When Béla Károlyi defected to the United States in 1981, he carried with him not only his reputation as Nadia Comăneci’s coach but also Romania’s secrets. Speaking to the New York Times in December 1981, after an age scandal erupted at the World Championships in Moscow, Károlyi made a stunning allegation: three members of the Romanian women’s team competed in Moscow despite failing to meet the 15-and-over age requirement. They were Lavinia Agache, who he said was 13 years old; Christina Elena Grigoraș, also 13; and Mihaela Stănuleț, 14.

It would have been easy to dismiss these claims as the bitter accusations of a defector. But Károlyi was telling the truth. Subsequent research has confirmed that Mihaela Stănuleț was born in 1967, making her 14 at the 1981 World Championships. Lavinia Agache was born in 1968 and was indeed 13 years old. And, as we’ll see in the archival record below, Cristina Elena Grigoraș, the young star who had dazzled audiences with her European Championship performance earlier that year, was also born in 1968—not 1966, as her official documents claimed.

That means she was only twelve years old when she competed at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, well below the minimum age requirement of fourteen. Romania’s silver-medal team performance thus relied, in part, on the participation of an underage athlete competing under an incorrect birthdate.

The Paper Trail

The documentary evidence tells a story that official birthdates cannot obscure. In April 1978, Romanian newspapers covered the Republican School Championships in artistic gymnastics, where young athletes competed in age-defined categories. Category IV—for girls “ages 8–10″—saw a thrilling finish: Cristina Grigoraș won with 37.55 points, edging out her teammate Lavinia Agache by just one-tenth of a point. Both represented the Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej gymnastics program. According to her age category, Grigoraș was at most 10 years old.

Less than a year later, in March 1979, these same young gymnasts had captured the attention of the Romanian sports press. A Scînteia Tineretului reporter, observing a junior selection competition, marveled that “the leading figures of this generation are not gymnasts from the cohort immediately following Nadia Comăneci and Teodora Ungureanu, but rather girls aged 11–12.” Among this remarkable group, one stood out. “[T]he winner, Cristina Grigoraș (Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej), clearly distinguished herself from the rest,” earning the day’s highest score of 36.50 points.

