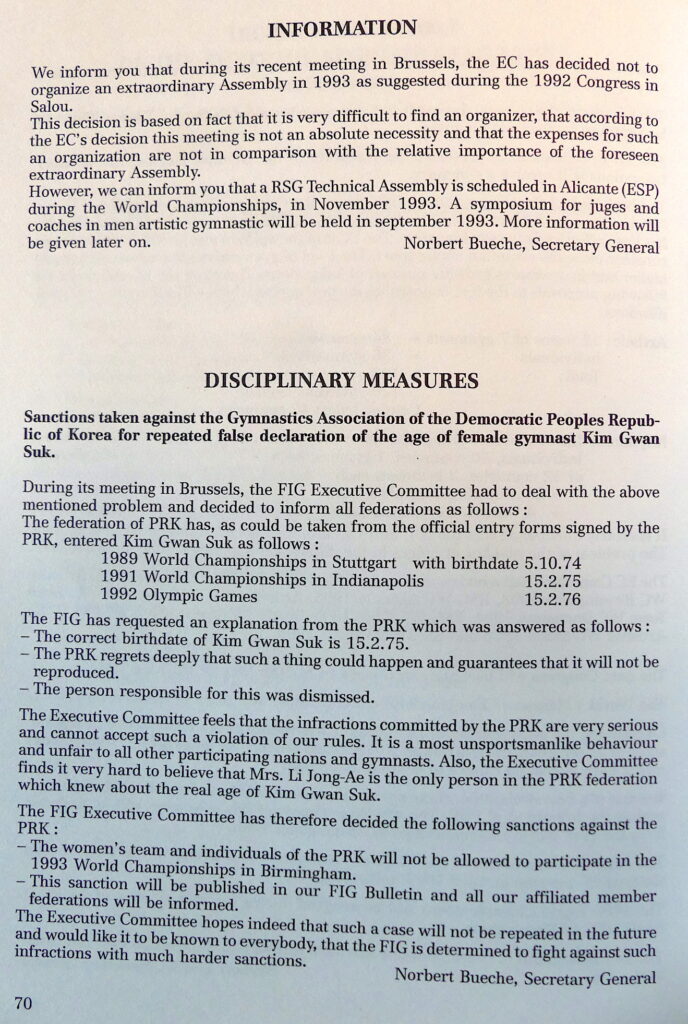

DISCIPLINARY MEASURES

Sanctions taken against the Gymnastics Association of the Democratic Peoples [sic] Republic of Korea for repeated false declaration of the age of female gymnast Kim Gwan Suk.

During its meeting in Brussels, the FIG Executive Committee had to deal with the above mentioned problem and decided to inform all federations as follows :

The federation of PRK has, as could be taken from the official entry forms signed by the PRK, entered Kim Gwan Suk as follows :

1989 World Championships in Stuttgart with birthdate — 5.10.74

1991 World Championships in Indianapolis — 15.2.75

1992 Olympic Games — 15.2.76

The FIG has requested an explanation from the PRK, which was answered as follows:

– The correct birthdate of Kim Gwan Suk is 15.2.75.

– The PRK regrets deeply that such a thing could happen and guarantees that it will not be reproduced.

– The person responsible for this was dismissed.

The Executive Committee feels that the infractions committed by the PRK are very serious and cannot accept such a violation of our rules. It is a most unsportsmanlike behaviour and unfair to all other participating nations and gymnasts. Also, the Executive Committee finds it very hard to believe that Mrs. Li Jong-Ae is the only person in the PRK federation which knew about the real age of Kim Gwan Suk.

The FIG Executive Committee has therefore decided the following sanctions against the PRK :

– The women’s team and individuals of the PRK will not be allowed to participate in the 1993 World Championships in Birmingham.

– This sanction will be published in our FIG Bulletin and all our affiliated member federations will be informed.

The Executive Committee hopes indeed that such a case will not be repeated in the future and would like it to be known to everybody, that the FIG is determined to fight against such infractions with much harder sanctions.

Norbert Bueche, Secretary General

FIG Bulletin, March 1993

Appendix B: Ellen Berger’s Comments on the Kim Case

“North Korea’s gymnasts must stay at home”

World champion Kim Gwang-Suk with false age information

The artistic gymnasts from North Korea have been excluded from the World Championships in April in Birmingham following a decision by the International Gymnastics Federation (FIG). As the basis, Swiss FIG General Secretary Norbert Bueche cited the repeatedly discrepant birth dates in the passport of World Champion Kim Gwang-Suk, who won gold on uneven bars at the 1991 Championships in Indianapolis.

A routine check of passport entries for starting permission in Birmingham had now revealed that Kim Gwang-Suk had submitted three different age specifications both at the Barcelona Olympics and at the last two World Championships in Indianapolis and Paris. Bueche commented yesterday: “Although no doping case is present here, such a blatant falsification cannot go unpunished.”

