The Swiss newspaper L’Express summarized it best:

Until the last moment, it was impossible to predict who would win the individual all-around victory. However, since the start of the evening, it was certain that the Japanese would win the team competition.

Jusqu’au dernier moment, il était impossible de prédire à qui irait la victoire individuelle. Par contre, depuis le début de la soirée, il était certain que les Japonais l’emporteraient par équipes.

L’Express, Saturday, October 26, 1968

Let’s take a look at what happened.

Results | Judging Assignments | Competition Notes | Commentary on Judging

Results

Date of Optionals: Thursday, October 24, 1968

Reminder: There wasn’t a separate team final or a separate all-around final. Both the team medals and all-around medals were determined on the same day — based on the compulsory scores and the optionals scores.

Refresher

Here were the top 5 teams after compulsories.

- Japan – 286.40

- Soviet Union – 285.15

- East Germany – 277.50

- Czechoslovakia – 276.50

- Poland – 275.15

Here were the top 5 individuals after compulsories.

- Voronin, URS – 57.90

- Nakayama, JPN – 57.60

- Kato, S., JPN – 57.50

- Kenmotsu, JPN – 57.10

Kato, T., JPN – 57.10

Diomidov, URS – 57.10

Final Team Results

| Country | Rank after Comp. | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 1. Japan | 1 | 286.40 | 289.50 | 575.90 |

| 2. Soviet Union | 2 | 285.15 | 285.95 | 571.10 |

| 3. East Germany | 3 | 277.50 | 279.65 | 557.15 |

| 4. Czechoslovakia | 4 | 276.50 | 280.60 | 557.10 |

| 5. Poland | 5 | 275.15 | 280.25 | 555.40 |

| 6. Yugoslavia | 6 | 273.15 | 277.60 | 550.75 |

| 7. USA | 9 | 271.60 | 277.30 | 548.90 |

| 8. West Germany | 10 | 271.25 | 277.10 | 548.35 |

| 9. Switzerland | 8 | 272.00 | 276.20 | 548.20 |

| 10. Finland | 7 | 272.05 | 275.85 | 547.90 |

| 11. Bulgaria | 12 | 268.50 | 269.65 | 538.15 |

| 12. Italy | 11 | 270.65 | 266.45 | 537.05 |

| 13. Hungary | 13 | 264.05 | 271.20 | 535.25 |

| 14. Mexico | 14 | 255.30 | 262.95 | 518.25 |

| 15. Cuba | 15 | 252.30 | 264.55 | 516.85 |

| 16. Canada | 16 | 250.05 | 260.35 | 510.40 |

All-Around Results – Top 20

| Name | Country | Comp. | Opt. | Total |

| 1. Kato S. | JPN | 57.50 | 58.40 | 115.90 |

| 2. Voronin | URS | 57.90 | 57.95 | 115.85 |

| 3. Nakayama | JPN | 57.60 | 58.05 | 115.65 |

| 4.Kenmotsu | JPN | 57.10 | 57.80 | 114.90 |

| 5. Kato T. | JPN | 57.10 | 57.75 | 114.85 |

| 6. Diomidov | URS | 57.10 | 57.00 | 114.10 |

| 7. Klimenko | URS | 56.70 | 57.25 | 113.95 |

| 8. Endo | JPN | 56.35 | 57.20 | 113.55 |

| 9. Cerar | YUG | 56.55 | 56.75 | 113.30 |

| 10. Karasev | URS | 56.70 | 56.55 | 113.25 |

| 11. Kubica, W. | POL | 56.40 | 56.75 | 113.15 |

| 12. Brehme | GDR | 56.25 | 56.60 | 112.85 |

| 13. Kubica, M. | POL | 55.90 | 56.90 | 112.80 |

| 14. Lisitsky | URS | 56.55 | 56.05 | 112.60 |

| 15. Ilinykh | URS | 55.75 | 56.15 | 111.90 |

| 16. Köste | GDR | 56.20 | 55.65 | 111.85 |

| 17. Nissinen | FIN | 55.70 | 55.90 | 111.60 |

| 18. Tsukahara | JPN | 55.45 | 56.05 | 111.50 |

| 19. Kubíčka | TCH | 55.35 | 55.95 | 111.30 |

| 20. Fejtek | TCH | 54.75 | 56.45 | 111.20 |

Judging Assignments

From the official program:

Floor Exercise

Judge-Referee:

Valentin Muratov (URS)

Alfred Schmidt (DDR)

Kaneko Akitomo (JPN)

Nicolai Kouly (BUL)

Luis de Pablo (CUB)

Pedro Ortega (MEX)

Jorge Tirado (MEX)

Note: My assumption is that Ortega and Tirado were line judges.

