As Arthur Gander said during the technical committee meeting, “Finally, gentlemen, a gymnast who shows a routine with none of the elements of risk, originality, and difficulty should never win a world championship.”

Let’s dive into the 1966 World Championships and see if Gander’s words came true.

This is a long post, so here are a few links to help you jump around.

Historical Context | Gymnastics Context | Video Footage | Team Competition | All-Around Competition | Event Finals

Gymnasts: 143 gymnasts

Tuesday, September 20: Opening Ceremonies

Wednesday, September 21: Compulsories

Friday, September 23: Optionals

Sunday, September 25: Event Finals

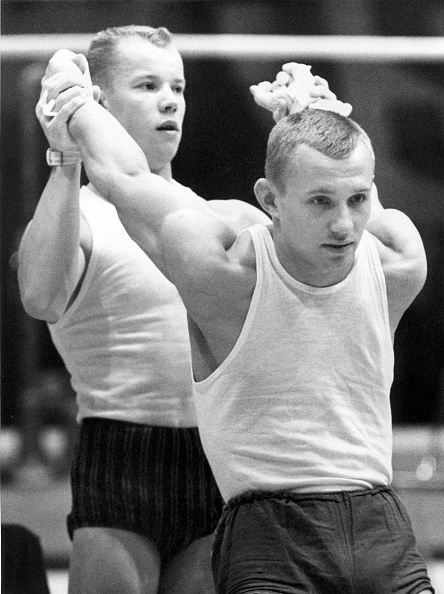

Photo: Diomidov (L) and Voronin (R), Getty Images

Historical Context

Gymnastics doesn’t happen in a vacuum. So, here’s some information to get you situated.

Japan

- Typhoons Helen and Ida landed in Japan in late September, coinciding with the end of the World Championships.

- The Sanrizuka Struggle: Civil conflict over the location of Tokyo’s next airport erupted.

- Sadly, plane crashes were common: All Nippon Airways Flight 60 (Feb.4), Canadian Pacific Air Lines Flight 402 (Mar. 4), BOAC Flight 911 (Mar. 5), All Nippon Airways Flight 533 (Nov. 11)

The Space Race between the USSR and the USA continued.

- The Soviet Union landed Luna 9 on the Moon

- The Soviet Union’s Luna 10 became the first spacecraft to orbit the Moon.

- Lunar Orbiter 1 was the first U.S. spacecraft to orbit the Moon.

The Vietnam War raged on, and so did the protest movement.

- March 25-26: the National Coordinating Committee to End the War in Vietnam helped sponsor the “Second International Days of Protest.”

- On April 12, 1966, 29 B-52s bombed Northern Vietnam, trying to break the supply line that was nicknamed the “Ho Chi Minh Trail.”

- On July 3, protesters demonstrated against the U.S. war in London outside the U.S. Embassy.

- On July 7, the European Communist nations agreed to send volunteers to North Vietnam if the North Vietnamese government requested such support. The nations included were the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania.

Civil unrest and mass racial violence were boiling over in the United States.

- Examples: the Hough riots in Cleveland, the Division Street riots and the Marquette Park riot in Chicago, and the Hunters Point riot in San Francisco

- Compton’s Cafeteria riot in San Francisco was one of the first LGBTQ+-related riots

Not your type of history? Here’s some more information…

- Star Trek and Batman debuted on TV.

- The Australian dollar was introduced on February 14, 1966, officially replacing the Australian pound.

Gymnastics Context

Don’t remember what was happening leading up to the World Championships? No problem. Here’s what you need to know…

Reigning Olympic Champions (1964)

- Japan (Team)

- Endo Yukio (AA)

Reigning European AA Champion (1965)

- Franco Menichelli (57.55)

- He defeated Viktor Lisitsky (57.50) and Sergei Diomidov of the USSR (56.95)

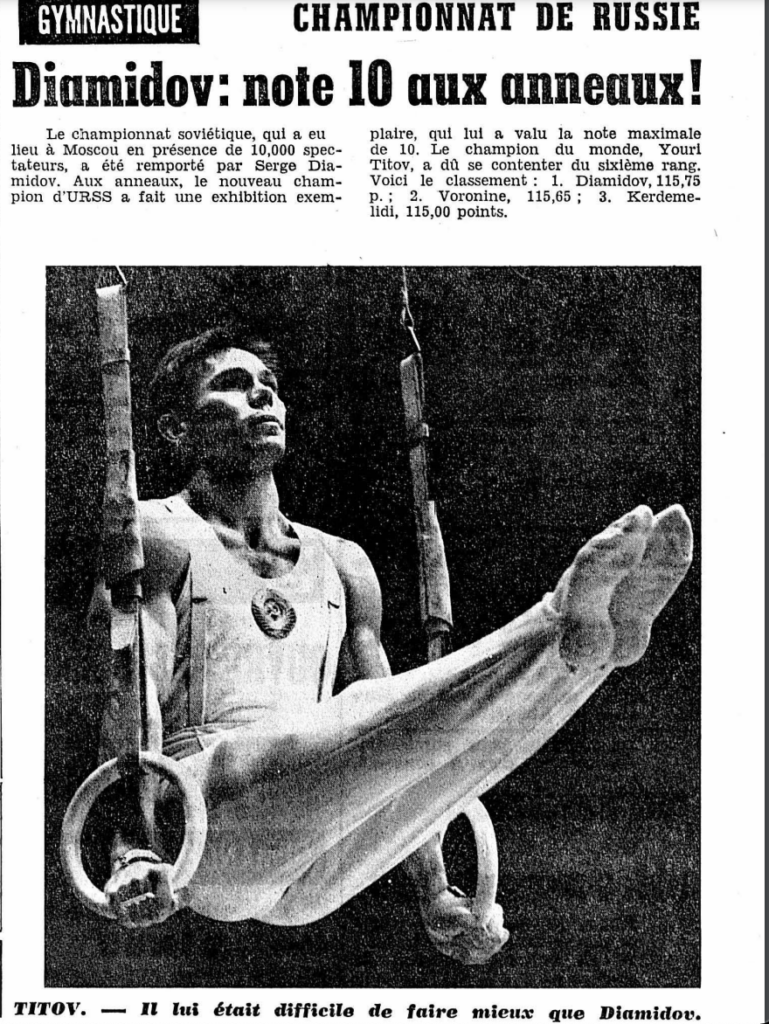

Recent Soviet National Results

- The Gist: It was a tight race between Lisitsky, Voronin, and Diomidov for Soviet supremacy

