In 1963, the Estonian newspaper Spordileht (Sports Magazine) printed a profile of Larisa Latynina. It portrayed Latynina as a well-rounded, caring individual, who fulfilled her responsibilities not just to her sport but also to her daughter, her community, and her country.

When the article was published, Latynina was the reigning World and Olympic all-around champion. On top of her training, she stayed up late answering her fans’ letters (and writing to some coaches with unsolicited advice). Beyond that, she was a “people’s deputy,” an elected position responsible for expressing and defending the public’s interests. (The position still exists in modern-day Ukraine.)

In a way, the article presented a 1960s Soviet version of the “You can have it all” narrative.

Note: Latynina was not the reigning European all-around champion when this article was published. The Soviet Union and other socialist countries refused to attend the 1963 European Championships in France because the East German gymnasts did not receive entry visas.

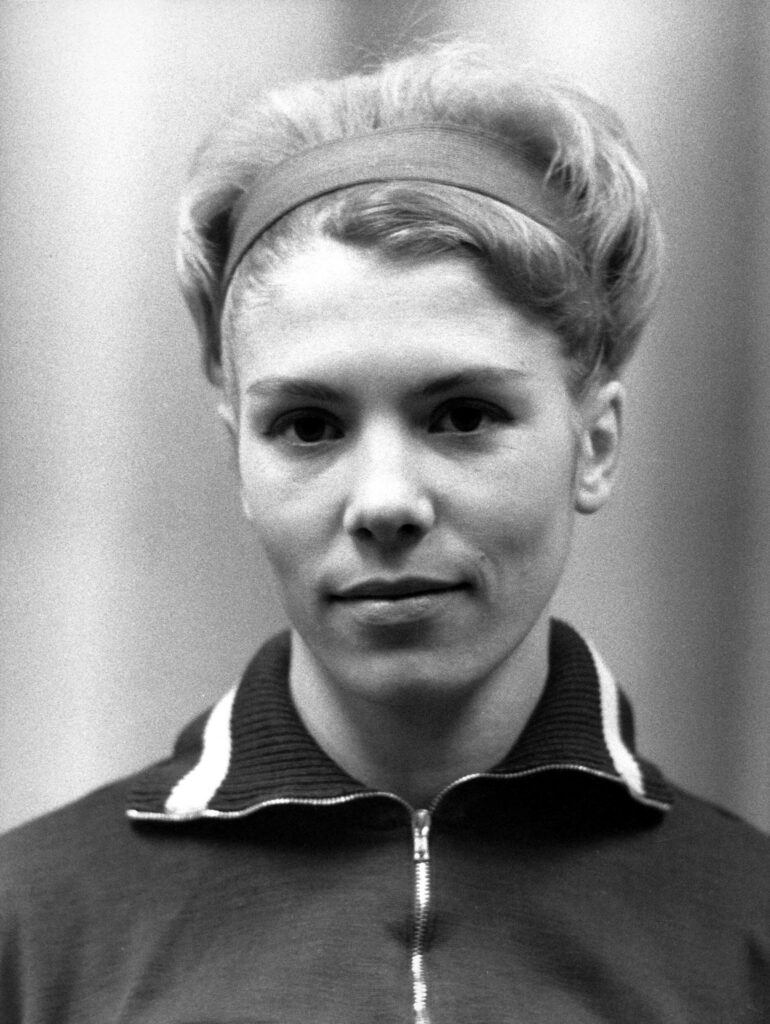

LARISA LATYNINA, a People’s Deputy

“Excuse me, I’ve seen you somewhere,” said an elder visitor to the deputy of the city council “You look like you used to have pigtails tied with a ribbon…”

“Possibly,” smiles the deputy who now has a “more adultlike” hairstyle “But does it matter? Sit down, please, tell me what’s on your mind.”

And the people’s deputy listened to the story about the inappropriate quality of social services. Later, they discussed together what could be done to rectify the matter, and the youth of the intelligent adviser who had supported the citizen no longer bothered the elder at all.

“Meaning, you will help me?” he asked hopefully as he left.

