In this 1987 Sovetsky Sport reflection, Mikhail Voronin—Olympic champion, world champion, and one of the defining figures of Soviet gymnastics in the 1960s—turns his gaze backward. Now in his forties, serving as a coach and federation leader, Voronin considers not only the triumphs and frustrations of his athletic career but also the broader climate of the sport during his time. With the openness of perestroika reshaping public life, he frames his own story against questions of fairness, candor, and responsibility—whether in the judging halls of Mexico City in 1968 or in the meeting rooms of the Soviet gymnastics federation. His voice is that of an athlete who has lived through both glory and disillusionment, and who remains determined to draw meaning from them.

What emerges is not a simple memoir of victories and medals but a meditation on memory, injustice, and legacy. Voronin recalls the sting of controversial judging decisions, the joy of competing alongside legendary teammates and rivals, the slow pace of technical progress within the Soviet system, and the factionalism among coaches that weighed on athletes. Yet the piece also shows a man embracing the spirit of glasnost, learning from criticism, and measuring himself against ideals of loyalty and honor. At its core, Voronin’s account underscores the paradox he quotes from the philosopher Campanella: the more one understands, the more one realizes how much remains unknown. It is both a personal reckoning and a window into the shifting culture of Soviet sport on the eve of profound change.

Note: These interviews should be read against the backdrop of the sweeping cultural shifts taking place in the Soviet Union during the late 1980s. I’ll return to this context at the end of the post, since it is especially relevant to understanding Voronin’s reflections.

LESSONS OF LIFE.

A story about sport, written by famous champions

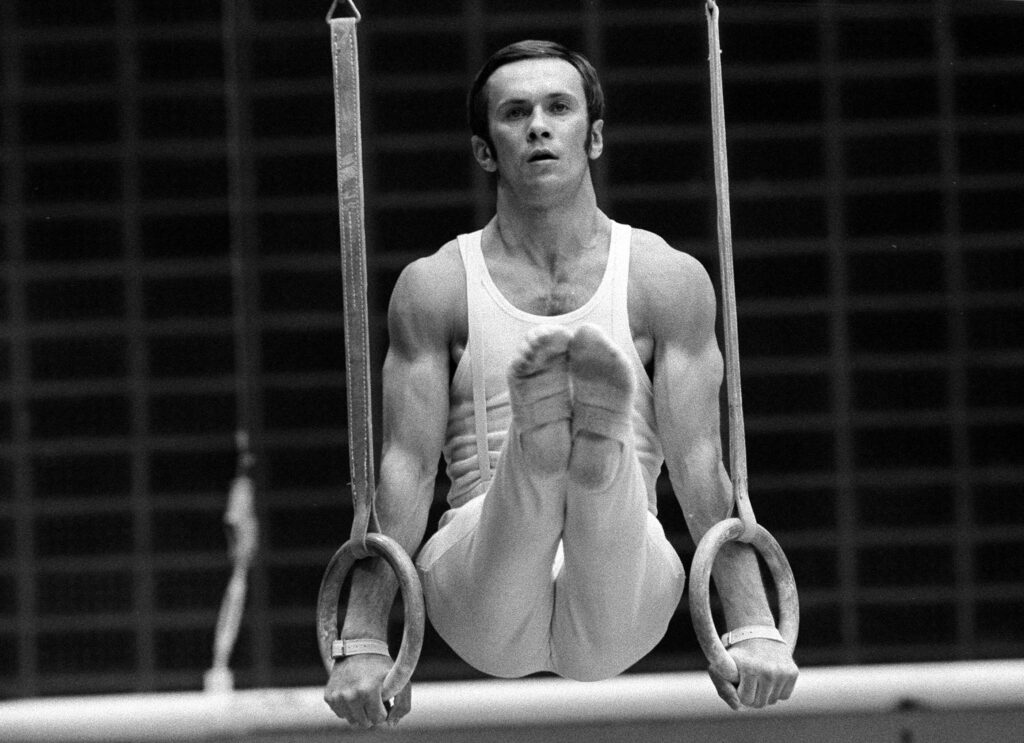

I close my eyes and imagine: I walk into the Dynamo gym, greet our coach Evgeny Viktorovich Korolkov, the guys, and finally approach Misha. “Well, if only he’d smile once, if only he’d crack a joke,” I think, as I look into his deep gray eyes. In them is he himself — Mikhail Voronin, not yet an Olympic champion; he will only become world all-around champion two years later. From his eyes radiate determination. Determination and sadness.