- 1965 Soviet Nationals – June 1965

- 1. Viktor Lisitsky (116.30) 2. Sergei Diomidov (115.55) 3. Viktor Leontiev (114.30)

- Medvedev scored a 10.0 on parallel bars

- 1965 Soviet Nationals – November 1965

- 1. Mikhail Voronin (115.0) 2. Sergei Diomidov (114.65) 3. Valery Kerdemelidi (113.0)

- During the Soviet Nationals, Diomidov scored a 10.0 on rings.

- 1966 World Championships Qualifications – July 1966

- 1. Sergei Diomidov (116.45) 2. Viktor Lisitsky (115.15) 3. Medvedev (114.10)

Note: The rank order in this article is the same as what Modern Gymnast reported, but the all-around scores in this article differ from those reported by Modern Gymnast.

Recent Japanese National Results

- The Gist: Endo was still the gymnast to beat, but Nakayama was making a name for himself.

- 1964 Japanese Nationals – November 1964

- 1. Endo Yukio (116.70) 2. Tsurumi Shuji (115.70) 3. Hayata Takuji (115.65)

- 1965 Japanese Nationals – November 1965

- 1. Endo Yukio (115.50) 2. Nakayama Akinori (114.45) 3. Tsurumi Shuji (114.35)

- 1965 Japanese Qualifications for Worlds – July 1965

- 1. Endo Yukio (115.25) 2T. Nakayama Akinori and Kato Takeshi (114.25)

In Other News

- Nakayama Akinori won the Universiade in 1965 with a 58.80.

- In a dual meet between Japan and the USSR, Diomidov won the all-around (58.20). Mikhail Voronin was second (58.00), and Tsurumi Shuji was third (57.90).

For what it’s worth, the Italian newspaper L’Unità had picked:

- Japan and the Soviet Union as the top teams at Worlds

- A race for bronze between East Germany, Poland, and Italy

- Endo Yukio as the World all-around champion

Arthur Gander made it clear that risk and originality were the path to win World Championship titles.

- He said, “Finally, gentlemen, a gymnast who shows a routine with none of the elements of risk, originality and difficulty should never win a world championship.”

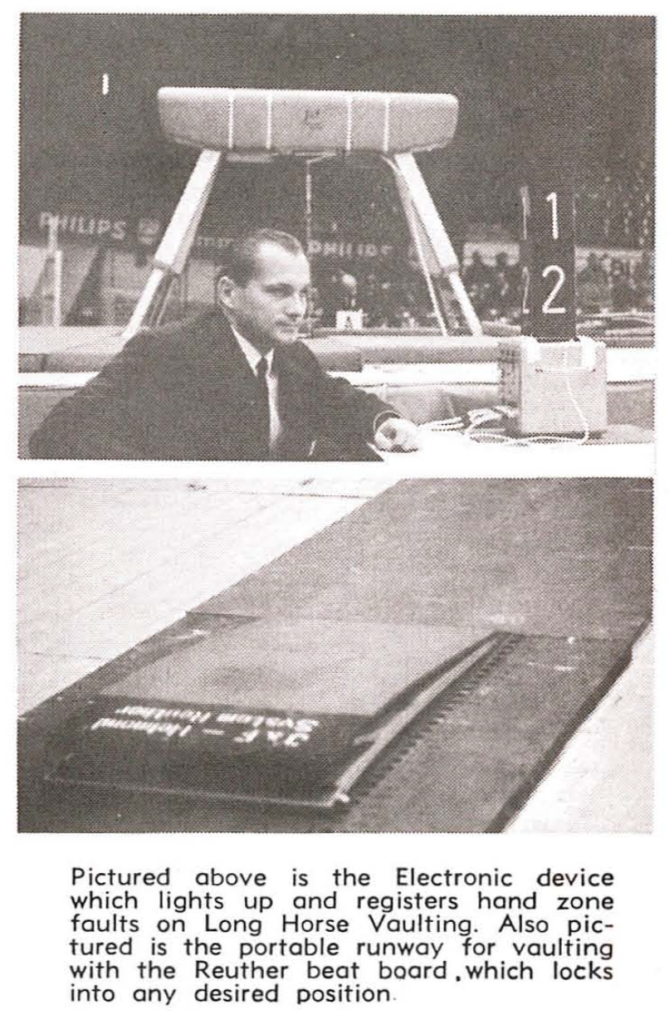

Judging robots: There were judging robots, which evaluated where the men placed their hands on the vaulting horse. (Certain vaults required your hands to be placed in different locations.)