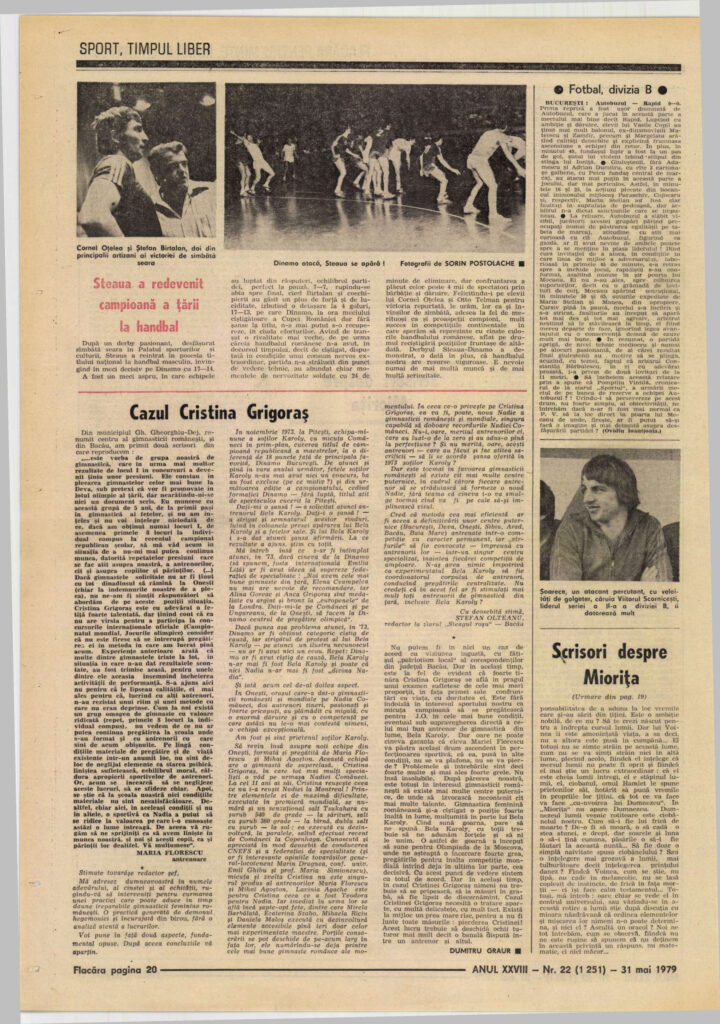

That spring, Grigoraș became the subject of national attention—and controversy. In May 1979, Flacăra magazine published “The Case of Cristina Grigoraș,” examining a dispute over where the young prodigy should train. The article featured a passionate defense by journalist Ștefan Olteanu, who wrote: “At age 11, Cristina achieves what Nadia did not achieve at that age.” He catalogued her arsenal of groundbreaking skills: “a sensational Tsukahara with a 540-degree twist on vault; a 360-degree twisting salto on beam; and a double salto with a twist on floor.”

The article painted a vivid picture of an extraordinary talent. But it also did something else: it clearly identified Grigoraș as 11 years old in May 1979. With her February birthday, the math was simple—she was born in 1968, not 1966.

The Olympic Alteration

When Romania’s Olympic delegation was announced for the Moscow Games in July 1980, the official roster listed Cristina Elena Grigoraș with a birthdate of February 11, 1966. According to these documents, she had just turned 14—exactly the minimum age required for Olympic competition. But given the newspaper trail from 1978 and 1979, she should have been 12. Somewhere along the line, two years had been tacked onto her age.

| Year | Competition Age | Actual Age |

| 1978 | Category IV (ages 8-10) | 10 |

| 1979 | 11 | 11 |

| 1980 | 14 | 12 |

| 1981 | 15 | 13 |

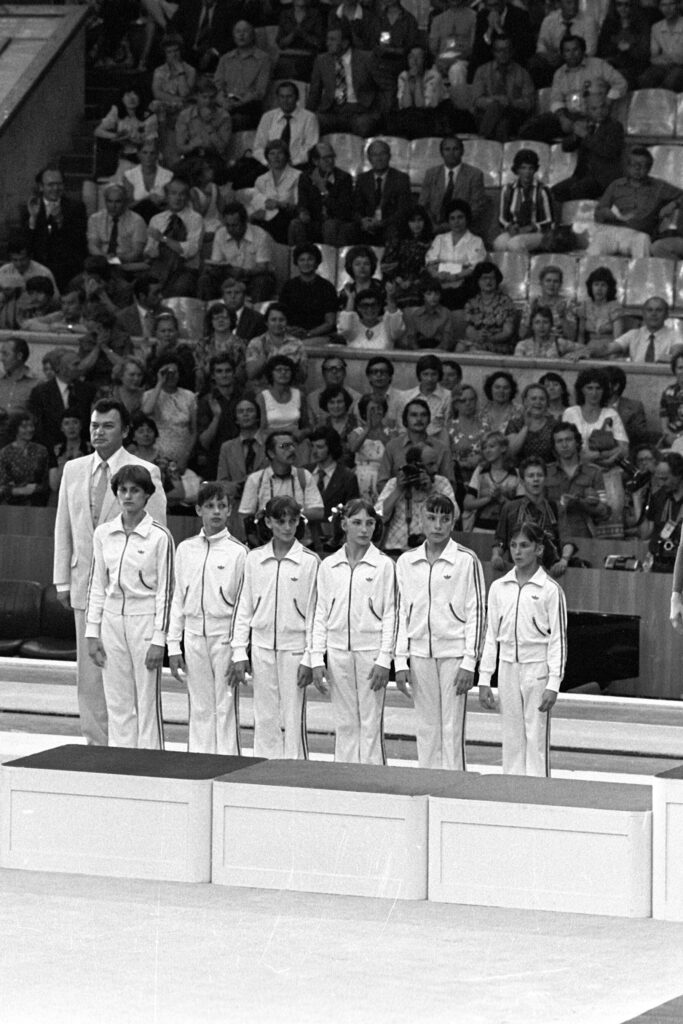

In Moscow, Grigoraș was initially listed as an alternate. But when the competition began, coach Béla Károlyi made a last-minute decision to include her in the lineup. As Sportul reported: “At the last moment, coach Béla Károlyi entrusted a place to the very young Cristina Grigoraș, making her debut on the national team at her first major competition.”

