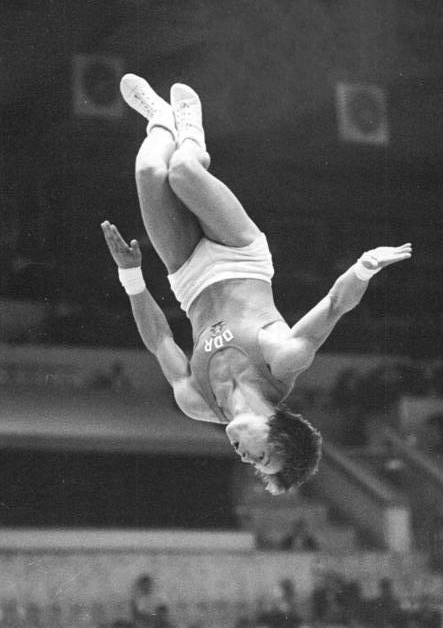

In November 1981, Ralf-Peter Hemmann stood in a packed Moscow arena, preparing for his second vault in the apparatus finals of the World Championships. His first had been flawless—a handspring front with a half twist that stuck to the mat as if pulled by a magnet. The judges awarded him a perfect 10. Now came his Tsukahara. He landed it cleanly. Score: 9.95. The twenty-two-year-old auto mechanic from Leipzig was the world champion.

“After the 10, I still wasn’t sure,” he told reporters afterward, beaming. “But then when the second vault went so well…” He didn’t finish the sentence. He was being called to the podium, where thousands of East German tourists in the sold-out hall cheered for their new champion. It was the kind of victory that makes careers, the kind that gets remembered in record books. The days before had been the hardest, Hemmann said—sleepless with nerves. But in the competition itself, he’d been completely calm.

Then, without warning, he disappeared.

Not literally—Hemmann was still alive. But his gymnastics career ended abruptly in the spring of 1982, with no explanation, no farewell interview, no public acknowledgment of what had happened. One day, he was preparing for a competition in the Netherlands. The next, a club official told him his competitive career was over, effective immediately. The press never called again.

For years, people whispered theories while the official story was buried in Stasi files that wouldn’t surface until after reunification: Hemmann had tested positive for anabolic steroids at that same Moscow World Championship where he’d won gold. The Soviets had caught him, covered it up, and allegedly used the secret as leverage against East German sports officials. Rather than face an international scandal, those officials made Hemmann himself disappear—forced into retirement with his title mysteriously intact.

Thirty years later, Hemmann still didn’t have answers. His case raises troubling questions about how Cold War sports politics may have enabled cover-ups at the highest levels. Rumors of the positive test circulated among judges even during the competition itself. Yet the positive test result was never published, and the International Gymnastics Federation never stripped him of his medal. We may never know for certain why.

Here’s a translation of Sandra Schmidt’s article on Hemmann’s case.

Doping, Harassment, and Cover-Ups

It has been 30 years since the GDR gymnast Ralf-Peter Hemmann became the world vault champion in Moscow. The title entered gymnastics history—even though, according to statements from the Moscow laboratory, he tested positive for an anabolic steroid. Hemmann was removed from gymnastics, kept his title, and, to this day, wonders what really happened back then.

By Sandra Schmidt, Deutschlandfunk, December 4, 2011

There are countless stories about the successes of GDR sports, and just as many today about athletes who were systematically doped and harmed. But the story of the gymnast Ralf-Peter Hemmann is entirely different—and it reveals, more clearly than anything else, the power held by the sports officials.

Official GDR historiography records the following: the Dresden-born Hemmann won bronze at the 1978 World Championships and team silver at the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games. In 1981, he became the world champion on vault. In spring 1982, he ended his career.

Hemmann recalls the evening after his victory:

“A huge weight fell off everyone’s shoulders. We were desperate to win that medal, and then we had it, and managed to break into the phalanx of the two Soviet athletes — and of course, doing that in the lion’s den made it all the better.”

But there is a second version of the story. In a meeting report by IM Technik, the code name for Manfred Höppner—the GDR’s chief sports physician, who in 2000 was convicted of distributing doping substances, including to minors, and received a suspended prison sentence—the following appears under the heading Hemmann:

“During the visit of a DTSB leadership delegation to the USSR in January 1982, Comrade Ewald was informed privately by Comrade Pavlov that a positive test result had been recorded for a GDR gymnast at the gymnastics world championships in Moscow. […] No report was submitted to the International Gymnastics Federation, but according to Comrade Ewald, this meant that the Soviet Union now had leverage over us. What was essential, however, was that our Party leadership not learn of it; he had given his promise that such a thing would not happen to GDR athletes.”

