On July 3, 1980, inside the Minsk Sports Palace, Elena Mukhina attempted a skill she had never mastered. “The injury was inevitable anyway,” she would say in her first interview after her accident. “Not necessarily on that day. It seems to me they would have carried me away from the competition floor sooner or later because I just couldn’t do that element.” Her coach was out of town. The home Olympics were days away. And the doctors wouldn’t protect her because, as she insisted, they “don’t serve health, they serve sport.”

Mukhina described running laps on a leg that hadn’t healed to shed weight, arriving at the gym two hours early, exhausting herself before training even began. “I was stupid. I really wanted to justify their trust, to be a heroine.” When she fell for the last time, her first thought was relief: “Thank God, I won’t make it to the Olympics.”

She came to see her story less as a personal tragedy than as evidence of a culture that exploited children’s small vision of the world. “If only we started doing sports at sixteen or eighteen, when a person can already consciously choose their path, and not at nine or ten, when we see nothing around us except sports—an interest so artfully stoked. It seems to us that this is some kind of special world. We don’t yet know how narrow this three-dimensional space is—gym, home, training camps.”

Even in paralysis, the discipline lingered. “In the first years after the injury, when I was just lying there, it felt wild to me that nothing was required of me. I so needed this feeling of at least some kind of overcoming that I started to starve myself, just like that. To torment myself. A habit…”

And yet, Mukhina refused to frame herself as a martyr or her coaches as villains. Instead, she blamed a pervasive lack of agency and silence. “There are such notions as the honor of the club, the honor of the team, the honor of the national team, the honor of the flag. They are words behind which you can’t see the person. I don’t condemn anyone and don’t blame anyone for what happened to me. Not Klimenko, and even less the then national-team coach, Shaniyazov. I feel sorry for Klimenko—he’s a victim of the system. I simply don’t respect Shaniyazov. And the others? I was injured because everyone around me maintained neutrality, kept silent. They saw that I wasn’t ready to perform this element. But they were silent. No one stopped the person who, forgetting everything, rushed forward—come on! Come on! Come on!”

What follows is a translation of “Grown-up Games,” which ran in Ogonyok in July of 1988 — eight years after her accident.

Note: I have placed the quotes from Mukhina in italics, even though they aren’t highlighted in the original. It’s easy to read this piece and confuse Mukhina’s first-person statements with the author’s.

Note #2: This is the third post in a four-part series. I’d recommend first reading

- Part 1 (What the Soviet Union Printed about Mukhina’s Accident)

- Part 2 (What the Rest of the World Printed about Mukhina’s Accident).

After reading this interview, you can read a 1989 interview with her, as well. (Elena Mukhina Addresses the Myths in “After Fame, After Tragedy”)

Grown-up Games

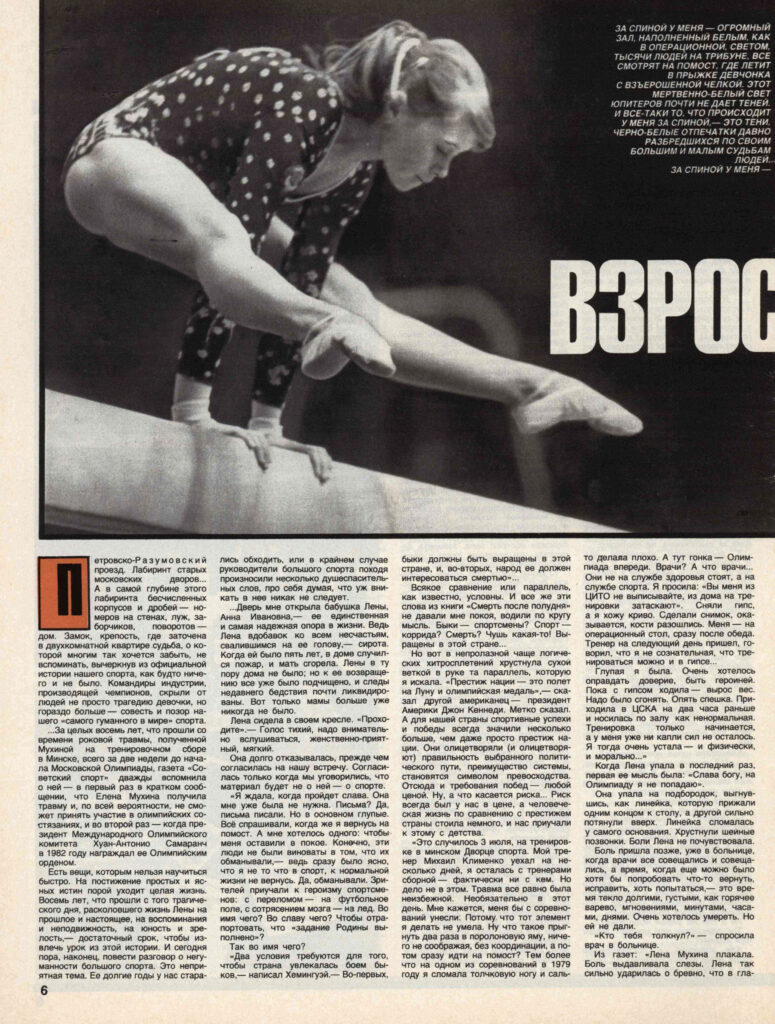

Behind me is a vast hall, filled with white light like in an operating room, thousands of people in the stands. Everyone is watching the podium, where a girl with tousled bangs is flying in a leap. That deathly white light from the spotlights hardly casts any shadows. And yet what’s happening behind me are shadows—black-and-white imprints of people long since scattered to their greater and lesser destinies.

