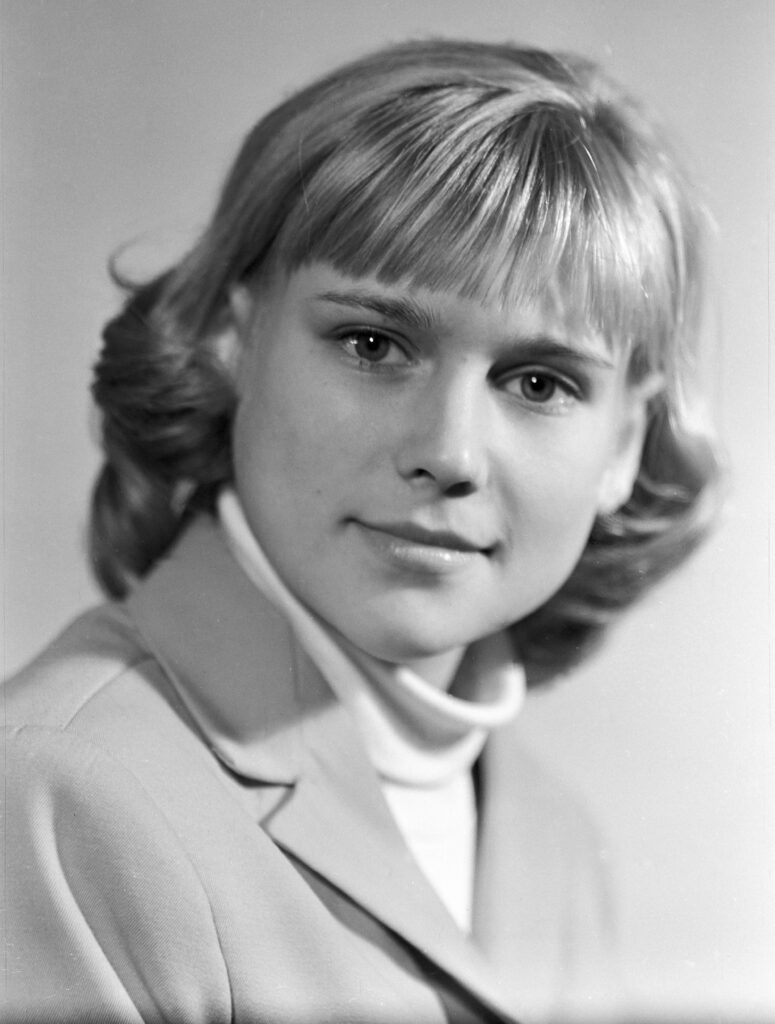

Olga Karaseva won Olympic gold in 1968, became world champion in 1970, and won medals on every event at the 1969 European Championships—taking silver in the all-around and gold on floor. Her career blazed briefly but brilliantly, embodying the elegance that made Soviet gymnastics compulsory viewing in those years. But by twenty-three, she was finished competing and felt, as she puts it, that “no one needed me anymore.”

In this 1990 conversation with sports writer Gennady Semar, Karaseva examines what the Soviet system did to athletes: how it created champions and then abandoned them, how it corroded the moral foundations that once made sport meaningful. She speaks with unusual candor about the collapse of purpose after competition ends, the loss of expertise as former athletes drift into bureaucratic roles, and the absence of any social safety net once the applause stops. Yet she’s not bitter. She counts herself fortunate—her coaches were “people of high human qualities,” and she escaped both the coercive “stick” of brutal training and what she calls the “chemicalization” of sport, a process she describes as “the destruction of the soul” that ruins both health and integrity.

For Karaseva, the crisis isn’t only institutional or pharmacological—it’s spiritual. Athletes, she insists, must be understood not as expendable performers but as whole people whose cultural development, imagination, and artistry are inseparable from their physical achievements. To save sport, she argues, means recognizing athletes as creators, not gladiators.

Note: Olga Karaseva passed away at the end of October at the age of 77.

ETERNAL VALUES

IMAGINE YOURSELF A CREATOR

Sport has many faces. It is not only “goals, points, seconds.” It is also people: athletes, coaches, friends, fans. It is a world of inspiration, of rises and falls, of glory and disgrace, of love and disappointment. It is life itself…

About all this and much more reflect Olympic champion gymnast Olga KARASEVA and writer, deputy chairman of the Federation of Sport Writers of the USSR, Gennady SEMAR.

