What was it like training in Japan in the late 1960s? How many hours did they train? How was the Japanese gymnastics system set up? Did they use spotting belts?

Let’s take a look…

Men’s Gymnastics | Women’s Gymnastics | Bookends: Additional Articles

Note: The year in the title of this post is arbitrary. This blog post will jump from year to year in the late 1960s.

Men’s Gymnastics in Japan

When it comes to men’s artistic gymnastics, there is an abundance of articles on the Japanese men’s gymnastics system. You see, the American and Japanese systems shared some similarities. Both countries had thriving gymnastics programs at their local high schools and universities in the late 1960s. Those programs served as talent funnels for both countries’ Olympic teams.

The difference: The Japanese gymnasts were far more successful than the U.S. gymnasts, and the American gym community wanted to understand why.

Below, you’ll find excerpts from a few articles from the late 1960s.

1967: Koguchi Ryoji, Endo Yukio, and Hayata Takuji

On their way back to Japan, after the Little Olympics in 1967, the Japanese team stopped in Long Beach, California for an exhibition. At that time, the editors of Modern Gymnast interviewed Koguchi Ryoji, the general manager for the Japanese teams, as well as gymnasts Endo Yukio and Hayata Takuji.

Here are a few excerpts from their interviews.

MG stands for Modern Gymnast.

On All-Arounders vs. Event Specialists

MG: Does everyone work all-around?

Mr. Koguchi: Yes, there are only a few specialists. They may compete in tumbling or trampoline in the high schools or universities.

Note: In the United States, there was a debate about event specialists. Many gymnastics coaches were against specialization and pushing for more all-arounders at all levels of men’s gymnastics so that the United States could be more competitive internationally.

On the Structure at the High School and University Levels

MG: What is the length of competition in the high schools and universities? The period of the dual meet season?

Mr. Koguchi: A college dual meet, both optional and compulsory routines, will take two days. Whether both optional and compulsory routines are used depends on the league. There are three divisions in the university-level competition. To determine the championship team takes a full week. With respect to the high schools, on the national level, there are 48 prefectures (roughly equivalent to states). Only one high school team represents a prefecture at the national competition. The gymnastic season runs from May to December.

MG: How many university teams are there?

Mr. Koguchi: Close to 200 teams.

The Framework of Their Workouts

MG: How do you handle practice sessions?

Mr. Koguchi: We first start off with warm-up sessions of calisthenics. Each gymnast stretches and loosens every part of his body. Then this is followed by group tumbling — handsprings, cartwheels, neck kips, etc. Then the group circulates to each event and warms up, as a group, on that apparatus.

Government Subsidies for Athletes

MG: What is the extent of government support for gymnastics in Japan?

Mr. Koguchi: When a gymnast reaches the national level of competition, there is a government subsidy for such things as transportation, workout clothes, equipment, etc. In December, 36 gymnasts will be selected for next year’s Olympic team trials. In May, another competition will be held and half of these will qualify. During this time of training, the government will provide room and board. In July, the final trials will be held to select the six team members and one alternate who will compete in Mexico City.

Staying on Top

MG: What are you doing to remain on top in the Olympics?

Mr. Koguchi: We are doing a lot of research. We have a magazine (Gymnastics Research) sponsored by the Japan Federation devoted to research. The editor is Mr. Nakajima. The magazine attempts to compare such great athletes as Caslavska, Voronine. For example, Caslavska may be shown doing a vault and a Japanese. The analysis tells why Caslavska is doing it better. This way we learn. We also use movies.

MG: Have you made use of the video recorder?

Mr. Koguchi: Yes, for ten days before we left for Mexico City, we used it to study our exercises.

Note: Video replay was a big topic in the late 1960s. Modern Gymnast had several articles on the topic.

On Strength Training

MG: What sort of strength-building exercises do you use in developing young gymnasts?

Endo: A distinction must be made between simply building muscles and developing the muscles needed to do a move. Aside from arduous workouts six times a week, there is no regular weightlifting program to build muscles. They go through a warm-up, then light routines, and then heavier routines. It is this practice which builds up and develops muscles. Weightlifting is not a way of building a gymnast’s body in Japan.

On Learning New Skills and Spotting Belts

MG: How do you learn and practice hazardous moves?

