“Let’s do this without any sensationalism,” Elena Mukhina said in her 1989 interview with Sovetsky Sport. “I’m tired of sensationalism. I live like any other disabled person, and there’s nothing sensational in such a life.”

In the nine years that had passed since her accident—nine years since that summer when she was twenty and the Olympics opened without her—urban legends had grown like weeds: about the tumbling pass, about the coaches, about a miracle recovery. She knew them all, and she knew they weren’t true. “So much has been said,” she remarked.

The article that follows takes those urban legends one by one, stripping them down to their core. Legend One asks who was to blame: the coach who pushed too hard, the head coach who couldn’t stand his ground, or the gymnast herself, who had tried to speak but was not heard. It considers the diuretic that may have stripped calcium as ruthlessly as the system stripped agency, and the silence that followed. Legend Two turns to Valentin Dikul, the rehabilitation specialist whose name became shorthand for salvation, and to Mukhina’s refusal of treatment—born not of despair but of realism about her own body, already worn thin. Legend Three dismantles the rumor mill that insisted “Mukhina walks,” a myth that traveled across the globe.

What she offered instead of myth was testimony, calm and unsentimental. “You can’t trample over someone’s individuality for the sake of a medal,” she said. Her words came not as an indictment shouted from a podium but as the lived truth of someone who had already paid the price. In the wake of her injury, she described the sense of release: “Immediately, I felt freedom. Freedom from a coach’s dictatorship, freedom from everything. It was an extraordinary, almost joyful feeling.” That joy, however, was short-lived, and harsh realities followed. Yet out of that reckoning emerged a different kind of clarity. “I began to value human decency as a great gift,” she said. “Unfortunately, it is rare.”

What follows is a translation of her 1989 interview with Sovetsky Sport. Decades later, it remains as poignant as ever. As her interviewer, Natalia Kalugina, wrote in closing: “When I look at today’s champions, I think: God, may nothing happen to these girls! May their coaches hear them and understand them!”

Note: In my translation, I’ve preserved the bold typeface from the original publication.

Note #2: This is the final part in a four-part series. I’d urge you to first read part 1 (What the Soviet Union Printed about Mukhina’s Accident), part 2 (What the Rest of the World Printed about Mukhina’s Accident), and part 3 (Elena Mukhina Breaks Her Silence in “Grown-up Games”).

Elena Mukhina: Unknown Details

After Fame, After Tragedy

I didn’t see her in person — we spoke on the phone. That was her choice. Apparently, too many sensationalist reporters had descended on her in recent years. But later, when this piece was already written, we finally met, and we talked for a long time — about everything, about life, in general.