It was a gamble that paid off, especially during the optionals. On floor exercise, she earned 9.80. Then came vault, where she launched herself with the explosive power that had already earned her perfect 10s back home. The judges awarded 9.95—”one of the highest scores of the entire Olympics,” Sportul marveled, calling it “a major success for such a young athlete.”

Flacăra Iaşului captured the electricity of the moment: “A pleasant surprise came from the team’s debutant, Cristina-Elena Grigoraș, who received 9.95, one of the highest scores of the entire Olympics—a major success for such a young athlete.”

When the dust settled, Romania stood on the podium with silver medals, finishing second behind the Soviet Union. Grigoraș had been instrumental to that success. But if she had truly been born in 1968, as the documentary evidence suggests, she would have been only 12 years old—a child competing on the Olympic stage.

European Champion at Thirteen

By early 1981, with the age minimum raised to 15, Grigoraș should have been ineligible for senior international competition. According to the timeline in the newspapers, she was just 13. But according to her official documents, she was now 15 and eligible for senior competitions.

That spring, she traveled to Madrid for the European Championships—her first major individual competition. Nadia Comăneci, the nine-time European champion, was absent, and the pre-competition atmosphere was tense. As Sportul reported: “At the pre-competition press conferences and in discussions among specialists, several names were repeatedly mentioned among the favorites: Maxi Gnauck, Olympic champion on uneven bars in Moscow; Emilia Eberle, double silver medalist at the same Olympics (uneven bars and team); and Rodica Dunca, one of the most consistent gymnasts in the world. Yet many observers—following her rapid rise in recent months—also pointed to Cristina Grigoraș as a serious medal contender.”

She did not disappoint. During the all-around, Grigoraș demonstrated what Sportul called “impressive sporting maturity.” She began on balance beam, opening the entire rotation—a position of maximum pressure. Her routine included “a highly precise execution of a difficult element—a forward salto with a 180-degree turn, an element that belongs to her and bears her name—earning a 9.65.”

On floor exercise, she received 9.60, though the Romanian delegation protested the score. On vault, she was magnificent. Her second attempt was, as the newspaper described it, “textbook—powerful run, high flight, a perfectly executed Tsukahara, and a flawless landing. The judges had no choice but to award 9.90, the highest vault score and the second-highest score in the all-around.”

On uneven bars, she earned 9.80, securing second place in the all-around behind East Germany’s Maxi Gnauck—a fully deserved reward, the Romanian press insisted.

But she was just getting started. During the event finals the next day, Grigoraș competed on all four events. On vault, she “executed both vaults very well, achieving a 9.70 average, which—combined with her 9.90 from the all-around—produced an excellent total of 19.600, earning her the gold medal.”

Following in Nadia Comăneci’s footsteps, she was Romania’s second female gymnast to win a European title. And she was just 13 years old (but 15 on paper).

“To our great joy, the first European champion of the day was Cristina Grigoraș,” Sportul reported with evident pride. On uneven bars, competing first and at a disadvantage, she still earned a silver medal, tied with Soviet gymnast Alla Misnik. On floor exercise, closing out the championships, she won bronze with a 9.65.

The reception back in Romania was euphoric. When the team landed at Otopeni airport, Grigoraș could not “hide her joy—and rightly so: this beautiful 15-year-old girl defeated the absolute champion Maxi Gnauck on vault, being the only gymnast in Madrid who can boast such an achievement.”

Flacăra, the same magazine that said she was 11 in 1979, proclaimed: “In both the all-around competition and the apparatus finals, Cristina Grigoraș demonstrated exceptional talent and, beyond that, remarkable sporting maturity, winning four medals, including the gold medal on vault. In doing so, she continued the line of successes inaugurated in Romania by Nadia Comăneci.”

International experts were effusive in their praise. Margot Dietz, senior technical consultant for the International Gymnastics Federation from East Germany, told Sportul: “I truly enjoyed noting that Nadia’s absence was felt only to a small degree, and that Cristina Grigoraș and Rodica Dunca demonstrated the qualities of great gymnasts. I have no doubt that they will have an important say in future international competitions… Cristina Grigoraș was a revelation for many and will probably be Romania’s great champion of tomorrow.”