Hayata: The gymnasts work as a team, studying the moves of one another so they can learn how to do the moves better.

MG: Are spotting belts used?

Hayata: No. At the elementary (lower echelon) level, a spotting belt may be used, but at the high caliber levels, no spotting belts are used. Thick sponge rubber mats are used for landings to prevent injuries.

On Year-Round Training

MG: Do you stay in shape all year round?

Endo: The Japanese in the higher echelons work throughout the year. This is why they feel they are able to stay on top. During the off-season, they work out to stay in shape, but also for developing new moves. In the event of slight injuries to some portions of the body, by running and other exercises.

On the Length of Training Sessions

MG: How many hours of workout do you put in a day?

Endo: Two and a half hours until the national level of competition is reached, then four hours a day. This goes for three days, rest one day, and so on.

On Improving Weak Events

MG: How do you strengthen a gymnast’s weak event?

Endo: The training period for that event is lengthened in order to strengthen it.

On Routine Construction

MG: What goes into the planning or a routine?

Endo: One must know the different A, B, C, moves in order to plan it. At the beginning level, the coach’s advice is sought. After a routine is developed, the coach assists the gymnast and may make adjustments by dropping or changing parts.

On Tapering before Meets

MG: What is your preparation for a meet?

Endo: Whether for a meet or an exhibition, I require a period of relaxation. In preparation for a big meet, I work out very hard up to a week before but taper down as the meet approaches until the day before when I only work out lightly. On the day of the meet itself I have plenty of energy and stamina and can really put out. In big meets in Japan when all six events are going at once, the gymnast will generally know ahead of time what events he will work first. He plans his workouts accordingly.

Note: The next section will dive deeper into how the Japanese gymnastics teams structured their training leading up to a meet.

Only the weaker gymnasts come to the United States to study.

MG: A number of young Japanese gymnasts have come to the US for college—Ito, Kanzaki, Hayasaki—are there likely to be more? What would be their purpose since gymnastics is at such a high level at home?

Hayata: Members of the National teams will not leave Japan because they cannot learn more gymnastics outside of Japan. The lower echelon gymnasts may come because they wish to receive a Master’s degree or some other educational instruction.

On Smoking and Drinking

MG: What about smoking and drinking?

Endo: The Japanese, like others, have their bad habits, and admit that smoking and drinking are such. But they are still on top and top gymnasts feel that their hard training more than overcomes ill effects. (Endo admitted that when his throat hurts, he quits smoking.) Training as hard as they do, they reach a point of utter exhaustion after a workout. Then a little alcohol or glass of beer relaxes them and relieves tension so they can sleep better. In summary, it is not the bad habits so much as the good ones which affect the end result.

—

Quotes are taken from Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1967

1969: Makoto Sakamoto

Makoto Sakamoto was one of the top U.S. gymnasts in the 1960s. He had the highest all-around finish (20th) for an American at the 1964 Olympics.

Born in Japan, he returned to his homeland to train for a year. He wrote an article about how Japanese gymnasts prepare during the five weeks leading up to a competition.

His article gives more context to what Endo and Hayata said above.