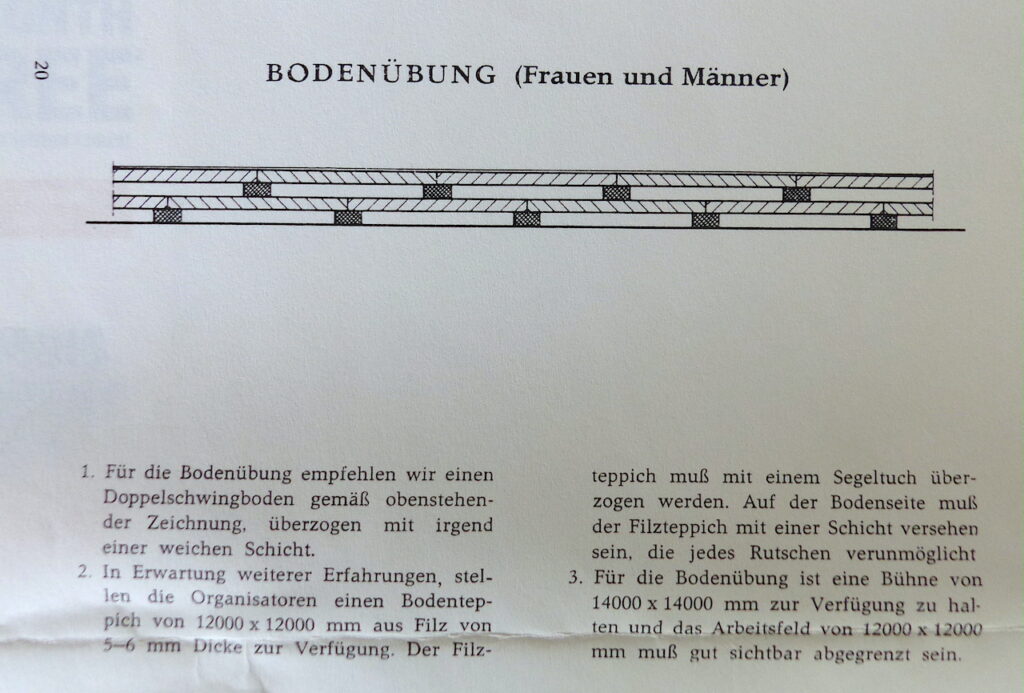

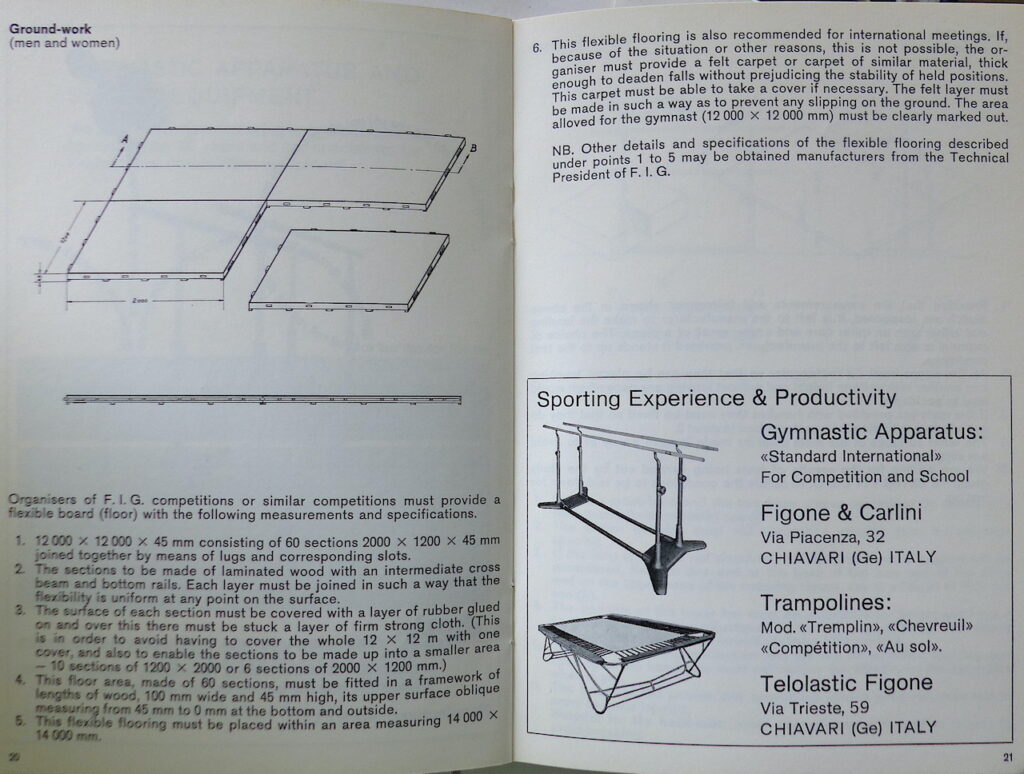

The Double Swing Floor

At the 1966 World Championships, the gymnasts competed on the double flex floor (sometimes called the “double swing floor” or the Reuther floor). It was essentially two floorboards sandwiched together with small wooden inserts between the layers. (Eventually, there would be foam blocks and rubber balls between the layers.) You could see it as a precursor to the modern spring floor. Though it was meant to flex in a way similar to the Reuther boards used on vault, it did not have as much “give.”

This type of floor appeared in the 1960 Apparatus Dimension booklet. However, it did not become mandatory for FIG events until the 1965 booklet.

According to Hardy Fink, similar ones were made with the collaboration of Spieth and Senoh for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and by Jansen-Fritsen for 1965 Europeans.

Video Footage

Here are a few routines from the apparatus finals that made their way to YouTube.

Floor Exercise

You can see that Gander’s words about risk, originality, and difficulty were heeded. Nakayama performed more difficulty than Endo and won the gold medal.

- First pass: Endo’s back full vs. Nakayama’s back 1.5

- Second pass: Endo’s handspring + front + headspring vs. Nakayama’s handspring + front + headspring + front + headspring

- Final pass: Endo’s pike open vs. Nakayama’s full

Still Rings

Voronin’s giants (5:27) were a big deal.

- Gymnasts had done giants before, but if you watch the 1964 Olympics, you’ll see that giants on rings were done with bent arms.

- Voronin did his giants with completely straight arms, setting the standard for giant swings for years to come.

