In October 2002, more than two decades after Romania’s women’s gymnastics team won gold in Fort Worth, Rodica Dunca broke a long silence. Speaking to Pro Sport, the former international gymnast described daily life inside the Deva training camp not as a center of excellence, but as a place of hunger, surveillance, fear, and physical coercion. Her testimony names teammates whose faces became global symbols of grace—Nadia Comăneci, Melitta Rühn, Emilia Eberle (Trudi Kollar), Dumitrița Turner, Teodora Ungureanu—and places their medals alongside scenes of beatings, escapes intercepted by the Securitate, and bodies pushed beyond collapse. What Dunca recounts is not a single shocking incident, but a system: one in which control over food, water, movement, pain, and obedience defined her adolescence.

Like Eberhard Gienger, Dunca recalls being given an obscene number of pills and injections; unlike Gienger—who admitted to returning many of them to the pharmacy—she was compelled to take everything she was given. Dunca does not identify the substances involved, making it impossible to determine whether any appeared on the IOC’s banned list. She was competing, moreover, in an era when the FIG did not conduct systematic testing, and when the reliability of the drug controls at the 1980 Olympics remains questionable at best. Even had prohibited substances been involved, a positive test would have been unlikely.

Yet the absence of a positive test is not the absence of a problem. Dunca’s account instead directs attention to the medical regime under which Romanian gymnasts trained and competed. The forced ingestion of dozens of unidentified tablets each day, the routine administration of injections associated with prolonged amenorrhea, and the later emergence of drug dependence—all point to a system of non-therapeutic, coercive medical management that regulated young athletes’ bodies for performance, not health.

Set against official narratives of discipline, sacrifice, and triumph—most famously associated with Béla Károlyi—Dunca’s interview exposes the cost hidden behind the perfect smiles and historic scores. It is a reminder that Romania’s golden era in women’s gymnastics was built not only on innovation and talent, but also on practices that blurred the line between training and punishment, medicine and control, excellence and abuse.

Below, you’ll find a translation of ProSport‘s interview with Dunca from October 26, 2002.

“At Deva, It Was a Concentration Camp”

The gymnasts were strictly guarded—even when they went to the toilet—because they were not allowed to drink water. Still, they tricked the coaches and quenched their thirst from the toilet bowl.

Rodica, it’s said that Béla Károlyi had harsh training methods.

“I think ‘harsh’ is putting it mildly, given that if we got away with only a beating, we were satisfied. That’s even though on some days we were hit so badly that blood streamed from our noses. Hunger was our constant enemy.”

But what frightened you the most about Károlyi? Was there a specific incident?

“It was toward the end of an ordinary training day—nine hours of practice. We had reached physical conditioning. That meant climbing the rope in an L-sit position. I climbed up and down twice, and Béla shouted at us to do it once more. Melitta Ruhn managed only to reach the top. At some point she couldn’t go on anymore and fell from up there.”

How did the coach react?

“At that moment, he said nothing. Melitta lay unconscious on the floor; the ambulance came and took her to the hospital. She was hospitalized for about two weeks. But when she returned, Károlyi gathered us all in the gym and told her: ‘If you roll your eyes in front of us one more time, goodbye. You’re going home.’ We were stunned.”

And yet you endured the Károlyi regime?

“No. You could say it was a concentration camp. Or a prison. We were forced to stay there, because we escaped from the training camp several times.”

How?

“Around 1980 or 1981. Károlyi hadn’t yet fled to America. We were exhausted; we didn’t know what else to do. One evening, Melitta, Teodora, and I decided to escape. We climbed out the window, went to the train station, and took a train toward Baia Mare. But in Dej, the Securitate caught us and brought us back.”

Did Nadia want to run away with you?

“We hadn’t asked her, but strangely enough, by morning, she wanted to do the same thing. She couldn’t get out and hid in an unused toilet in the training hall. She stayed there for three days. The coaches asked us if we knew anything about her.”

And what were the consequences?

“Károlyi nailed the windows shut, and the Securitate threatened us that if we ran away again, our parents would suffer.”

“We Urinated with the Door Open”

There were probably other reasons as well that pushed you toward such things.

“Hunger put us in extreme situations almost all the time. And probably the methods they used to keep us away from food made us desperate.”

What methods were used?

“I remember that in 1979, before the World Championships in Fort Worth, Nadia had a few extra kilograms. We were in Germany at a training camp. Géza Pozsár, the choreographer, and Béla Károlyi slept in the same room with us. The toilet was right outside the door. When we needed to go, we had to urinate with the door open.”

Why?

“They were afraid we might drink water. But we would go into the bathroom, relieve ourselves, and not flush. We would climb up on the toilet and, using a glass hidden there, we would take water from the tank above. That’s how we drank our fill.”

But you could have gotten sick.

“It didn’t matter anymore.”

And when you showered?

“The same thing happened. We were guarded and weren’t allowed to lift our heads, in case we might swallow water.”

“Twice I Was Full”

What did you eat before competitions?

“In the morning, one slice of salami, two walnuts, and a glass of milk. In the evening, the same menu, but without the walnuts.”