Behind me is a reinforced-concrete wall; on the wall, pink floral wallpaper; on the wallpaper, a large photograph of a huge arena, thousands of people in the stands, and a girl with tousled bangs who is flying, flying, and, it seems, will never be able to land.

She sits before me in a wheelchair, her hands resting on the armrests—neatly coiffed and even lightly made-up—Elena Mukhina.

Petrovsko-Razumovsky Lane. A labyrinth of old Moscow courtyards… And at the very heart of this labyrinth—endless corridors and fractions, numbers scrawled on walls, puddles, little fences—stands an apartment building. A castle, a fortress, where fate is imprisoned in a two-room apartment, a fate so many long to forget, to strike from the official history of our sport as if it had never happened. The commanders of the industry that produces champions concealed from the people not merely a girl’s tragedy, but something far greater: the conscience and disgrace of our “most humane sport in the world.”

…In the eight whole years since the fatal injury Mukhina sustained at a training camp in Minsk—just two weeks before the start of the Moscow Olympics—the newspaper Sovetsky Sport mentioned her twice:* first in a brief note that Elena Mukhina had been injured and would, in all likelihood, be unable to take part in the Olympic competitions; and the second time when IOC president Juan Antonio Samaranch, in 1982, awarded her the Olympic Order.

[*Note: As we saw, Mukhina appeared in Sovetsky Sport more than twice.]

There are things you cannot learn quickly. Sometimes it takes a whole lifetime to grasp simple, clear truths. The eight years since that tragic day—which split Lena’s life into past and present, into memories and immobility, into youth and maturity—are long enough to draw a lesson from this story. And today it is finally time to speak about the inhumanity of elite sports. It’s an unpleasant subject. For many years, we tried to skirt it, or, at most, high-ranking sports officials would toss off a few consoling words, thinking to themselves that it was best not to delve deeply into it.

…The door was opened for me by Lena’s grandmother, Anna Ivanovna—her only and most reliable support in life. After all, Lena, in addition to all the misfortunes that fell on her head, is an orphan. When she was five years old, there was a fire in the house, and her mother was burned to death. Lena wasn’t home at the time, but by her return, everything had already been cleaned up, and traces of the recent disaster were almost eliminated. Only her mother was never there again.

Lena was sitting in her chair. “Come in.” The voice is quiet; you have to listen carefully. It was femininely pleasant and soft.

She refused for a long time before agreeing to our meeting. She agreed only when we agreed that the piece would not be about her but about sports.

“I was waiting for the fame to pass. I no longer needed it. Letters? Yes, they wrote letters. But mostly stupid ones. They all asked when I would return to the podium. And I wanted only one thing: to be left alone. Of course, these people weren’t to blame for being deceived—after all, it was immediately clear that I wouldn’t return not just to sports, but to normal life. Yes, they were deceived. Spectators were trained to expect heroics from athletes: a broken bone—onto the soccer field; a concussion—onto the ice. In the name of what? For the glory of what? To report that ‘the Motherland’s task has been fulfilled’?”

So, in the name of what?

“Two conditions are required for a country to be fascinated by bullfighting,” wrote Hemingway. “First, the bulls must be raised in that country, and second, its people must be interested in death”…

Any comparison or parallel is, as we know, approximate. And yet these words from the book Death in the Afternoon gave me no peace and sent my thoughts spinning in circles. Are the bulls athletes? Is sport a bullfight? Death? Utter nonsense! Raised in this country…

But there, in the impenetrable thicket of logical intricacies, that parallel I was looking for cracked like a dry branch in my hand. “National prestige is a flight to the Moon and an Olympic medal,” said another American, U.S. President John Kennedy. Well said. And for our country, sporting successes and victories have always meant somewhat more than even just national prestige. They embodied (and still embody) the correctness of the chosen political path, the advantage of the system; they become a symbol of superiority. Hence, the demands for victories—at any cost. Well, as for risk… Risk was always valued among us, and human life compared to the country’s prestige was worth little. We were taught this from childhood.

“It happened on July 3, during training at the Minsk Sports Palace. My coach, Mikhail Klimenko, had left for a few days, and I was left with the national team coaches—in effect, with no one. But that’s not the point. The injury was inevitable anyway. Not necessarily on that day. It seems to me they would have carried me away from the competition floor sooner or later because I just couldn’t do that element. What good is it to tumble twice into a foam pit, understanding nothing, without coordination, and then immediately go up to the podium? Especially since at one of the competitions in 1979, I broke my takeoff leg and did saltos poorly. But the race was on—the Olympics were ahead. Doctors? What about the doctors… They don’t serve health, they serve sport. I begged: ‘Don’t discharge me from CITO [Central Institute of Traumatology and Orthopedics], they’ll drag me from home to training.’ They removed the cast, and I walked crookedly. They took an X-ray, and it turned out the bones had separated. I went straight to the operating table, right after lunch. The coach came the next day, said I wasn’t conscientious, that you can train even in a cast…

“I was stupid. I really wanted to justify their trust, to be a heroine. While I walked with the cast, I gained weight. I had to lose it. Rush again. I came to CSKA two hours early and ran around the hall like crazy. The workout was just beginning, and I already didn’t have a drop of strength left. I was so tired then—both physically and morally…”

When Lena fell for the last time, her first thought was: “Thank God, I won’t make it to the Olympics.”