High Bar

Nakayama (10:10) impressed gym nerds with his clean routine.

- Notice how clean his Tak/Adler, Endos, and Stalders are. They aren’t muscled.

- His Adler 1/1 to mixed grip + immediate bar vault looks very similar to a favorite combination of the men in recent quads: Adler 1/1 + Yamawaki

Some other skills performed at the 1966 Worlds (according to Wilhelm Weiler of Canada):

- Double full on floor

- Back full off p-bars

- Double back off p-bars

- Competed by Olli Laiho of Finland, according to Modern Gymnast, Aug/Sept, 1968

- Note: Rusty Mitchell of the USA performed a double back on floor at the 1964 Olympics

- Double-twisting flyaway off high bar

- Front 1.5-twisting flyaway off high bar

Generally speaking, gym nerds weren’t as impressed with the men as they were with the women. In Weiler’s words:

To sum up, it is felt that the women have come up with far more originality than the men.

Modern Gymnast, March 1967

Team Competition

Reminder: Teams consisted of 6 members. The best 5 scores on each event counted for both compulsories and optionals. While gymnasts were performing their compulsory and optional routines, they were competing for the team and all-around title, as well as vying for places in the event finals.

After compulsories, here were the standings.

| Country | Score | Final Ranking |

| 1. Japan | 287.85 | 1 |

| 2. Soviet Union | 285.90 | 2 |

| 3. East Germany | 278.80 | 3 |

| 4. Czechoslovakia | 275.80 | 4 |

| 5. Poland | 274.20 | 5 |

| 6. United States | 273.85 | 6 |

| 7. Italy | 273.45 | 9 |

| 8. West Germany | 273.20 | 8 |

| 9. France | 272.35 | 10 |

| 10. Yugoslavia | 271.40 | 7 |

| 11. Sweden | 270.60 | 12 |

| 12. Finland | 267.95 | 11 |

| 13. Hungary | 262.15 | 13 |

| 14. Norway | 258.10 | 14 |

| 15. Cuba | 256.85 | 15 |

| 16. Great Britain | 253.85 | 17 |

| 17. Spain | 252.35 | 16 |

| 18. Canada | 243.80 | 18 |

| 19. Austria | 242.55 | 19 |

| 20. Mexico | 221.20 | 21 |

| 21. New Zealand | 212.05 | 20 |

Compulsory Math

- Japan was ahead by almost two full points (1.95) after compulsories.

- The Japanese team had out-scored the Soviet team on floor (47.65 vs. 47.20), rings (48.10 vs. 47.75), vault (48.50 vs. 47.40), and high bar (48.45 vs. 48.15).

- Vault was the biggest point differential, with the Japanese team scoring 1.10 more than the Soviet team (48.50 vs. 47.40).

- The Soviets out-scored the Japanese only on parallel bars (48.20 vs. 47.95).

High Scores

The highest compulsory scores were awarded to Tsurumi and Kato on vault (9.80) and to Voronin on rings (9.80). (Though, according to Swiss newspaper L’Impartial, Voronin should have received a 9.90 for his compulsory rings.)

Lisistky injured; Shaklin in

Lisistky, who finished second at the Soviet trials for the World Championships, was injured, and Boris Shakhlin, then past his prime, took his place. The Dutch newspaper Het Vrije Volk said that Shakhlin “no longer had the strength to play a significant role.”

Het feit dat de Russen hun nationale kampioen Viktor Lissitski wegens een blessure thuis hebben moeten laten, is de homogeniteit van hun team natuurlijk niet ten goede gekomen. Zij moesten nu veteran Boris Shaklin (35)* opstellen, die weliswaar op de brug toonde nog steeds van grote klasse te zijn, maar toch niet meer de kracht bezit om een rol van betekenis te spelen.

Sept. 22, 1966

*Shakhlin was actually 34. The newspaper aged him.

After compulsories, the Italian newspaper L’Unità said that it was virtually impossible for the Soviet Team to catch the Japanese team:

È quasi impossible che l’URSS riesca a rimontare lo svantaggio nella serie degli esercizi liberi, ed é anzi probabile che lo scarto aumenti, siechè il Giappone dovrebbe ripetere il successo olimpico anche come proporzioni.

L’Unità, Sept. 22, 1966

The newspaper wasn’t wrong. Here are the final standings.

| Compulsories | Optionals | Total | |

| 1. Japan | 287.85 | 287.30 | 575.15 |

| 2. Soviet Union | 285.90 | 285.00 | 570.90 |

| 3. East Germany | 278.80 | 282.20 | 561.00 |

| 4. Czechoslovakia | 275.80 | 275.40 | 551.20 |

| 5. Poland | 274.20 | 276.40 | 550.60 |

| 6. United States | 273.85 | 276.55 | 550.40 |

| 7. Yugoslavia | 271.40 | 276.75 | 548.15 |

| 8. West Germany | 273.20 | 274.80 | 548.00 |

| 9. Italy | 273.45 | 272.55 | 546.00 |

| 10. France | 272.35 | 272.90 | 545.25 |

| 11. Finland | 267.95 | 273.75 | 541.70 |

| 12. Sweden | 270.60 | 270.50 | 541.10 |

| 13. Hungary | 262.15 | 268.10 | 530.25 |

| 14. Norway | 258.10 | 266.80 | 524.90 |

| 15. Cuba | 256.85 | 257.35 | 514.20 |

| 16. Spain | 252.35 | 259.30 | 511.65 |

| 17. Great Britain | 253.85 | 255.20 | 509.05 |

| 18. Canada | 243.80 | 254.95 | 498.75 |

| 19. Austria | 242.55 | 250.10 | 492.65 |

| 20. New Zealand | 212.05 | 217.10 | 429.15 |

On the Japanese Team

Dr. Joseph Goehler, VP of Deutscher Turner-Bund, believed that the Japanese team was the best ever. This was largely due to the team’s depth:

My greatest impression of the 1966 World Championships in Gymnastics was of the Japanese team, because no one gymnast could say he was better than the others and all were able to be a world champion. For example, Takashi Mitsukuri could start last in all events and would gather as many points as Nakayama or Tsurumi. Until now there has never been such a team as this Japanese one either in Olympic Games or World Championships.