So she forgot to explain where he had seen this young, slender woman, whose movements betrayed either a talented actress or a gymnast.

It was indeed the famous gymnast, world champion, and Olympic all-around champion, meritorious top athlete Larisa Latynina. Already for the second time, she was elected to the Council of Labor People’s Deputies of the City of Kyiv, and the trust of the voters must be justified, as well as the trust of millions of sports fans, who anxiously observe the performance of their favorite in the arena.

People come to deputies and doctors with their problems – be that family issues, a flat on the 4th floor given to a senior citizen, or someone needing a stay at the sanatorium. In order to help people, it is necessary to thoroughly study each individual case. Here, Larisa has great help from her experience as a teacher. The profession of a coach and educator requires tact and the ability to find the way to the human heart.

Once, a woman in work clothes rushed into the deputy’s reception office. She didn’t ask, but demanded, while also waving around the evidence. In short, she left an extremely unpleasant impression. But the deputy sensed that this woman must be right.

And it turned out that she is a single mother who goes to work, and she does not have anyone to help care for her little daughter. [Illegible.] They said that there are no free spots and she would have to wait for some time. That is why the woman came, irritated, directly to get help from the people’s representative.

“You know what?” Latynina interrupted the wounded mother. “If you allow, I will come visit your home.”

“Be my guest!” said the woman now with a calmer tone. Latynina visited her home, met her daughter, and understood the mother’s concern with all her heart, because she is a mother herself. She also has a daughter, Tanya.

They drank tea and talked about their children. In the morning, however, the deputy contacted the managers of the nurseries. There were indeed no free spots. But Larisa convinced them and explained how hard it is for working mothers.

“I believe you have children yourself,” she said to the manager.

And that very same human expression determined the decision.

“Well, okay, we will try to get by temporarily. Let her bring the girl here,” the manager agreed.

Every night before going to bed, Latynina writes down her tasks for the next day. In the morning she works, then trains. The owner of ten Olympic medals plans to add to her collection in Tokyo, so her daily training lasts two to three hours. In addition, Larisa was asked to perform at the factory club – she couldn’t say no to the workers.

Latynina used to write down all her meetings with sports fans. After reaching a hundred of them, she gave up “record-keeping” — the interest of the Soviet people in sports matters of their country exceeded all expectations.

Latynina enters the factory club. The hall is filled with people. There are a number of elderly people with no indication of interest in sports. Some of them are still wearing their work clothes — you can see that the shift has just ended.

Larisa begins her story by observing the audience – are they interested? It seems so. A young man seems to be trying to memorize every word. A mustachioed laborer nods his head in agreement from time to time, and whispers something to his bald neighbor, who then nods. An elderly woman is sitting with a distracted, friendly smile on her face. She is not listening to the speech, she is just glad that a champion athlete, a famous gymnast with an Order of Lenin and an “Order of the Badge of Honor,” is just like any other person, and reminds her of her own daughter.

Late at night, Larisa reads letters. They arrive every day from every corner of the country, from various senders. “Dear Larisa Semyonovna,” reads an angular student’s handwriting, “I want to become a successful athlete, too …” Larisa answers these kinds of letters first. “I am not doing well in gymnastics. It seems that I am talentless,” Moscow schoolgirl Olya G. writes. As a start, Larisa sends her a reassuring letter. She finds out who Olya’s coach is, and writes to him as well, asking him to pay more attention to the girl. Not believing in one’s abilities is the start of many failures. The correspondence continues until one day Larisa reads: “Thank You… I got qualifications and I’m now learning a new routine.” Meaning, everything is great …

This is how the days go by. Doesn’t it get difficult? Because work, however social, is still work. Is there enough time for family, home, everything called personal life?

“Of course there is,” Larisa smiles. “Isn’t everything we do personal life?”

Mark Tartakovski

Spordileht, Sept. 6, 1963

Rahvasaadik LARISSA LATÕNINA

«Vabandage, olen teid kusagil näinud,» lausus linnanõukogu saadikule elatanud külastaja «Teil nagu oleksid tollal olnud paelaga seotud patsikesed …»

«Võimalik,» naeratab saadik, kellel nüüd on «täiskasvanum» soeng «Ent kas sellel on tähtsust? Istuge, palun, rääkige, mis teil südamel.»