Now I understand that the image of Voronin for everyone took on a heroic-tragic shape. Never had we had such a magnificent gymnast, as they say, gifted by God (perhaps only now he can be compared with the unique talent of Dima Bilozerchev), who nonetheless had more defeats and life’s hardships than anyone else. He is 42, he has endured, he has persevered, and there is still determination in his eyes. And a touch of sadness. The whirlwinds of life have left their blurred traces of suffering on his steep forehead. He is still lean, fit, only his cheeks have sunken more deeply, and his brow ridges have become more prominent. The head coach of CS “Dynamo,” a lieutenant colonel, chairman of the Russian Gymnastics Federation. Gymnast. Coach. Leader. A man of perestroika. Our contemporary.

V. Golubev.

Mikhail Voronin: “The More I Have Understood…”

CHAPTER SIXTY-ONE

I recently read Vladimir Tendryakov’s An Assault on Mirages: “The past sits within us; it is our flesh and our spirit; without it, we do not exist—we are a distillation of the past.” That applies to us all, including me.

We love our past, whether it was sweet or troubling for us. You can’t forget it or erase it. Our life is like frozen music—bravura and intoxicating, sad and elegiac. It is simply essential to turn to the past, to examine it closely, peering at yellowing snapshots and reading the pages of old newspapers. We measure our present deeds against the past and ask ourselves: Are we living, acting, and planning for the future the right way?

Once upon a time, I dabbled in little verses, just for myself. I kept a diary—not just about sports—jotting down turns of phrase I liked and quotations from books. I could put something into rhyme. Before the 1966 World Championships, I woke up around two in the morning and scribbled: “Your hour has come: a leap, an effort—and you ascend the podium!” Silly, but it came true…

When people ask me what the hardest thing is in so-called elite sports—is it the training? the coach’s assignments? injuries and illness? the regimen?—I say no, none of that. The hardest thing is parting with sport, with the national team. Here are lines from my diary dated 1973: “But life goes on, and the clock strikes, and there is a wound in the heart—don’t go, don’t go! You step into a new world with fear and hope…”

How I would love to return to my youth! I was immensely proud to compete alongside such legends as Boris Shakhlin, Yuri Titov, Sergei Diomidov, and to vie on the podium with other giants of the world stage—Nakayama Akinori, Kasamatsu Shigeru, Kato Sawao, Kenmotsu Eizo, and Eberhard Gienger.

I would like to go back, just not to the year of the Mexico Olympics. That is a thorn in my heart, my painful memory. And although Boris Pasternak said that “yes, in life everything is dangerous,” I cannot watch the sports newsreels of those years without bitterness and pain. My dream was stolen from me! I claim this with full responsibility. How wonderful that now controversial moments can be resolved with the help of video replay. We figured out who was right and who was wrong in the Dnipro-Spartak soccer match. But back then, a monstrous injustice was committed in the Auditorio Nacional, and everyone got away with it.

I respect Kato Sawao as a gymnast. He is a two-time Olympic all-around champion, and his soft, catlike style of performance surely remained in the memory not only of me but of other connoisseurs of gymnastics. But at those Olympic Games in Mexico, he was not stronger than I was—I say that without boasting. We were going head to head, and I won’t hide the fact that my confidence grew stronger and stronger: I would not give up the victory for anything! When the audience is on your side and you feel your body ringing and springy, then the natural fear of an involuntary mistake disappears somewhere, and you go all out—you don’t tighten up… How dear to me are those memories of unadulterated happiness on the podium!

At that time, I feared only one thing: that the judges wouldn’t “waver,” that everything would be objective and fair. To be honest, I was stunned by what had happened at the [1964] Tokyo Olympics, where I went as an alternate. The Japanese gymnast Yukio Endo practically “rode” the pommel horse, yet he was given such a high score that everyone gasped. That allowed him to overtake his rivals. And Boris Shakhlin or Viktor Lisitsky could have won the all-around.

Alas, the situation repeated itself [in 1968]. On floor exercise, on the last event, Sawao Kato became so nervous and so flustered that he made so many clear, obvious mistakes that all my friends—and even my rivals from other teams—were already looking at me, beaming: Kato had lost! And suddenly—the stands began to howl; honestly, my eyes nearly popped out—Kato was given a 9.9. For what? I wanted to shout about the injustice. My breath caught in my throat; spasms tightened my throat. With that score, Sawao, wearing a guilty smile, edged me out by five hundredths of a point…

What did I feel at that moment? Better not to ask. I wanted complete solitude—no consolation and no condolences. My coach, Yevgeny Viktorovich Korolkov, was no less shocked than I was. Night. Mexico City. The Olympic Village. Noise in the street. Guitars. Songs. I lie there with my eyes open. I hate myself. Why? I don’t even know. I just wanted to fly home immediately, to Bashilovka. To hug my mother and pour my heart out to her. And to play “podkidnoy”* with my grandmother. So as not to think about anything. It seemed to me that in the morning all the newspapers would trumpet my defeat.