Pommel Horse

Judge-Referee:

Alex Lylo (TCH)

Heinz Neumann (GDR)

Zbigniew Noskiewicz (POL)

Gianfranco Marzolla (ITA)

Marcel Adatte (SUI)

István Sárkány (HUN)

Rings

Judge-Referee:

George Gulack (USA)

Milos Stergar (YUG)

Esa Seeste (FIN)

Raúl Oliveros (MEX)

Takemoto Masao (JPN)

Vault

Judge-Referee:

Pierre Hentgès (LUX)

Eberhard Pollrich (GDR)

Zdeněk Růžička (TCH)

Albert Dippong (CAN)

Sotero Tejada (PHI)

Enrique Sánchez (MEX)

Víctor Perea (MEX)

Note: My assumption is that Sánchez and Perea were the zone judges for hand placement.

Parallel Bars

Judge-Referee:

Rudolf Spieth (DDR)

Boris Shakhlin (URS)

Nilos Kaleka (TCH)

Georges André (FRA)

Fritz Feuz (SUI)

High Bar

Judge-Referee:

Tuomo Jalantie (FIN)

Rolf Bauch (GDR)

Armando Vega (USA)

Konstantin Darakachians (URS)

Tadeuzs Bettyna (POL)

Reserve Judges:

Jerry Hardy (USA)

Tomás Vivian (MEX)

Competition Notes

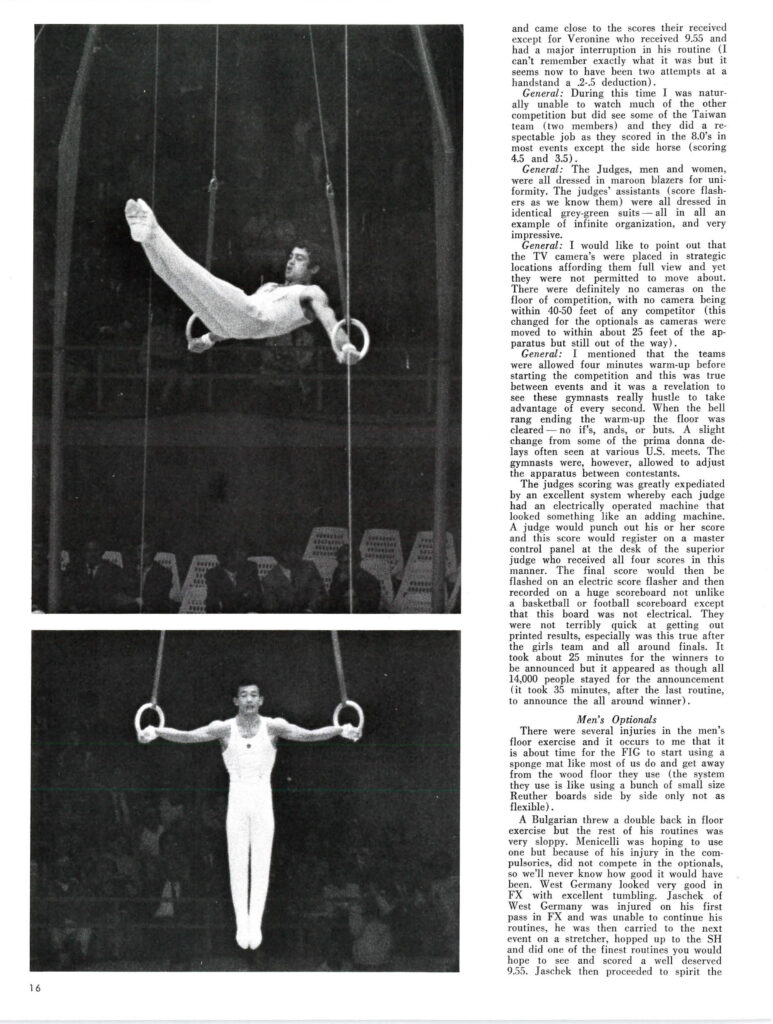

Kato Sawao’s victory was due to a stronger ring routine.