Modern Gymnast, Nov. 1966

Body Type Myths

There was another belief about Japanese gymnasts circulating in Dortmund: The Japanese gymnasts had the right body type for gymnastics. (“Toont eens te meer de grote kracht van de Japanners, die voor het moderne turnen de ideale lichaamsbouw hebben.” Tubantia, October 24, 1966)

Soviets Take Risks

Meanwhile, the Soviet gymnasts relied on risk to try to catch the Japanese gymnasts. (“Toch hebben de Russen door het nemen van risico’s nog getracht het verschil zo klein mogelijk te houden.” Tubantia, October 24, 1966)

But the Soviets may have been overscored.

The Russians, handicapped by the absence of Lisitzky and Medvedev, could not resist the Japanese team. The two former Olympic champions Titov and Shakhlin could not obtain scores high enough to worry the Japanese, in spite of very advantageous scoring. But the new wave with Voronin, Diamidov, and Karasev portends a tight fight at the next Olympic Games. The technique of the Russians on six apparatus is perfect, especially on rings, pommels, and parallel bars, but they are clearly overtaken by the Japanese on floor and especially on vault. The Japanese take a lot more risks and accumulate “C” difficulties but sometimes make small mistakes. However, the code of points does not favor gymnasts.

Revue EP&S, Nov. 1966

Les Russes, handicapés par l’absence de Lisitzki et de Medvedev, n’ont pu résister à l’équipe japonaise. Les deux anciens champions olympiques Titov et Schaklin n’ont pu obtenir des notes suffisantes pour inquiéter les Japonais, malgré une cotation très avantageuse. Mais la nouvelle vague avec Voronine, Diamidov et Karassev laisse présager une lutte serrée aux prochains Jeux Olympiques. La technique des Russes aux six appareils est parfaite, surtout aux anneaux, aux arçons et aux barres parallèles, mais ils sont nettement dépassés par les Japonais au sol et surtout au saut de cheval. Les Japonais prennent beaucoup plus de risques et accumulent les difficultés « C » mais commettent parfois des petites fautes. Or, le code de pourcentage ne favorise pas les gymnastes.

Note

I don’t believe that Japanese gymnasts have the perfect body type for gymnastics or that there is a specific body type for gymnastics or that all Japanese people have the same body types. I’m including this detail because I think it’s important to recognize the myths that were being formed in the 1960s.

Notes on Team USA

Most of the news about Team USA was related to the training camp before the competition:

- The United States Olympic Committee authorized a four-week training camp at Penn State prior to the Championships

- There were lectures on “everything from marching, running, standing, and sitting postures to Germany today” (Modern Gymnast, Oct. 1966)

- My thought bubble: Can you imagine sitting through a lecture on marching?

- Films of the compulsory exercises were reviewed again and again

- The team had a dual meet with Norway just prior to Worlds

Notes on Team Canada

No Training Camp

Unlike the Canadian women, the Canadian men did not have a training camp prior to leaving for Dortmund.

Pommel Horse Problems

Canada started on pommels during compulsories

- Four gymnasts repeated their routines.

- Their best scores were a 6.85, 7.25, 7.50, 8.15, and 8.00 for a total of 37.75

- The problems continued during optionals.

- Albert Dippong, the team’s coach, said, “We really did very poorly, not only poorly but very bad” (Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1966, italics in the original)

High Bar Compulsory Woes

They had four falls on high bar during compulsories — everyone fell on the same movement: the stoop in and dislocate

Positive News

On the positive side, Wilhelm Weiler placed 10th on vault, which, at that time, was the highest place achieved by a Canadian male gymnast at the Worlds or Olympics.

Notes on Team Great Britain

Learning Experience

It’s important to remember that not every team attended the World Championships with the hopes of vying for medals. George Whitely, the British team’s manager, said:

Although we cannot compete with the Russians and the Japanese, we shall learn more than they will. Our main reason for coming is to learn.

Coventry Evening Telegraph, Sept. 22, 1966

Injuries Aplenty

Michael Booth was nursing a knee injury, and Brian Hayhurst had not recovered fully from a shoulder injury. But their injuries did not prevent the gymnasts from competing.

The All-Around Competition

Reminder: There wasn’t a separate all-around competition as there is today. At the same time that gymnasts were competing for the team title, they were competing for the all-around title. Their all-around totals were the sum of their optional and compulsory routines.

Here were the standings after compulsories:

| Gymnast | Country | Comp. Score | Final Ranking |

| 1. Voronin | URS | 57.90 | 1 |

| 2. Tsurumi | JPN | 57.75 | 2 |

| 3. Diomidov | URS | 57.60 | 11 |

| 4. Endo | JPN | 57.55 | 7 |

| 5. Matsuda | JPN | 57.25 | 10 |

| 6. Menichelli | ITA | 57.20 | 5 |

| 7. Cerar | YUG | 57.15 | 4 |

| 7. Kato | JPN | 57.15 | 6 |

| 9. Mitsukuri | JPN | 57.10 | 8 |

| 10. Nakayama | JPN | 57.00 | 3 |

| 11. Brehme | GDR | 56.75 | 9 |

| 11. Karasev | URS | 56.75 | 15 |

| 13. Kerdemilidi | URS | 56.45 | 12 |

| 14. Shakhlin | URS | 56.50 | 18 |

| 15. Titov | URS | 56.25 | 13 |

A Swiss Joke

After compulsories, the Swiss newspaper L’Express reported: “The best Swiss in contention was Fred Roethlisberger, who is competing for the team … of the United States.” (“Le meilleur Suisse en lice fut Fred Rothlisberger, qui s’aligne dans l’équipe… des Etats-Unis.” Sept. 22, 1966).