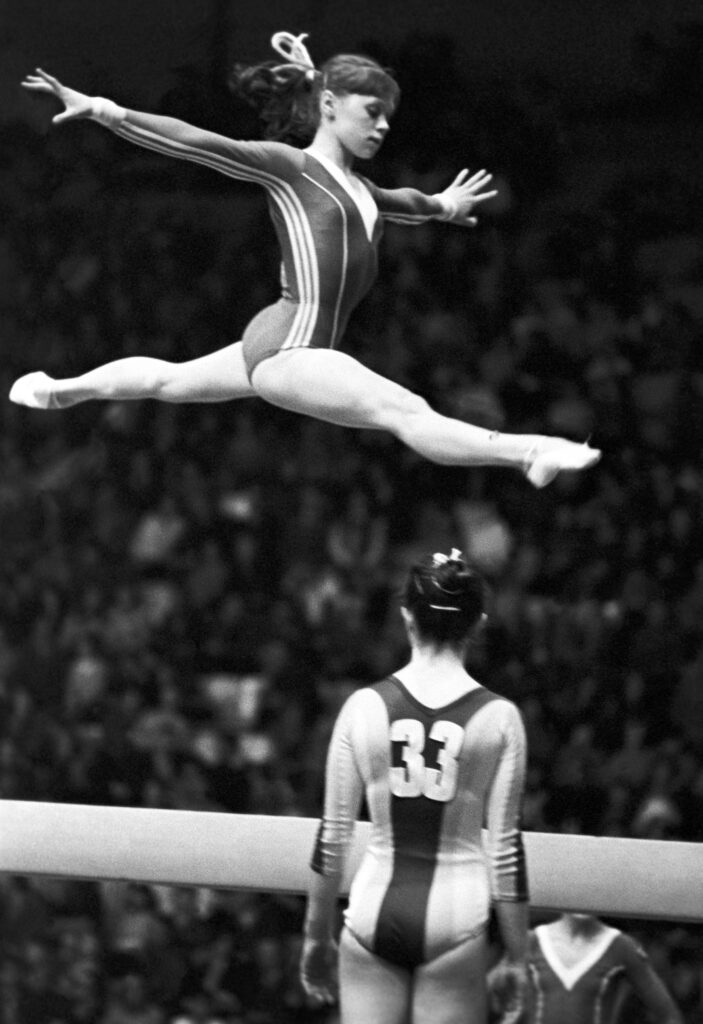

I remember her brilliant victory at the 1978 World Championships over the invincible Romanian Nadia Comăneci. I remember her beautiful “moon” salto,* as exquisite as Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. I remember the unique “Mukhina loop.” And it hurt terribly to see her immobile. Yet on the phone, first came a sweet, youthful voice, so much like those of her teammates Masha Filatova and Natasha Shaposhnikova.

[*Reminder: Moon salto was the name for a full-twisting double back at the time. Tsukahara’s high bar dismount was seen as a skill for the Space Age.]

— “Let’s do this without any sensationalism,” Lena asked of me. “I’m tired of sensationalism. I live like any other disabled person, and there’s nothing sensational in such a life.”

Indeed, the devastating injury Elena Mukhina suffered before the Moscow Olympics in 1980 so deeply shook us that, for the nine years that followed, we—perhaps feeling an unredeemable guilt before this fearless girl—dedicated ourselves to creating legends around her name. Legends sometimes inexplicable, and sometimes close to the truth. And perhaps the time has come to sort out what is true and what is not. After all, so many years have passed since that hot and carefree, that terrible summer day, when Moscow was preparing for a grand sporting celebration, and she, at just twenty years old, was dying on a neurosurgeon’s table.

Legend One. Who Is to Blame?

…Moscow was sweltering in the terrible heat. We, the interpreters working at the rowing course in Krylatskoye, had just come back from the Moskva River to our post, lazily wringing out our swimsuits and chatting merrily about something or other. Suddenly, flying up to us—there’s no other word for it—was the executive secretary of the rowing regatta: “Girls, the gymnasts in Minsk—something terrible has happened! Lena Mukhina has crashed. It looks like she’s dead. But they’ll be getting in touch with us. Just please, don’t say anything to the foreigners…” We stayed where we were, stunned. Conversation died down of its own accord…

…At my house, nine years later. Maria Filatova is speaking:

— “You know, Mukha* is the eternal wound of our team. She didn’t want to, she didn’t want to compete at the Olympics! She must have felt something terrible was coming. But her coach, Mikhail Klimenko, insisted—he even went to Moscow to ‘push through’ her inclusion on the team. Without him, everything happened. And she still, it seems, wasn’t in shape. Her leg hadn’t healed from the injury yet. That’s how it was.”

[*Mukha, which means “fly,” was her nickname.]

— “And I really didn’t want to make it onto the team.” — These are Elena Mukhina’s own words. — “And Klimenko knew it. My takeoff leg was injured; because of this, my routines were poorly prepared.”

— “But you were placed in the morning training group. In other words, you never made it into the main lineup.”

— “That’s why Klimenko left for Moscow. And I was left on my own. His wife looked after me, but she was a choreographer. The senior coach of the national team, Shaniyazov, kept coming around. But it didn’t do much good.

“The fact that they didn’t put me in the main lineup — I’m grateful for that. Training there is very difficult psychologically. At least this way, I spared my nerves.”

Opinion of a specialist who wished to remain anonymous: When they searched Mukhina’s bag, they found a strong diuretic — furosemide. As it turned out, she was “flushing out” weight instead of losing weight through acceptable means: running, diet, and a strict regimen. It leached calcium from her bones. Because of this, she couldn’t generate the speed needed to perform the element. The result was tragedy.

[Note: Furosemide was not a banned substance in 1980. It is a loop diuretic that increases calcium excretion in urine.]