[*Note: Podkidnoy durak is a card game. Durak means “fool,” referring to the player who has all the cards at the end of the game.]

To my surprise, the press wasn’t stingy with praise for me, and the guys, on the whole, congratulated me. I shook off my stupor.

Were the two gold medals—for vault and horizontal bar—my consolation for losing the all-around title? In principle, yes. But the pain in my heart remained. Especially for our team.

Those were the times I had to compete in—when Japanese masters ruled the world stage, and we simply could not overtake them.

Of course, many watched the pop-music contest “Jūrmala-87”* this summer. And many surely wondered: we ought to have a huge number of talents, original singers, so where are they? There are very few true gifts—you could count them on the fingers of one hand. The rest imitate someone; others are bland and cut from the same cloth.

[*Note: The Jūrmala Young Pop Singer Competition was an annual competition held in Latvia from 1986 to 1993.]

It was the same with us then: we didn’t have an ensemble of soloists. And why? I am deeply convinced that our coaches and leaders kept saying we had to catch up with the Japanese—in difficulty, in elegance of execution. But the whole point is that this tactic is doomed to failure. Not to catch up, but to overtake—to look further ahead, not just to the next day.

Ljubljana was my second world championships (back then they were held once every four years), and as a two-time European and Olympic champion, I naturally burned to defend the top title I had earned in 1966. But then I had to say to myself with sorrow that my rivals had raced ahead, and Eizo Kenmotsu was phenomenal that day.

Now I understand the mistakes of those years (they were probably more coaching mistakes than the athletes’): routines were updated too slowly, and they were hindered by the wrong strategy. I, too, was learning new elements; I had come close to a triple twist; I was trying out an unusual vault; I was going to “make a revolution” on pommel horse. But at some point, the old stereotype kicked in—that, with the previous baggage, you could win through clean execution. It turned out you couldn’t!

During my time on the national team, my teammates and I more than once faced unpleasant psychological moments. For some reason, the coaches didn’t get along—they formed little cliques, which worried us greatly. Competition plans for major tournaments were discussed behind closed doors; the selection of candidates for the team was done in back rooms; much was done secretly; there was no talk of glasnost. Even at meetings of the All-Union Federation, some sharp questions about the preparation of the national team, its development prospects, and the selection of coaches were rejected on the pretext that public representatives didn’t need to be involved in all that.

You might ask how I knew this, since I wasn’t a federation member then. But believe me, an active athlete is concerned not only with training and whether there is chalk in the gym, but also with the “environment” in which he lives. Tell me, could I finish a workout normally if, in the middle of practice, the then-head of gymnastics—an esteemed man, though not a great specialist in our sport—showed up and severely scolded me, a world champion, for “doing my giants wrong” on rings and relaxing my knees (which is done on purpose, to feel the movement and technique)?

We feel the changes in our life today as keenly as the intoxicating spring air that makes the blood race. It turns out that many problems and omissions can be dispelled by glasnost and truthfulness. How much more interesting the meetings of the Presidium of the All-Union Federation have become! The senior coaches of the national teams openly share with us all their concerns, consult with us, and listen to the voice of the public. I wrote “all their concerns” and thought that I might have gone a little too far. No, not all yet—perhaps something is still left unsaid—but undoubtedly we are on the right path toward genuine candor and openness.

I, too, received a lesson in democracy. In the spring, we had a reporting-and-election plenum of the Gymnastics Federation of the Russian Federation, of which I am the chairman. To be honest, such plenums used to run by the book—quietly, peacefully. People spoke, they voted. This time, everything was different. A whole storm arose! With what passion and engagement those assembled spoke—how purposefully and with what arguments they criticized the federation’s sluggish work. It was as if people’s hands were unbound; thought began to flow; new ideas appeared. From this small example, you see clearly that no one wants to stay on the sidelines of perestroika!

I got my share of criticism, too. Honestly, both I and Viktor Ivanovich Borisov, head of the Department of Mass Sports of the RSFSR State Committee for Sport, were a bit taken aback: the criticism was very weighty. I even asked not to be elected for a new term. But in the course of the plenum, we were all convinced that only an honest conversation can help the cause. Problems were brought to light, tasks were set, and a work plan for the federation took shape. And yet people again placed their trust in me, electing me as chairman. It is pleasant, but it comes with a lot of responsibility.