Week 1: Gasshuku + Strenuous training

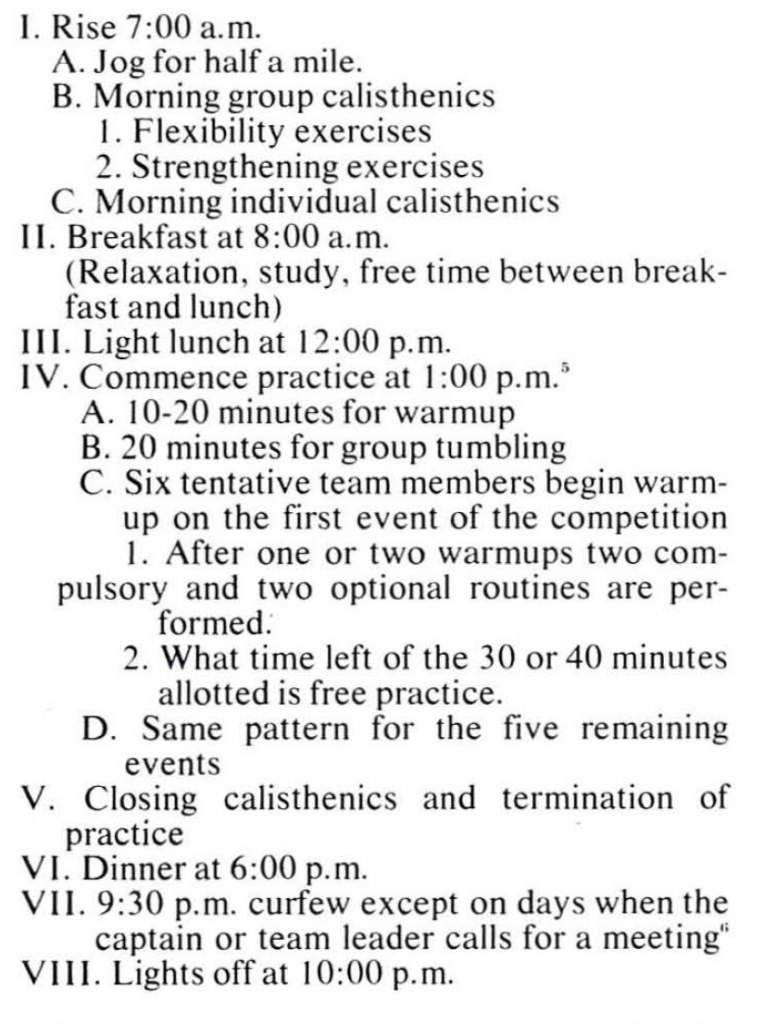

On the first week the nine competitors and the team leader live together in a dormitory and participate in what the Japanese call “gasshuku.” The training is the most strenuous during this week due in part to the numerous amount of routines and to the lack of experience in going through them. If the gasshuku lasts for seven days, all the days are about the same except the fourth day when it is used for recuperation. Below is an outline of a typical day from the first and last three days of the training camp:

On the recuperation day

On the fourth day we start the day with the same morning schedule, but in the afternoon we practice freely for only about two hours.

Week 2: A Lighter Load

The workload for the second week is less than that for the first week, but we must still complete at least one compulsory and one optional routines. Unlike gasshuku, we do not live together, and although the team leader recommends everyone to do his morning calisthenics, most of the gymnasts fail to do them. As in the first week, the fourth day is reserved for light practice, but depending upon our condition, the team leader or captain may force us to continue the high pace for as long as ten days. On weeks when we have no recuperation day, the last half of the week is terribly difficult. In retrospect, I was able to endure the rough training only by trying to compete with the other gymnasts who worked so tenaciously.

Week 3 + 4: Back to the Strenuous Training of Week 1

The third and fourth weeks are similar to the first, but again the gymnasts do not live in the dormitory.

Week 5: Gasshuku + Light Training + Diluted Whiskey

On the fifth week, we enter gasshuku for the second time, but because it is the week of the competition, the practice schedule is light. Two days before the meet we must go through at least one full compulsory and one optional routine on all six events. The day before the meet is called “choseibi” (adjustment day), and the gymnast is free to do anything he wants after doing the morning group calisthenics. Usually in the evening of the choseibi (also the day before the meet), diluted whiskey and snacks are served by the team leader to ease the minds of the gymnasts, and the lights go off around 11:00 p.m. instead of 10:00 p.m.

On Practice Meets + Judges’ Notes

Before closing this short article, I must mention something about the “shigikai” (practice meet). These meets are held at least two times during the five weeks under identical conditions as in the actual competition. Under actual competition condition means bowing to the superior judge, taking three minutes for warmup and no repeating of routines. After completing the routines the judges comment individually on his weak spots, and it was in their technically detailed and artistically fine criticisms that I found most fruitful during my one-year visit to Japan.

On spending time together talking only about gymnastics

The Japanese gymnasts form a huddle before and after practice during which time no one is allowed to eat, smoke or talk except about gymnastics.

On training through injuries — no exceptions

Unless an injury is severe the gymnast follows the schedule to the letter. Our captain with a swollen left wrist the size of a lime worked indefatigably every day, bearing pain which I doubt I could have endured.

