In November 2003, Ziarul de Sibiu (The Sibiu Newspaper) published this profile of Mihaela Stănuleț, who won team silver at the 1983 World Championships and won Olympic gold with Romania’s team in Los Angeles in 1984. The article captures the harsh realities facing retired gymnasts in post-communist Romania. Even Olympic champions struggled to find work, were asked to return their competition tracksuits, and trained new generations in unheated gyms with decades-old equipment.

Like many of her contemporaries, Stănuleț had competed underage: born in 1967, she was only 14 when she placed fourth with Romania’s team at the 1981 World Championships in Moscow, a year before she would have been eligible under the age-15 minimum. By the time she reached the Olympics three years later, the system that had rushed her into elite competition as a child offered little in return for her gold medal—just 16,000 lei instead of the promised 100,000 and no car despite assurances. (Ecaterina Szabó made similar remarks about unfulfilled promises.) The article reveals how completely Romania’s gymnasts were discarded once their competitive value expired.

Oh, and there’s a story about Béla Károlyi’s dogs.

The Olympic champion Is Freezing at the Sports School Club.

Next year marks two decades since Sibiu boasted its first Olympic gymnastics champion.

In 1984, at the Los Angeles Olympic Games, Mihaela Stănuleț won the gold medal with the Romanian team. For this exceptional performance, she received the “fabulous” sum of 16,000 lei. She didn’t even make it onto the priority list of the Sibiu County People’s Council for purchasing a color television. Rejected by I.E.F.S., and with the local state farm (IAS) as her first workplace, she discovered that when she retired from sport, they even took back her tracksuit.

Until three years ago—when Claudia Presăcan won the Olympic team title with Romania in Sydney—Mihaela Stănuleț had been the only gymnast from Sibiu to win an Olympic gold medal. She was born on 5 July 1967, in Sibiu in a working-class family. In 1974, a team of coaches, who were visiting Sibiu’s schools, suggested that her parents enroll their daughter in the gymnastics section of the sports school. Her first coaches were Rodica Filip (who has since moved to Austria) and Andrei Goreac, all under the coordination of emeritus coach Nicolae Buzoianu. After only six months, Mihaela took part in her first competition, in Deva. She would return there six years later, in 1980, this time as a member of the Olympic training squad under Béla Károlyi’s authority. She had just finished eighth grade. Life in a permanent training camp was hellish—seven hours of training a day, far from home and parents. At the same time, she still had to attend school.

Her international debut came just as quickly as her domestic one. In 1981, Mihaela Stănuleț took fourth place with the team at the World Championships in Moscow. The taste of medals came in Budapest. In 1983, again at the World Championships, Romania won the silver medal.

16,000 lei for an Olympic gold medal

After nearly ten years of titanic work, the sweet side of a gymnast’s life finally arrived. Mihaela earned worldwide recognition in 1984 at the Los Angeles Olympics. On American soil, a gymnast from Sibiu won the title that every athlete dreams of. Together with Ecaterina Szabó, Lavinia Agache, Cristina Grigoraș, Simona Păuca, and Laura Cutina—the sextet that formed Romania’s team—she won the team gold medal and placed fourth on uneven bars individually.

The joy of victory was short-lived and was followed by great disappointment. In the familiar style of the communist leadership of the time, true champions were barely appreciated—or not appreciated at all.

“When we returned to the country, they promised each of us a Dacia car and 100,000 lei. What we received was only a tiny fraction of what they promised. They gave each of us 16,000 lei—16,000 lei for an Olympic gold medal that required 17 years of hard work and heavy restrictions on our personal lives. I don’t even want to remember,” the gymnast said with regret.

End of career

The offense was far too great for Mihaela. She decided to end her competitive career.

“The Gymnastics Federation didn’t organize anything. Worse—unbelievably—they asked me to return the tracksuit I had worn in the United States. I can’t even describe what I felt in that moment. I felt excluded, discarded. Only the City Hall organized a small ceremony for me,” Mihaela recalls with tears in her eyes.

Her first job: a state farm (IAS)

But the nightmare didn’t end even after she quit competing. Mihaela’s disappointment deepened when she realized that after leaving competition, no one seemed to need an Olympic medalist.