She fell on her chin, arched like a ruler that was pressed at one end to the table, and the other end was pulled strongly upward. The ruler snapped at the very base. The cervical vertebrae crunched. Lena felt no pain.

The pain came later, already in the hospital, when the doctors kept conferring and conferring, while the time when it might still have been possible to at least try to restore something, to fix it, to at least attempt it—this time flowed in long, thick moments, minutes, hours, days, like hot stew. She desperately wanted to die. But they wouldn’t let her.

“Who pushed you?” asked the doctor in the hospital.

From newspapers: “Lena Mukhina was crying. Pain squeezed out tears. Lena hit the beam so hard that everything went dark before her eyes. It was very painful to step on her foot. But there remained the last event—floor exercise. She decided, ordered herself: ‘I have to work! I have to give everything!’ And she went to the mat… Klimenko was terribly pleased: ‘Well, there, I see a real fighter in her. She has character, that she does!'”

“…Mikhail Klimenko came to women’s gymnastics from men’s; he had firmly mastered techniques that are more complex than women’s. He’s a rationalist and a logician. The path to achieving courage lies through conviction, through the brain to the muscles…”

“…You know when I get really scared? When I watch my uneven bars routine on television…”

If we divide humanity into children and adults, and life into childhood and maturity, then there are many children and much childhood in life. Only we, immersed in our struggle and our concerns, don’t notice them… We’ve arranged things so that children interfere with us as little as possible and guess what we really represent as little as possible. These words were spoken long ago by an educator who earned worldwide recognition. But the thing is, these words still haven’t lost their relevance. On the contrary, when applied to sports, they’ve acquired a sinisterly ugly nuance. Allow me such an allegory: a healthy, cheerful person (and now more and more often a child) gets into the brightly painted, elegant, and attractive machine of big sports. The machine carries him in circles. At first, everything seems fascinating, such an amusing attraction, but the speed climbs higher, the centrifugal force grows, the workloads get heavier. And then, when the machine finally stops, an invalid emerges from it, crippled both physically and morally. Physically, because you can’t discount numerous dislocations, fractures, concussions. Morally, because someone used to living amid universal attention and reverence cannot adjust to a lower level, and after leaving elite sport, feels needed by no one.

“If only we started doing sports at sixteen or eighteen, when a person can already consciously choose their path, and not at nine or ten, when we see nothing around us except sports—an interest so artfully stoked. It seems to us that this is some kind of special world. We don’t yet know how narrow this three-dimensional space is—gym, home, training camps. And even though athletes travel so much and see so much, spiritually, they are terribly deprived. Training loads, training loads, training loads. Nothing exists except training loads, which constantly grow, and it sometimes seems that that’s it, you don’t have any strength left to give. But the coach once told me: ‘Until you break, no one will let you go.’

“I became so accustomed to forcing myself—don’t want to, scared, can’t eat, can’t drink—that in the first years after the injury, when I was just lying there, it felt wild to me that nothing was required of me. I so needed this feeling of at least some kind of overcoming that I started to starve myself, just like that. To torment myself. A habit…”

I often remember one episode from the life of our celebrated Olympic figure skating champion Irina Rodnina. Remember when she fell from a lift in practice, hit her head on the ice, they took her to the hospital with a severe concussion, and a few days later, still with that same concussion, she competed and won? Our little, courageous woman, Rodnina. Many newspaper articles were written in praise of her courage, then TV films were made, and even books were written. But I ask myself again and again: Why did she have to be forced onto the ice in a semi-conscious state? And if she did it of her own free will, who hypnotized her with the thought that “Moscow stands behind us,” that “there is nowhere to retreat”? This isn’t war! Sport is a noble endeavor!

“There are such notions as the honor of the club, the honor of the team, the honor of the national team, the honor of the flag. They are words behind which you can’t see the person. I don’t condemn anyone and don’t blame anyone for what happened to me. Not Klimenko, and even less the then national-team coach, Shaniyazov. I feel sorry for Klimenko—he’s a victim of the system, a member of the clan of grown men who do ‘business.’ I simply don’t respect Shaniyazov. And the others? I was injured because everyone around me maintained neutrality, kept silent. They saw that I wasn’t ready to perform this element. But they were silent. No one stopped the person who, forgetting everything, rushed forward—come on! Come on! Come on!”

It cannot be said that the changes taking place in our lives have not touched sports, say, artistic gymnastics. For instance, its leaders have decided that, from now on, it will be more spectacular and more feminine. That is, at last, on the podium, we will not see girls with the bodies of kindergarteners, but… Leonid Arkayev, head of the gymnastics department of the USSR State Sports Committee, announced this in all seriousness at a press conference marking the opening of yet another Moscow News tournament. He proudly named the gymnasts we have been seeing on the podium for several years now and who, despite their age, no offense to them, still scarcely resemble women. And he also said at that same press conference that there is not a single athlete in modern artistic gymnastics who competes at the international elite level and has not been injured. True, he added that this was “not for publication” (imagine: at a press conference—“not for publication”!). We obediently nodded. But I still allow myself to repeat this revelation, because, first, these are the times we live in, and second, I’m sure it won’t affect Arkayev’s career in any way. Who cares about injuries when our gymnastics is at the vanguard of world sport? Against a crowbar, as they say, there’s no defense.*

[*Note: We don’t have a similar idiomatic phrase in English. The idea is essentially, “When brute force comes into play, there’s no trick that will save you.”]