…If someone asked me what important lessons I have taken from my forty-two years as an athlete, a coach, and head of Dynamo gymnastics, I wouldn’t hesitate. Replaying in my mind the sweetness of victories and defeats on the competition floor (believe me—there is a certain charm in failures: you come to know yourself), the monstrous anxieties of a coach (when I worked in the gym with Sasha Tkachev), the busy work at the Central Sports Club, I would answer clearly: “I have remained faithful to my native Dynamo. I began as a boy under Vitaly Alexandrovich Belyaev in the ‘Young Dynamo’ club, and to this day I have tied my life to the white-and-blue flag. I am proud that I am a Dynamo patriot, and all my thoughts and deeds are aimed at one thing: making Dynamo gymnasts famous throughout the world!”

…On August 26, my son Dmitry turned eighteen. And I didn’t even notice how he became completely grown up—taller than his father by a head. A Master of Sport in gymnastics, a second-year student at the Institute of Physical Culture. Most often, I talk to him about loyalty, about a citizen’s honor, which must be dearer than life. Once he asked me, “Dad, I understand that everything ends someday. But I know that a person always strives toward a goal. Have you achieved everything, Dad?”

I opened my diary and read to Dmitry from Tommaso Campanella, a dreamer and poet: “Desiring, feeling, I whirl within the circle of searching; the more I have understood, the more I do not know.” The understanding of life—for all of us—is endless!

Sovetsky Sport, September 6, 1987

УРОКИ ЖИЗНИ.

Повесть о спорте, написанная знаменитыми чемпионами

Вот закрою глаза и представляю: вхожу в динамовский зал, здороваюсь с нашим тренером Евгением Викторовичем Корольковым, с ребятами и подхожу, наконец, к Мише. «Ну, хоть бы улыбнулся разок, ну, хоть бы шутку отмочил», — думаю я и смотрю в его глубокие серые глаза. В них — он, Михаил Воронин, еще не олимпийский чемпион, а абсолютным чемпионом мира он будет только через два года. Из его глаз струится воля. Воля и печаль.

Это я теперь понимаю, что образ Воронина для всех сложился героически-трагически. Никогда у нас не было такого великолепного гимнаста, как говорится, судьбою божьей (разве вот только сейчас его можно сравнить с уникальным дарованием Димы Билозерчева), у которого все-таки поражений и жизненных неурядиц было больше, чем у кого-либо другого. Ему 42, он выстоял, выдюжил, в его глазах по-прежнему воля. И чуточку грусти. Вихри жизни оставили свои размытые страданием следы на его крутом лбу. Он так же худ, подтянут, только щеки ввалились поглубже, да надбровные дуги стали выпуклей. Главный тренер ЦС «Динамо», подполковник, председатель Федерации гимнастики России. Гимнаст. Тренер. Руководитель. Человек перестройки. Наш современник.

В. ГОЛУБЕВ.

ГЛАВА ШЕСТЬДЕСЯТ ПЕРВАЯ

Михаил Воронин: «Чем больше я постиг…»

Недавно прочитал у Владимира Тендрякова в «Покушении на миражи»: «Прошлое сидит в нас, оно наша плоть и наш дух, без него нас нет, мы — концентрат прошлого». Это обо всех нас, обо мне — тоже.

Мы любим свое прошлое, сладостное ли оно для нас было или тревожное. Его не забудешь, не вычеркнешь. Наша жизнь — как застывшая музыка, бравурная и пьянящая, грустная и элегическая. Пожалуй, просто необходимо обращаться в прошлое, разглядывать его пристально, всматриваясь и в пожелтевшие любительские снимки и вчитываясь в страницы стареньких газет. С прошлым мы сверяем свои нынешние дела, думаем, а так ли живем, действуем, планируем будущее?

Когда-то я баловался стишками, так, для себя. Вел дневник, не только спортивный, записывал понравившиеся выражения, цитаты из книг. Мог что-то зарифмовать. Перед чемпионатом мира-66 проснулся где-то часа в два ночи и начеркал: «Твой час настал: рывок, усилие — и ты восходишь на пьедестал!». Смешно, а сбылось…

Когда меня спрашивают, а что самое тяжелое в так называемом большом спорте? Тренировки? Задание тренера? Травмы, болезни? Режим? Нет, все не то. Самое тяжкое — прощание со спортом, со сборной. Вот и строчки из дневника, датированные 1973 годом: «Но жизнь идет, и бьют часы, и рана в сердце — не уходи, не уходи! Шагаешь в новый мир с опаской и надеждой…».