G. S. It is customary to compliment women. I will not be an exception and will say that I admired you, Olga, and your teammates — Zina Voronina, Natasha Kuchinskaya, Larisa Petrik. In those years, fans watched gymnastics with the same rapture as football. There were two reasons for this “fever” — the complexity of the sport and the fairy-tale beauty of our girls. This tradition has been preserved in every new generation of the team. Whole countries could not resist you, whether in Mexico or Finland, Italy or France, Austria or Australia… This tradition continues even today, though we, alas, have grown somewhat older. But our love of sport remains…

O. K. For as long as I can remember, my whole world was sport. Newspapers, television, postcards of famous athletes in kiosks — even the statue of the athlete in the niche at the entrance to the “Revolution Square” metro station thrilled me, until it somehow disappeared…

G. S. Yes, the years go by, generations pass. But, unfortunately, problems in sport remain. They even multiply, becoming more complex and more painful. This is especially true for those we call “stars.” To them, one may apply an astronomical metaphor: great stars burn more brightly, exhaust themselves more quickly, and collapse into “black holes.” Athletes are often compared to artists, but people forget the crucial difference: an artist is forever; it is a profession for life; but an athlete — only for a time, sometimes a very short one. For that reason alone, an athlete cannot be a professional for life; for that reason alone, someone who has entered great sport requires a completely special kind of treatment. Do you agree with me, Olga?

O. K. I agree. At the age of twenty-three, I had already finished competing and felt that no one needed me anymore. I was not ready for this, just like many other athletes. I did not consider myself capable of coaching. I had not studied at a sports institute, as is typical for athletes, but at the Krupskaya Pedagogical Institute. I worked at the USSR State Sports Committee, paved the road to international judging, and when I had just established myself there, I was pushed aside. For a time, I worked on the television program Warm-Up. Now, thanks to knowing foreign languages, I continue to work at the USSR State Sports Committee, supervising wrestlers. Gradually, I am losing my qualification as an international judge, losing my sporting experience, my knowledge of the gymnastics world.

My fate, as you see, cannot really be called tragic: compared to the fates of many athletes, my life is, in general, a normal one. But the problems are there, and together with thousands of other destinies they illustrate the law of the transformation of quantity into quality: the general lack of protection of the athlete’s personality, especially those “retired”; their state of dissatisfaction, which gives rise to apathy or unmotivated actions or unmotivated violence — this is the dramatic circle of our conversation. It is especially hard for athletes in my sport — gymnastics. Unlike hockey players, we cannot go “at the end of our careers” to earn money abroad.

G. S. Indeed, if a young man chooses the sporting path in life, his biography develops mostly thanks to natural talent and the “stick” of his coach. Then comes stagnation. The strongest leave the arena, doping comes into play, and then — a sad finish… Well, someone might say, you decided to be a gladiator, don’t complain that the blows hurt! True, something is beginning to change now, gradually. In a new project, provision is made for a decent pension — so far, however, only for famous athletes…

O. K. True. As for the “stick” and doping, I was fortunate to avoid them. First of all, because my mentors were people of high human qualities — Sofia Muratova, the Zhukovs. And also because the “chemicalization” of sport had not yet reached us at that time. I see the doping problem as one among many leading to the destruction of the soul and the ruin of people’s health. In the field of physical culture, such problems are countless in number. The program Sport and Health is barely breathing, or, more likely, has long since breathed its last!

[Note: This article inspired me to dive into another topic, and we will take a look at the chemicalization of gymnastics (i.e., doping) in future articles.]

O. K. If we cannot give athletes good financial support, then at the very least we must provide them with moral and social security for the present and the future. Athletes themselves are taking the initiative, creating a people’s, essentially grassroots, sports union. They only need support. Without officials, I think, this could solve the urgent professional problems.

G. S. And so we have come to the problems of perestroika in sport. We broke apart a system that had developed over decades, without imagining what lay behind the concept of “professional”! Could it really be that specialists did not understand that at this stage it was unfeasible? What happened was the same as with the theatrical experiment, with the anti-alcohol campaign, with many other “accelerations” and “state commissions” that did not fit into our national character. In sport, it turned out that our “professionals” looked only abroad, while mass sport was left to count pennies. Action gave rise to reaction: if one has to pay to visit a gym or a court, then we will not go at all — even for free! Much has been turned upside down.