A picky reader might object: after all, in the West, abroad, athletes are placed in the same conditions; they, too, have to risk and sacrifice their health. Yes, I’m forced to agree. But there’s one small “but.” There, “over there,” athletes do this in the name of fabulous amounts of money, in the name of a secure future for themselves and for their families. Here, for so long, they filled people’s heads so well with the fake notion that sports are of an amateur nature that it wasn’t clear at all: Why? Why did they do it? So that the State Committee for Sports functionaries could boastfully report…

I am far from thinking we should blame sport for all sins—sport is a wonderful and noble invention of humankind. Moreover, one of the main achievements of the new socio-economic system was precisely sports: mass sports, accessible to everyone. But gradually, as with many other areas of our lives, sports moved out of everyday life and onto the squares of May Day parades and into cheerful newsreels. Fake mass participation took hold. Inflated numbers of “physical-culture enthusiasts,” the moribund GTO [Ready for Labor and Defense] complex, which they’re trying in vain to resuscitate, crumbling stadiums, and the absence of any kind of sports clothing. And against this backdrop—brilliant victories, soaring flags, and tears in the eyes of winners.

“To the mentors who guarded our youth…”* Sport is the lot of the young. But behind it stand quite adult people, playing quite adult games. They need to change their attitude toward sport. Or they need to be changed. After all, Elena Mukhina’s fate is just the tip of an enormous iceberg of crippled destinies. Let us think about this.

[*Note: This is a line from Alexander Pushkin’s Lyceum poem “19 октября” (“October 19th”), which he wrote in exile.]

Ogonyok, no. 29, July 29, 1988, no. 29

Oksana POLONSKAYA

Photo by Anatoly BOCHININ.

Взрослые игры

За спиной у меня — огромный зал, наполненный белым, как в операционной, светом, тысячи людей на трибуне. Все смотрят на помост, где летит в прыжке девчонка с взъерошенной челкой. Этот мертвенно-белый свет юпитеров почти не дает теней. И все-таки то, что происходит у меня за спиной, — это тени. Черно-белые отпечатки давно разбредшихся по своим большим и малым судьбам людей.

За спиной у меня — железобетонная стена, на стене — розовые обои в цветочек, на обоях — большая фотография огромного зала, тысячи людей на трибунах и девчонка с взъерошенной челкой, которая летит, летит и, кажется, никогда уже не сможет приземлиться.

Она сидит передо мной в инвалидном кресле, руки покоятся на подлокотниках, аккуратно причесанная и даже чуть подкрашенная Елена Мухина.

***

Петровско-Разумовский проезд. Лабиринт старых московских дворов…

А в самой глубине этого лабиринта — бесчисленных коридоров и дробей — номера на стенах, лужи, заборчики, поворотное дом. Замок, крепость, где заточена в двухкомнатной квартире судьба, о которой многим так хочется забыть, не вспоминать, вычеркнуть из официальной истории нашего спорта, как будто ничего и не было. Командиры индустрии, производящей чемпионов, скрыли от людей не просто трагедию девочки, но гораздо больше — совесть и позор нашего «самого гуманного в мире» спорта.

…За целых восемь лет, что прошли со времени роковой травмы, полученной Мухиной на тренировочном сборе в Минске, всего за две недели до начала Московской Олимпиады, газета «Советский спорт» дважды вспомнила о ней — в первый раз в кратком сообщении, что Елена Мухина получила травму и, по всей вероятности, не сможет принять участие в олимпийских состязаниях, и во второй раз — когда президент Международного Олимпийского комитета Хуан-Антонио Самаранч в 1982 году награждал ее Олимпийским орденом.

Есть вещи, которым нельзя научиться быстро. На постижение простых и ясных истин порой уходит целая жизнь. Восемь лет, что прошли с того трагического дня, расколовшего жизнь Лены на прошлое и настоящее, на воспоминания и неподвижность, на юность и зрелость,— достаточный срок, чтобы извлечь урок из этой истории. И сегодня пора, наконец, повести разговор о негуманности большого спорта. Это неприятная тема. Ее долгие годы у нас старались обходить, или в крайнем случае руководители большого спорта походя произносили несколько душеспасительных слов, про себя думая, что уж вникать в нее никак не следует.

…Дверь мне открыла бабушка Лены, Анна Ивановна,— ее единственная и самая надежная опора в жизни. Ведь Лена вдобавок ко всем несчастьям, свалившимся на ее голову,— сирота. Когда ей было пять лет, в доме случился пожар, и мать сгорела. Лены в ту пору дома не было; но к ее возвращению все уже было подчищено, и следы недавнего бедствия почти ликвидированы. Вот только мамы больше уже никогда не было.

Лена сидела в своем кресле. «Проходите».— Голос тихий, надо внимательно вслушиваться, женственно-приятный, мягкий.

Она долго отказывалась, прежде чем согласилась на нашу встречу. Согласилась только когда мы уговорились, что материал будет не о ней — о спорте.