— “I took furosemide. But that doesn’t mean much. If an element is prepared, well-polished, then at worst it might only cause a slight change in amplitude. But if a coach forces you to do an element that isn’t ready, as was the case with me, then, of course, anything can happen…”

Opinion of a teammate: “Who among us didn’t take ‘furo’? Officially, of course, the coaches knew nothing. But when at the evening weigh-in they tell you that by morning you need to ‘drop’ a kilogram or two, then problems arise about how this can be done in less than twelve hours. So we would take furosemide without the coaches knowing. But only Mukhina got injured. I don’t believe that ‘furo’ could have been the cause of the injury.”

Heavy silence on the line. And I catch my breath before the next question.

— “Lena, did you try to explain your condition to Klimenko?”

— “I tried, but what’s the use? Mikhail Yakovlevich is a superb technical coach. He can create a unique set of routines in two years. But when working on a set of routines, you can’t forget that you’re working with a person, not a robot. You can’t trample over someone’s individuality for the sake of a medal! But he doesn’t understand that. How many times did I try to talk to him, but he wouldn’t listen to me? More precisely, he didn’t want to listen. I’ll be honest — for me, getting along with him before the injury was very difficult. How it was for him — I don’t know. He might not have even noticed.”

— “And what about senior coach Aman Shaniyazov? In your conversation with Ogonyok you said that you ‘simply don’t respect him,’ but from other gymnasts I’ve only heard kind words about him.”

— “Shaniyazov could have saved me by insisting that I had no place on the Olympic team. But he didn’t know how to insist on anything. At that time, I had the impression that he wasn’t the team leader, but that any one of our personal coaches was. Ogonyok didn’t convey my words accurately. I don’t disrespect Shaniyazov as a person, but as a leader. He never did anything bad to me, but as a leader… You see, it’s terrible to realize: if only he had banged his fist on the table, if only he had crossed my name off the list of candidates with his own hand, I would be healthy now.”

— “So who is to blame, then?”

— “God only knows. Ask Klimenko — he will surely say I myself am to blame. You know, blame should not be divided. The past cannot be undone.”

Legend Two. Elena Mukhina and Valentin Dikul

[Note: Dikul is a famous rehabilitation specialist.]

Two years ago, I spoke with Olympic champion Natalia Kuchinskaya.

— “We need to go visit Mukhina. I feel like a pig for not going, but I can’t bring myself to. It’s frightening. But one thing I just don’t understand — why did she refuse to work with Dikul? He would have gotten her back on her feet. You can’t, you know, you just can’t shut yourself off in your grief like that! You have to look for a way out, you have to live. They offered her a real chance at salvation, and she turned it down. Why? I just can’t understand!”

— “Why did I refuse Dikul’s help? I had no idea about his system, but friends persuaded me to try. Well, then no sooner said than done. He came, took my measurements. Then they brought a machine for exercises. I began training. My kidneys were already weak, and his system provoked a flare-up. Though, God knows, maybe it was for the best. At least the doctors finally started paying attention to my kidneys. But it all ended with two serious operations and a six-month ban on any physical activity. Still, I went on training in secret. Then a relapse, another hospital stay. And so I had to start from zero again and again.

“Dikul would drop by from time to time, giving instructions. Then… then the muscle mass grew, and the discs in my spine started slipping out. In short, I decided that his system wasn’t for me. And one day I heard him on television, saying in effect that Mukhina was lazy and didn’t want to treat herself. Of course, he put it much more gently. This summer, by chance, I met Dikul in the hospital. I asked him why he had said that about me. After all, it wasn’t my fault that my health wouldn’t allow me to follow his instructions. And he said—that was his way of trying to lift my spirits.”

Legend Three. “Mukhina Walks!”

I now come to the hardest part of my story. In gymnastics, with all its conflicts, there was life, there was love. In the story with Dikul, there was a struggle for life. And what remains for her now, immobile, gravely ill? I wanted to ask her this question, but was afraid to do it. She herself steered away from the subject, preferring to reminisce about the past, and involuntarily returning to it. I asked her to answer all questions, no matter how harsh they might be, but I couldn’t bring myself to ask them. And yet, little by little, this topic began to emerge.

Usually, when asked how she lives, Lena answers: “Well.” And what else can she say to people who are casually interested in a nine-year-old tragedy? Start telling them about her problems? Why? They’ll feign a sigh and then run off to tell their acquaintances the next chapter of a half-forgotten tragedy.

But that “well” contains so much. She lives well in the sense that she did not die. She lives well in the sense that now she is hospitalized less often — her body has adapted. But the problems are countless. Even eating, raising a spoon to her mouth, is a problem.

