These three People’s Daily articles, spanning fourteen years from 1981 to 1995, trace the arc of Li Ning’s transformation from teenage gymnastics prodigy to business entrepreneur. Read together, they chart not only an individual career but a broader shift in Chinese sport and society, as the values and constraints of Mao-era athletic culture gradually gave way to new possibilities.

The first piece, published on August 30, 1981, introduces Li Ning at eighteen as a rising talent who had just won China’s first gold medal at the World University Games in Bucharest. Its narrative structure would become familiar in Chinese sports journalism: early discovery, setbacks overcome through ideological commitment, and moral guidance from exemplary teammates—in this case, Tong Fei. Li Ning appears here as a product of the state sports system at its ideological peak, his achievements framed primarily in terms of collective honor, discipline, and service to the nation rather than personal advancement.

By the end of the 1980s, both Li Ning’s career and China itself were entering a period of profound transition. Following the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, Deng Xiaoping initiated a series of economic reforms that gradually loosened the rigid command economy of the Mao years. Limited private enterprise and selective engagement with foreign capital were introduced, even as Communist Party control remained firmly in place. In the early 1980s, these reforms were tentative and uneven; by the early 1990s, they had begun to reshape everyday life, labor, and ambition, including elite sport.

It is against this backdrop that the second article, published in October 1990, finds Li Ning navigating unfamiliar terrain. Retired from gymnastics, he had joined Jianlibao, a state-owned sports drink manufacturer, to help develop China’s first indigenous sportswear brand. The piece reveals an athlete unsettled by the indignity of competing in foreign-branded clothing and determined to create a Chinese alternative. In a familiar literary trope about emerging markets, we witness Li Ning trying to cut across time and space in impossible ways. The writer even suggests that, for the retired gymnast, time itself has become three-dimensional.

The final piece, from March 1995, is an obituary for Li Ning’s mother. Qin Zhenmei, who died of cancer at fifty-four, is presented as the archetype of the self-sacrificing Chinese mother—a mother who went to great lengths to sew her son a training uniform and who promoted her son’s clothing brand from her deathbed. Yet the article is equally structured around Li Ning’s confession of filial failure—his admission that years of relentless work left him scarcely present at her bedside, sharing only three meals with her in her final year. Here, personal loss and moral regret serve to place commercial success within an acceptable moral framework, ensuring that entrepreneurial achievement does not appear to override traditional obligations.

Enjoy this longitudinal view of Li Ning’s biography, as refracted through the People’s Daily.

A New Star of Gymnastics — Li Ning

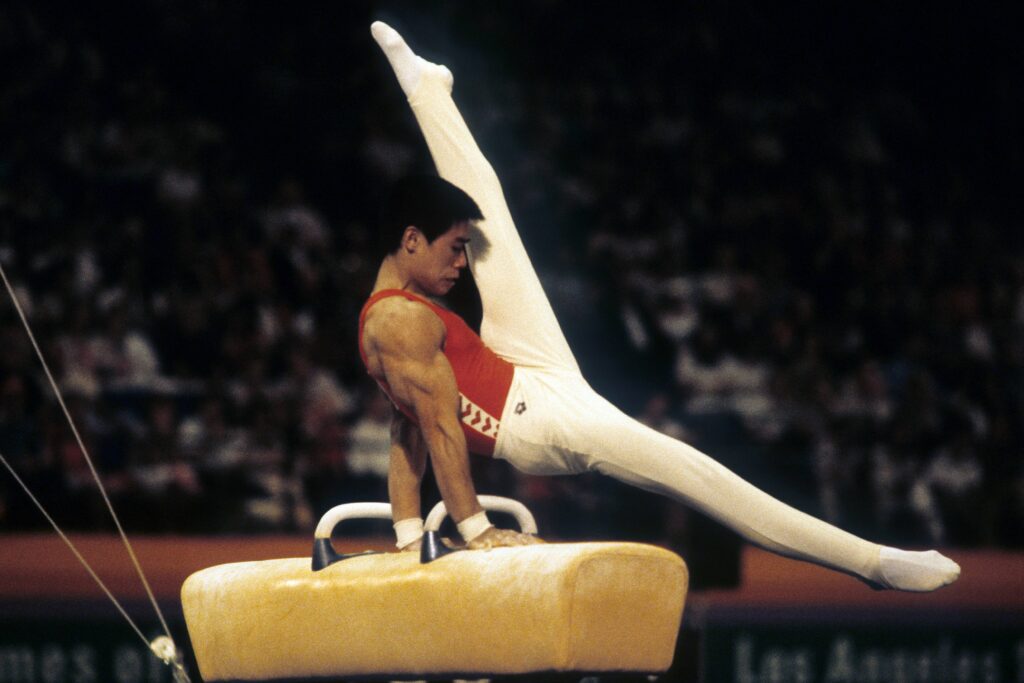

The floor exercise final at the 11th World University Games is underway, and it is now the turn of 18-year-old Chinese gymnast Li Ning. He opens with a breathtaking double somersault with a full 360-degree twist, followed by a piked double back somersault. He then innovatively brings the pommel horse Thomas flare onto the floor exercise, and finishes with another double somersault. Amid thunderous applause, Li Ning scores a 19.55, winning China’s first gold medal of the Games.