Sawao Kato’s victory was due to Voronin’s slight failure on the rings, which earned him a 9.70 while Kato was awarded a 9.85.

La victoire de Sawao Kato est due à une légère défaillance de Voronine aux anneaux, ce qui lui valut un 9,70 alors que Kato avait été gratifié de 9,85.

L´Impartial, October 26, 1968

Reminder: Voronin won rings at the 1966 World Championships, where he received two 9.90s on the event. The expectation was that he would score higher than a 9.70.

Kato Sawao was also really strong on floor.

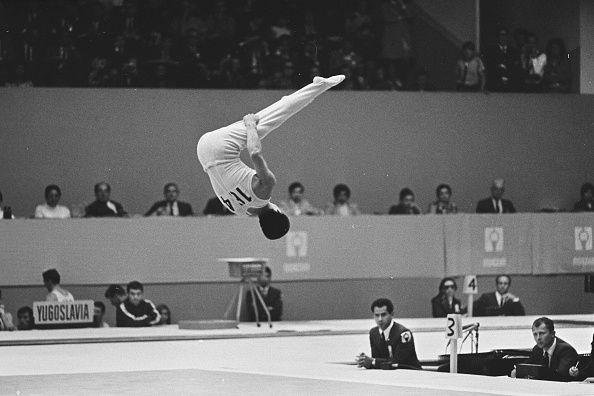

His risks paid off on floor. He scored a 9.90 to secure the all-around title. That was the highest score of the Olympic Games on the men’s side.

In die vrije oefening behaalde Kato 9.90 Punten en dat was net voldoende om Wereldkampioen Voronin en de ongetwijfeld talentvollere Nakayama voor te blijven. Toch kwam Kato’s zege voor de 13.000 toeschouwers niet geheel onverwacht. De Japanner stond bekend als de meest regelmatige turner m zijn Ploeg.

Limburgsch dagblad, October 26, 1968

You can watch a portion of his routine here:

The crowd went wild for his floor performance:

When Kato scored his 9.90 tally — 10 points is perfect — the crowd chanted wildly, “Kato, Kato, Kato” even before the score was flashed on the board.

The Yomiuri, Oct. 26, 1968

However, the Soviet press felt that he was overscored.

It was the moment when the road to the gold step of the podium opened for Sawao Kato. There was only one nuance: by the end of the day, he had to score at least 9.90 points in floor exercises. The task is almost impossible considering that over the past four days of the gymnastic tournament such a high score was given only once. The Japanese student successfully performed the swift tangles of his combination: the scoreboard showed his desired numbers – 9.90.

And yet, there were some mistakes. These two mistakes were enough to reduce the score by at least one and a half to two tenths of a point. The fact that the judges, to put it mildly, were so liberal about the errors of the Japanese gymnast was truly unexpected. What was even more surprising that Muratov, a judge from Moscow, who made part of the floor exercises judges team, accepted this obviously exaggerated score. Wasn’t the title of Olympic champion at stake?

Sovetsky Sport, Oct. 26, 1968

В этот момент перед Савао Като открылась дорога на верхушку пьедестала почета. Было только одно «но»: для этого нужно было получить на финише дня — в вольных упражнениях не меньше 9,90 балла. Задача почти невозможная, если принять во внимание, что оценки судей за минувшие четыре дня гимнастического турнира лишь один раз доходили до таких пределов. Стремительные хитросплетения своей комбинации японский студент выполнил удачно: на табло зажглись желанные для него цифры — 9,90.

И все же ошибки у Като были — две, не очень большие, но за которые надо было снижать оценку минимум на полторы-две десятых балла. Странно, что судьи, мягко говоря, либерально отнеслись к просчетам японского гимнаста. И еще более чем странно, что москвич В. Муратов — арбитр в бригаде судей на вольных упражнениях, по сути дела, смирился с явно завышенной оценкой. А ведь речь шла о том, кому быть олимпийским чемпионом!

A Comparison of Scores

| Kato S. | Voronin | |

| Compulsories | ||

| Floor | 9.75 | 9.55 |

| Side Horse | 9.45 | 9.70 |

| Still Rings | 9.70 | 9.75 |

| Long Horse | 9.35 | 9.45 |

| Parallel Bars | 9.65 | 9.75 |

| Horizontal Bar | 9.60 | 9.70 |

| Optionals | ||

| Floor | 9.90 | 9.70 |

| Side Horse | 9.55 | 9.50 |

| Still Rings | 9.85 | 9.70 |

| Long Horse | 9.55 | 9.55 |

| Parallel Bars | 9.70 | 9.70 |

| Horizontal Bar | 9.85 | 9.80 |

Perhaps Kato’s lead victory should have been more decisive?