— “And they said your hands move…”

— “Well, they move a little. I can bend at the elbow, but to straighten is hard. And my hands don’t work. And as for what they said… So much has been said. Once I read in a newspaper: ‘Mukhina walks.’ No, that is not in the cards for me. The doctors, physical therapy specialists, immobilized my joints and carried me around themselves. Journalists saw this sensation and wrote that I could walk.

“In spring, the local disability society called to ask how I was feeling. I answered honestly: not well. They were surprised.

“You know what shocked me about the world of disability? Envy. Relentless, dark, and vicious envy. How many times have I heard: “Look at her — Mukhina has it good, she gets so much!” (Since my injury was work-related, the district council pays 120 rubles, and the Sports Committee supplements that to the amount I was receiving on the national team. Plus, the same committee pays for utilities and medical services.) ‘She gets a dacha, a special bed, while we have nothing at all.’ What goes on in my soul doesn’t interest these so-called fellow sufferers. That’s why I prefer the company of healthy people. Otherwise, it’s too heavy.”

— “Do your teammates visit you?”

— “If they need to, they’ll visit. But it’s hard for them too. They live outside Moscow, with families and jobs. No, I see friends from outside the sport more often.”

— “And Klimenko?”

— “He calls, comes once a year to congratulate me on my birthday.”

— “Have you changed since the injury?”

— “Immediately, I felt freedom. Freedom from the coach’s dictates, freedom from everything. It was an extraordinary, almost joyful feeling. Then I was confronted with the realities of life. That says it all. Even with doctors, I didn’t always get along.

“But my view of people changed. I began to value human decency as a great gift. Unfortunately, it is rare.

“In general, now I treat everything calmly. That came only after I had struggled through many problems on my own, without anyone’s help.”

— “There were rumors that after graduating from the Institute of Physical Culture, you became a graduate student.”

— “They offered, but in a rather unobtrusive way. Professors would come to give me exams. They would leave somewhat moved and decide to help. I understood why the offer came up, and I also understood that once a person walked out of this apartment, they were plunged back into the usual rhythm of life. In the end, people forgot their promises, and I didn’t remind them. But really, I’d love to be coaching, to ‘spin the girls in my hands,’ to work with them!”

— “Lena, what about the future?”

— “If what I have in mind works out, then the future will be good. But don’t make me talk about it. So many of my undertakings have ended ingloriously that I am afraid to jinx it. I started learning languages and doing many other things, but illness always interrupted. So, goodbye for now, all right? If it works out, then I will tell you.”

Elena Mukhina is a symbol and eternal reproach to our artistic gymnastics. Who, in the end, was guilty of the misfortune that befell her? Perhaps, as she says, it is no longer important. Nine years ago, experts looked into it and concluded that it was an accident. But, still, when I look at today’s champions, I think: God, may nothing happen to these girls! May their coaches hear them and understand them!

A year after the Moscow Olympics, practically the entire women’s team of 1980 left the sport — they were so shaken by what happened to Mukhina. They left, never to return to the gym again. And yet they did return, as coaches and judges. And it was Elena Mukhina herself who brought them back. I remember the words of a bright, sensitive person from that team, gymnast Natalia Shaposhnikova: “My dear Mukha! With your courage, with your life, you forced us, too, to become stronger…” And for this spirit, instilled in those girls by Lena from behind the hospital walls, we owe her immense thanks—and a deep, reverent bow.

N. Kalugina

Sovetsky Sport, September 30, 1989

Printed on the front page

Елена МУХИНА: неизвестные штрихи

ПОСЛЕ СЛАВЫ, ПОСЛЕ ТРАГЕДИИ

Я ее не видела — разговаривала по телефону. Это было ее решение — видимо, слишком много охотников за «желтинкой» за последние годы свалилось на ее голову. Но потом, когда этот материал был уже готов, мы все же встретились и долго говорили — обо всем. В общем, о жизни.

Я помню ее блистательную победу на чемпионате мира в 1978 году над непобедимой румынкой Надей Комэнечи, помню ее прекрасное, как «Лунная соната» Бетховена, «лунное» сальто, помню неповторимую «петлю Мухиной», и было очень больно видеть ее недвижимую. Но сначала в трубке раздался милый, молодой голос, напоминающий голоса ее подруг по сборной Маши Филатовой и Наташи Шапошниковой.