«Я ждала, когда пройдет слава. Она мне уже была не нужна. Письма? Да, письма писали. Но в основном глупые. Всё спрашивали, когда же я вернусь на помост. А мне хотелось одного: чтобы меня оставили в покое. Конечно, эти люди не были виноваты в том, что их обманывали,— ведь сразу было ясно, что я не то что в спорт, к нормальной жизни не вернусь. Да, обманывали. Зрителей приучали к героизму спортсменов: с переломом — на футбольное поле, с сотрясением мозга — на лед. Во имя чего? Во славу чего? Чтобы отрапортовать, что «задание Родины выполнено»?

Так во имя чего?

«Два условия требуются для того, чтобы страна увлекалась боем быков,— написал Хемингуэй.— Во-первых, быки должны быть выращены в этой стране, и, во-вторых, народ ее должен интересоваться смертью»…

Всякое сравнение или параллель, как известно, условны. И все же эти слова из книги «Смерть после полудня» не давали мне покоя, водили по кругу мысль. Быки— спортсмены? Спорт — коррида? Смерть? Чушь какая-то! Выращены в этой стране…

Но вот в непролазной чаще логических хитросплетений хрустнула сухой веткой в руке та параллель, которую я искала. «Престиж нации — это полет на Луну и олимпийская медаль»,— сказал другой американец — президент Америки Джон Кеннеди. Метко сказал. А для нашей страны спортивные успехи и победы всегда значили несколько больше, чем даже просто престиж нации. Они олицетворяли (и олицетворяют) правильность выбранного политического пути, преимущество системы, становятся символом превосходства. Отсюда и требования побед— любой ценой. Ну, а что касается риска… Риск всегда был у нас в цене, а человеческая жизнь по сравнению с престижем страны стоила немного, и нас приучали к этому с детства.

«Это случилось 3 июля, на тренировке в минском Дворце спорта. Мой тренер Михаил Клименко уехал на несколько дней, я осталась с тренерами сборной— фактически ни с кем. Но дело не в этом. Травма все равно была неизбежной. Необязательно в этот день. Мне кажется, меня бы с соревнований унесли: Потому что тот элемент я делать не умела. Ну что такое прыгнуть два раза в поролоновую яму, ничего не соображая, без координации, а потом сразу идти на помост? Тем более что на одном из соревнований в 1979 году я сломала толчковую ногу и сальто делала плохо. А тут гонка — Олимпиада впереди. Врачи? А что врачи… Они не на службе здоровья стоят, а на службе спорта. Я просила: «Вы меня из ЦИТО не выписывайте, из дома на тренировки затаскают». Сняли гипс, а я хожу криво. Сделали снимок, оказывается, кости разошлись. Меня — на операционный стол, сразу после обеда. Тренер на следующий день пришел, говорил, что я не сознательная, что тренироваться можно и в гипсе…

Глупая я была. Очень хотелось оправдать доверие, быть героиней. Пока с гипсом ходила— вырос вес. Надо было сгонять. Опять спешка. Приходила в ЦСКА на два часа раньше и носилась по залу как ненормальная. Тренировка только начинается, а у меня уже ни капли сил не осталось. Я тогда очень устала— и физически, и морально…»

Когда Лена упала в последний раз, первая ее мысль была: «Слава богу, на Олимпиаду я не попадаю».

Она упала на подбородок, выгнувшись, как линейка, которую прижали одним концом к столу, а другой сильно потянули вверх. Линейка сломалась у самого основания. Хрустнули шейные позвонки. Боли Лена не почувствовала.

Боль пришла позже, уже в больнице, когда врачи все совещались и совещались, а время, когда еще можно было хотя бы попробовать что-то вернуть, исправить, хоть попытаться,— это время текло долгими, густыми, как горячее варево, мгновениями, минутами, часами, днями. Очень хотелось умереть. Но ей не дали.

«Кто тебя толкнул?» — спросила врач в больнице.

Из газет: «Лена Мухина плакала. Боль выдавливала слезы. Лена так сильно ударилась о бревно, что в глазах потемнело. Наступать на ногу было очень больно. И оставался последний вид — вольные. Она решила, приказала себе: «Надо работать! Надо отдать все!» И пошла на ковер… Клименко был страшно доволен: «Ну вот, я вижу в ней настоящего бойца. Есть характер, есть!»

«…Михаил Клименко пришел в женскую гимнастику из мужской, он прочно усвоил технику, которая посложнее женской. Он — рационалист и логик. Путь достижения смелости лежит через убеждение, через мозг к мышцам…»

«…Знаете, когда мне по-настоящему страшно становится? Когда я свою комбинацию на брусьях по телевизору смотрю…»

Если поделить человечество на детей и взрослых, а жизнь— на детство и зрелость, то детей и детства в жизни очень много. Только погруженные в свою борьбу и в свои заботы мы их не замечаем… Мы устроились так, чтобы дети нам как можно меньше мешали и как можно меньше догадывались, что мы на самом деле собой представляем. Эти слова сказаны давным-давно педагогом, который снискал себе всемирное признание. Но в том-то и штука, что слова эти до сих пор не утратили своей актуальности. Наоборот, применительно к спорту они приобрели зловеще уродливую окраску. Позволю себе такую аллегорию: в ярко раскрашенную, нарядную и привлекательную машину большого спорта садится здоровый жизнерадостный человек (а сейчас все чаще и ребенок). Машина мчит его кругами, сначала все кажется увлекательным, таким забавным аттракционом, но скорость все выше, центробежная сила все больше, нагрузки все сильнее. И вот, когда наконец машина останавливается, из нее выходит инвалид, искалеченный и физически, и морально. Физически— потому что не сбросишь со счетов многочисленные вывихи, переломы, сотрясения мозга. Морально — потому, что, привыкший жить среди всеобщего внимания и почитания, человек не может уже снизить уровень своего существования и после ухода из большого спорта чувствует себя никому не нужным.