Nikola Hadjiev, president of the Bulgarian Gymnastics Federation, was even more enthusiastic: “In Cristina Grigoraș, you have a gymnast who will soon be able to replace your great athlete Nadia Comăneci. Here in Madrid, young Cristina performed with great personality and style, and I foresee a fine future for her.”

The Truth Emerges

Six months later, at the World Championships in Moscow in November 1981, Grigoraș competed again. She finished fifth in the all-around, fifth on uneven bars, and helped Romania to a fourth-place team finish. It was a respectable showing, though not the medal performance many had hoped for after Madrid.

Shortly after, when the age scandal broke, and Károlyi made his allegations to the New York Times, the Romanian coaching staff vehemently denied the charges. Maria Simionescu, the new national coach and a member of the women’s technical committee, insisted in an interview with Sportul: “All of the members of the team that went to Moscow traveled under a collective passport that listed their ages, which was listed in the foreign ministry in Bucharest, on the basis of their birth certificates. This document was presented to and accepted by a verification committee of the international federation in Moscow, a few days before the beginning of the championship.”

She was technically correct; the passports had been accepted. But Károlyi’s point was that the passports themselves were fraudulent, and the birthdates falsified.

The Times article captured the broader context of the controversy. American gymnasts Julianne McNamara and Tracee Talavera had also alleged that Soviet gymnast Olga Bicherova, the new world champion, was underage. “Bicherova’s good, but she’s not 15,” 15-year-old Talavera said. “You only have to look at her.” McNamara added, “When Agache was in the American Cup last March, she told me she was 13. Now she’s 15.”

Age falsification was simply another dimension of a sport in crisis—widely suspected, openly discussed, yet rarely substantiated beyond impression and accusation.

In this case, however, the question does not rest on conjecture or rival testimony. From our vantage point in 2026, the documentary record is unusually clear.

The Skill That Will Be Remembered

The public record in the archive shows that she was placed into senior competition two years before she should have been eligible. The evidence is consistent across sources: the age-category competitions of 1978, the explicit identification of her as eleven years old in 1979, and Béla Károlyi’s 1981 testimony all point to the same conclusion. The February 1966 birthdate attached to her international career was a fabrication. Contemporaneous reporting suggests that her true birth year was 1968.

Which means she was twelve years old at the Moscow Olympics, competing two years below the minimum age requirement. She was thirteen at the European Championships in Madrid, competing two years below the minimum age and becoming Romania’s second-ever European champion. It was a performance celebrated as the emergence of a worthy successor to Nadia Comăneci, yet it rested on an identity invented by the adults in power.

Those medals and titles cannot be separated from that context. But they cannot be reduced to that context either.

What often gets lost in discussions of falsification is the gymnast’s talent. Grigoraș’s gymnastics was not just impressive for her age; it was exceptional by any standard. When it comes to her physical abilities, the historical record leaves little ambiguity. Before she reached her teens, she was already performing elements of a difficulty level rarely seen in senior competition—let alone in junior ranks—including a skill that would later be entered into the Code of Points under her name.

The “Grigoraș,” a front tuck with a half twist on balance beam, demonstrates her willingness to attempt elements others avoided—and continue to avoid. Decades later, it remains among the most difficult skills on the apparatus.

In a way, that little box in the Code encapsulates Grigoraș’s legacy.

She pushed the sport’s difficulty forward, even as the adults in power pushed her age forward.

References

Primary Sources

Newspaper and Magazine Articles (1978-1981)

1978

Scânteia Tineretului, April 14, 1978 (nr. 8987). “Spectacle and Surprises at the School Gymnastics Championships.”

Sportul, April 14, 1978 (nr. 8835). “Final of the Republican School Championship in Artistic Gymnastics.”

Scânteia Tineretului, April 15, 1978 (nr. 8988). “Republican School Gymnastics Competition Concludes Before a Large Crowd.”

Sportul, June 28, 1978 (nr. 8897). “We May Hope That Great Performances Will Not Be Long in Coming.”