— Только давайте без сенсаций, — попросила меня Лена. — Я устала от сенсаций. Живу обычно, как и все инвалиды, и ничего сенсационного в такой жизни нет.

Действительно, тяжелейшая травма Елены Мухиной перед московской Олимпиадой-80 настолько потрясла нас, что все девять последующих лет мы, вероятно, чувствуя неискупимую вину перед этой бесстрашной девочкой, посвятили созданию легенд вокруг её имени. Легенд порой необъяснимых, а порой соответствующих истине. И, пожалуй, пришло время разобраться — что правда, что нет. Ведь столько лет прошло с того жаркого и беззаботного, того страшного летнего дня, когда Москва готовилась к грандиозному спортивному празднику, а она, двадцатилетняя, умирала на столе нейрохирурга.

ЛЕГЕНДА ПЕРВАЯ. Кто виноват?

…В Москве стояла страшная жара. Мы, переводчицы, работавшие на канале в Крылатском, только что вернулись с Москвы-реки к месту службы, лениво выжимали купальники и весело о чем-то болтали. Вдруг к нам подлетела, иного слова и не подберешь, ответственный секретарь соревнований гребцов-«академиков»: «Девочки, в Минске у гимнастов — беда! Разбилась Лена Мухина. Кажется, насмерть. Но они еще будут связываться с нами. Только, просьба, иностранцам ничего не говорить…». Мы остались, потрясенные, на местах. Разговоры стихли как-то сами собой…

…У меня дома девять лет спустя. Говорит Мария Филатова.

— Ты понимаешь, Муха — это вечная боль нашей команды. Не хотела она, не хотела выступать на Олимпиаде! Чувствовала, наверное, что происходит что-то страшное. А ее тренер Михаил Клименко настаивал, поехал даже в Москву «пробивать» ее в команду. Без него все и случилось. А она все-таки, похоже, была не в форме. Нога у нее после травмы еще не прошла. Вот так-то.

— А я, действительно, не хотела попадать в команду. — Это уже слова самой Елены Мухиной. — И Клименко знал об этом. Была травмирована толчковая нога, из-за этого программа оттренирована плохо.

— Но вас же поставили в утреннюю смену на тренировках. То есть, иными словами, вы в основной состав и не попадали.

— Поэтому-то Клименко и уехал в Москву. А я осталась одна. Присматривала за мной его жена, но она хореограф. Кругами ходил старший тренер сборной Шаниязов. Но толку от этого было мало.

А то, что не поставили в основной состав, вот за это спасибо. Тренироваться там очень тяжело морально. Так я хоть нервишки поберегла.

Мнение специалиста, пожелавшего остаться безымянным: Когда разбирали сумку Мухиной, то нашли там сильное мочегонное средство — фурасемид. Она, как оказалось, так вес «гнала» вместо того, чтобы снижать вес допустимыми средствами — кроссами, диетой, строгим режимом. Вывела кальций из костей. Из-за этого не смогла набрать темпа при исполнении элемента. В результате — трагедия.

— Пила я фурасемид. Но это еще мало что значит. Если элемент готов, хорошо “обкручен”, то это в худшем случае может привести лишь к небольшому изменению амплитуды. А если тренер заставляет тебя делать неготовый элемент,

как это было со мной, то тогда, конечно, может всякое случиться…

Мнение подруги по команде: А кто из нас не пил «фуру»? Официально, конечно, тренеры ничего не знали. Но когда на вечернем взвешивании тебе говорят, что к утру надо «скинуть» килограмм, другой, то тут возникают проблемы, как это можно сделать меньше, чем за двенадцать часов. Вот мы без тренеров и пили фурасемид. Но травмировалась-то одна Мухина. Не верю, что «фура» мог быть причиной травмы.

В трубке тяжелое молчание. А я перевожу дух перед следующим вопросом.

— Лена, а вы пробовали объяснить свое состояние Клименко?

— Пробовала, а что толку? Михаил Яковлевич — прекрасный технарь. Он за два года может поставить уникальную программу. Но ведь, работая над программой, нельзя забывать, что работаешь с человеком, а не с роботом. Нельзя переступать через личность во имя медали! А он этого не понимает. Сколько раз я пыталась с ним поговорить, а он меня не слышал. Точнее, не желал слышать. Честно скажу, для меня отношения с ним перед травмой были очень тяжелыми. Как для него — не знаю. Он мог этого и не почувствовать.