«Если бы мы начинали заниматься спортом в 16— 18 лет, когда человек уже сознательно может выбирать свой путь, а в 9— 10 лет мы ничего вокруг не видим, кроме спорта, интерес к которому так искусно разжигается. Нам кажется, что это какой-то особый мир. Мы еще не знаем, как узко это трехмерное пространство— зал, дом, сборы. И даже при том, что спортсмены так много ездят, видят, духовно они страшно обделены. Нагрузки, нагрузки, нагрузки. Ничего не существует, кроме нагрузок, которые постоянно растут, и кажется порой, что все, сил больше нет. Но тренер мне сказал однажды: «Пока ты не сломаешься, тебя никто не отпустит».

Я настолько привыкла себя преодолевать— не хочется, страшно, нельзя есть, нельзя пить,— что в первые годы после травмы, когда я только лежала, мне было дико, что от меня ничего не требуется. Мне так нужно было это чувство хоть какого-то преодоления, что я начала голодать, просто так. Мучить себя. Привычка…»

Я часто вспоминаю один эпизод из жизни нашей прославленной олимпийской чемпионки по фигурному катанию Ирины Родниной. Помните, когда она упала на тренировке с поддержки, ударилась головой об лед, ее отвезли в больницу с сильным сотрясением мозга, а через несколько дней все с тем же сотрясением мозга она выступала в соревнованиях и выиграла, наша маленькая мужественная женщина Роднина. Во славу ее мужества тогда было написано немало газетных материалов, снято телефильмов, даже написано книг. Но я снова и снова задаю себе вопрос: ради чего надо было заставлять ее в полубессознательном состоянии выходить тогда на лед? И если она сделала это по доброй воле, то кто загипнотизировал ее мыслью, что «за нами Москва», что «отступать некуда»? Ведь не война же! Спорт — благородное дело!

«Есть такие понятия— честь клуба, честь команды, честь сборной, честь флага. Слова, за которыми не разглядеть человека. Я никого не осуждаю и никого не виню в том, что со мной случилось. Ни Клименко, ни тем более тогдашнего тренера сборной Шанияздва. Клименко мне жалко— он жертва системы, член клана взрослых дядей, которые делают «дело». Шанияздова я просто не уважаю. А другие? Я травмировалась, потому что все вокруг меня соблюдали нейтралитет, отмалчивались. Видели ведь, что я не готова к исполнению этого элемента. Но молчали. Никто не остановил человека, который, все забыв, рвал вперед— давай! давай! давай!».

Нельзя сказать, что нынешние перемены, происходящие в нашей жизни, не затронули спорт, скажем, и спортивную гимнастику. Например, ее руководители решили, что отныне она будет более зрелищной и более женственной. То есть наконец мы на помосте увидим не девочек детсадовского телосложения, а… Об этом со всей ответственностью заявил на пресс-конференции, посвященной открытию очередного турнира «Московские новости», начальник управления гимнастики Госкомспорта СССР Леонид Аркаев. И с гордостью назвал фамилии гимнасток, которых мы видим на помосте уже не первый год и которые, несмотря на возраст, не в обиду им будет сказано, пока еще мало напоминают женщин. И еще он сказал на той пресс-конференции, что сейчас в современной спортивной гимнастике нет ни одного спортсмена, который выступает на мировом уровне и который не был бы травмирован. Он, правда, добавил, что это не для печати (надо же придумать: на пресс-конференции — не для печати!). Мы послушно закивали головами. Но я все-таки позволила себе привести это откровение, потому что, во-первых, время такое, а во-вторых, потому что уверена: на карьере Аркаева это никоим образом не отразится. Кого интересуют травмы, когда наша гимнастика в авангарде мирового спорта? Против лома, как говорится, нет приема.

Придирчивый читатель, возможно, возразит мне: ведь и на Западе, за рубежом спортсмены поставлены в такие же условия, им тоже приходится рисковать и жертвовать своим здоровьем. Да, вынуждена согласиться. Но есть одно маленькое «но». Там, «у них», атлеты делают это во имя баснословных денег, во имя обеспеченного будущего — своего и своей семьи. У нас так долго морочили людям голову липовым любительством отечественного спорта, что и вовсе было не понятно: ради чего? Ради того, чтобы госкомспортовские функционеры могли гордо отрапортовать…

Я далека от мысли, чтобы обвинить во всех грехах спорт — прекрасное и благородное изобретение человечества. Более того, одним из основных завоеваний новой социально-экономической системы был именно спорт, массовый, доступный всем и каждому. Но постепенно, как, впрочем, и многие другие области нашей жизни, спорт перекочевал из каждодневности на площади первомайских парадов и на пленки жизнерадостных кинофильмов. Утвердилась фальшивая массовость. Дутые цифры физкультурников, мертвый комплекс ГТО, который тщетно пытаются реанимировать, развалившиеся стадионы, отсутствие хоть какой-то спортивной одежды. А на фоне этого — блистательные победы, взмывающие флаги и слезы в глазах победителей.

