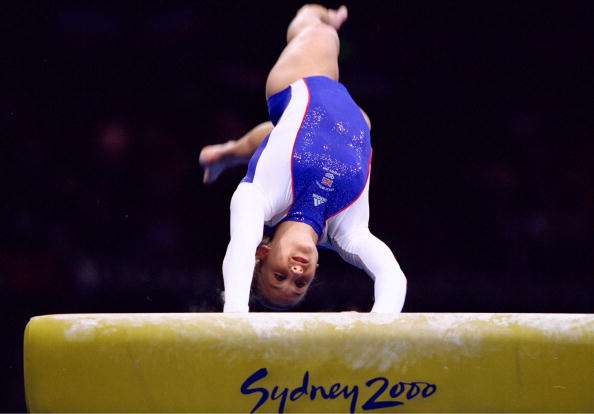

During the women’s all-around at the Sydney Olympics, the vault was set 5 cm too low. Multiple gymnasts vaulted on a horse set at 120 cm when it should have been set at 125 cm. As a result, several gymnasts fell, including the favorite for the all-around title, Svetlana Khorkina.

During the third rotation’s warmup, Allana Slater insisted that something was wrong, and eventually, the vault was raised to the correct height (125 cm). After the competition, Kym Dowdell, the competition manager, issued a statement:

“Unfortunately, equipment personnel failed to set the vault at the appropriate height.”

Qtd in. International Gymnast, November 2000

But how? How do equipment personnel fail to set the vault correctly?

That’s the question that the gymnastics community has been asking for over two decades.

Well, I have a hypothesis. It has to do with the apparatus norms that were printed in 2000.

Note: Reeder was injured on her vault landing during the all-around final.

The 1998 Height Increase

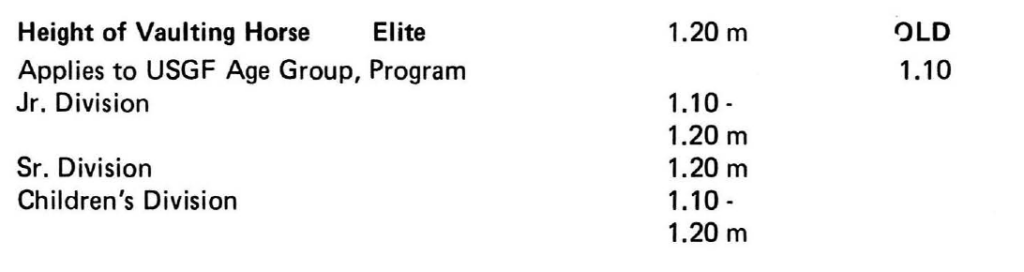

From 1950 until the mid-1970s, the women’s vault was set at 1.10 m from the ground. Then, in the mid-1970s, the vault height increased from 110 cm to 120 cm. In a technical bulletin for the United States Gymnastics Federation (USGF) in 1976, Jackie Fie noted some of the changes for 1975-1979. One of those was the vault height:

Those 10 centimeters helped usher in a new era of vaults in women’s gymnastics, including Nellie Kim’s full-twisting Tsukahara. Some of the most iconic vault moments in the history of women’s gymnastics happened at this height. Natalia Yurchenko, for example, performed her namesake on a horse set at 120 cm, and when Kerri Strug vaulted during the Team Finals in 1996, the horse was also set at 120 cm.

For over 20 years, from the mid-1970s to the late-1990s, the height of the vault didn’t change. Then, the Women’s Technical Committee of the FIG increased the vault height to 125 cm from the floor. This change was effective January 1, 1998.

Here’s what Technique, a publication of USA Gymnastics wrote:

Since the FIG will be raising the horse height 5 cm as of January 1, 1998, the committee discussed allowing the Jr. Olympic athletes the option to use the 125 cm horse height for the 1997-98 season.

Technique, November/December 1997

By the time the women’s all-around competition happened on September 21, 2000, the new vault height had been in place for almost 1,000 days.

But for whatever reason, that change didn’t make it into the Apparatus Norms, which were published in 2000.