— А старший тренер Оман Шаниязов? В своем разговоре с «Огоньком» вы сказали, что вы его «элементарно не уважаете», а от других гимнасток я слышала о нем только добрые слова.

— Шаниязов мог меня спасти, настояв на том, что мне не место в олимпийской сборной. Но он ни на чём не умел настаивать. У меня в то время складывалось впечатление, что не он руководитель команды, а кто-то из наших личных тренеров. «Огонек» не точно передал мои слова. Я не уважаю Шаниязова не как человека, а как руководителя. Он мне ничего плохого не сделал, а как руководитель… Понимаете, страшно сознавать, что стукни он тогда кулаком по столу, вычеркни он тогда меня из списков кандидатов своей рукой, и я бы была здорова.

— Так кто всё-таки виноват в происшедшем?

— А бог его знает. Спросите вы Клименко, он наверняка скажет, что я сама виновата. Знаете, не надо делить вину. Прошлого не вернёшь.

ЛЕГЕНДА ВТОРАЯ. Елена Мухина и Валентин Дикуль.

Года два назад мне довелось разговаривать с олимпийской чемпионкой Натальей Кучинской.

— Надо к Мухиной съездить. Свиньей себя чувствую, а собраться не могу. Страшно. Но одного не пойму — почему она отказалась заниматься с Дикулем. Он бы ее на ноги поднял. Нельзя, понимаешь, нельзя так замыкаться на своем горе! Надо искать выход, надо жить. Ей же предложили реальное спасение, а она отказалась. Почему? Не могу понять!

— Почему я отказалась от помощи Дикуля? Я о его системе представления не имела, но друзья уговорили попробовать. Что ж, сказано — сделано. Он пришёл ко мне, снял параметры. Потом привезли станок для занятий. Начала работать. У меня и без того были слабые почки, а его система спровоцировала обострение. Хотя, бог его знает, может, это и к лучшему. По крайней мере, врачи хоть занялись моими почками. Но всё кончилось двумя тяжёлыми операциями и запретом на полгода на любые физические нагрузки. Но я всё равно занималась втихаря. Потом срыв, больница. И так не раз приходилось всё начинать с нуля. Периодически заходил Дикуль, давал указания. Потом… Потом разрослась мышечная масса, стали вылетать диски позвонков. В общем, я решила, что мне его система не подходит. А как-то раз услышала по телевизору его слова, смысл которых заключался в том, что Мухина — лентяйка и сама не хочет лечиться. Хотя сказано всё было, конечно, намного мягче. В этом году летом случайно встретила Дикуля в больнице, спросила, за что он меня так. Ведь я не виновата в том, что здоровье не позволяет следовать его наставлениям. А он мне — это, говорит, я твой моральный дух хотел поднять таким образом.

ЛЕГЕНДА ТРЕТЬЯ. «Мухина ходит!»

Я приступаю к самой тяжелой части своего рассказа. В гимнастике, со всеми ее конфликтами, была жизнь, была любовь. В истории с Валентином Дикулем была борьба за жизнь. А что осталось ей сейчас, недвижимой, тяжело больной? Я порывалась задать ей этот вопрос и боялась сделать это. Она сама уходила от разговора, охотнее вспоминала прошлое, и невольно возвращалась к нему. Я ее просила отвечать на все вопросы, какими бы жесткими они ни были, и не

могла задавать их. И все же постепенно, ощупью, вырисовывалась и эта тема.

Обычно на вопрос, как она живет, Лена отвечает: «Хорошо». Да и что она может сказать людям, праздно интересующимся историей девятилетней давности? Начать рассказывать о своих проблемах? Зачем? Те ведь притворно повздыхают и побегут рассказывать своим знакомым продолжение полузабытой трагедии.

А это «хорошо» столько в себе таит. Она живет хорошо по сравнению с тем, что могла умереть. Она хорошо живет потому, что в больницу сейчас попадает чуть реже, чем раньше — организм приспособился к болезни. А проблем — не счесть. Проблема даже поесть, донести ложку до рта.