O. K. As for the specialists, most likely they were not asked, just as we veterans were not. Personally, I do not see sport as mere physical culture, but as a calling. Probably happy is the one who, in youth, found his calling. In this sense, it is good that today’s youth have become more pragmatic. But they must know that our sport has its own specific character, its own scale of values, and these must be respected. Otherwise, nothing will work.

Olympic champion [in diving] Elena Vaytsekhovskaya, who became a sports journalist, once said in an interview, answering the question of why young athletes, full of strength, leave sport: “They cannot withstand the psychological pressure!” And what is being done in our country in this respect?

…But let us return to the question of professionalism. Allow me to quote the head of the Laboratory of International Sports Movements at VNIIFK, Candidate of Historical Sciences S. Guskov: “Of the 307 members of national teams surveyed across 15 sports, as well as 9 master teams in team sports, 83 described themselves as amateurs, 130 as professionals, 94 found it difficult to answer… Of the 10 members of the national gymnastics team, 8 considered themselves semi-professionals.”

In a recent television program Arena, the chairman of the USSR State Sports Committee, N. Rusak, warned against universal professionalism, which is harmful to mass sport. He said that on the horizon is the first congress of workers in physical culture and sport, and in preparation, a Law on Physical Culture. This is encouraging. As he put it: “We do not have an institute of people’s physical culture, and it is up to us to create it.”

G. S. Indeed, we do not have a coherent program of physical education, beginning from kindergarten. Here, I think, sports veterans could bring great benefit. And writers too. One could make a contribution to the creation of an alternative program, or at least set down one’s thoughts after studying the draft — all the more since the Federation of Sport Writers of the USSR still exists…

In this vein, I would like to say the following: today, few coaches connect the overall cultural development of athletes with the growth of their results. I know personally that your teammate, Olga, now coach Natasha Kuchinskaya, and the youth basketball team coach Yevgeny Gomelsky, attach importance to this: their pupils go to exhibitions, dance, and in their program are theater and literature… This is very important! Culture forms personality, and personalities make great sport. I proceed from what has long been known: coordination of movements and other physical abilities of a person may be inborn, but may also be acquired. The doctor and scientist Burdenko once remarked that a man with a vivid imagination makes fewer mistakes than a conscientious pedant, that every person must be an artist. In other words, the spiritual world of a person is inseparable from his physical condition. But do we have time for this today? As the saying goes: no bread, no worthy spectacles!* Yet to think about culture, including physical culture, is essential — otherwise we shall never see success!

[*Note: The phrase “ни хлеба, ни зрелищ” (literally “neither bread nor spectacles”) is a twist on the famous Roman expression “panem et circenses” — “bread and circuses.” In ancient Rome, that phrase described how rulers kept the populace content by providing free food (bread) and entertainment (circuses, games). The Russian variant flips the idea: “no bread, no spectacles” means that people today lack both material well-being and inspiring cultural life. So in this passage, the speaker is lamenting that society provides neither the basics (“bread”) nor uplifting, meaningful experiences (“worthy spectacles”), implying both economic hardship and cultural impoverishment.]

O. K. We need to bring people back to the stadiums — and not only as spectators. And stadiums shouldn’t be used just for rock concerts. I recall the words of my friend, the celebrated athlete Yelena Petushkova: “I didn’t come to sport for the medals. I needed victory — only I understand it in my own way: to achieve something greater than what I’m capable of!”

Sovetsky Sport, no. 161, July 14, 1990

ВЕЧНЫЕ ЦЕННОСТИ

ВООБРАЗИ СЕБЯ ТВОРЦОМ

Спорт многолик. Он не только «голы, очки, секунды». Он — и люди: спортсмены, тренеры, друзья, болельщики. Это — мир вдохновения, взлётов и падений, славы и бесславия, любви и разочарования. Это — жизнь…

Обо всём этом и многом другом размышляют олимпийская чемпионка гимнастка Ольга КАРАСЕВА и писатель, заместитель председателя Федерации литераторов о спорте СССР Геннадий СЕМАР.