Volatile Optionals

The optional portion of the competition was volatile, causing several shifts in the rankings. Most notably, Nakayama jumped from 10th in compulsories to 3rd overall.

Final All-Around Standings – Top 20

Complete Results: 1-7

| FX | PH | SR | VT | PB | HB | Total | |

| 1. Voronin, Mikhail | URS | 116.15 | |||||

| C. | 9.60 | 9.55 | 9.80 | 9.50 | 9.75 | 9.70 | 57.90 |

| O. | 9.70 | 9.70 | 9.90 | 9.60 | 9.65 | 9.70 | 58.25 |

| 2. Tsurumi Shuji | JPN | 115.25 | |||||

| C. | 9.55 | 9.50 | 9.70 | 9.80 | 9.65 | 9.65 | 57.75 |

| O. | 9.60 | 9.50 | 9.60 | 9.50 | 9.60 | 9.70 | 57.50 |

| 3. Nakayama Akinori | JPN | 114.95 | |||||

| C. | 9.50 | 9.25 | 9.70 | 9.60 | 9.25 | 9.70 | 57.00 |

| O. | 9.80 | 9.50 | 9.80 | 9.50 | 9.50 | 9.85 | 57.95 |

| 4. Cerar, Miroslav | YUG | 114.75 | |||||

| C. | 9.45 | 9.65 | 9.40 | 9.30 | 9.60 | 9.75 | 57.15 |

| O. | 9.55 | 9.80 | 9.55 | 9.35 | 9.70 | 9.65 | 57.60 |

| 5. Menichelli, Franco | ITA | 114.65 | |||||

| C. | 9.60 | 9.35 | 9.70 | 9.30 | 9.65 | 9.60 | 57.20 |

| O. | 9.70 | 9.40 | 9.65 | 9.40 | 9.60 | 9.70 | 57.45 |

| 6. Kato Takeshi | JPN | 114.60 | |||||

| C. | 9.55 | 9.50 | 9.65 | 9.80 | 9.55 | 9.10 | 57.15 |

| O. | 9.60 | 9.55 | 9.65 | 9.55 | 9.50 | 9.60 | 57.45 |

| 7. Endo Yukio | JPN | 114.35 | |||||

| C. | 9.65 | 9.45 | 9.60 | 9.60 | 9.50 | 9.75 | 57.55 |

| O. | 9.70 | 8.95 | 9.35 | 9.55 | 9.40 | 9.85 | 56.80 |

*Modern Gymnast had some data entry issues for the individual event scores for places 8 and beyond.

Results: 8-20

| Gymnast | Country | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 8. Mitsukuri Takashi | JPN | 57.10 | 57.00 | 114.10 |

| 9. Brehme, Matthias | GDR | 56.75 | 57.30 | 114.05 |

| 10. Matsuda Haruhiro | JPN | 57.25 | 56.60 | 113.85 |

| 11. Diomidov, Sergei | URS | 57.60 | 55.65 | 113.25 |

| 12. Kerdemilidi, Valery | URS | 56.45 | 56.45 | 112.90 |

| 13. Titov, Yuri | URS | 56.25 | 56.50 | 112.75 |

| 14. Kubica, Mikołaj | POL | 55.00 | 57.60 | 112.60 |

| 15. Karasev, Valery | URS | 56.75 | 55.45 | 112.20 |

| 16. Sakamoto, Makoto | USA | 56.10 | 56.05 | 112.15 |

| 17. Kubica, Wilhelm | POL | 56.00 | 55.95 | 111.95 |

| 18. Shakhlin, Boris | URS | 56.40 | 55.45 | 111.85 |

| 19. Dietrich, Gerhard | GDR | 55.45 | 56.30 | 111.75 |

| 20. Storhaug, Åge | NOR | 54.85 | 56.40 | 111.25 |

The Japanese Gymnasts’ Performances

Kato’s Compulsory Struggles

Kato was leading compulsories until the final event. On high bar, he touched his hands on the ground during his dismount. What could have been a 9.90 routine became a 9.10 routine (L’Unità, Sept. 22, 1966).

“Due handicap gravi“

In the September 24 edition of L’Unità, the newspaper reported that Matsuda was injured and that Endo competed nervously (“l’assoluto nervosismo”).

(Note: Many newspapers reported that Endo competed nervously.)

Interestingly enough, Endo said this before the competition: “I fear no one. The biggest battle is against myself” (The Yomiuri, September 22, 1966).

Endo’s First Defeat

According to the Swiss newspaper L’Impartial (Sept. 24, 1966), this was Endo‘s first defeat in the all-around in five years.

Impressive Finishes

Despite the aforementioned challenges, the entire Japanese team finished in the top 10.

On Voronin

A Record Performance

At the time, Voronin’s 116.15 was the highest score ever achieved at the World Championships or Olympic Games.

Near Perfection

The Italian newspaper L’Unità stated that Voronin surprised the world with his absolute sureness and near perfection on every apparatus, which garnered him cheers from the public.

Voronin ha sorpreso per l’assoluta sicurezza e la quasi perfezione di ogni esercizio, che gli hanno vatso convinti applausi a scena aperta dal pubblico (dallo scarto pubblico va aggiunto: gli esercizi liberi del Giappone e dell’URSS e cioè la manifestazione più valida e più attraente di tutti i campionati Sono iniziati ad una ora impossibile, le otto del mattino!)

L’Unità, Sept. 24, 1966

Also, note that the Japanese and Soviet teams competed at 8 AM, which meant that there were few spectators.