— А говорили, что руки у вас двигаются…

— Ну как двигаются. Могу согнуть в локте — разогнуть трудно. А кисти не действуют. А что говорили… Так много чего говорили. Однажды в одной из газет прочла: Мухина ходит. Нет, этого мне не дано. Просто врачи, специалисты по лечебной физкультуре, фиксировали мне суставы и таскали на себе. А журналисты углядели в этом сенсацию и написали, будто я хожу.

Весной позвонили из районного общества инвалидов, поинтересовались, как я себя чувствую. Я им честно ответила, что неважно. Почему-то удивились.

Знаете, что меня потрясло в инвалидном мире? Зависть, беспробудная, черная, злая. Сколько раз слышала — ишь, этой Мухиной хорошо — много получает (мне, так как травма у меня производственная, райсобес платит 120 рублей, а Госкомспорт доплачивает до той суммы, которую я получала в сборной. Плюс тот же комитет оплачивает бытовые и медицинские услуги). Ей, видишь ли, Госкомспорт — дачку в Подмосковье, функциональную кровать и т. д. и т. п., а мы вообще ничего не имеем. То, что творится у меня на душе, этих якобы товарищей по несчастью не интересует. Поэтому стараюсь общаться со здоровыми людьми. Иначе — слишком тяжело.

— Подруги из сборной навещают?

— Понадоблюсь — навестят. А вообще им тоже непросто. Все немосквички, семьи, работа. Нет, у меня чаще бывают друзья не из спорта.

— А Клименко?

— Звонит, приезжает раз в год поздравить с днем рождения.

— Вы изменились после травмы?

— Сразу почувствовала свободу. Свободу от диктата тренера, свободу от всего. Было необычайное чувство почти радости. Потом столкнулась с жизненными реалиями. Этим все сказано. Ведь даже с некоторыми врачами отношения не сложились.

Правда, кардинально изменилось отношение к людям. Я стала ценить как великий дар человеческую порядочность. Она, к сожалению, так редко встречается.

Но в принципе сейчас стала ко всему относиться как-то спокойнее. Это произошло уже тогда, когда многие проблемы я преодолела одна, без чьей-либо помощи.

— Ходили слухи, что после окончания инфизкульта вы стали аспиранткой.

— Предлагали, но как-то ненавязчиво. Приходили преподаватели принимать у меня экзамены. Уходили под некоторым впечатлением, решив помочь. Я понимала, почему возникло это предложение, понимала и то, что, выходя из этой квартиры, человек окунался в привычный ритм жизни. В общем, люди забывали об обещаниях, а я не напоминала. А вообще, мне бы на тренерскую, девчонок в руках «покрутить», повозиться с ними!…

Кстати, вы замечаете, сколько раз вы начали вопрос со слова «говорят»? Видите, сколько слухов ходит, а правды еще никто не сказал.

— Лена, а что в будущем?

— Если у меня получится то, что я задумала, то будущее — хорошее. Только не заставляйте меня говорить об этом. Столько моих начинаний кончалось бесславно, что я боюсь сглазить. Я уже и языки начинала учить и многим другим заниматься, но все прерывала болезнь. Так что до свидания, ладно? Если получится, то тогда я все расскажу…

Елена Мухина — символ и вечный укор нашей спортивной гимнастике. Кто в конце концов виноват в постигшем ее несчастье, наверное, и она в этом права, сейчас не так уж и важно. Девять лет назад в этом разобрались специалисты и пришли к выводу — несчастный случай. Но почему-то я смотрю на сегодняшних чемпионок и думаю: господи, только бы с этими малышками ничего не случилось! Только бы услышали, почувствовали их тренеры!

Через год после московской Олимпиады практически вся женская гимнастическая сборная образца 1980 года простилась со спортом — настолько потрясло их то, что произошло с Мухиной. Ушли, чтобы никогда не возвращаться в зал. Но все-таки они вернулись, вернулись тренерами, судьями. И возвратила их все та же Елена Мухина. Я вспоминаю слова светлого, тонкого человека из той команды, гимнастки Натальи Шапошниковой: «Муха ты моя дорогая! Своим мужеством, своей жизнью заставила ты и нас стать сильнее…». И за это чувство, внушенное Леной девчонкам из-за больничной стены, спасибо ей великое и низкий земной поклон.

One reply on “1989: Elena Mukhina Addresses the Myths in “After Fame, after Tragedy””

Thank you for this series on Elena Mukhina. I’m glad to know the entire story – so sad and heartbreaking.