In Jerry Wright’s opinion, Voronin was over-scored.

Voronin’s FX routine was a laugh as he did only three or four passes of basic moves (did most of them very well but had little difficulty and made three mistakes of some significance) and received 9.7. He then turned around and suffered a major break on the side horse and received a score of 9.5 !!!! (now by major break I mean like hitting and horse and stopping – which he did – or sitting on the horse).

Modern Gymnast, Nov./Dec. 1968

Note: It wasn’t just Jerry Wright who thought that Voronin was over-scored on floor. The crowd thought so, as well. Here’s what a Japanese newspaper reported:

In the next-to-last event for Russia, the floor exercise, Voronin’s score of 9.70 was loudly scorned by the crowd, which thought his performance was not that good.

The Yomiuri, Oct. 26, 1968

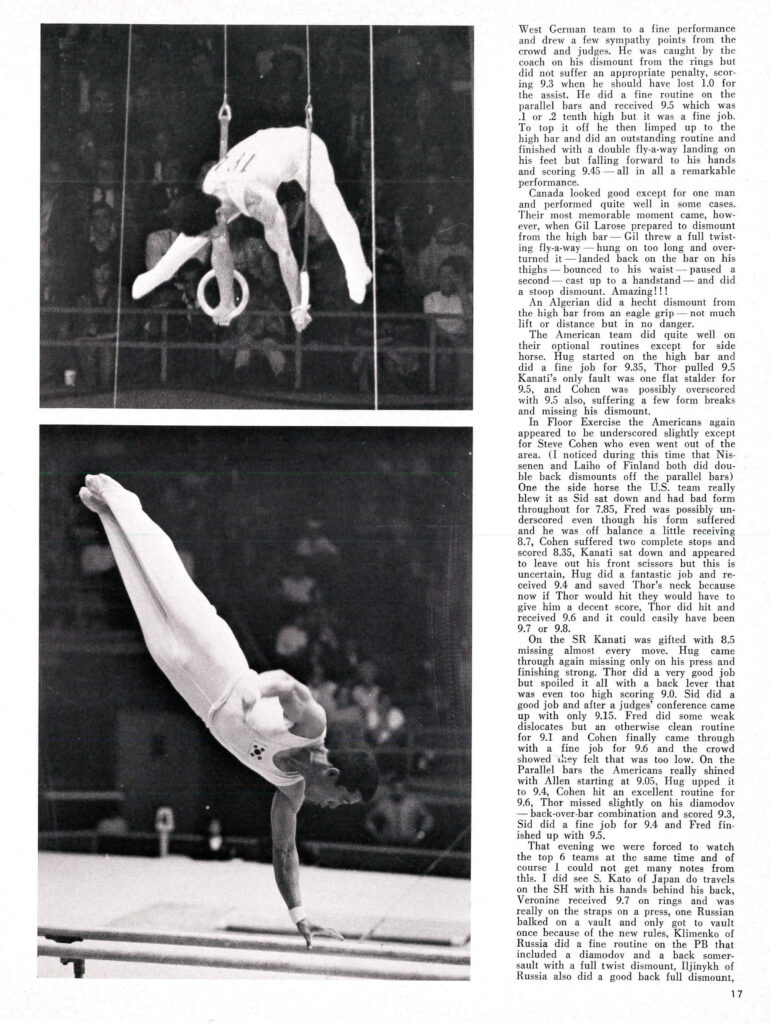

Another day, another gift (?) for Diomidov on parallel bars

Diamodov on the parallel bars again was gifted as he missed his Diamodov spread his feet, bent his arms and knees and took 4 or 5 steps and received 9.45.