Li Ning was born into a family of educators in Liuzhou, Guangxi. At age eight, while attending Liuzhou Tuanjie Primary School, he saw members of the school gymnastics team practicing after class and longed to join them. Initially deemed too small, he practiced secretly on his own. By age ten, his ability had improved so much that he was noticed by Guangxi gymnastics coach Liang Wenjie. He trained diligently and progressed rapidly. In 1973, he won the floor exercise title and placed fourth on parallel bars at the National Junior Gymnastics Championships.

However, the road forward was not smooth. Three years later, he injured his arm while training on the parallel bars; before it fully healed, he twisted his foot. More discouraging still, he failed to place at the Fourth National Games. These setbacks gradually taught him that gymnastics requires not only courage, but also scientific training methods. To achieve superior technique, one must train relentlessly. His biggest weakness was his bent legs and flexed feet. Sharing a room with the outstanding gymnast Tong Fei, known for his elegant technique, Li learned from him. Tong helped him stretch and point his feet daily. After several years of hard training, Li Ning’s technique improved markedly.

At the National Gymnastics Zonal Championships held in June of last year, Li won first place on pommel horse and third on rings. In September, at the National Gymnastics Championships, he placed third in the all-around. Later that year, he competed in England, winning third on pommel horse. When he saw that Japanese gymnast Kajitani [Nobuyuki] won the title by just 0.1 points, he felt deeply dissatisfied. After returning to China, he raised his standards and trained even harder, mastering many high-difficulty skills recognized internationally. At this year’s national zonal championships in Kunming, he won the all-around title and four individual event titles. One month later, in Bucharest, he again shone brightly, winning three gold medals in floor exercise, pommel horse, and rings.

Yan Naihua

August 30, 1981

Li Ning Today

At a place named after the god of light on Tibet’s Nyenchen Tanglha Peak, in an extreme region closest to the sun, Li Ning received the “heavenly fire” kindled from beneath the sun and solemnly walked toward the flag of the 11th Asian Games.

This former “Prince of Gymnastics,” representing the athletes, went forth to receive the Asian Games torch. In China, was he not himself a torch, one that once lit up the sky of the sports world?!

Following Li Ning’s trail, “Jianlibao” made a phone call all the way to Tibet. They were told Li Ning was not available. But who knew that in the blink of an eye, Li Ning executed a “Thomas circle,” spinning back to the ancient town of Foshan. There, preparations were underway for the 1990 “Li Ning Cup” Asian Games gymnastics selection warm-up competition, which was opening the next morning. As the general supervisor and deputy chief judge of the event, he had to make an appearance.

With the dust of travel still upon him, he answered another phone call. It turned out that Chinese diplomats stationed abroad were waiting at “Jianlibao” to meet Li Ning. As the special assistant to the Jianlibao general manager, he needed to fulfill his hosting duties.

Traveling thousands of miles back and forth, experiencing three major events, all within 24 hours—people say Li Ning’s time is three-dimensional.

However, there are also times when he is defeated by time:

“Li Ning’s car broke down!”

It was a dark and stormy night when he drove his car, chasing time. Perhaps he was too tired—the car wouldn’t obey, crashing into a metasequoia tree by the roadside. By the time he called back to “Jianlibao,” it was the dead of night in the small town.

Knocking on the family door, the clock struck twice. The light was on, and Li Ning knew his mother was still waiting for him. “Mom, everything is just beginning; it’s tough. But don’t worry, when have I not pulled through?”

If he weren’t so demanding of himself, if he had placed the period at the peak of his life, he could have taken it easy. 106 gold medals, 14 of them world-class—this would have been enough for him to enjoy for a lifetime. Yet he chose a career starting from zero, joining “Jianlibao” to develop Chinese brand sportswear.

This was an unfamiliar path. What lay before him was no longer the “Li Ning flyaway” or “Li Ning parallel bars” that he handled with ease, but rather merchants, orders, capital, output value, taxes, profits, and so on.

With an increased workload, Li Ning took charge of a clothing company with over 500 employees in 8 months. From signing contracts with foreign merchants to importing equipment, training personnel, building factories, and producing products—everything raced ahead of time. Attentive visitors discovered that in his factory stood a sign: “Full Overtime.” No one knows when it was hung up or when its deadline might be. People only know that this enterprise is rushing to produce a gift to contribute to the Asian Games. Indeed! When tens of thousands of Asian Games torch relay runners rush from the four corners of the motherland toward the Asian Games venue, when Chinese and foreign journalists shuttle through the Asian Games competition zones, when Chinese athletes ascend the Asian Games award podium, people will see Li Ning’s name—as a sportswear brand, as his own value—and it belongs to China!