Did you ever eat until you were full?

“Only twice, during all the time I was a gymnast.”

Only that?

“Well… it happened one more time. We were at a demonstration in Spain. We went out of the hotel, and somehow the coaches weren’t around. A few meters from the building, there was a strawberry field. We all rushed in there like termites and ate our fill. It came out afterward, because the owner made a scene at the hotel.”

“An Injection with Hormones, Two Years Without a Period”

Did you ever have serious health problems?

“Very often. Broken legs, my shoulder, and others. I remember that when we got our period, the nurse would take us to the medical office and give us an injection. It may have contained hormones, because after that, I didn’t have my period for almost two years. The same thing happened to the other girls.”

What pills were you taking?

“We weren’t really taking them—they were almost forced down our throats. The nurse stood next to each of us to make sure they were swallowed. In the morning there were 14 tablets, at noon 20 and four sachets of powdered substances, and in the evening 10. We never knew what kind of pills they were.”

And after you quit gymnastics?

“After I quit, I had problems.”

What kind of problems?

“I had become dependent and had to keep buying them myself for another year. The pharmacist would cross himself when he saw how much I could swallow.”

So in the end, you found out what kind of medications they were?

“Yes, but I no longer remember what they were called. Now it doesn’t matter anymore.”

Suffering Behind the Smile

The supremacy of Romanian women’s gymnastics on the world stage has deep roots. The tone of performance was set during the generation of Nadia Comăneci, beginning in the mid-1970s. From the training camps at Onești and later Deva, the gymnasts periodically went out to competitions, briefly leaving behind a communist and impoverished country. Each time, before foreign audiences, the girls coming from Romania had the strength to smile, with pieces of metal hanging from their necks.

Only behind such album-like photographs were things hidden that defy the imagination. If someone had captured on film images from the girls’ lives in training camp, that film would have shocked viewers to tears. It would have shocked somewhat more than Nadia’s perfect 10 received in the arena in Montréal. Or, if the film had been broadcast before her routine, she probably would have received, instead of a 10, a quarter from America and the right to live in a free world.

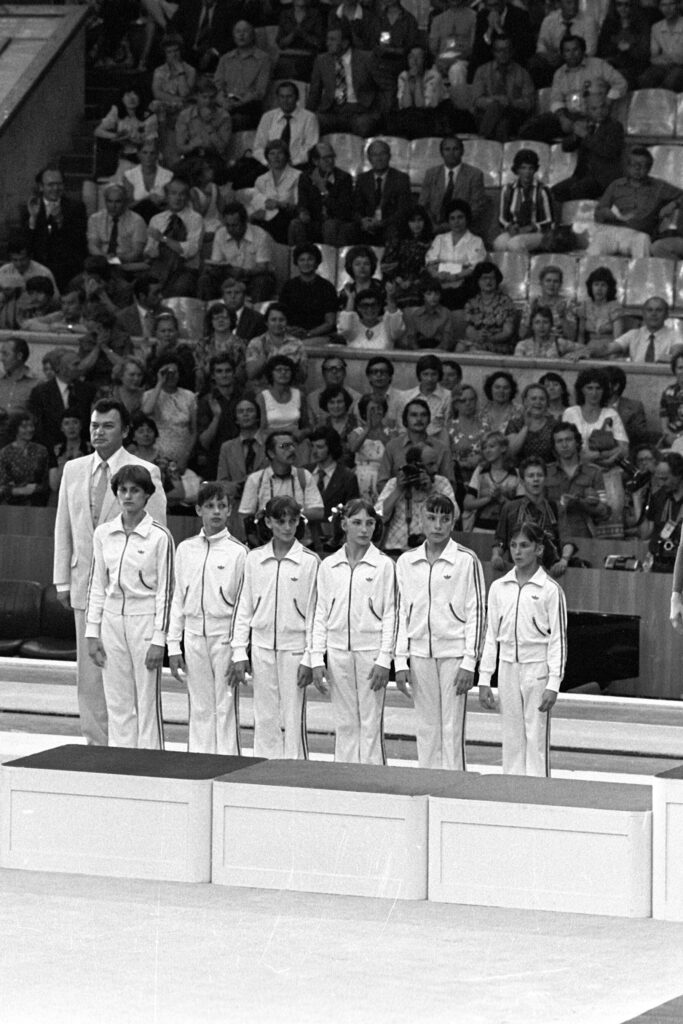

After more than two decades, Rodica Dunca, now 38 years old, found the courage to tell ProSport readers shocking details about life in the Deva training camp. In the testimony of the former athlete appear the names of her teammates from the national squad, the women who won the 1979 world team title in Fort Worth: Nadia Comăneci, Melitta Rühn, Dumitrița Turner, Emilia Eberle, as well as Teodora Ungureanu, Olympic silver medalist in 1976.

Nicknames Given by Károlyi

- Rodica Dunca — “manure”

- Emilia Eberle — “the monument of stupidity”

- Melitta Rühn — “the mule”

- Dumitrița Turner — “the embryo from a cow’s belly”

- Nadia Comăneci — she didn’t have a nickname, but Károlyi often addressed her like this:

“You act like some big star, but there’s nothing to you. You’re an idiot.”