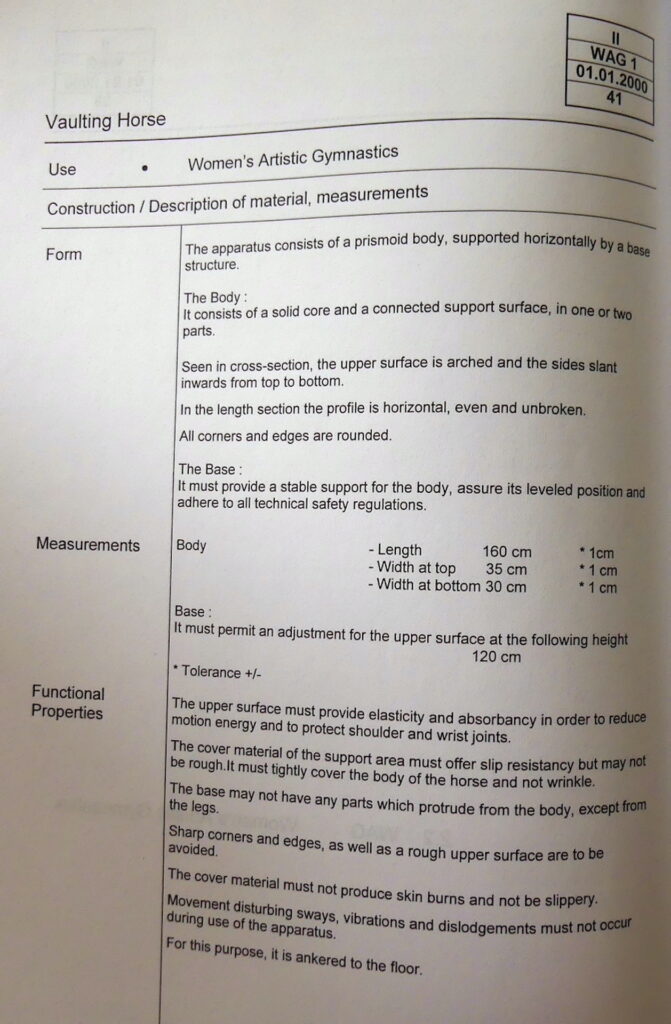

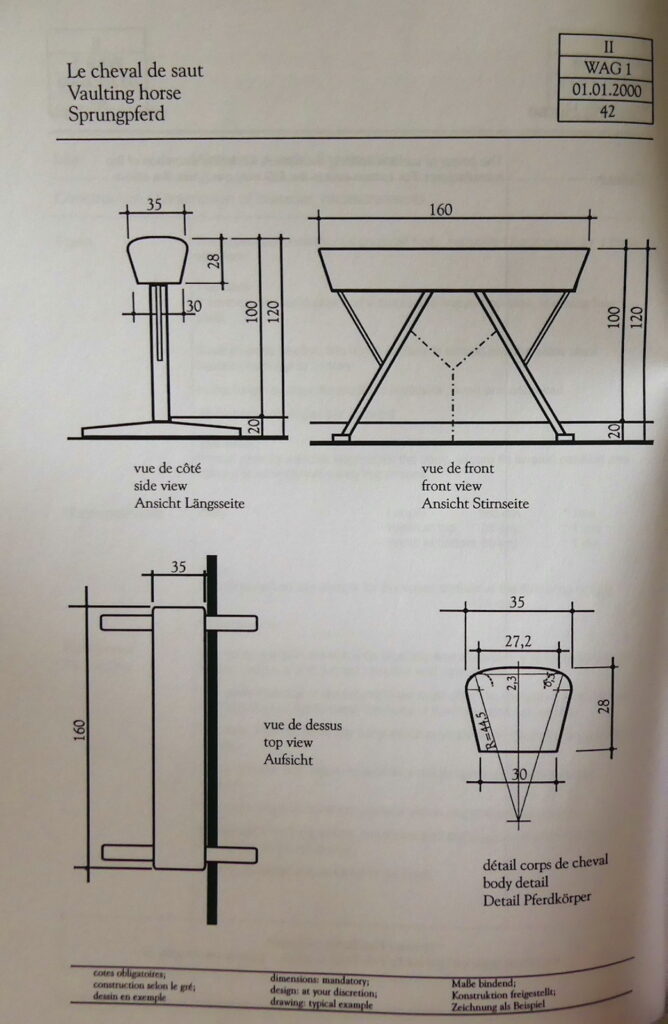

An Error in the Apparatus Norms of 2000

The Apparatus Norms are essentially the rulebook for the dimensions of the apparatus. Whenever the apparatus are set up at a competition, this is the equipment personnel’s bible. The Technical Regulations from 1997 indicated as much:

All competition apparatus must comply with the requirements in the brochure of the “Apparatus Norms” and to any provisions contained in these Regulations and the Codes.

9.1, Technical Regulations, 1997

In early 2000, in preparation for the Sydney Olympics, the FIG issued an updated version of the apparatus booklet. The contents were supposed to be the official guidelines for setting up the apparatus in Sydney.

However, there was a small problem. There was an error in the booklet, and that error was the height of the women’s vault. The document still listed the height as 120 cm when it should have been 125 cm:

The Challenge of Document Control

What do you do when your official guidelines are wrong?

By the time the FIG printed the 2000 Apparatus Norms, the gymnasts had been training and competing on the new vault height for months. The Women’s Technical Committee couldn’t just say, “Surprise! We are going back to 120 cm!” They had to issue a correction to the Apparatus Norms.

In April of 2000, Jackie Fie, President of the Women’s Technical Committee at the time, published a circular to inform the gymnastics community of the error in the apparatus booklet.

But once a document has been printed and disseminated, it’s extremely hard to rectify an error. There’s no way to ensure that everyone reads the circular with the corrections or, more importantly, corrects the error in their apparatus booklets.

And, not to beat a dead vaulting horse, but the apparatus booklets were essential to the process of setting up the equipment at FIG competitions. As mentioned above, Chapter IX of the 1997 Technical Regulations clearly states:

All competition apparatus must comply with the requirements in the brochure of the “Apparatus Norms” and to any provisions contained in these Regulations and the Codes.