The newspaper added

“Not only was the audience impressed; the judging panel gave Voronin an extremely rare 9.90 for his rings performance.” (“Non solo il pubblico e rimasto impressionato: la giuria ha dato un rarissime 9.90 a Voronin per la sua esibizione da gli anelli.”)

Athlete of the Year

Voronin was voted the Soviet Union’s Athlete of the Year in 1966 by the Soviet Federation of Sports Writers (New York Times, Dec. 28, 1966).

Odds and Ends

It’s hard to look at the scores and imagine what happened to some of the favorites. Here are some details about the optional exercises that the Dutch newspaper Tubantia reported on October 24, 1966.

During optionals, Diomidov fell off high bar during a giant sequence, taking him out of the running (8.35)

Logischerwijs vielen daardoor schläft offers. De grootste pechvogel was Sergei Diamidov, die aan het rek te veel waagde, bij een reuzenzwaai de controle verloor en voortijdig de grond raakte.

Endo hit his feet on the pommel horse. (8.95)

Op hetzelfde moment viel voor Endo op een ander podium bij het paard voltige ook het doek. De Japanner raakte met zijn voeten het paard en verspeelde daarmee zijn kansen op een van de medailles in het eindklassement.

Voronin was spectacular on pommel horse. His hands moved so quickly that it was almost impossible to follow. His work was reminiscent of Cerar’s. (9.70)

Even later bevestigde Voronin op hetzelfde toestel opnieuw zijn klasse. In oen razend tempo, waarin het verplaatsen van de handen bijna niet te volgen was, evenaarde de Rus bijna zijn presentatie van de Zuid Slavische meester op dit onderdeel, Miroslav Cerar, die bij de verplichte oefenstof 9.80 had gekregen een cijfer, dat de jury hem later op de dag bij de vrije uitvoering opnieuw toedacht.

Nakayama was stunning on floor. The laws of gravity didn’t apply to him as he effortlessly tumbled and transitioned between elements. (9.80)

Spectaculaire hoogtepunten in het turnen van de Japanners waren het rek en de vrije oefening. Akinori Nakayama reikte daarbij het hoogst. Bij de vrije oefening scheen voor de kleine Aziaat de wet van de zwaartekracht niet te gelden. In weergaloos tempo werkte hij een wervelende oefening af, waarbij gestrekte en schroefsalto’s onmiddellijk gevolgd werden door correcte zweefstanden.

Menichelli was disappointed after receiving a 9.70 on FX—much too low. As a result, he competed on vault without any inspiration, receiving a 9.40.

Menichelli die niet Cerar de Japans-Russische hegemonie, had kunnen doorbreken, trad na de vrije oefening die door de jury iets te laag werd gewaardeerd (9,70), duidelijk gedeprimeerd aan voor het paardvoltigeren. Zonder inspiratie draaide hij zijn oefening en toen daarna zijn waardering (9,40) bekend werd gemaakt, wist hij dat zijn kansen op het eremetaal waren verkeken. Hij werd vijfde achter Cerar, die zich ais vierde klasse verde.

As the European Champion, Menichelli had the best chance of breaking up the Japanese-Soviet “hegemony.”

Menichelli Still Impresses

Though Menichelli finished out of the medals, people were impressed that he was able to finish fourth, beating both Kato and Endo, the reigning Olympic champion (L’Impartial, Sept. 24, 1966).

High Scores

On the men’s side, only two men received 9.90s at the 1966 World Championships:

- Nakayama received a 9.90 in the high bar final.

- Voronin received two 9.90s: both on rings, one during the optional competition and one during event finals.

Event Finals

Reminder: Only six gymnasts qualified for event finals. Qualification for finals was based on the compulsory *and* optional scores on each event.

Your total score was the average of your compulsory and optional scores (labeled “COA” in the tables below) plus the score for your routine during event finals.

Floor Exercise

| Country | COA | Finals | Total | |

| 1. Nakayama Akinori | JPN | 9.650 | 9.75 | 19.400 |

| 2. Endo Yukio | JPN | 9.675 | 9.70 | 19.375 |

| 3. Menichelli, Franco | ITA | 9.650 | 9.65 | 19.300 |

| 4. Kato Takeshi | JPN | 9.575 | 9.65 | 19.225 |

| 5. Karasev, Valery | URS | 9.550 | 9.45 | 19.000 |

| 6. Tsurumi Shuji | JPN | 9.575 | 9.30 | 18.875 |

Side/Pommel Horse

| Country | COA | Finals | Total | |

| 1. Cerar, Miroslav | YUG | 9.725 | 9.80 | 19.525 |

| 2. Voronin, Mikhail | URS | 9.625 | 9.70 | 19.325 |

| 3. Kato Takeshi | JPN | 9.525 | 9.60 | 19.125 |

| 4. Brehme, Matthias | GDR | 9.525 | 9.50 | 19.025 |

| 5. Tsurumi Shuji | JPN | 9.500 | 9.50 | 19.000 |

| 6. Laiho, Olli | FIN | 9.550 | 9.25 | 18.800 |

Still Rings

| Country | COA | Finals | Total | |

| 1. Voronin, Mikhail | URS | 9.850 | 9.90 | 19.750 |

| 2. Nakayama Akinori | JPN | 9.750 | 9.75 | 19.500 |

| 3. Menichelli, Franco | ITA | 9.675 | 9.80 | 19.475 |

| 4. Kato Takeshi | JPN | 9.650 | 9.65 | 19.300 |

| 5. Diomidov, Sergei | URS | 9.650 | 9.55 | 19.200 |

| 6. Tsurumi Shuji | JPN | 9.650 | 3.00 | 12.650 |

Voronin‘s 19.750 was the highest total during event finals. 🎉

Vault/Long Horse

| Country | COA | Finals | Total | |

| 1. Matsuda Haruhiro | JPN | 9.750 | 9.675 | 19.425 |

| 2. Kato Takeshi | JPN | 9.675 | 9.650 | 19.325 |

| 3. Nakayama Akinori | JPN | 9.550 | 9.500 | 19.050 |

| 4. Endo Yukio | JPN | 9.575 | 9.125 | 18.700 |

| 5. Voronin, Mikhail | URS | 9.550 | 9.100 | 18.650 |

Reminder: This was the first time the male gymnasts had to do two different vaults in finals.