Ja rahvasaadik kuulas ära jutustuse ebakohast elukondliku teenindamise alal. Hiljem arutasid nad ühiselt, mida asja parandamiseks ette võtta, ja elatanud kodanikku aruka nõuandja noorus enam sugugi ei seganud.

«Tähendab, te aitate mind?» päris ta lahkudes lootusrikkalt.

Nii ta unustaski selgitada, kus oli näinud seda noort, sihvakat naist, kelle liigutused reetsid kas andekat näitlejat või võimlejat.

See oli tõepoolest kuulus võimleja absoluutne maailmameister ja olümpiavõitja, teeneline meistersportlane Larissa Latõnina Juba teistkordselt valiti ta Kiievi Linna Töörahva Saadikute Nõukogusse ning valijate usaldust tuleb õigustada, samuti nagu miljonite spordihuviliste usaldust, kes ärevusega jälgivad oma lemmiku esinemist maa-ilma-areenil.

Rahvasaadiku ning arsti juurde tullakse hädadega. Kas on kellelgi perekondlikud pahandused või on vanakestele antud korter neljandale korrusele. Kellelgi on viibimata vaja sanatooriumiravi. Selleks et inimesi aidata, on vaja iga üksikjuhtumiga põhjalikult tutvuda. Siin on Larissal suur abi oma pedagoogikogemustest. Treeneri ja kasvataja elukutse nõuab taktitunnet, oskust leida teed inimsüdamesse.

Kord tormas rahvasaadiku vastuvõtutöötuppa tööriietes naine. Ta ei’ palunud, vaid otse nõudis, ise seejuures peatäit tõendeid vibutades Lühidalt ta jättis äärmiselt ebameeldiva mulje. Kuid rahvasaadik tajus, et sel naisel peab olema tuline õigus.

Ja selguski, et ta on üksik ema, käib tööl, pisitütart pole aga kellegi hooleks jätta [illegible] medes öeldud, et ruumi ei ole ja tal tuleb mõni aeg oodata. Sellepärast naine tuligi ärritatult otse rahvasaadikult abi saama.

«Teate, mis?» katkestas Latõnina haavunud ema kõnevoolu. «Kui lubate, tulen teiega koju kaasa.»

«Olge lahke!» jättis naine sedamaid kõrgendatud tooni. Latõnina külastas tema kodu, nägi tüdrukukest, mõistis kõigest hingest ema muret, sest tema ise on ju ka ema Temalgi on tütreke Tanja.

Nad jõid teed, jutlesid oma lastest. Hommikul aga astus rahvasaadik ühendusse lastesõimede juhatajatega. Vabu kohti tõepoolest ei olnud. Kuid Larissa veenis ja s letis, kui raske on töötavatel emadel.

«Usun, et teil endalgi on lapsed,» ütles ta juhatajale.

Ja seesama lihtne inimlik väljendus otsustas.

«Noh, olgu, katsume ajutiselt kitsamini läbi ajada. Las ta toob tüdruku siia,» nõustus juhataja.

Õhtuti enne magamaheitmist paneb Latõnina kirja oma homsed ülesanded. Hommikul töö, siis treening. Kümne olümpiamedali omanikul on kavas oma kollektsiooni täiendamine Tokios Seepärast kestab tema igapäevane treening kaks-kolm tundi. Peale selle oli Larissat palutud tehaseklubisse esinema — töölistele muidugi ära öelda ei võinud.

Kunagi varem tähendas Latõnina üles kõik oma kohtumised spordihuvilistega. Jõudnud sajani, ta loobus «arvepidamisest» — nõukogude inimeste huvi oma maa spordiküsimuste vastu ületas kõik ootused.

Ja Latõnina siseneb tehaseklubisse. Viimase võimaluseni täis saal. On ka hulk elatanud

inimesi, kelles pealtnäha miski ei reeda spordihuvilisi. Mõnel on alles tööriidedki seljas — näha, et vahetus äsja lõppes.