Modern Gymnast, Nov/Dec 1968

The Men’s Optionals were wild: Part 1

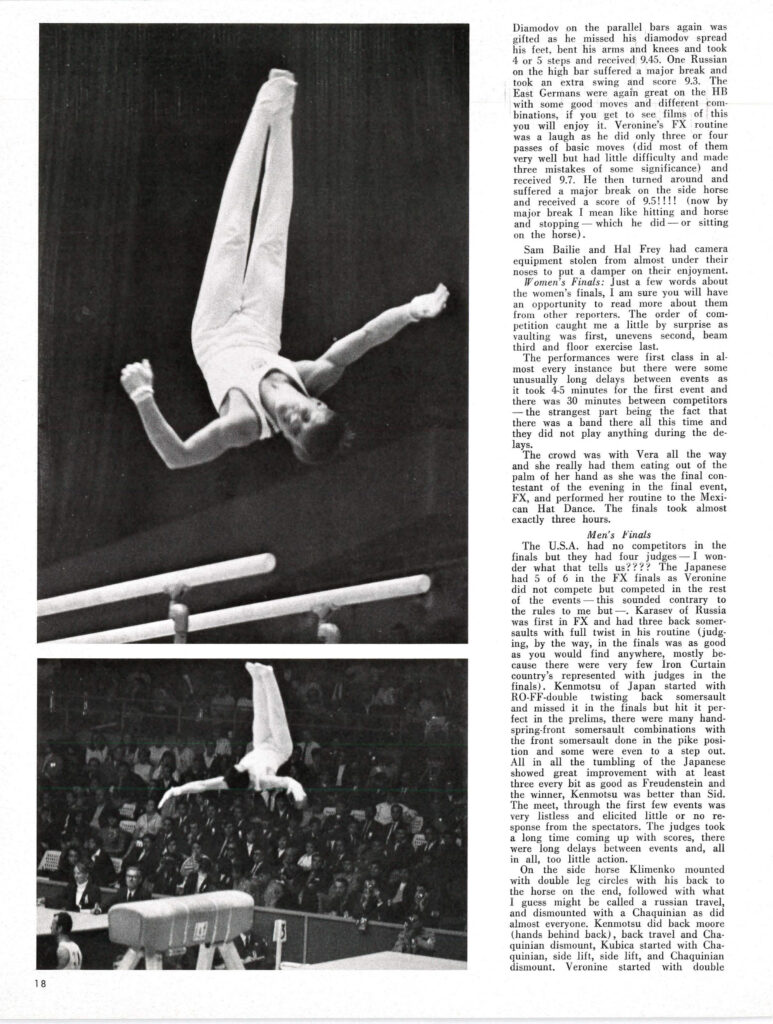

Willi Jaschek of West Germany tore his Achilles on floor, the team’s very first event. He went on to compete on pommel horse, rings, parallel bars, and high bar.

You can read the full story here.

The Men’s Optionals were wild: Part 2

Canada’s Gil Larose performed two different high-bar dismounts. The first time, he landed on the bar.

Canada looked good except for one man and performed quite well in some cases. Their most memorable moment came, how· ever, when Gil Larose prepared to dismount from the high bar – Gil threw a full-twisting flyaway — hung on too long and overturned it — landed back on the bar on his thighs — bounced to his waist — paused a second — cast up to a handstand — and did a stoop dismount. Amazing!!!

Modern Gymnast, Nov/Dec 1968

Two Double Back Dismounts off Parallel Bars

At the 1966 World Championships, Laiho performed a double back off parallel bars. Finland came to Mexico City with two double backs:

I noticed during this time that Nissenen and Laiho of Finland both did double back dismounts off the parallel bars.

Modern Gymnast, Nov./Dec. 1968

Team USA struggled on pommels.

One the side horse the U.S. team really blew it as Sid sat down and had bad form throughout for 7.85, Fred was possibly underscored even though his form suffered and he was off balance a little receiving 8.7, Cohen suffered two complete stops and scored 8.35, Kanati sat down and appeared to leave out his front scissors but this is uncertain, Hug did a fantastic job and received 9.4 and saved Thor’s neck because now if Thor would hit they would have to give him a decent score, Thor did hit and received 9.6 and it could easily have been 9.7 or 9.8.

Modern Gymnast, Nov./Dec. 1968

You can watch Hug’s routines here:

Team Canada sent a 5-member team but had its best team total to date.

It is recommended that Canada send full gymnastic teams to international meets, i.e. 6 men, 6 women, plus 1 spare each. Most teams in Mexico had 2 spares. With a sixth member, Canada would have had the chance to beat some countries. With only 5 members it is too difficult. In order to compete in the next Olympics, we must have some dual matches against European teams during the next 4 years.

Our biggest achievement, especially with only 5 competing gymnasts, was to have attained for the first time a team total of over 500 points.