Как хотелось бы вернуться в свою юность! Я ведь неимоверно гордился, что выступал с такими знаменитостями, как Борис Шахлин, Юрий Титов, Сергей Диомидов, спорил на помосте и с другими грандами мирового помоста — с Акинори Накаямой, Сигеру Касамацу, Савао Като, Эйдзо Кенмоцу, Эберхардом Гингером.

Вернуться бы хотелось, только не в год мексиканской Олимпиады. Она — моя заноза в сердце, моя боль воспоминаний. И хотя Борис Пастернак сказал, что «Да, в жизни все опасно!», я не могу без горечи и боли смотреть на кадры спортивной хроники тех лет. У меня украли мою мечту! Берусь утверждать с полной ответственностью. Как хорошо, что сейчас можно спорные моменты решить с помощью видеозаписи. Вот разобрались же, кто прав, а кто виноват в футбольном матче «Днепр» — «Спартак». А тогда в зале «Аудиторио насьональ» была совершена чудовищная несправедливость, и все всем сошло с рук.

Я уважаю Савао Като как гимнаста. Он — двукратный абсолютный чемпион Олимпиад, и его мягкий, кошачий стиль исполнения наверняка запомнился не только мне, но и другим знатокам гимнастики. Но тогда в олимпийском Мехико он был не сильнее меня, это я утверждаю без бахвальства. Мы шли голова в голову, не скрою — во мне все крепла и крепла уверенность: победу не отдам ни за что! Когда зрители благоволят к тебе и ты чувствуешь свое звонкое, упругое тело, тогда естественный страх перед невольной ошибкой куда-то исчезает, и ты уже стараешься вовсю, не закрепощаешься… До чего же дороги мне эти воспоминания безраздельного счастья на помосте!

Тогда я боялся только одного: чтобы судьи не «дрогнули», чтобы все было объективно, честно. Признаться, я был ошарашен тем, что произошло на Олимпиаде в Токио, куда ездил запасным участником. Японец Юкио Эндо прямо-таки «оседлал» коня, а ему выставили такой высокий балл, что все ахнули. Это позволило ему обойти соперников. А ведь победить в многоборье могли и Борис Шахлин, и Виктор Лисицкий.

Увы, ситуация повторилась. Савао Като на вольных, в последнем виде, так занервничал, так засуетился, наделал так много явных, очевидных ошибок, что все мои друзья да и конкуренты из других команд уже смотрели на меня, расплываясь в улыбках, — Като проиграл! И вдруг — завыли трибуны, честно скажу, у меня глаза на лоб полезли — 9,9 дали Савао Като. За что? Хотелось кричать о несправедливости. Перехватило дыхание, спазмы сжали горло. С такой оценкой Савао с виноватой улыбкой обошел меня на пять сотых балла…

Что я испытывал в тот миг? Лучше не спрашивайте. Хотелось полного одиночества, никаких утешений и соболезнований. Мой тренер Евгений Викторович Корольков был шокирован не меньше меня. Ночь. Мехико, Олимпийская деревня. Шум на улице. Гитары. Песни. Лежу. С открытыми глазами. Ненавижу себя. За что? Сам не знаю. Только хочется немедленно улететь домой, на Башиловку. Обнять маму, поплакаться ей. И сыграть с бабушкой в «подкидного». Чтобы ни о чем не думать. Мне казалось, что все газеты утром будут вещать о моем проигрыше.

К моему удивлению, пресса не скупилась на похвалу в мой адрес, да в общем и ребята поздравляли. Я сбросил оцепенение.

Две золотые медали за опорный прыжок и упражнение на перекладине — это было утешением мне за потерю абсолютного титула? В принципе да. Но боль в сердце осталась. И особенно за нашу команду.

Вот в такие времена мне довелось выступать — когда на мировом помосте властвовали японские мастера, и обойти мы их никак не могли.

Конечно, многие смотрели этим летом эстрадный конкурс «Юрмала-87». И многие наверняка удивлялись — у нас вроде должно быть огромное количество талантов, самобытных певцов, а где они? Настоящих дарований — совсем немного, раз-два и обчелся. Остальные кого-то копируют, другие невыразительны, подстрижены под одну гребенку.

Вот и у нас тогда не было ансамбля солистов. А все почему? Я глубоко убежден, что наши тренеры, руководители все время говорили о том, что нам надо догнать японцев — по сложности, по изяществу исполнения. Но все дело в том, что эта тактика обречена на поражение. Не догнать, а перегнать, глядеть дальше, не только в ближайший день.