Г. С. Женщинам положено говорить комплименты. Я не стану исключением и скажу, что восхищался вами, Ольга, и вашими подругами по команде — Зиной Ворониной, Наташей Кучинской, Ларисой Петрик. В те годы болельщики с восторгом следили за спортивной гимнастикой, так же, как за футболом. Были две причины этой «болезни» — сложность этого вида спорта и сказочная красота наших девушек. В команде каждого нового поколения эта традиция сохранилась. И перед вами не могли устоять целые страны, будь то Мексика или Финляндия, Италия или Франция, Австрия или Австралия… Эта традиция сохраняется и сегодня, а мы, увы, несколько постарели. Но сохраняем любовь к спорту…

О. К. Сколько себя помню, вокруг был мир спорта. Газеты, телевидение, открытки знаменитых спортсменов в киосках, волновала даже скульптура атлета в нише у входа на станцию метро «Площадь Революции», которая куда-то исчезла…

Г. С. Да, проходят годы, уходят поколения. Но, к сожалению, проблемы в спорте остаются. И даже множатся, становятся сложнее и болезнее. Особенно это касается тех спортсменов, которых принято называть звёздами. К ним позволительно применить такую астрономическую метафору: большие звёзды живут энергичнее, быстрее расходуют себя и становятся «чёрными дырами». Часто спортсменов сравнивают с артистами, забывая главную разницу, которая состоит в том, что артист — это навсегда, это профессия до конца жизни, а спортсмен — это на время, подчас на очень короткое. Уже только поэтому спортсмен не может быть профессионалом пожизненно, уже только поэтому к человеку, пришедшему в большой спорт, нужно совершенно особое отношение. Вы согласны со мной, Оля?

О. К. Согласна. Я уже в двадцать три года закончила выступления и ощутила себя никому не нужной. Не была готова к этому, как и многие другие спортсмены. Не считая себя способной к тренерской деятельности. Я училась не в инфизкультуре, что типично для спортсменов, а в пединституте имени Крупской, работала в Госкомспорте СССР, торила дорожку в международное судейство, а когда проторила, меня отодвинули. Одно время довелось создавать «Разминку» на телевидении. Сейчас, благодаря знанию языков, продолжаю трудиться в Госкомспорте СССР опекою борцов. Потихоньку теряю квалификацию судьи международной категории, теряю свой спортивный опыт, знания гимнастического мира.

Мою судьбу, как видите, всё же нельзя причислить к разряду драматических: в сравнении с судьбами многих спортсменов у меня в общем-то нормальная жизнь. Однако наличие проблем, которые вкупе с тысячами судеб других дают иллюстрацию закона о переходе количества в качество: общая незащищённость личности спортсменов, в основном «отставников», их состояние неудовлетворённости, что рождает апатию или немотивированные действия или немотивированное насилие — вот драматический круг нашего разговора. Особенно трудна спортсменам моего вида — гимнастикам. Мы, как и хоккеисты, — «под занавес» на заработки за рубеж не поедем.

Г. С. Действительно, если молодой человек избрал спортивный путь в жизнь, то его ждёт складывающаяся биография за счёт в основном природных данных и «кнута» тренера. Далее наступает застой. Арену покидают сильнейшие, идут в ход допинговые средства, после чего — печальный финиш… Что ж, скажет кто-то, решили стать гладиатором, не говори, что не дюк! Правда, сейчас кое-что начинает меняться, постепенно. В новом проекте о достойном пенсионном обеспечении ставится пока лишь для знаменитых спортсменов…

О. К. Верно. Что касается «кнута» и допинга, то лично мне этого удалось избежать. Прежде всего потому, что моими наставниками были люди с высокими человеческими качествами — Софья Муратова, Жуковы. Ещё и потому, что «химизация» спорта в те годы к нам ещё не пришла. Я рассматриваю допинговую проблему в ряду многих, ведущих к разрушению души и к краху здоровья людей. В области физкультуры они бесчисленны по сути. Программа «Спорт и здоровье» чуть дышит или, скорее, приказала долго жить!

О. К. Если мы не можем дать спортсменам хорошее денежное содержание, то по крайней мере должны обеспечить их настоящее и будущее в моральном и социальном плане. Сами спортсмены проявляют инициативу, создавая народный, по сути, спортивный союз. Их только нужно поддержать. Это без чиновников, думается, могло бы решить насущные профессиональные задачи.