Willy Weiler, Modern Gymnast, March 1969

Commentary on the Judging

Conflicts of Interest

You may have noticed that Jerry Wright in Modern Gymnast thought that Diomidov received several “gift” scores.

According to the work plan, here were the judges assigned to parallel bars for the compulsories (Ia). (Note: The work plan includes the assignments before the Olympics start. The assignments can change at the actual Olympics.)

Superior judge: Rudy Spieth GER

Boris Shakhlin, URS

Nilos Kaleka TCH

Georges Andre, FRA

Marcel Adette, SUI

And for the optionals (Ib):

Superior judge: Rudy Spieth GER

Boris Shakhlin, URS

Nilos Kaleka, TCH

Georges Andre, FRA

Fritz Feuz, SUI

Assuming that the work plan was followed, Boris Shakhlin competed at the 1966 World Championships and then judged several of his former teammates at the 1968 Olympics. You might call that a conflict of interest. (Similarly, Fritz Feuz competed at the 1964 Olympics and was judging one of his former teammates — Berchtold — in 1968.)

Not to mention that Shakhlin went from competitor to Olympic-level judge in just two years.

Granted, the Code of Points did favor former gymnasts:

As mentioned in the beginning, the judge’s own abilities and knowledge as a former gymnast, technical know-how and skill, continuous observation of the trends and development in artistic gymnastics, nationally and internationally, and unrestricted knowledge of the rules and regulations are necessary for conscientious judging.

1968 Code of Points, Article 71.E.2

But Shaklin’s timeline raises the question: How much judging experience did someone need to be an Olympic-level judge in 1968?

Note: Shakhlin would be accused of attempted score-fixing at the 1976 Olympics. You can read the allegations here.

(Many thanks to Hardy Fink for supplying the judging assignments.)

Mixed opinions on the judging from the Americans

Against the Judging

You saw Jerry Wright’s comments on Diomidov and Voronin above. American gymnast Dave Thor echoed Wright’s sentiments, suggesting that the judging was lousy.

The Mexican people viewed the gymnastic competition with all the enthusiasm and fervor of a crowd packed into a bullfighting stadium. If the judges threw out a bad score, the crowd would respond accordingly. Unfortunately, the auditorium was in an uproar during a lot of the competition, which doesn’t say a whole lot for the judging.

Modern Gymnast, Nov/Dec 1968

In Favor of the Judging

American judge Gene Wettstone, on the other hand, thought it was the best judging to date:

But, looking at the whole picture and glancing back at the past, this judge would have to say it was the best all-around judging performance ever experienced.

Modern Gymnast, Nov/Dec 1968

During the FIG judging course in Rome, it was made clear that bias would not be tolerated.

More power was delegated to the superior judges who were given the authority to expel any judge who scored inaccurately or showed partiality.

Modern Gymnast, Nov/Dec 1968

Arthur Gander reminded the judges that they would be scrutinized by the world and the FIG.

Mr. Gander did not mince any words with the judges. He demanded the highest integrity from each one when he said, “The eyes of the world will be directed upon you (TV coverage). This is good propaganda for gymnastics internationally.” “We require special effort from all of you and we will also review your scores following the Games to evaluate your status as a future international judge.”

Modern Gymnast, Nov/Dec 1968

According to Wettstone, there was less political jockeying in 1968 than there had been in the past.

Now that the Games are History and I have had time to review my thoughts, I can honestly say that as a former coach and judge I saw a marked improvement in unbiased and knowledgeable judging at these Games; not perfect, but so much better and on the right road to future improvement. There was less political pressure as a result of the Code of Points . . . a marvelous measuring stick of modern gymnastics. The national flag or names did not seem to affect scores and judges’ opinions were not flashed but were transmitted by elaborate electrical core boxes to a monitor at the superior judges desk. In other Games the usual bargaining or propaganda was quite the fashion, but in Mexico City the emphasis was on the rules and the judging of performances not men or teams.

Modern Gymnast, Nov/Dec 1968

My thought bubble: He didn’t say that there wasn’t any political pressure. There was simply less of it.