All quotes are from Modern Gymnast, November 1969

Additional Note

The Japanese gymnasts were good at basics. Steve Hug also spent a year in Japan training, and this is what Modern Gymnast wrote when he returned:

Yes, Steve Hug is in the lead with 53.5 points, but everyone agrees his extra points owe in part to his work on basics in Japan – his swing and timing are especially improved.

Modern Gymnast, June/July 1970

Women’s Gymnastics in Japan

During this time period, Modern Gymnast didn’t dedicate much ink to women’s gymnastics — much less Japanese women’s gymnastics. But I was able to find a few articles from the Yomiuri, an English-language newspaper out of Japan.

Warning: This section will talk about belittling gymnasts, gymnasts’ eating habits, and drunkenness.

1966: Coach Takahashi Kazuo

In 1966, Japanese TV aired a series on heroes of modern times. One episode was dedicated to Takahashi Kazuo, a top women’s gymnastics coach at the time.

He drank a lot, and his “hard training” techniques were thought to produce champions.

Here’s the television program description from The Yomiuri, September 22, 1966:

“Heroes of Modern Times”

CHANNEL 6—10.30-11 pm

The “hero” in this week’s installment is Kazuo Takahashi, 42, a teacher of physical training at the Yamagata prefectural Yonezawa Commercial High School.

A bearded man who always wears a judo uniform, he often reeks of alcohol after his nightly drinking sprees.

However, he is Japan’s top gymnastics coach for women.

His team has won gymnastics contests in the National Athletes Meet for three consecutive years, and is expected to walk away with this year’s National Athletic Meet, which opens next month in Beppu, Kyushu.

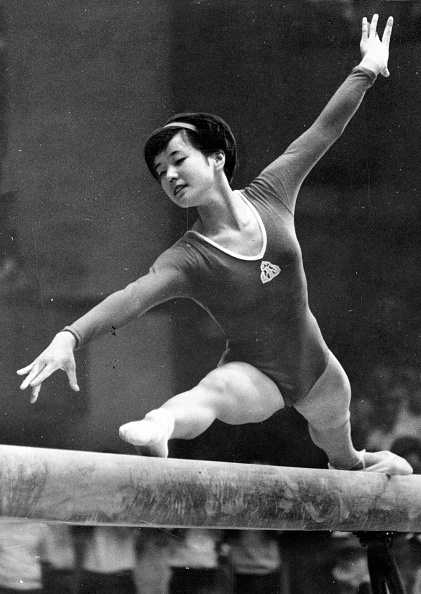

The program shows Takahashi’s profile, with the camera focusing on his “hard training” which produced Sachiko Tajima, 18, and other hopeful gymnasts.

It’s unclear what was meant by “hard training,” but the next section might give us an idea…

1968: Coaches Oshima Shigeo and Yukiko

In 1968, The Yomiuri published an article about Hanyu Kazue, the 17-year-old who made the 1968 Japanese team.

She was the first high school student selected for a gymnastics team in Japan, and she ended up finishing 13th in the all-around in Mexico City, which was Japan’s highest WAG all-around finish in 1968.

The article, however, was more about her high school gymnastics coaches, Oshima Shigeo and Yukiko.

Couple Trains Girl Gymnast for Olympics

“You fool! How many bowls of rice did you have this morning? No! No! No! That’s not correct! Your movements are wrong, you fool! You’re off balance! You’ve lost your precision!”

Those words are sharply spoken—never shouted—by Shigeo Oshima, the 26-year-old gymnastics coach of the prefectural senior high school at Takefu, Fukui-ken.

“Let’s try it again,” he continues. “And remember your turns and rhythm.”

Standing beside him in the gymnasium is his wife, Yukiko, 26, who is manager and also a gymnastics instructor. She, too, has a sharp tongue as biting as her husband’s. But, she, too, never shouts or yells at their five-member high school girls’ gymnastics squad.

In less than two years, the husband-and-wife instructors with their Spartan-like training methods, have brought Takefu high school, their alma mater, its first championship in gymnastics at the inter-high and national athletic meets. Both were considered average gymnasts in their youth and Takefu didn’t even have a mediocre class until the Oshimas took over.