Parallel Bars

| Country | COA | Finals | Total | |

| 1. Diomidov, Sergei | URS | 9.800 | 9.75 | 19.550 |

| 2. Voronin, Mikhail | URS | 9.700 | 9.70 | 19.400 |

| 3. Cerar, Miroslav | YUG | 9.650 | 9.70 | 19.350 |

| 4. Menichelli, Franco | ITA | 9.625 | 9.60 | 19.225 |

| 5. Brehme, Matthias | GDR | 9.600 | 9.60 | 19.200 |

Horizontal Bar

| Country | COA | Finals | Total | |

| 1. Nakayama Akinori | JPN | 9.775 | 9.90 | 19.675 |

| 2. Endo Yukio | JPN | 9.800 | 9.80 | 19.600 |

| 3. Mitsukuri Takashi | JPN | 9.725 | 9.70 | 19.425 |

| 4. Cerar, Miroslav | YUG | 9.700 | 9.70 | 19.400 |

| 4. Voronin, Mikhail | URS | 9.700 | 9.70 | 19.400 |

Small Note

Menichelli stepped out of bounds on floor, costing him the gold medal.

Another Small Note

Both Voronin and Endo put their hands in the “forbidden zone” on vault. (Reminder: The vault had zones for men.)

Voronin, die zich als enige tussen het Japanse geweld op de paardsprong had weten te werken, zag zijn kansen verloren gaan, omdat hij even als Endo zijn handen in de verboden zone plaatste, hetgeen hem op een reglementaire aftrek van een volledig punt kwam te staan.

Algemeen Dagblad, Sept. 26, 1966

On the topic of vault: It was rather boring.

It is regrettable that the code of points has not evolved and that it does not force gymnasts to present new vaults. This test seemed monotonous because only two vaults were generally chosen: the so-called “Yamashita” vault and the “piked handspring on the neck”. Few twisting hecht vaults, or “Yamashita with 1/2 or full twist, no Super-Yamashita.” It’s a shame for the technical evolution of this apparatus.

EP&S, Nov. 1966

Il est regrettable que le code de pointage n’ait pas évolué et qu’il ne force pas les gymnastes à présenter de nouveaux sauts. Cette épreuve a semblé monotone car deux sauts seulement furent généralement choisis : le saut dit de « Yamashita » et la « lune carpée sur le cou ». Peu de saut de brochet avec vrille, ou de « Yamashita avec 1/2 ou vrille complète, pas de Super-Yamashita ». C’est dommage pour l’évolution technique de cet agrès.

Bigger Note with Decades-Long Implications

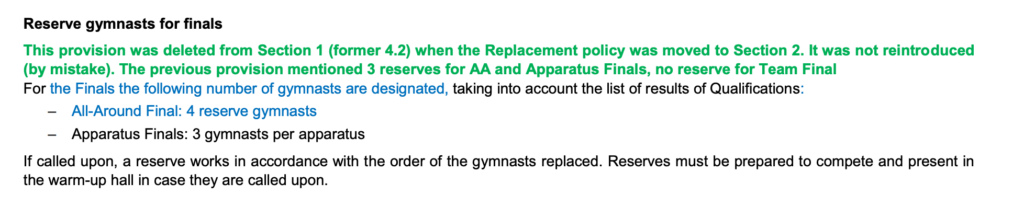

Tsurumi Shuji qualified for all six event finals. However, he was injured during the rings competition, and there weren’t any reserve gymnasts to take his place in the remaining finals.

That’s why there are only five scores on vault, parallel bars, and high bar in the tables above.

This resulted in the FIG making a rule change about reserves for event finals:

The six best gymnasts in each event shall be qualified for the finals and the next two gymnasts’ names shall be shown in the list of the finals as alternates. These two gymnasts shall be ready (in gymnastic clothes) during all of the finals and be ready to replace one or more gymnasts who are injured and unable to continue the competition. If these two gymnasts do not act according to the rules, they shall be penalized as per Art. 34 of the Technical Regulations

Modern Gymnast, Aug. 1967

This rule should sound familiar to modern gym nerds — except the FIG Technical Regulations nowadays call for three gymnasts instead of two.

Finally, Voronin performed his “Voronin” release on high bar. (Though, Lisitsky may have performed it one year earlier, at the 1965 European Championships.)

It is the apparatus that evolves the fastest and the Japanese are the great masters there; they present in their exercise up to six or seven “C” difficulties. Again, the “code of points” did not follow, and that’s a shame.

Voronin perfectly achieves the crossing of the bar from the big front turn [i.e. a Voronin] created by Lisitsky in Antwerp at the European Championships.

EP&S, Nov. 1966

C’est l’agrès qui évolue le plus vite et les Japonais y sont les grands maîtres ; ils présentent dans leur exercice jusqu’à six ou sept difficultés « C ». Là encore, le « code de pointage » n’a pas suivi et c’est bien dommage.

Voronine réalise à la perfection le franchissement de barre depuis le grand tour avant créé par Lisitsky à Anvers à la Coupe d’Europe.

Overshadowed

Truth be told, the women’s competition overshadowed the men’s. The two major headlines coming out of Dortmund were:

- The capitvating performances of the Soviet Union’s teenage gymnasts

- Doris Brause’s uneven bars routine

All that and more in the next series of posts.