«Наставникам, хранившим юность нашу…» Спорт— удел молодых. Но за ним стоят вполне взрослые люди, играющие во вполне взрослые игры. Им надо менять свое отношение к спорту. Или их надо менять. Ведь судьба Елены Мухиной — лишь вершина огромного айсберга искалеченных судеб. Задумаемся над этим.

Оксана ПОЛОНСКАЯ

Фото Анатолия БОЧИНИНА.

Many thanks to Allison for helping me track down this article.

Appendix: How a Swiss Newspaper Covered the Interview

As we’ve seen in the last two posts, news about Mukhina was followed closely. Her first interview after the accident was no exception. Instead of offering a straight translation of the Ogonyok piece, Bachkatov’s article leaned toward dramatization, taking poetic license and even putting words in her mouth. At one point, the newspaper quotes her saying, “I wanted to die,” when the original phrasing was more distant: “She desperately wanted to die” (Очень хотелось умереть). Here’s how the Swiss paper reported it…

Elena Mukhina, Former Soviet Gymnast, Speaks Eight Years Later

A Factory for Destroying Athletes

From Moscow, N. Bachkatov

Eight years later, the magazine Ogonyok has found Elena Mukhina, a former child prodigy of Soviet gymnastics. In a wheelchair, in the depths of a suburb, in a modest two-room apartment, with only the grandmother who had taken her in as an orphan at age 5 as her companion.

Just weeks before the opening of the Olympic Games, the magazine uses her case to deliver a virulent indictment against “the inhumanity of competitive sport,” particularly the subordination of medicine to coaches’ demands and their contempt for the moral or physical health of young children.

Broken Vertebrae

On July 3, 1980, two weeks before the opening of the Moscow Olympic Games where she was supposed to be one of the stars, Elena was training in the gym of her club in Minsk.* She had been forced to perform a new element involving a somersault that she had been struggling with since a foot fracture. She had protested having to go from the hospital to the training gym, with the only result being a follow-up X-ray followed by immediate surgery. The next day, according to her account, her coach subjected her to punishment by forcing her to train. “Fool that I was, I wanted to prove myself trustworthy, to be a hero.”

[Note: Mukhina’s gym was CSKA Moscow. The gymnasts were in Minsk, preparing for the Olympics.]

And on July 3, physically and mentally exhausted, Elena obeyed orders, fell several times, the last of which—a landing on her chin—broke her first vertebrae. Her morale was so low that her first thought was, “Thank God, I won’t go to the Games.”

While newspapers gave an idyllic version of her attitude during that famous training session—”she was suffering greatly but wanted to continue”—Elena remembers other feelings. “I wanted to die. Those first years when I was lying down all the time, I refused my fate, I didn’t want to drink or eat.”

Merciless Coaches

Eight years later, she breaks her silence on the condition of talking about sport and not about herself. And she describes this “terrible factory for manufacturing champions that, instead of forming healthy adults, destroys young children and rejects moral or physical invalids.”

“If we started intensive training at 16-18 years old, when the individual is capable of choosing their path, it would be different. But at 9-10 years old, we know nothing else in life but sport, the training gym. It seems like a world unto itself to us.”

She speaks of merciless coaches, determined to extract the maximum from their young students: “My coach had previously worked with a men’s team. He never made a distinction. Do you know when I was really scared: when I saw my performances on a TV screen again.” She also mentions the cowardice of those around her: “Everyone around us could clearly see that I wasn’t in condition to perform this element, but they kept quiet.” The obsession with medals “for the honor of the club, the honor of the team, the honor of the country,” the policy of silence, and the emptiness around her after the accident: “I received letters, often stupid ones, asking when I would return to the podium. Obviously, these people weren’t guilty—they had been lied to because it was clear from the beginning that I would never lead a normal life again.”

Necessary Injuries…

While some progress has been made since then (a return to more feminine gymnastics, with young girls rather than little kids), serious risks are still considered a normal tribute to pay for victories. At a recent press conference, Leonid Arkayev, head of the USSR Sports Committee’s Gymnastics Department, calmly declared that “under current competition conditions, no athlete reaches international level without injuries.”

“Fair enough in the West,” estimates the Ogonyok journalist, since gymnasts take these risks for money or to secure their future. But in the East, where these criteria don’t apply, why do gymnasts take these risks? To secure the bright future of the sports committee? To guarantee a bullfight spectacle where the athlete becomes the bull? To serve their country as if athletes were soldiers? Is our country’s honor worth this price?

In fact, this raises a problem recently discussed in several Soviet newspapers: the respective places of mass sport and competitive sport. “While one of the Soviet Union’s great prides is having popularized sports practice, how did we pervert this goal to emphasize high-level competitive sport?”

Cruel Juxtaposition

But never had criticism been pushed so far. Never had an article found a more cruel illustration than the juxtaposition of two photos: one of a very young gymnast balanced on the beam, the other of a young girl with a sad face in a wheelchair. Elena Mukhina, former Soviet gymnast.