“I had to find a job on my own. The School Sports Club (CSS Sibiu) welcomed me warmly, but they couldn’t pay me. So they hired me through a nearby IAS, even though I didn’t actually work there. I was taken ‘out of production.’ For two years—until 1987, when I was finally hired as a coach at CSS Sibiu—I worked with children in the gym every day, but my salary came from that IAS (State Agricultural Enterprise). Some things are forgotten too quickly.

[Note: An IAS (Întreprindere Agricolă de Stat) was a large, state-owned farm in communist Romania that operated as part of the centrally planned economy. Unlike cooperatives (CAPs), IAS units were fully managed by the state, used industrial-scale methods, and employed workers as state staff rather than collective members.]

In 1987, I took the entrance exam for I.E.F.S. (Institute of Physical Education and Sport), but I was rejected. I helped prepare Claudia Presăcan, together with Constanța Barbu, but no one remembers that anymore. I’m always listed under ‘…and others,’ even though for many years I was the only athlete from Sibiu with an Olympic medal in her home display case,” she notes.

She has not kept in touch with her teammates

Mihaela Stănuleț still lives in her parents’ home. This summer, she graduated from the Faculty of Physical Education and Sports Management at “Lucian Blaga” University of Sibiu, and now she is trying to find a little girl to follow in her footsteps at CSS, where she works as a coach and teacher. She is also a federation judge in the Romanian Gymnastics Federation.

Except for Simona Păuca, she is the only member of the 1984 “golden team” who remained in Romania. According to the information she has, Ecaterina Szabó is now a coach in France; Lavinia Agache settled in the U.S. with her husband; Cristina Grigoraș emigrated to Greece. Though they once shared the sweetness of the highest success, the team dispersed. Each went her own way, and they never kept in touch.

“I haven’t spoken to any of my former teammates since the year we won the Olympic medal. I haven’t spoken to Béla Károlyi either, even though he still comes to Romania sometimes. Everything I know about the girls, I know from newspapers or acquaintances,” Mihaela says.

An exceptional gymnastics program

Mihaela Stănuleț is only one of the stars of Sibiu’s gymnastics school. Marinda Neacșu, Melitta Rühn, sisters Camelia and Simona Renciu, Maria Antonie—these are famous names in Romanian gymnastics.

The women’s gymnastics section of the School Sports Club (CSS Sibiu) is the most decorated in the history of sports in Sibiu. It has accumulated over 25 medals at the Olympic Games, World Championships, and European Championships, senior and junior.

These include two Olympic titles (Mihaela Stănuleț – 1984; Claudia Presăcan – 2000), five world titles (Melitta Rühn – 1979; Claudia Presăcan – 1994, 1995, 1997; Sabina Cojocar – 2001), over 30 Balkan and International titles, and more than 80 medals brought to Sibiu in major competitions.

Sibiu gymnasts have performed more than 700 exhibitions on all continents, and in domestic competitions, they have won more than 1,000 medals. Sibiu has produced over 150 national champions of all ages. At least 60 gymnasts from the CSS gym have made the leap to the national Olympic teams.

Fourteen times, the title of the county’s best athlete has gone to gymnasts. For their exceptional results on the world stage, Claudia Presăcan (1996) and Sabina Cojocar (2000) were awarded the title of Honorary Citizen of Sibiu.

Hopes for 2008

When it comes to coaches, Sibiu also has nothing to complain about. At the Olympic training center in Deva, Professor Lucian Sandu—Octavian Belu’s “right hand”—helps prepare the senior national team. Thanks in part to him, Romania returned from this year’s Worlds with a silver medal. Recently, at the national junior team in Onești, Raluca Bugner and Ovidiu Șerban were recruited. They didn’t go alone—they brought two athletes with them: Steliana Nistor and Andra Stănescu, new hopes of Sibiu gymnastics. Still juniors, the two are part of the cycle preparing for the 2008 Olympics.

Because that is one of the secrets of gymnastics: it is always forward-looking. Preparation stretches over the long term—at least eight years. To all these results contributed the entire department: Dorina Opriș (head of department), Mihaela Stănuleț, Ovidiu Nistor, Andreea Baștea, and choreographer Mihaela Marcu—all under the guidance of “mentor” Nicolae Buzoianu.

Sibiu was also the hometown of Mircea Apolzan, a federation coach, and Adrian Sandu (Lucian Sandu’s brother), a coach with the men’s Olympic team.