1979

Scânteia Tineretului, March 13, 1979 (nr. 9269). “A New Golden Generation.”

Sportul, March 13, 1979 (nr. 9115). “The Changing of the Guard in Our Women’s Gymnastics Is Taking Shape.”

Sportul, April 10, 1979 (nr. 9139). “The Onești Gymnasts Dominated the School-Profile Championships.”

Viața Studențească, May 16, 1979 (nr. 20). “A School of Bravery.”

Sportul, May 19, 1979 (nr. 9171). “Victories at the European Championships in Copenhagen.”

Scînteia, May 26, 1979 (nr. 11433). “Authentic Talents at School Competitions.”

Flacăra, May 31, 1979 (nr. 22). “The Case of Cristina Grigoraș.”

Sportul, June 19, 1979 (nr. 9197). “Romania Defeats East Germany in Junior Women’s Gymnastics.”

Scînteia, December 16, 1979 (nr. 11607). “In Bacău: Fine Performances by Young Gymnasts in the ‘Romania Cup.'”

Sportul, December 18, 1979 (nr. 9351). “The Onești Gymnastics High School and the Sibiu School Sports Club Teams Win the ‘Romania Cup’ in Gymnastics.”

Sportul, December 24, 1979 (nr. 9356). “Balkan Junior Championships Dominated by Romanian Gymnasts.”

Sportul, December 25, 1979 (nr. 9357). “Tomorrow’s Champions of Our Gymnastics Promise Spectacular Successes.”

1980

Sportul, June 19, 1980 (nr. 9504). “Important Assets for Our Gymnasts in View of Repeating Major Successes.”

Scînteia, July 13, 1980 (nr. 11786). “Preparations for the Olympic Games” and “Romania’s Teams for the 22nd Edition of the Olympic Games in Moscow.”

Sportul, July 21, 1980 (nr. 9531). “Women’s Artistic Gymnastics — Team Event, Compulsory Exercises.”

Flacăra Iaşului, July 22, 1980 (nr. 10512). “In gymnastics, Nadia Comăneci debuted with a perfect 10.”

Sportul, July 22, 1980 (nr. 9532). “A Tight Battle for First Place in the Women’s Team Gymnastics Competition.”

Sportul, July 24, 1980 (nr. 9534). “Romania’s Women’s Team Wins the Silver Medal.”

Steaua Roşie, July 24, 1980 (nr. 174). “Moscow Olympic Games.”

Scînteia Tineretului, December 8, 1980 (nr. 9810). “Romanian Women’s Gymnastics Confirms Once Again Its High International Value.”

1981

Flacăra, May 7, 1981 (nr. 19). “Cristina Grigoraș – A European Championship Gold Medal.”

Sportul, May 4, 1981 (nr. 9770). “Remarkable Balance Sheet for Our Athletes: 1 Gold, 2 Silver and 2 Bronze Medals.”

Sportul, May 5, 1981 (nr. 9771). “Cristina Grigoraș and Rodica Dunca Honored the Prestige of the Romanian School of Gymnastics.”

Sportul, May 6, 1981 (nr. 9772). “Showers of Medals — Bouquets of Flowers!”

Sportul, May 7, 1981 (nr. 9773). “Glorious Assessments of Our Gymnasts’ Performances.”

Flacăra, November 19, 1981 (nr. 47). “Three Days Until the Start of the World Gymnastics Championships.”

Magazin, November 21, 1981 (nr. 1259). “World Gymnastics Championships.”

Sportul, November 23, 1981 (nr. 9944). “400 Athletes from 37 Countries at the Start of the Great Competition.”

Sportul, November 25, 1981 (nr. 9946). “After the compulsory routines, the Romanian women’s team, with three debutants, was in 4th place.”

Sportul, November 27, 1981 (nr. 9948). “In the women’s competition, the top three teams.”

Sportul, November 28, 1981 (nr. 9949). “Thrilling competitions of a very high technical level.”

Sportul, November 30, 1981 (nr. 9950). “The World Gymnastics Championships Have Concluded.”

Amdur, Neil. “Rift Over Underage Gymnasts.” New York Times, December 7, 1981.