Любляна была моим вторым мировым первенством (тогда они проходили раз в четыре года), и мне, еще и двукратному чемпиону Европы и Олимпийских игр, конечно же, страстно хотелось отстоять высший титул, полученный в 1966 году. Но тогда я горестно сказал самому себе, что экспресс соперников умчался вперед, и Эйдзо Кенмоцу сегодня потрясающе хорош.

Теперь я понимаю ошибки тех лет (они, вероятно, больше тренерские, чем спортсменов): обновление композиций проходило слишком медленно, да и тормозилось неправильной тактикой. Ведь и я разучивал новые элементы, и к тройному «винту» вплотную подошел, и к необычному опорному прыжку примерялся, и на коне собирался «сделать революцию», но в какой-то момент сработал старый стереотип — с прежним багажом можно выиграть за счет чистоты исполнения. Оказалось — нельзя!

Во время своего пребывания в сборной страны я и мои товарищи не раз испытывали неприятные моменты психологического характера. Почему-то недружно жили тренеры, образовавшие как бы группировки, и нас это очень волновало. Планы выступлений на крупных турнирах обсуждались кулуарно, кандидатов в команду тоже выбирали за закрытыми дверями, многое делалось келейно, ни о какой гласности не было и речи. Даже на заседаниях Всесоюзной федерации некоторые острые вопросы подготовки сборной, перспективы ее развития, подбора тренеров в команду отклонялись под предлогом того, что общественникам совсем не обязательно во всем этом участвовать.

Меня могут спросить, а откуда я об этом знаю, ведь сам же не был тогда членом федерации? Но, поверьте, действующего спортсмена волнуют не только тренировки и есть ли магнезия в зале, но и «окружающая среда», в которой он живет. Скажите, мог ли я нормально завершить занятия, если в середине тренировки пришедший на нее тогдашний руководитель гимнастики (уважаемый человек, однако не очень большой специалист в нашем виде) строго выговаривал мне, чемпиону мира, что я неправильно выполняю большие обороты на кольцах да еще при этом расслабляю коленки (а это делается специально, чтобы почувствовать движение, технику)?

Перемены в нашей жизни мы ощущаем сегодня так же остро, как пьянящее, волнующее кровь дыхание весны. Сколько, оказывается, проблем, недомолвок можно снять гласностью, правдивостью. Насколько интереснее стали заседания президиума Всесоюзной федерации! Старшие тренеры сборных команд откровенно делятся с нами всем наболевшим, советуются, прислушиваются к голосу общественников. Вот написал «всем наболевшим» и подумал, что немного «перегнул палку». Нет, еще не всем, еще, может, что-то умалчивают, но, безусловно, мы все на верном пути к настоящей откровенности и гласности.

Урок демократии получил и я. Весной у нас был отчетно-выборный пленум федерации гимнастики Российской Федерации, председателем которой я являюсь. Что греха таить, подобные пленумы раньше проходили по сценарию, тихо, мирно. Поговорили, проголосовали. Нынче же все было по-иному. Поднялась целая буря! С какой страстью, заинтересованностью выступали собравшиеся, как целенаправленно, аргументированно критиковали вялую работу федерации. У людей как будто развязались руки, забила мысль, появились свежие идеи. На маленьком примере ясно видишь, что никто не хочет остаться в стороне от перестройки!

Досталось на орехи и мне. Честно скажу, что и я, и начальник Управления массовых видов спорта Госкомспорта РСФСР Виктор Иванович Борисов немного растерялись: уж очень полновесной была критика. Я даже попросил не избирать меня на новый срок. Но в ходе пленума мы все убедились, что только честный разговор и может помочь делу. Открылись проблемы, ставились задачи, наметился план работы федерации. И все же люди снова оказали мне доверие, выбрав председателем. Приятно, но ко многому обязывает.

…Если бы меня спросили, а что ты вынес важного из своей 42-летней жизни спортсмена, тренера, руководителя гимнастики «Динамо»? Я бы не задумался, и, прокрутив в памяти сладость побед и поражений на помосте (точно вам говорю — в неудачах есть своя прелесть познания самого себя), чудовищные тренерские волнения (когда несколько лет работал в зале с Сашей Ткачевым), хлопотную работу в ЦС, четко бы ответил: «Я остался верен своему родному „Динамо“. Как начинал мальчишкой у Виталия Александровича Беляева в „Юном динамовце“, так и по сей день жизнь свою связал с бело-голубым флагом. Горжусь, что я патриот-динамовец, и все думы и дела связаны с одним: чтобы гремели на весь мир динамовские гимнасты!»