“We fed the girls from Nadia’s generation steaks four or five times a week. During the rest of the week they were given grilled chicken or fish. In addition, they could eat salad and fruit to their heart’s content. We also had cups of cold milk in the gymnastics hall, from which they could drink during training.”

— excerpt from No Fear, by Béla Károlyi

Who Is Béla Károlyi?

Béla Károlyi (60 years old, pictured) and his wife Márta Károlyi took over Romania’s national gymnastics team in the 1970s. Shortly thereafter, results began to appear, with Nadia Comăneci winning the European all-around title in 1975 and the Olympic all-around title in 1976.

Until 1981, when Károlyi fled to the United States, team and individual medals accumulated for the Romanian women. Later, Béla and Márta became coaches of the United States national team, with which they won the world title in 1991 and the Olympic title in 1996.

At the Atlanta Olympic Games, Kerri Strug (pictured) was the last gymnast still in competition. She performed her first vault but fell, injuring herself. At the coach’s urging—and despite the pain—she completed the second vault as well, landing on one leg. The score she received allowed the American team to climb onto the top step of the podium.

Károlyi: “You’re Disgraceful!”

In 1983, the team that Béla Károlyi had abandoned two years earlier traveled to Canada to take part in the 1983 Summer Universiade Edmonton, hosted by the city of Edmonton.

“When we laid eyes on him there, we froze,” says Rodica Dunca.

“We didn’t know how to react. But he did. Do you know what he said to us? ‘You’re disgraceful!’ We didn’t respond at all, just moved on. But the Securitate officers who traveled with us at all times forbade us from having any dialogue with Károlyi.”

The Dollars from Nadia’s Letters

One of the few moments when Károlyi’s former pupils managed to relax in the Deva training camp came when the postman delivered the sack of letters addressed to Nadia Comăneci.

“We used to beg her to let us open them for her. We’d fight over them. The greatest joy was when we found a dollar or a German mark slipped in among the pages. Nadia let us take all of them,” Dunca recounted.

Note #1: Rodica’s family name is Kőszegi. Her name was reportedly changed so that it would sound Romanian. Here’s how her change of name was recorded:

Köszeghy Béla-György, residing in Baia Mare, [Redacted Address], Maramureș County, requests the change of his child’s family name—Köszeghy Rodica, residing at the same address, born on May 16, 1965, in Baia Mare, Maramureș County, daughter of Béla-György and Maria Köszeghy—from Köszeghy to Dunca-Köszeghy, so that she shall be known as Dunca-Köszeghy Rodica.

Buletinul Oficial al Republicii Socialiste România, September 18, 1976

This name change coincided with Rodica’s tryouts for Romania’s expanded national team in September 1976. She was selected alongside Gabi Gheorghiu, Emilia (Gertrude) Eberle, and seven other gymnasts (Sportul, September 14, 1976).

The Hungarian-language press occasionally referred to her as “Dunca Kőszeghy Rodica.” See, for example, the Sept. 30, 1980, edition of Hargita.

Note #2: Dumitrița Turner (Dana Beck) confirmed that the gymnasts were given an obscene number of pills.

Choreographer Geza Poszar said in an old interview that aggressive food restriction, abuse, and strenuous training were also intended to delay girls’ puberty, as it had negative effects on performance. Have you experienced the same feeling?

– I didn’t realize it then, but with the mind, over the years it’s probably some truth. For example, they used to make us take drugs with our fists. We’d flush some of them down the toilet, but when they got caught, they’d make us swallow them in front of them. There were pills we knew, like vitamins, but also others we had no idea about. But I didn’t feel anything special after taking them. Maybe there were also enough painkillers, because we had permanent bandages on our hands, on our feet, with all kinds of injuries. I remember that I took part in the 1981 World [Championships] in Moscow with a broken ankle when Bela was no longer there because he had run away. I put a cast on it, but it came off after three days and I competed in terrible pain. It was the worst competition of my career. And we came 4th on the team competition.

– Are you left with any physical sequelae?

– Nothing serious. But at one point during the activity, I couldn’t even go to the bathroom because of the pain. I had to warm up my ankles a bit first to be able to walk. And all the girls were the same.

More Interviews and Profiles

One reply on “2002: Rodica Dunca – “At Deva, It Was a Concentration Camp””

It is a very sad interview. Hopefully life is kinder to her now.

Georgia Cervin in her 2021 book “Degrees of Difficulty”, p.125, wrote ” A small number of gymnasts, from a variety of different countries, have tested positive for doping with furosemide, and each has been banned for at least one year for that transgression. Comment from Romanian officials and FIG insiders, however, suggests that doping in Romania was more systematic, at least until the year 2000, when Raducan was stripped of her gold medal in the all-around after the team doctor gave her, and allegedly the entire team, pseudoephedrine. This evidence shows that over the last four decades, at least, coaches, officials and even medical staff have conspired to break the rules in order to win medals, thereby jeopardizing gymnasts’ careers and health”.