The Technical Committee for Women within the World Federation is responsible for age control of female gymnasts at World Title competitions. In 1991, in September in the Hoosier Dome in Indianapolis, at the World Championships, the chair of the Technical Committee was still Ellen Berger, President of the East German Committee. Ms. Berger, who had stood at the head of this important body for over a decade, resigned from this position shortly before Barcelona for reasons of age. She was subsequently elected Honorary Vice President of the FIG. She recalled the events of Indianapolis: “Back then, our women on the Technical Committee very conscientiously controlled the passports of all state documents. Since the passports are state documents, we must give credence to the information in the passport.”

As Ms. Berger only learned after the latest revelations, the specifications of the later uneven bars World Champion from North Korea in 1991 had been changed by a gymnastics official from North Korea.

Kim Gwang-Suk shone at the time in the giant cauldron of the Hoosier Dome and received the top score of 10.0 for her uneven bars routine…

“It is very unfortunate about the little Korean,” says Ellen Berger in retrospect, “because she is truly a very good gymnast and should not have needed such manipulations.”

The background to the entire fraud story is the international age limits for female gymnasts. In the year before Olympic Games, girls can still be 14 years old to participate in qualifications. In the Olympic year and at the Games themselves, however, they must already be 15 years old. Kim Gwang-Suk was thus most likely unjustly made eligible for participation in World Championships and also at the Barcelona Games (4th place uneven bars). No one knows exactly how old or rather how young the champion gymnast is!

The successor to Ellen Berger, who now has a difficult office in the Technical Committee, is the American Jackie Fie.

“She must, of course, proceed sharply against such fraud attempts,” says Ellen Berger.

Michael Jahn, Berliner Zeitung, January 8, 1993

Appendix C: A Japanese Profile of Kim Gwang Suk in 1992

Announcer [00:00:00] (in Japanese):

“…points to take first place. Because her preparation for the Olympics went so well, she was also able to compete in the all-around—an event she was not originally expected to enter.”

[applause]

“Kim is small in stature, and because her legs and lower body are weak, she struggles in other events such as floor exercise.”

[silence]

“But when it comes to the uneven bars, her natural upper-body strength and supple physique come into full play.”

[00:00:30]

“This is Kim’s release move, known as the Kim Gwang-suk. Because it is a difficult series of connected elements, she practices it intensively for three solid hours, over and over again.”

Kim Gwang Suk (in Korean): I’m going to take first place.

Reporter: You mean win the gold medal?

Kim Gwang Suk: Yes.

Reporter: Do you feel confident?

Kim Gwang Suk: I do feel confident, but you never really know until you actually compete.

Reporter: [00:01:00] Would you say there are any weaknesses? Anything that feels like a disadvantage?

[background conversation]

Kim Gwang Suk: No, there aren’t any. Yes.

Announcer (Japanese):

“For Kim, this is her first Olympic Games. Because her training sessions are held at night to match competition conditions, she spends the daytime resting in her room or going window-shopping to relax and change her mood.”

Coach [00:01:30] (Korean): Everyone at the competition is good, and there are many strong contenders, so there’s a lot of tension. She has already taken first place once at a major championship, so this time as well She trained hard with the determination to take first place no matter what.

Announcer (Japanese):

“This is North Korea’s first Olympic appearance in twelve years. For this small gymnast, Kim, rests the dream of becoming North Korea’s first-ever Olympic gold medalist in gymnastics.”

Appendix D: A Korean Profile of Kim Chun Phil

With an appearance by an adult Kim Gwang Suk.

[00:00:00]

[music]

Title: A female coach who shines through a life of purpose.

[00:00:30]

Kim Chun Phil:

When people think of sport, they often associate it with youth and youthfulness. That is because it requires not only strong mental fortitude, but also intellectual and physical ability to support it. To possess mental strength, intellectual capacity, and physical ability all at once is truly difficult—and for us women, it is even more difficult than for men.

At times, it becomes so exhausting that tears come, and I often think about giving up my life as a coach. But then I think, “If I cannot overcome this, how will my athletes get through their own difficult moments?” And with that thought, I find myself standing up again.

[music]

[00:01:30]

Speaker 1:

It’s really hard.

[music]

[00:02:00]

[music]

Kim Chun Phil:

This is a photograph I took with gymnast Kim Gwang Suk after she won first place at the 26th World Gymnastics Championships.

[music]

Kim Gwang Suk:

The road to success was not easy. During the days of training, the coach was truly like a tiger, and training every single day under her guidance was extremely difficult.

But when I won first place at the 26th World Gymnastics Championships, and she was happier than anyone else—when she shed tears and said, “You have made the Republic’s flag fly in the skies of America”—it was only then that I truly understood my coach, a strong woman.

[music]

Kim Chun Phil:

When athletes win competitions, the pride and joy felt by a coach are difficult to express in words.

[music]

Kim Chun Phil’s Daughter:

Because my mother is so busy with training and coaching, there are many times when she cannot come home, so I often take care of the household chores like this. When I’m alone at home, it can feel lonely, and at times I’ve felt resentful toward my mother.

But I never blamed her. Instead, I’m proud of my mother, who is respected by so many people.

More on Age