…26 августа сыну Дмитрию исполнилось 18. И не заметил, как он стал совсем взрослым, выше отца на голову. Мастер спорта по гимнастике, студент второго курса института физкультуры. Чаще всего ему я говорю о верности, о чести гражданина, которая должна быть дороже жизни. Как-то он у меня спросил: «Пап, я понимаю, что все когда-нибудь кончится. Но я знаю, что человек всегда стремится к цели. Вот ты всего достиг, пап?».

Я открыл свой дневник и прочитал Дмитрию из Фомы Кампанеллы, мечтателя и поэта: «Желая, чувствуя, кружусь в кругу исканья, чем больше я постиг, тем большего не знаю». Постижение жизни для всех нас — бесконечно!

«…Так получилось, что в моей судьбе тесно переплелись театр, эстрада, кино, радио, телевидение… А спорт? С первых шагов мы шли с ним рука об руку, сейчас идем и будем идти. Потому что без спорта нельзя». Как вы, наверное, догадались, автор следующего «Урока жизни» — Николай Николаевич Озеров.

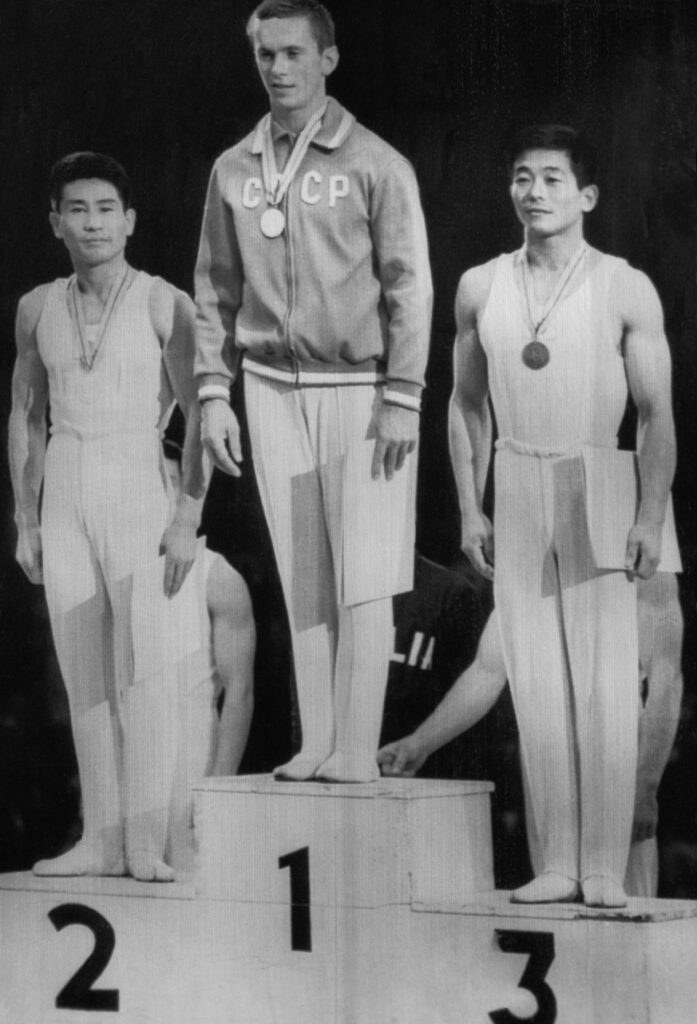

Dortmund. The world competitions in gymnastics. Mikhail Voronin (first place, UDSSR, C), Tsurumi (second place, Japan) and Nakayama (third place, Japan).

Appendix: A Brief Note on Glasnost and Sports in the USSR

Here’s a quick refresher of the basic timeline:

- In 1980, Moscow hosts the Olympic Games.

- In 1982, the Soviet President at the time, Leonid Brezhnev, died.

- In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev came to power with radically new policies of perestroika (restructuring the political and economic system) and glasnost (openness).

With that in mind, here’s a brief overview of the intersection of glasnost and Soviet sports in the late 1980s.

The 1980 Olympics in Moscow put a wedge between the sporting elite and the rest of the society.

To many people in eastern and central Europe and the USSR, however, the Olympic attainments and the Moscow Olympics diverted attention from the realities of living under communism. The Olympics illuminated the gap between elite sport and the rest of society, the manipulation of sport for political ends and the profligacy of pouring funds into a sporting spectacle for propaganda purposes when the economy had run out of steam and, in the case of the Soviet Union, was teetering on the brink of bankruptcy (partly as a result of US President Reagan’s policy of “squeezing til the pips squeak” in terms of the arms race).

James Riordan, “Sport after the Cold War: Implications for Russia and Eastern Europe”

After Gorbachev came to power and ushered in an era of glasnost, Soviet sports legends began to speak about their experiences. (This included the Elena Mukhina interviews in 1988 and 1989.)