La Liberté, August 2, 1988

Elena Moukhina, ex-gymnaste soviétique , parie huit ans après

Une usine à démolir les sportifs

De Moscu, N. Bachkatov

Huit ans après, la revue « Ogoniok » a retrouvé Elena Moukhina, une ancienne enfant prodige de la gymnastique soviétique. Dans un fauteuil roulant, au fond d’une banlieue, dans un modeste appartement de deux pièces, avec pour seule compagne la grand-mère qui l’avait recueillie orpheline à l’âge de 5 ans.

À quelques semaines de l’ouverture des Jeux olympiques, la revue utilise son cas pour se livrer à un virulent réquisitoire contre « l’inhumanité du sport de compétition », notamment la soumission de la médecine aux exigences des entraîneurs et le mépris de ces derniers pour la santé morale ou physique de jeunes enfants.

Vertèbres brisées

Le 3 juillet 1980, deux semaines avant l’ouverture des Jeux olympiques de Moscou dont elle devait être une des vedettes, Elena devait s’entraîner dans la salle de son club de Minsk. On lui avait imposé un nouvel élément comportant un salto qu’elle réalisait difficilement depuis une fracture du pied. Elle avait protesté alors de devoir passer de l’hôpital à la salle d’entraînement avec pour seul résultat une radiographie de contrôle suivie d’un passage immédiat sur la table d’opération. Le lendemain, son entraîneur l’astreignait, selon ses dires, à une punition en la poussant à s’entraîner. « Folle que j’étais, je voulais me montrer digne de confiance, être une héroïne ».

Et le 3 juillet, épuisée physiquement et moralement, Elena obéit aux ordres, chuta à plusieurs reprises dont la dernière, un atterrissage sur le menton, lui brise les premières vertèbres. Son moral était si bas que sa première pensée fut « Dieu merci, je n’irai pas aux Jeux ».

Tandis que les journaux donnent une version idyllique de son attitude lors de ce fameux entraînement, « elle souffrait beaucoup mais voulait continuer », Elena se rappelle d’autres sentiments. « Je voulais mourir. Ces premières années où j’étais allongée tout le temps, je refusais mon sort, je ne voulais ni boire ni manger ».

Entraîneurs impitoyables

Huit ans plus tard, elle sort de sa réserve à condition de parler du sport et non d’elle-même. Et elle décrit cet « terrible usine à fabriquer des champions qui, au lieu de former des adultes sains, démolit de jeunes enfants et rejette des invalides moraux ou physiques. »

« Si on commençait l’entraînement intensif à 16-18 ans, quand l’individu est capable de choisir sa voie, ce serait différent. Mais à 9-10 ans, nous ne connaissons rien d’autre dans la vie que le sport, la salle d’entraînement. Cela nous paraît un monde en soi ».

Elle évoque les entraîneurs impitoyables, attachés à tirer le maximum de leurs jeunes élèves : « Mon entraîneur s’était occupé avant d’une équipe masculine. Il n’a jamais fait la différence. Savez-vous quand j’ai vraiment eu peur : en revoyant mes prestations sur un écran ». Elle dit aussi la lâcheté de l’entourage : « Tous ceux qui nous entouraient avaient bien vu que je n’étais pas en condition pour réaliser cet élément, mais ils se sont tus ». L’obsession des médailles « pour l’honneur du club, l’honneur de l’équipe, l’honneur du pays », la politique du silence et le vide autour d’elle après l’accident : « Je recevais des lettres, souvent stupides, me demandant quand je reviendrais sur le podium. Évidemment, ces gens n’étaient pas coupables, on leur avait menti car il était clair dès le début que je ne mènerais plus jamais une vie normale ».

Blessures nécessaires…

Si quelques progrès ont été enregistrés depuis (retour vers une gymnastique plus féminine, avec des jeunes filles plutôt que des gamines), les risques graves restent considérés comme un tribut normal à payer pour les victoires. Lors d’une récente conférence de presse, Leonide Arkayev, chef du Département de gymnastique du comité des sports de l’URSS a déclaré paisiblement que « dans les conditions actuelles de compétition, aucun sportif n’attient le niveau international sans blessures ».

« D’accord à l’Ouest », estime le journaliste d’Ogoniok, puisque les gymnastes prennent ces risques pour de l’argent ou pour assurer leur avenir. Mais à l’Est, où ces critères n’ont pas cours, pourquoi les gymnastes prennent-ils ces risques ? Pour assurer l’avenir radieux du comité des sports ? Pour garantir un spectacle de corrida où le sportif devient le taureau ? Pour servir son pays comme si les sportifs étaient des soldats ? L’honneur de, notre pays est-il à ce prix ?

En fait, il soulève un problème récemment évoqué dans plusieurs journaux soviétiques, celui des places respectives du sport de masse et du sport de compétition. « Alors que l’une des grandes fiertés de l’Union soviétique est d’avoir popularisé la pratique sportive, comment a-t-on dévoyé ce but pour mettre l’accent sur le sport de grande compétition ».

Cruelle juxtaposition

Mais jamais on n’avait poussé si loin la critique. Jamais non plus un article n’avait trouvé plus cruelle illustration que la juxtaposition de deux photos : une d’une toute jeune gymnaste en équilibre sur la poutre, l’autre d’une jeune fille au visage triste dans un fauteuil roulant. Elena Moukhina, ex-gymnaste soviétique.