Larissa alustab oma jutustust, ise pealtvaatajaid jälgides: kas huvitab? Näib, et küll. Üks noormees nagu püüaks iga sõna talletada. Vurrudega tööline noogutab aeg-ajalt nõusolevalt pead, sosistab midagi kiilaspäisele naabrile, ja temagi noogutab. Vanem naine istub, hajameelne heasüdamlik naeratus näol. Ega ta kõnet kuulagi, tal on lihtsalt hea meel, et teeneline meistersportlane, kuulus võimleja, kellel on Lenini orden ja «Austuse märk», on päris samasugune kui teisedki inimesed, pealegi meenutab talle ta enda tütart.

Hilja õhtul loeb Larissa kirju. Neid tuleb iga päev kodumaa igast nurgast ja saatjaidki on mitmesuguseid. «Austatud Larissa Semjonovna,» algavad nurgelise õpilaskäekirjaga veetud reed. «Mira tahan ka heaks sportlaseks saada …» Sellistele kirjadele vastab Larissa esimeses järjekorras. «Mul ei taha võimlemisega sugugi edasi minna. Näib, et olen andetu,» kirjutab Moskva koolitüdruk Olja G. Temale saadab Larissa julgustava kirja seda alguseks. Ta uurib välja, kes on Olja treener, ja kirjutab temalegi, palub suhtuda tütarlapsesse tähelepanelikult. Enda võimetesse mitte uskuda see on paljude ebaõnnestumiste algus. Kirjavahetus kestab. Ja ühel päeval Larissa loeb: «Tänan Teid… Sain spordijärgu ja õpin nüüd uut kava.» Tähendab, kõik on korras …

Nii möödub päev päeva kõrval. Kas raskeks ei lähe? Sest töö olgugi ühiskondlik jääb ikkagi tööks. Kas piisab aeg i perekonnale, kodule, kõigele sellele, mida nimetatakse isiklikuks eluks?

«Muidugi piisab,» naeratab Larissa. «Kas kõik hea, mida teeme, polegi siis meie isiklik elu?»

Mark Tartakovski

Note: This article is interesting, in part, because it discusses Latynina’s work as a people’s deputy. Latynina did not write much about her role on the city council in her autobiography titled Balance. Here’s a small excerpt:

What does the winner get?

Awards? Yes, I was awarded with the highest order of our country, I’ll have to justify it for the rest of my life.

Recognition? Yes, and to such extent that it made me feel uneasy. Of course, I already knew a lot in gymnastics but what kind of a City Council member I will be in such as city as Kyiv? Of course, I did tasks given to me by Komsomol but what I’d be able to do as the member of the Komsomol’s Central Committee of our big republic?

Fame? It comes to an athlete right with the victory. You hear such words, such magnificent epithets that you feel uncomfortable. Yesterday you was equal to your girlfriends. Today you’re called “first among equal” but everyone talks only about you. And it makes sense – you’re the champion. The fight was so difficult, the rivals were so dangerous, and the victory was so hard. So, does it mean that you deserve everything that is said about you?

Balance, Chapter 6, Larisa Latynina

Note #2: As we’ll see later, Soviet gymnasts visiting factories was a common theme in the press.

Appendix: The Boycott of the 1963 European Championships

In 1963, Paris, France, hosted the Women’s European Championships. But there was a problem: France did not recognize the East German government. (It wouldn’t recognize the East German government until 1973.) As a result, the French government refused to give entry visas to the GDR gymnasts for the competition. In solidarity with the East German gymnasts, the Eastern bloc refused to participate in the championships.