In 1985, Party chief Mikhail Gorbachov had the task of saving a political system whose centre was experiencing dissolution, inevitably strengthening the centrifugal forces and making the system’s break-up inevitable — and with it the last remaining major world empire (the old Russian empire, with the cardinal exceptions of Poland and Finland, came under the rubric of the USSR after the 1917 Russian Revolution).

It was particularly in the field of sport, more rapidly than anywhere else —perhaps because of its popular nature — that the new era of glasnost (from 1985) exposed to public scrutiny the realities of the old system. Victims of repression began to publish their memoirs. Not just any old victims, but former sports stars whom the public had idolised. To take just one example, Nikolai Starostin had captained his country at both football and ice hockey, helped to found the Spartak Sports Society in the late 1930s, and managed the Soviet national football team.

He also spent ten years in Stanlin’s labour camps. […]

James Riordan, “Sport after the Cold War: Implications for Russia and Eastern Europe”

The truth slowly came out. Soviet sports were intertwined with the security services and fueled by state stipends, political control, and systematic doping. A few years later, leaders admitted the glossy participation numbers were a sham—only a tiny fraction of citizens actually exercised regularly.

What no one could say openly before, including during the 1980 Olympics, owing to strict censorship, was that Dinamo was the sports club sponsored and financed by the security forces, that athletes (Master of Sport ranking and above) devoted themselves full-time to sport and were paid accordingly, that athletes received bonuses for winning (including scarce dollars), that the Soviet NOC was a government-run institution and that its chairman had to be a member of the Communist Party, that the Soviet state manufactured, tested and administered performance-enhancing drugs to its athletes (while condemning bourgeois states for encouraging drug-taking).

Down the years, the Soviet leadership had produced regiments of statistics to show that millions were regular, active participants in sport; that the vast majority of school- and college-students gained a national fitness badge (the GTO – Gotov k trudeau i oborne — Prepared for Labour and Defence, originally based on Baden-Powell’s athlete’s badge); that rising millions (a third of the population!) took part in the quadrennial spartakiads; and that the bulk of workers did their daily dozen — “production gymnastics” — at the workplace.

Just a few years after the Moscow Olympics, however, the new leaders declared that these figures were fraudulent, a show to impress people above and below, and to meet preset targets. It was now admitted that no more than eight percent of men and two percent of women engaged in sport regularly.

James Riordan, “Sport after the Cold War: Implications for Russia and Eastern Europe”

As the Soviet economy crumbled, people began to see elite sport as a hollow spectacle—lavished with money, medals, and political fanfare while citizens queued for housing, phones, and cars. What had once been celebrated as national pride now looked like false glory, a fetish of trophies masking decay.

Once people started to see journalists writing about the past (under the slogan: “a nation that does not know its past has no future!”) and exposing the realities of elite sport, they started to question the very morality of sport, the price that society should pay for talent. Many expressed their unhappiness at what they saw as a race for false glory, the cultivation of irrational loyalties, the unreasonable prominence given to the winning of victories, the setting of records and the collecting of trophies — an obsessive fetishism of sport. This was, incidentally, the very criticism made of “sport” by strong opposition groups in the 1920s, particularly the “Hygienists” and the “Proletarian Culture” group.

This is, of course, an issue not unknown in other societies, especially those of scarcity. But for a population who had been waiting for housing, phones, and cars, who saw their economy collapsing, and who felt that sporting victories were being attained for political values they did not share — that is, that sports “heroes” were not their heroes — they were somehow accomplices in gilding the lily of the Communist Party — the vast sums being lavished on ensuring a Grand Olympic Show represented the straw that broke the camel’s back.

To many the worst aspect of the old system was misplaced priorities, the gap between living standards and ordinary sports and recreation facilities, on the one hand, and the money spent on elite sport and stars, on the other. As a sports commentator put it a year after the Berlin Wall came down and a year before the Soviet edifice tumbled, we won Olympic medals while being a “land of clapped-out motor cars, evergreen tomatoes and totalitarian mendacity.” Valuable resources were used to buy foreign sports equipment and pay dollar bonuses to athletes who won Olympic medals. For a gold medal at the Seoul Olympics of 1988, for example, Soviet recipients gained as much as 12,000 rubles (6,000 for silver and 4,000 for bronze medals). Since the Soviet team won 55 gold and 132 medals overall, it cost the Sports Committee about a million rubles (almost half paid in dollars) in bonuses alone.

James Riordan, “Sport after the Cold War: Implications for Russia and Eastern Europe”

More Interviews