Of major importance is that they were responsible for the upbringing and training of a 17-year old high co-ed who earned a berth on the seven-member Japanese women’s Olympic gymnastics squad. The young hopeful is Kazue Hanyu, the first high school student selected for the gymnastics team in Japan.

Shigeo and Yukiko were classmates in Takefu high school. They were also members of the school’s gymnastics club, there being no class in gymnastics. Both competed in national athletic meets. Shigeo was told to give up the sport, that he didn’t have the ability and that he would never make it. That fired him to try harder than ever. He not only surpassed the others but was named team captain. But that was the furthest he got. After graduation he helped his family run a meat shop, then was hired in the physical education section of the Fukui city hall.

Yukiko went on to Tokyo Women’s College of Physical Education. She had to give up active training, having suffered injuries from a fall. She taught in middle school before she was assigned to physical education at her alma mater.

In 1966 Yukiko was named manager of the high school gymnastics team, the school having decided to place emphasis on the sport, and Shigeo coach, on a part-time basis with the approval of city hall officials. The Oshimas saw eye-to-eye, decided to work as a team, so they were married that year.

During the morning hours, Yukiko taught physical education, in the afternoon gymnastics. Shigeo worked at his city hall desk until 12 noon, then joined his wife at high school for gymnastics.

Shigeo says it was tough at the beginning. He went out and collected everything possible on gymnastics published outside of Japan. He spent hours trying to translate and understand what it was all about. He and his wife stayed up late at night working out sketches and forms for the girls.

“To instill a spirit of competitiveness among ourselves,” Shigeo says, “I took over the parallel bars and long horse while Yukiko was responsible for the balance beam and floor exercises. Then we had the girls fight for the highest points to make them aware of the importance of giving their best performance at all times.”

The Spartan-like training, at times, is tough and girls muff their twists and turns. The Oshimas are merciless during training. Their harsh remarks sting, bite, lash and whip. The girls break out in tears. They stifle their sobs and try again and keep repeating until they are told at the finish: “Smile, have you forgot to smile” or “You have some sand in your eyes.” The girls manage to break out with a weak smile.

“On several occasions,” says Shigeo Oshima, “we’ve wanted to toss in the towel and call it quits. It’s a heartless task and I imagine the girls feel we’re demons. But they’re of the age when they hurt easily but recover much faster. They’re very dear to us, one of our very own.”

Yukiko says, “They’ve been times when I forgot my responsibilities as a housewife and mother. From now on I’ll have to devote more time to our 1-year-old baby girl, Yayuko.”

The Oshimas had planned on joining the women’s gymnastics team at the Mexico Olympic Games to be with their protegee, Kazue Hanyu. They gave up the idea when it was decided to cut down on the size of the delegation and individual coaches. After watching Kazue, dubbed “Nyu,” undergo her paces in line with the Olympic gymnastics trainers, the Oshimas are confident that she’ll adapt herself and put up a grand performance at the Mexico games.

The Yomiuri, August 25, 1968

The Gist

The Oshimas knew that they were demons. (“I imagine the girls feel we’re demons.”)

Nevertheless, they still chose to use belittlement as a motivational strategy. (“Their harsh remarks sting, bite, lash and whip. The girls break out in tears.“)

What’s more, the Oshimas believed that teenage gymnasts could handle this type of treatment because they would get over it easily. (“They’re of the age when they hurt easily but recover much faster.”)

So, why do the Oshimas do it?

The article suggests that this type of treatment brought success:

In less than two years, the husband-and-wife instructors with their Spartan-like training methods, have brought Takefu high school, their alma mater, its first championship in gymnastics at the inter-high and national athletic meets.

We saw this attitude in the previous article, as well — the belief that demeaning gymnasts brings success.

A Note on Gender Dynamics

The gender dynamics of the event selection are fascinating. Yukiko, the wife, was responsible for beam and floor (presumably because choreography and dance were seen as women’s work), while Shigeo, the husband, was responsible for vault and bars.

A decade later, in Romania, the Károlyis and Géza Poszár had a slightly different gender dynamic:

– How equal are the members of the coaching team?

– My husband is the head coach, he coordinates the workout. Géza does the artistic execution, and the three of us work out the floor exercises together. My favorite event is the beam[…] As for acrobatics, vaulting, and bars, the main role belongs to my husband.