“It wasn’t like this before,” Li Ning said with chagrin. “What was I? When I went to win gold medals, I wore foreign brand sportswear, serving as a walking advertisement for foreign brand products.”

As early as 1980, before Li Ning was selected for the national team, his mother ran all over Nanning to purchase a presentable outfit for him. When he tried it on at home, it was enormously oversized. “Mom, we’re in sports, we care about physique, could you alter it for me?” But when he learned that his mother could only alter it by hand, stitch by stitch, he abandoned this request. From that time on, he felt that Chinese clothing was too monotonous, too rigid.

Ten years later, when “Jianlibao” general manager Li Jingwei planned with him to establish a sportswear factory, he became energized. He studied the history of clothing design and discovered: First, the world-renowned Lacoste sportswear, with its 80-year history, has endured precisely because of people’s worship of the two tennis giants of the same name wearing crocodile shirts; second, today’s mountaineering and down jackets are popular globally, also stemming from people’s yearning for mountaineering sports. It is precisely this yearning that inevitably attracts a consumer pursuit, driving a clothing trend. Not only that, but he also investigated the clothing industry in the Pearl River Delta and discovered that these manufacturers, whether in production technology or management level, were world-class. Yet the brand-name products they produced could only bear foreign labels, while they themselves earned only processing fees.

“We want to create Chinese brand sportswear,” Li Ning said.

This path was not easy. In Li Ning’s own words: “After leaving the sports world, I haven’t even had a few days to rest.” Indeed, opening his diary, time truly is three-dimensional: today still at “Jianlibao,” tomorrow arriving in Beijing; seeing him in the morning, by afternoon, he’s already in Hainan. Reading ten thousand books and traveling ten thousand miles truly became his compulsory courses.

Busy as he is, Li Ning still allocates some time for himself. Whenever he arrives at a place, in the gaps of time, he will quietly carry that bag of gymnastics shoes, leather hand guards, bandages, and other items that have followed him for years to the gymnastics room, to do a “cross” [iron cross hold], execute a double twist, or flip a somersault that’s high, floating, and light. Yes, having spun too long in the economic competition arena, sometimes he still yearns for that beautiful Thomas on the pommel horse.

Huang Aiqing, Zheng Qiqian

October 18, 1990

“The Gymnastics Prince” Remembers His Mother

The “Gymnastics Prince” Li Ning—who dominated the sports world ten years ago and has been active in the business world for the past decade—has in recent days been immersed in deep mourning for his mother.

On March 16, his mother, Qin Zhenmei, aged 54, passed away from illness at the Beijing Cancer Hospital. In a small rented farmhouse courtyard in the southeastern outskirts of the capital, Li Ning set up a modest memorial hall. Speaking with several sports reporters who came to pay their respects, he said:

“My mother was a typical Chinese working woman. She had been a teacher and lived her whole life with diligence and thrift. She worked tirelessly to raise the three of us siblings. Yet when we grew up, we were constantly running around pursuing our careers and failed to take proper care of her.”

As he spoke, Li Ning’s eyes reddened and filled with tears.

“When I was a child, our family lived very frugally. I still clearly remember the day I left Liuzhou to join the regional gymnastics training team in Nanning. My mother dyed a piece of cotton cloth and stayed up all night sewing me a uniform that looked like a green military outfit. When she saw me off the next morning, I was dressed in brand-new clothes, while my older brother, beside her, wore clothes full of patches. Seeing that scene, no words were needed—my mother’s deep love was forever imprinted on my heart.”

“Later, I became a world champion and an Olympic champion. After retiring, I joined Jianlibao and then founded the Li Ning Company. Our financial circumstances improved more and more. But my mother never wanted to stay in Beijing or Guangdong to enjoy a comfortable life. She missed her hometown and always returned to Guangxi. Whenever neighbors or villagers ran into difficulties, she would help them generously, never begrudging money. She often reminded me of the old saying that wealth cannot corrupt one’s principles, and poverty cannot shake one’s resolve. After she fell ill, in order to lessen the burden on us children, she endured her pain and always told us she was in good health, urging us not to worry and to focus on our work outside. She constantly kept my career in mind and did everything she could to help the Li Ning Company prosper. Even just days before her death, she was still contacting friends at local primary and secondary schools to help promote Li Ning-brand school uniforms.”

“These past few years, I’ve been busy from morning till night and never took the time to be properly with my mother. Last year, I only managed to share three meals with her. I failed in my filial duty. When I think of that, I feel such regret and such sorrow.”

Li Ning’s mother passed away quietly, leaving no regrets. She raised an outstanding sports talent for the nation. Her life was ordinary and simple, yet she left her children and future generations a legacy of traditional Chinese virtues worthy of pride and remembrance.

Liu Xiaoming

March 20, 1995

More Interviews & Profiles