Secondary Sources

“2003: A profile of Mihaela Stănuleț.” Gymnastics History, https://www.gymnastics-history.com/2025/12/2003-a-profile-of-mihaela-stanulet-the-olympic-champion-is-freezing-at-the-sports-school-club/

“2001: A profile of Lavinia Agache.” Gymnastics History, https://www.gymnastics-history.com/2025/12/2001-a-profile-of-lavinia-agache-time-on-her-side/

Note: To my knowledge, Cristina Elena Grigoraș has never publicly stated that she was born in 1968. Nonetheless, the contemporaneous documentary evidence strongly points to 1968 as her actual year of birth.

The Case of Cristina Grigoraș

From the city of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej (Onești)—a renowned center of Romanian gymnastics—and from Bacău, we received two letters, from which we reproduce the following:

Letter 1 (Coach Maria Florescu)

“…It concerns our gymnastics group, which, after achieving multiple first-place results in competitions, has become the target of pressure. This pressure consists of the departure of our best gymnasts to Deva, under the pretext that they will be promoted to the country’s Olympic squad, but without showing us any written document.

I have worked with this group for five years, from the girls’ first steps in gymnastics, and I have not understood—and will never understand—how it is possible that, after we achieved only first places, and even the first eight places in the all-around at the recent Republican School Championships, I should now find myself in the situation of being unable to continue my work, because of repeated pressures placed on us—the coaches—as well as on the children and their parents.

(…)

If the requested gymnasts had not insisted with all their might on remaining in Onești (even when we ourselves urged them to leave), we would not have felt responsible to address the situation from this standpoint.

Cristina Grigoraș truly is a very talented little girl. But given that she is not yet of age to participate in official international competitions (World Championships, Olympic Games), I do not consider it natural to interrupt her preparation in the method under which we have worked up to now.

Previous experience shows that many gymnasts taken into the national squad, when they did not produce the expected results, were sent back home, and for some of them, this meant the end of elite sport. This happened not because they lacked qualities, but especially because, working with different coaches, they did not withstand a tempo and a method to which they were not accustomed.

Since we have here a cohesive group of gymnasts of high value (I repeat: the first eight places in the all-around), we do not see why they could not continue their training at the school where they were formed, with the coaches to whom they are already accustomed.

Beyond material training and living conditions in a given place, factors such as psychological state, inner calm, moral balance, and the warmth of the athletes’ relationship with their coaches are by no means negligible. And yet now there are attempts to ignore these things—indeed, to defy them.

Moreover, it is known that at our school, the material conditions are not unsatisfactory. After all, here, in these very conditions and not others, an athlete like Nadia was able to reach the value the whole world knows today.

Therefore, we ask you to support us so that we may have peace in our work, both we and these children, and their parents as well. Thank you.”

MARIA FLORESCU, coach

★ ★ ★

Letter 2 (Ștefan Olteanu, “Steagul Roșu,” Bacău)

“Dear Comrade Editor-in-Chief,

I address you in the name of truth, honesty, and fairness, asking you to intervene to put an end to a practice that can, over time, bring irreparable harm to Romanian women’s gymnastics—a practice generated by the demon of hegemony and encouraged from offices, without an attentive analysis of the facts.

I will place before you two fundamentally opposed aspects. After that, the conclusions are yours.

In November 1973, at Pitești, the ‘miracle team’ of the Károlyi couple, with little Comăneci in the foreground, won the republican masters’ championship title by 18 points over the main favorite, Dinamo Bucharest. From then until the summer of the following year, the Károlyis’ girls had no competitions; they were even excluded (for what reason?) from the next edition of the championship, yielding to Dinamo—without a fight—the title so spectacularly won at Pitești.

‘Give me a chance!’ coach Béla Károlyi asked then. ‘Give him a chance!’ the undersigned also cried out, defending Béla Károlyi and his girls in the press. And Béla Károlyi was given that chance. Where he arrived, we all know.

But I ask myself what would have happened in 1973 if someone from Dinamo (let us say the former international gymnast Emilia Liță) had suggested to the federation:

‘We have the best gymnasts in the country—Elena Ceampelea needs no recommendation, and Alina Goreac and Anca Grigoraș are European medalists. Give us Comăneci and Ungureanu from Onești so we can make Dinamo the Olympic preparation center.’