[Note: After the 1977 European Cup, where Ilona Slupianek tested positive, it was decided that every athlete would henceforth be required to provide a urine sample before leaving the country for an international competition, to be analyzed in the Zentrale Doping-Kontroll-Labor in Kreischa. So, it would have been surprising that there was a positive sample.]

Hemmann knew nothing of this at first. After the World Championships, he recovered from an injury, advanced his training as an auto mechanic, and prepared for the coming season. Despite constant pressure, he still had not joined the SED.* In spring 1982, he told a newspaper he was looking forward to his first appearance after the World Championships, planned at a tournament in the Netherlands:

“Then the day came when I was supposed to travel to the Netherlands with my coach. We went to our club’s training center to see our club chairman, and he told me very plainly that, effective immediately, my elite sports career was over.”

[Note: This means that he had not joined the Socialist Unity Party of Germany, the ruling communist party of East Germany. In elite sports, this would have been strongly encouraged or informally expected.]

Hemmann’s personal coach, Gerd Falkenstein, suddenly found himself without his best athlete:

“They didn’t even ask me! He was out in no time—and that’s how it was, decisions like that in GDR sports happened very quickly, bang, just like that, practically overnight.”

Manfred Höppner had already traveled to Moscow in early February 1982 for the opening of the B-sample. His report:

“The finding for the gymnast Hemmann was clearly positive. The substance in question is not permitted in GDR elite sports. Comrade Ewald has reserved the right to speak with Hemmann himself. If Hemmann acted on his own initiative, he will be relieved of his performance duties; otherwise, the federation doctor, Dr. Fröhner, will be held responsible.”

[Note: In doping control, an athlete’s urine or blood sample is split into two parts: the A-sample and the B-sample. The A-sample is analyzed first; if it shows a prohibited substance, the result is considered provisional. The athlete then has the right to request the opening and testing of the B-sample—a safeguard to confirm the result and rule out lab error, contamination, or mishandling before any sanction becomes official.]

Ralf-Peter Hemmann remembers his conversation with DTSB President Ewald well. Ewald pressured him, claimed he had acquired and injected the substance himself, and told him it was a “political decision.” For Hemmann:

“… it was a shock, and I have to be honest, I still haven’t really gotten over it. […] I always felt like someone who’d been in prison despite being innocent, and suddenly nobody wanted much to do with you anymore — that’s quite a blow.”

The world champion received an official farewell, including a medal and a small payment for his achievements. Then came his military conscription, after which he was offered a job working with young gymnasts at the sports club. Only the press never called again:

“It was completely hushed up, and of course that left much more room for all kinds of rumors and speculation, because obviously no one could imagine why he suddenly stopped.”

The federation doctor at the time, Gudrun Fröhner, knew the circumstances of his retirement. She calls the case “tragic” today. Back then, she traveled with Hemmann to see Manfred Ewald in Berlin, but she herself was not given a meeting.

“It was such awful psychological terror—it was terrible, and most of all, because I felt so sorry for the boy.”

She is absolutely convinced of Hemmann’s innocence, and when asked whether she had administered banned substances to him, Fröhner reacts with firm insistence:

“Never! Never! Never! Out of the question! I swear, never!”

Ralf-Peter Hemmann does not believe his doctor was at fault. None of the known files suggests otherwise. The GDR sports leadership gave those involved an explanation for the inexplicable events. Coach Gerd Falkenstein:

“What people said at the time was that the GDR had somehow exposed some Soviet athletes in winter sports, and that this was payback.”

A clever version—because according to it, no one in the GDR is to blame. But like all the other statements, it has neither been proven nor disproven to this day. This version also brings the FIG, the International Gymnastics Federation, into play. Why did it not strip Hemmann of his medal and award it to the second-place Soviet gymnast, Akopian?

Contrary to Höppner’s claim, word of the positive test by a GDR gymnast was already circulating during the competitions in Moscow. An American eyewitness recalls that all the judges on site knew about it. And one of the East German judges from that time confirms today that the “rumor” was already going around in Moscow. It’s reasonable to assume that the FIG president at the time, the Russian Yuri Titov, had no interest in a doping scandal—especially one involving an athlete from a socialist brother nation. That makes a deal between him and the head of the superior judging panel, Karl-Heinz Zschocke of the GDR, seem entirely plausible.

The FIG responded rather curtly that its archives go back only twenty years. Yet it was in 1982—the very year after the Hemmann case—that it established a medical commission. None of this helps Ralf-Peter Hemmann. He is still waiting for answers.