Г. С. Вот мы и погрузились в проблемы перестройки в спорте. Мы сломали сложившуюся десятилетиями систему, не представляя себе, что стоит за понятием «профи»! Неужели специалистам было невдомёк, что на данном этапе это неосуществимо? Получилось то же, что и с театральным экспериментом, с антиалкогольной кампанией и многими другими «ускорениями» и «госприёмками», не вписавшимися в нашу национальную специфику. В спорте получилось так, что наши «профи» стали смотреть только в одну сторону — за бугор, а массовый спорт стал считать копейки. Действие родило противодействие: раз за посещение спортзала или корта надо платить, так мы вообще не пойдём, даже бесплатно! Многое встало с ног на голову.

О. К. Что касается специалистов, то их, скорее всего, не спросили, как и нас, ветеранов… Лично я рассматриваю спорт не как физкультуру, а как дело. Наверное, счастлив тот, кто в молодые годы нашёл своё дело. В этом смысле хорошо, что сегодняшняя молодёжь стала более прагматичной. Но молодёжь должна знать, что у нашего спорта есть своя специфика, своя шкала ценностей, и с ними надо считаться. Иначе ничего не получится.

Олимпийская чемпионка Елена Вайцеховская, ставшая спортивным журналистом, в одном из своих интервью, отвечая на вопрос: почему молодые ребята, полные сил, уходят из спорта, ответила — не выдерживают психологически! А что у нас делается в этом направлении?

…Но вернёмся к теме профессионализма. Позволю себе процитировать заведующего лабораторией международного спортивного движения ВНИИФКа, кандидата исторических наук С. Гуськова: «Из 307 опрошенных членов сборных команд страны, — написал он, — по 15 видам спорта, а также 9 команд мастеров по игровым видам, 83 человека назвали себя любителями, 130 — профессионалами, 94 ответить затруднились… Из 10 членов сборной команды страны по спортивной гимнастике 8 спортсменов считают себя полупрофессионалами».

В недавней телепрограмме «Арена» председатель Госкомспорта Н. Русак предостерёг от всеобщего профессионализма, который вреден массовому спорту. Он сказал, что на горизонте первый съезд работников физкультуры и спорта, а в стадии подготовки — Закон о физической культуре. Это обнадёживает. Как он выразился: «У нас нет института народной физкультуры, и нам его предстоит создать».

Г. С. Действительно, нет у нас стройной программы физического воспитания, начиная с детского сада. Вот здесь-то, думается, ветераны спорта могли бы принести немалую пользу. Да и писатели тоже. Можно внести свой вклад в создание альтернативной программы или, по крайней мере, изложить свои мысли, ознакомившись с проектом, — тем более, что Федерация литераторов о спорте СССР пока ещё существует…

В этой связи хочется сказать вот о чём: сегодня мало кто из тренеров связывает общее культурное развитие спортсменов с ростом его результатов. Лично мне известно, что ваша, Оля, подруга по сборной, ныне тренер Наташа Кучинская, да тренер сборной молодёжной по баскетболу Евгений Гомельский придают этому значение, их воспитанницы ходят на выставки, танцуют, и в их программе — театр, литература… Это очень важно! Культура делает личность, а личности делают большой спорт. Я исхожу из давно известного: координация движений и другие физические возможности человека могут быть врождёнными, а могут быть приобретёнными. Врач и учёный Бурденко однажды заметил, что человек с ярким воображением ошибается реже, чем добросовестный педант, что каждый человек должен быть художником. Иными словами, духовный мир человека неразделим с его физическим состоянием. Но до этого ли нам сегодня? Как говорится, ни хлеба, ни достойных зрелищ! Но думать о культуре, в том числе и о физической, необходимо, иначе нам удачи не видать!

О. К. Нужно возвращать людей на стадионы, и не только в качестве зрителей. И стадионы нужно использовать не только для выступлений рок-ансамблей. Вспоминаю слова моей подруги, нашей прославленной спортсменки Елены Петушковой: «Я в спорт пришла не ради медалей. Мне была нужна победа, только я ее по-своему понимаю: совершить нечто большее, чем то, на что способна! ».

More Interviews and Profiles