If that had been the framing, then, in 1973, Dinamo would categorically have prevailed, and Béla Károlyi’s protest—then an unknown—would have had no echo. I repeat: Dinamo would have prevailed; Béla Károlyi would no longer have been Béla Károlyi, and perhaps Nadia would never have become ‘divine Nadia.’

And now the second aspect.

In Onești, the city that gave Romanian and world gymnastics Nadia Comăneci, two young, passionate, and very capable coaches have painstakingly molded, with enormous devotion and competence, an exceptional team. I have been and remain a friend of the Károlyi couple.

But let me return to the new Onești team, formed and trained by Maria Florescu and Mihai Ágoston. This team has a gymnast of super-class: Cristina Grigoraș, whom more and more specialists already see as Nadia’s successor.

At age 11, Cristina achieves what Nadia did not achieve at that age. Among her maximum-difficulty elements—some performed as world premières—are a sensational Tsukahara with a 540-degree twist on vault; a 360-degree twisting salto on beam; and a double salto with a twist on floor. On uneven bars, she performs with ease the salto that Comăneci recently introduced at Copenhagen.

Cristina is not the only product of Florescu and Ágoston. Lavinia Agache is for Cristina what Teodora was for Nadia. Immediately behind them are another seven or eight girls—among them Mirela Barbălată, Ecaterina Szabó, Mihaela Rîciu, and Daniela Maloș—who execute with ease elements that until yesterday were accessible only to the most experienced masters. The doors of recognition can open for them already; they are among the best Romanian gymnasts of the moment.

As for Cristina Grigoraș, she may become the new Nadia of Romanian and world gymnastics—the only one capable of breaking Nadia Comăneci’s records.

Is this not the merit of her coaches, who took her from zero and brought her to this level? And do these coaches—who have made and continue to make so many sacrifices—not deserve the chance granted in 1973 to the Károlyis?

But it is precisely in the interest of Romanian gymnastics to have as many strong centers as possible, where every coach strives to form a new Nadia without fear that someone will snatch her away just when the dream is about to come true.

I believe the most efficient method would be to consolidate several strong centers (Bucharest, Deva, Onești, Sibiu, Arad, Bacău, Baia Mare) engaged in permanent competition, and for the ‘peaks’ to be called up—together with their coaches—to a single specialized center before each major competition.

I would have nothing against the experienced Béla Károlyi serving as coordinator of the coaching body, directing the centralized preparations. Would this not stimulate all coaches in the country—including Béla Károlyi himself?

With great respect,

ȘTEFAN OLTEANU, editor at ‘Steagul Roșu’—Bacău”

★ ★ ★

Editorial Note (Dumitru Graur)

We cannot, in any case, agree with the narrow vision, with the overt “local patriotism” of the correspondents from Bacău County. But at the same time, it is equally evident that the very young Cristina Grigoraș stands at the threshold of a psychological ordeal of the greatest proportions, facing her first real confrontation with life and its hardness.

It is undoubtedly in the interest of our sport that the little champion be prepared for the Olympic Games under the best conditions—possibly under the direct supervision of the best gymnastics coach in the world, Béla Károlyi. But can anyone guarantee that Maria Florescu’s pupil will maintain the same upward path of athletic performance, that, placed in different conditions, she will not lose her way?

The problems and questions are therefore numerous—and serious—but not insoluble.

In our view, it is nevertheless in the interest of Romanian gymnastics to have several powerful centers from which many talents continuously emerge. Romanian women’s gymnastics has won a very high position in the world, thanks in part to Béla Károlyi. When the trumpet sounds, Béla Károlyi seems to tell us, we must all gather our forces and unite them. Such a trumpet has begun to sound for the Moscow Olympiad, where a very hard trial awaits us; preparations have entered their final, decisive phase. We completely agree with this point of view.

But at the same time, in Cristina Grigoraș’s case, no one should rush, take hasty measures, or lack discernment. Her case requires special handling, with great delicacy and tact. The risk is too great not to take every measure: the loss of Cristina. This must open everyone’s eyes more than a banal dispute between one coach and another.

DUMITRU GRAUR ■

Flacăra, May 31, 1979

More on Age