A Brief History of Judging

And from the sounds of it, there used to be a lot of political jockeying. Here’s how Gene Wettstone tells the history of judging — don’t take this as absolute fact:

The Judging at Mexico City surely was a hundred times better than it was in Mr. Arthur Gander’s childhood days as he described it to the U.S. coaches at their annual Gymnastic Congress in Chicago. There was a time when a judge would leisurely sit at a table near the apparatus with a cigar in his mouth and a bottle of wine on the table. Judging in those days, according to Mr. Gander, was on a general impression and the judge’s likes and dislikes … or whether the gymnast hailed from a small, primitive village or from a more worldly and educated big city environment. You might also say that it was at least eighty times better than the judging at the 1936 Games in Berlin where the superior German atmosphere led to scores in favor of the political power of the day. There were no rules for scoring and those who were used as judges were chosen not for their competency or qualifications, but because they just happened to be the manager of the team without any coaching duties or were able to afford the financial expenditures of the trip. As coach of the U.S.A. team in 1948 in England, I saw Mr. Gander, then the team leader from Switzerland, battle it out with a veteran and courageous Finnish team. I can recall the disturbed Mr. Gander and the exasperated expression on his face as he thought about the inadequacies of judging and the lack of more objective ways of measuring exercises.

Mr. Gander pointed out in the new Code of Points Book that in 1948 the differences between the scores awarded by the different judges were so great that inaccurate judging was unavoidable. It was after these Olympic Games that the first definite and comprehensive set of rules were created, appearing in the year 1949 under the name “Code de pointage.” The booklet of 12 printed pages had separate evaluations for difficulty, combination, and execution. Compare that, if you will, with the present Code of 167 pages.

One might also say that the 1968 judging was forty times better than in 1952 when upon the arrival of the Soviet Gymnasts, it was obvious that the progress had already surpassed these new regulations. Judging was very biased and there was a great deal of East-West political favoritism. Rules had to be formulated to meet the new trends and to combat subjective and nationalistic judging. Tension still existed between Eastern and Western block nations in 1956, but the International Gymnastic Federation with its fine technical committee led by President Arthur Gander developed further regulations and the A.B.C. skill values along with better understanding of the combination factors.

Modern Gymnast, Nov/Dec 1968

My thought bubble: I don’t doubt that a 167-page Code of Points helped reduce subjectivity and ambiguity — but a 167-page Code of Points is useful only if it is followed and enforced. It won’t automatically put an end to political jockeying and bias.

On the topic of judging, Canada didn’t pay for its judges’ travel to the 1968 Olympics.

There were four officials active in judging. However, they were not financially or materially aided by the Olympic Association. Fay Weiler, Maria Medvecky, Albert Dippong, and Jacques Chouinard deserve great credit for their fine showing in judging. The biggest step towards international recognition has been achieved as our judges proved to be well qualified and did an excellent job.

Wilhelm Weiler, Modern Gymnast, March 1969

My thought bubble: If a judge’s federation signs his paycheck, is he going to be an objective, independent judge, or will he do as his federation wants him to do?

Appendix: Allegations of Attempted Score Fixing by Shakhlin in 1976

In 1976, here’s what the English-language newspaper The Daily Yomiuri reported about Shakhlin’s actions as the head judge:

Both Wettstone and Frank Bare, the executive director of the US gymnastics federation, charged Soviet head judged Boris Chakhlin [Shakhlin] with trying to get scores changed during the finals of the team competition Tuesday night. The incidents came as Russia battled Japan down to the wire for the men’s championship.

Chakhlin was head judge at the horizontal bar. One of the Japanese gymnasts received two 9.9s, a 9.8 and a 9.7 from the four judges. Under the rules, the high and low scores were thrown out and the other two were averaged, which would give the gymnast a 9.85 in this case.

Chakhlin, under the rules of gymnastics judging, would not be allowed to intervene unless he felt there was a significant discrepancy in one of the scores. The Americans said they felt no major discrepancy existed. But Chakhlin called a conference and tried to get the East German judge to lower the score from 9.9 to 9.8. The result would have been that the gymnast would have received a 9.8 instead of a 9.85.

“We sat behind him (Chakhlin) and wrote down all the scores because we were concerned,” said Bare. “We all hollered and the Japanese judge protested when Chakhlin called a conference, and the score was not changed.”

Bare said the same thing occurred when the first Soviet gymnast reached the horizontal bar. Chakhlin called a conference and tried to persuade a French judge to make his score higher, which would have moved the Russian from a 9.6 to 9.65. But again the score was not changed due to protests from the Americans watching and the Japanese judge.

The Daily Yomiuri, July 25, 1976

Again, these were allegations. Shakhlin would be on the Men’s Technical Committee from 1969 through the early 1990s.

More from 1968