Gymnasts train in the cold

The results of Sibiu gymnastics are inversely proportional to their training conditions. If you enter the gym on Independenței Street, you must first make sure you’re warmly dressed.

Even though it’s November, the radiators stubbornly remain cold. After just fifteen minutes standing in the gym, you already start to feel the chill. You wonder how dozens of little kids who have barely started school manage to endure three hours here every day. And that’s not all—the apparatus are outdated too.

“Every piece of equipment has its lifespan. And even if they physically hold up, they’re functionally obsolete. At each Olympics, new apparatus appear, and the previous ones are no longer used. Here, some of ours are decades old. Recently, we managed to bring some equipment from the Transylvania hall, which was unused anyway, but even those are outdated. They haven’t been used in international competitions for nearly ten years,” explains Professor Buzoianu.

Almost 100 medals

In her 11 years of competition, Mihaela Stănuleț won an impressive number of medals. She took part in nearly 16 domestic competitions and 33 international ones, including two World Championships, two European Championships, and one edition of the Olympic Games. Altogether, she collected 88 medals: 32 from domestic competitions (7 gold, 16 silver, 10 bronze), and 56 from international competitions (25 gold, 22 silver, 9 bronze): Worlds (one second place), Europeans (one third place), Balkan meets, and other international meets.

She “vaulted” over the judges’ table in Zagreb

Another amusing incident occurred in 1982, at the World Cup in Zagreb.

“I was competing on vault. I ran, performed the vault, but when I landed, because of the momentum, I couldn’t stop. I went right over to the judges’ table. I had to do back handsprings, so I wouldn’t knock their table over,” Mihaela Stănuleț recalls.

Sidebar: Guarded by Dogs

Although the barracks regime at Deva was a draconian one, Mihaela says that there were also moments she remembers with pleasure: “It was a hard period, but there were also beautiful moments. I remember that once, together with Melitta Rühn—another girl from Sibiu—we wanted to leave the training camp. We jumped the fence, but Coach Béla Károlyi realized it. He surrounded us with a pack of dogs and made us turn back,” the champion recalls, amused.

Ziarul de Sibiu, November 17, 2003

Appendix: The FIG Database

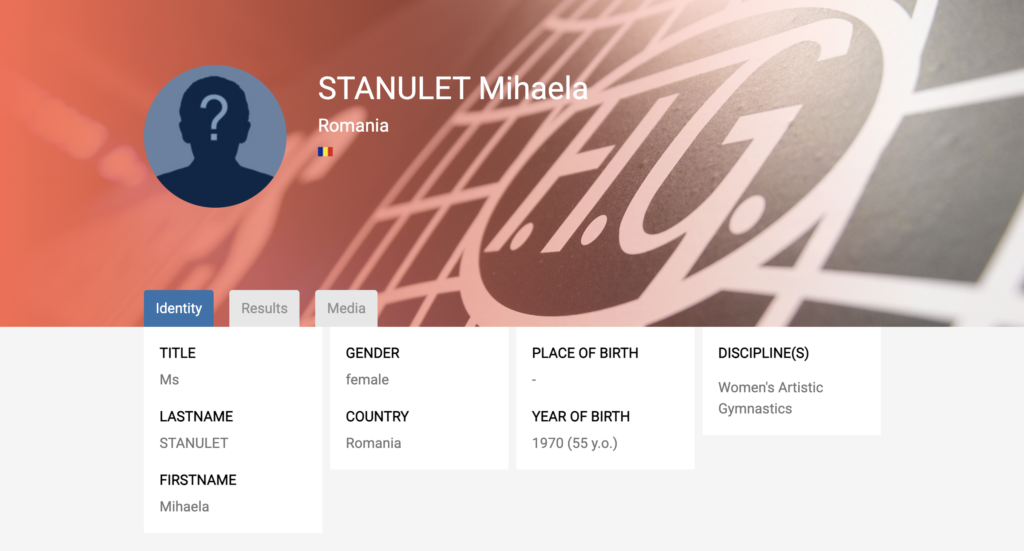

While the Romanian Gymnastics Federation aged Stănuleț to make her eligible for the 1981 World Championships, the FIG actually adjusted her age in the opposite direction, listing her birth year as 1970 in its athlete database.

More Interviews and Profiles