Here’s what the Hungarian press conveyed:

Another discrimination against GDR athletes

The Hungarian gymnasts will not compete in the European Cup in Paris out of solidarity

This year’s Women’s Gymnastics European Cup will be held in Paris on April 20 and 21. After the athletes of the GDR did not receive an entry permit, the Hungarian competitors agreed to show solidarity and will not take part in the competition. In this regard, the President of the Hungarian Gymnastics Federation asked the Hungarian Telegraph Office to communicate the following:

“We were informed that the GDR gymnasts were not allowed to travel to France for the European Cup of women’s gymnastics, and the FIG (International Gymnastics Federation) will organize the competition despite this. This is discriminatory against a country that is a full member of the International Gymnastics Federation. The decision goes against the Lausanne recommendations of the IOC and the basic rules of the International Gymnastics Federation. We are very sorry that such a situation has arisen, which, as we well know, is unpleasant for the FIG and the French Gymnastics Federation. Nevertheless, we decided that, under the given circumstances, we would stand in solidarity with the GDR gymnasts and not participate in the competition in Paris. We hope that the FIG will find a way out so that our sport is not exposed to such upheaval and danger in the future.”

Népszabadság, April 13, 1963

Újabb diszkrimináció az NDK-sportolókkal

A magyar tornásznak szolidaritásból nem indulnak a párizsi Európa Kupában

Párizsban április 20-án és 21-én rendezik meg az idei női tornász Európa Kupát. Miután az NDK sportolói nem kaptak beutazási engedélyt, a magyar versenyzők szolidaritást vállaltak, és nem indulnak a versenyen. Ezzel kapcsolatban a Magyar Torna Szövetség elnöksége a következők közlésére kérte fel a Magyar Távirati Irodát:

„Értesültünk arról, hogy az NDK tornásznál nem kaptak beutazási engedélyt Franciaországba, a női torna Európa Kupa versenyeire, s a FIG (Nemzetközi Torna Szövetség) ennek ellenére megrendezi a versenyt. Ez megkülönböztetést jelent egy olyan országgal szemben, amely teljes jogú tagja a Nemzetközi Torna Szövetségnek. A döntés ellenkezik a NOB lausanne-i ajánlásaival és a Nemzetközi Torna Szövetség alapszabályaival. Nagyon sajnáljuk, hogy ilyen helyzet állt elő, amely, jól tudjuk, a FIG és a Francia Torna Szövetség számára is kellemetlen. Mégis úgy döntöttünk, hogy az adott körülmények között az NDK-tornászokkal szolidaritást vállalunk és nem veszünk részt a párizsi versenyen. Reméljük, hogy a FIG megtalálja a kivezető utat, nehogy sportágunk a jövőben is ilyen megrázkódtatásnak és veszélynek legyen kitéve.”

And here’s what the Romanian press stated:

A DISCRIMINATORY ACTION BY THE FRENCH AUTHORITIES PREVENTS THE “EUROPEAN CUP” IN GYMNASTICS

On April 20 and 21, the “European Cup” for women’s gymnastics was to be held in Paris. Following a policy of discrimination against athletes from the German Democratic Republic, the French authorities refused to grant entry visas to the representatives of the German Democratic Republic. On the other hand, the International Gymnastics Federation, whose president is Charles Thoeni, did not take the necessary measures to ensure normal conditions for the competition.

Consequently, the gymnastics federations of the U.S.S.R., Romania, Poland, and the other socialist countries sent letters to the International Gymnastics Federation announcing that the gymnasts from these countries refuse to come to Paris to take part in the “European Cup.”

Sportul, April 16, 1963

O ACȚIUNE DISCRIMINATORIE A AUTORITĂȚILOR FRANCEZE ÎMPIEDICĂ DESFĂȘURAREA „CUPEI EUROPEI“ LA GIMNASTICĂ

La 20 și 21 aprilie urma să se desfășoare la Paris „Cupa Europei“ la gimnastică pentru femei. Urmând o politică de discriminare față de sportivii din R. D. Germană, autoritățile franceze au refuzat să acorde viza de intrare in Franța reprezentantelor R. D. Germane. Pe de altă parte, Federația internațională de gimnastică, al cărei președinte este Charles Thoeni, nu a luat măsurile necesare in vederea asigurării condițiilor normale de desfășurare a competiției.

In consecință, federațiile de gimnastică din U.R.S.S., R. P. Romină, R. P. Polonă și celelalte țări socialiste au trimis scrisori Federației internaționale de gimnastică prin care anunță că gimnastele din aceste țări refuză să vină la Paris pentru a lua parte la „Cupa Europei“.