9.1, Technical Regulations, 1997

The twisted irony in all of this: during the women’s all-around final, the vault was set correctly, according to the Apparatus Norms, as they were printed in the 2000 booklet. The problem: those norms were wrong.

To be sure, there could have been booklets on the competition floor that crossed out the old height and included the corrected height.

But in my mind, it’s far more plausible that, after the men’s all-around final, a team of equipment personnel had to lower the vault and rotate it sideways. When they went to set the height of the horse, they consulted the Apparatus Norms booklet, as they were supposed to. They looked at the pages for women’s vault (reproduced above). They saw 120 cm in the booklet and set the vault to 120 cm from the floor. They thought that they had done their job correctly because that’s what the Apparatus Norms said. They were unaware of the circular from the Women’s Technical Committee and the corrected vault height.

When a Fail-Safe Fails

If that’s what did indeed happen, the FIG would have had a fail-safe in place to catch these problems. At the time, Slava Corn, a media representative for the FIG, alluded to this system of double-checking the equipment:

Slava Corn, president of the media commission for the Federation Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG) technical committee, said she could not say with any certainty what had gone wrong.

“Numerous individuals–competition managers, technical delegates, head judges–all should check the equipment,” Corn said. “Unfortunately a mistake was made.”

Los Angeles Times, Sept. 22, 2000

More specifically, Chapter IX of the 1997 Technical Regulations stated:

Control of apparatus (and control of publicity on apparatus) before the podium training of a competition will be exercised by the Technical Committee concerned and, if available, assisted by a member of the FIG Apparatus Commission. They control the measurements of the apparatus following the FIG Apparatus Norms and make sure that the apparatus are set correctly, safely, and stable. A report must be made which includes all incorrect items and the necessary adjustments must be made by the Organising Committee and/or the apparatus manufacturer.

9.3, Technical Regulations, 1997

In my reading of this rule,* the Women’s Technical Committee — the officials who wrote the rules and know the apparatus norms by heart — should have been the fail-safe. Even if the grounds crew set the apparatus incorrectly, the Women’s Technical Committee members were responsible for checking the measurements and setting the apparatus “correctly, safely, and stable.”

But they didn’t.

At least not initially.

By the time Allana Slater called attention to the problem during the third rotation, it was too late. Though the Women’s Technical Committee raised the vault to its correct height, half the competitors had already vaulted, and the competition, in my opinion, had already been tainted.

* Note #1

One could read the paragraph from Chapter IX of the 1997 Technical Regulations differently. In this alternate interpretation, the Women’s Technical Committee and the Apparatus Committee would have been responsible solely for checking the equipment prior to podium training. Afterward, it would have been in someone else’s hands — hands that may or may not have known about the error in the apparatus norms. Such a reading, however, does not jibe with Slava Corn’s statement to the press in 2000.

Note #2

In episode 4 of the podcast Blind Landing, Maria Olaru claims that the vault was set improperly during Romania’s podium training. According to her, the vault was 5 cm too low. In the podcast episode, the host wonders how this error could happen twice.

If Olaru’s recollection is correct, my hypothesis would explain how this could have happened more than once. Before podium training, standard protocol would have been in place. The equipment personnel would have likely checked the apparatus norms, as was customary, and an uncorrected apparatus booklet could have been consulted, resulting in a horse set at 120 cm from the ground — 5 cm too low.

5 replies on “2000: The Sydney Vault Debacle and the Apparatus Norms Hypothesis”

That would also explain the theory that the vault was also set too low in some of the preliminary qualification sessions as posited in

https://youtu.be/lxQ0WY6Kt7Q

Thank you for this explanation. I have always wondered what really happened. I really appreciate your research!

The article doesn’t mention that the gymnasts were offered to re-do their vault. However, one or two were injured or shaken from bad landings caused by the height anomaly, and others, including the favourite Svetlana Khorkina, had already progressed to a different piece of apparatus and compounded ‘their error’ on the vault and scored so badly that upping their vault score wouldn’t have helped them with their overall score, so they didn’t bother retrying.

This is an unfortunate example of how incompetent organizers (ie human error) fail athletes and more importantly, are also directly responsible for athletes injuries and any subsequent demise of the athletes. It happens all too often at every level and in every sport, but mainly more artistic sports such a gymnastics, suffer the most human errors. I’ve found the best way to approach meetings is never assume that organizers are competent and always double check their work. Often, organizers are volunteers and sometimes have little experience and even those with experience can be utterly incompetent. It’s all in the details and not everyone can handle the focus required to go into detail. I believe the solution is to ensure coaches themselves take far more responsibility in ensuring their athletes are not in danger. It’s in everyones interest – organizers, coaches, athletes, spectators, sponsors and press. Make a plan, check the plan and check the implementation of the plan, recheck the implementation, find out what parts of the plan have not been implemented correctly and discuss accordingly with safety as the prime concern, not the competition.

I’m sure it was just a coincidence that it was the Australian gymnast that found and pointed the error out. Just a coincidence