— Mennyire egyenrangúak az edzői csport tagjai?

— A férjem a főedző, ő hangolja össze a munkát. Géza a művészi kivitelezést végzi, és hárman együtt dolgozzuk ki a talajgyakorlatokat. Az én kedvenc szerem a gerenda[…] Az akrobatikánál, az ugrásnál és a korlátgyakorlatoknál a főszerep a férjemé.

Dolgozó Nő, 36, July 1980

Note: This is not an endorsement.

While the article suggests that the coaching-as-belittlement technique made the couple’s high school successful, I do not endorse this style of coaching.

I have reprinted both articles as cultural artifacts, and I believe that it’s important to understand how the coach-athlete relationship was being presented at the time in the Japanese media.

Note: These aren’t cherry-picked articles.

These are the only two articles I found in the Yomiuri about WAG training and coaching from the time period. It is hard to tell if this type of coaching was pervasive, but it’s important to note that the media chose to highlight these specific coaches and their training styles for English-speaking audiences.

Bookends: Additional Articles

In this section, I’ll look at a few articles about Japanese gymnastics that I found fascinating but can’t fit neatly into other blog posts. I’m calling them bookends because their dates (more or less) precede or follow the years discussed above.

1958: Insurance

Who doesn’t like to talk about insurance? Here’s an article about Japanese sports insurance.

Sports Group Insurance

Sports group liability insurance will go into effect from today by which athletes can be insured against injury and death.

However, the insurance will be limited to amateurs competing in groups of 50 or more athletes.

Sports are classified into three categories A, B, and C and premiums will be paid according to the sport involved.

A covers wrestling, boxing, sumo, karate, gliding, and American football. B includes mountain climbing, skiing, hockey, equestrian events, rugby, soccer, baseball, judo, cycling. C embraces kendo, fencing, skating, table tennis, lawn tennis, swimming, handball, shooting, volleyball, basketball, boating, yachting, track and field, weight lifting, badminton, golf, softball, archery, and gymnastics.

The maximum coverage is ¥500,000 per group.

Yomiuri Japan News, April 1, 1958

In 1958, ¥500,000 was roughly equal to $1,400 USD.

1966: A Ban on Driving for Japanese Gymnasts

The Japan Gymnastics Federation has banned all first-rate gymnasts from driving motorcars with a threat of suspension for any violations.

The federation took this action following an auto accident by one of its members hwo knocked down a bicycle rider.

The Yomiuri, May 7, 1966

Note: I’m not sure how long this ban was in effect or how well it was enforced. In 1973, Kato Sawao was involved in a hit-and-run accident in Niigata. He confessed to the police. (The Daily Yomiuri, Jan. 22, 1973).

1974: A Report on Deaths from Gymnastics

In 1974, the Japanese Gymnastics Association assembled a report on gymnasts who either died or were disabled while training in Japan.

Here’s the news write-up about the report.

Gymnasts Jump to Death

An interim report of a survey on accidents among university students while practicing gymnastics, which was revealed Saturday by the Japan Gymnastics Association (JGA), revealed that 10 students died attempting difficult gymnastics performances during the two-year period from 1972 to January 1974.

Another 13 students have become disabled as a result of injuries suffered from various difficult performances during the same period, the JGA officials said.

Much encouraged by the outstanding results of Japanese gymnastic athletes in international events, including Olympic Games, of late, many students, in their physical education classes, tend to practice difficult and complicated feats, which are termed in Japanese “ultra C.”

The JGA recently conducted a survey on the number of accidents involving students while practicing gymnastics by issuing questionnaires to local JGA chapters and 120 universities throughout the country.

The interim report, which was revealed Saturday, was compiled from reports by 24 local JGA chapters and 21 universities.

According to the report, five students died and two others became disabled while practicing floor exercises, one died and another two became disabled while practicing on the rings, three died and one other became disabled while practicing horse vaulting and one died and another eight became disabled while practicing horizontal bar.

The number of casualties would further increase when all the reports reached the JGA from the remaining local JGA chapters and universities, the officials added.

The Daily Yomiuri, February 25, 1974

Mukhina’s paralysis raised awareness of the dangers of the sport, but there are many others whose names have been forgotten.