In April 2010, the International Olympic Committee stripped China’s women’s gymnastics team of its bronze medal from the 2000 Sydney Olympics. The decision followed an eight-month investigation by the International Gymnastics Federation (FIG), which concluded that team member Dong Fangxiao had been 14 years old at the Games—two years below the minimum age of 16.

The English-language coverage of the scandal—the discovery of conflicting documents, the investigation, the ruling, and the redistribution of medals—has been extensively documented. Less familiar to English-speaking audiences is how the case unfolded inside China: how state media framed the ruling, how sports officials explained it to the public, and how Chinese journalists and commentators responded.

What emerged was not a single narrative, but a fractured one. Alongside brief, formulaic official statements ran a parallel discussion in China’s press that questioned responsibility, credibility, and the structure of a state-run sports system that governed athletes’ lives long before—and long after—the medal was won.

The Investigation

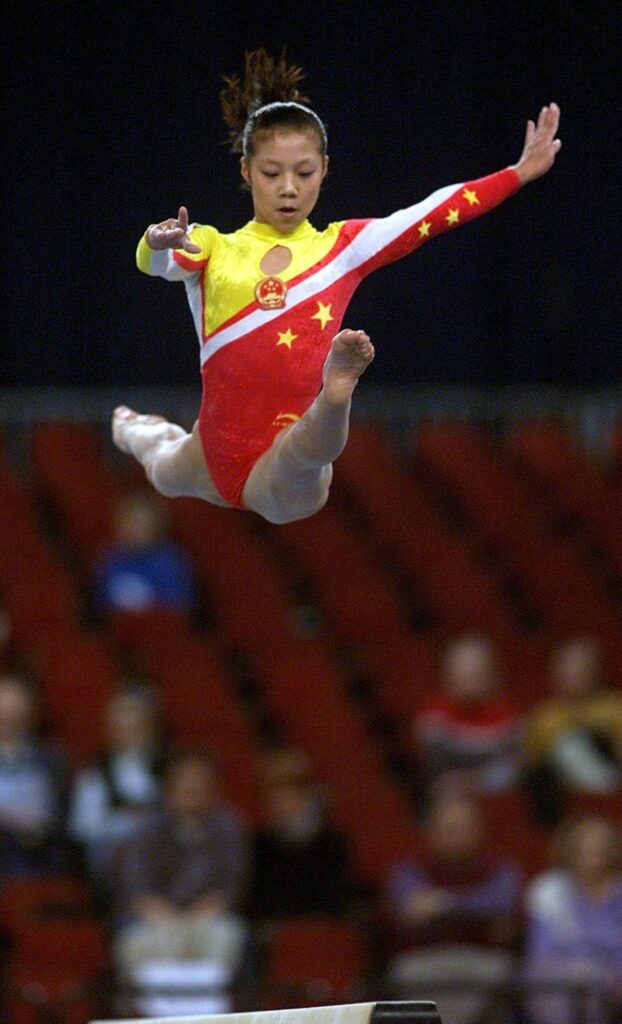

The discrepancy first surfaced at the 2008 Beijing Olympics in the midst of questions about the ages of He Kexin, Jiang Yuyuan, and Yang Yilin. While serving as a technical official at the gymnastics venue, Dong’s accreditation listed her birthdate as January 23, 1986. But in the International Gymnastics Federation’s records from her days as a competitor, she was born January 20, 1983—a difference of almost exactly three years.

André Gueisbuhler, the FIG’s secretary general, told reporters in October 2008 that Dong’s Beijing credential documents showed the 1986 birthdate. Her blog, he noted, indicated she was born in the Year of the Ox in the Chinese zodiac, which ran from February 1985 to February 1986. When contacted by the Associated Press, Dong said, “If the FIG wants to investigate this matter, I will provide every form of documentation.”

The investigation formally began in June 2009. The FIG announced it had established a Disciplinary Commission to examine whether Dong and her teammate Yang Yun had violated age requirements at the Sydney Olympics. Yang had stated in a 2007 interview on China Central Television that she was 14 at the Sydney Games, though she later told reporters she had “misspoken.”

The creation of a formal disciplinary commission marked a sharp departure from the FIG’s past practices. In earlier age falsification cases, the federation had acted informally or not at all. When Kim Gwang Suk’s age discrepancies emerged in 1993, the FIG questioned North Korean officials, was not convinced by the DPRK federation’s responses, and quickly took action, barring the federation from the following World Championships. When Romania’s age scandal surfaced in 2002, the FIG allowed the Romanian Olympic Committee to investigate itself, and despite public admissions that falsification had occurred, it imposed no sanctions. Never had the federation convened a dedicated commission to investigate and adjudicate an age case over the course of several months—let alone one that would reevaluate a gymnast’s age years after her competitive career ended.

In February 2010, the FIG announced its findings. The Commission determined that Dong had been 14 at the Sydney Olympics and annulled all her results from that competition, from the 1999 World Championships in Tianjin, and from the 1999-2000 World Cup events. At a December 2009 hearing, Dong had said she was born in 1983, but the passport she produced showed 1986. Yang Yun received a warning but kept her individual bronze on uneven bars from Sydney; the Commission found her televised statement insufficient to constitute “clear and objective evidence.”

Two months later, the IOC followed suit, revoking China’s team bronze medal and awarding it to the United States. Five other Chinese gymnasts—Yang Yun, Liu Xuan, Ling Jie, Huang Mandan, and Kui Yuanyuan—lost their team medals along with Dong.

The nature of the sanction was unprecedented at the time. In the case of Kim Gwang Suk (1993) and Hong Su Jeong (later in 2010), the FIG had imposed forward-looking penalties, barring the federation from future World Championships, but the gymnasts kept their medals. China faced no such ban. Instead, the federation reached backward, voiding results from competitions held a decade earlier. This retroactive approach would later become precedent: in 2014, the FIG annulled Cha Yeong Hwa’s results after a birthdate inconsistency surfaced during her license renewal, but the federation did not ban the North Korean federation from future competitions. (Hong Un Jong went on to win the vault title at that year’s World Championships.)

Once the sanctions were finalized and the medals reassigned, the case moved out of the investigative phase and into one of explanation. In China, the early public response was tightly controlled, even as dissenting voices began to emerge.

China’s Reaction

When the FIG released its decision at the end of February 2010, Gymnastics Center director Luo Chaoyi contested the verdict. Speaking to reporters, he insisted that “regarding Dong Fangxiao’s age at the 1999 World Championships and the 2000 Sydney Olympics, the Chinese team is confident that there was no age falsification involved.” Any discrepancy, Luo argued, arose only after Dong’s retirement: her birth year had been reduced by three years later and “should be considered the action of the athlete herself and her family,” rather than evidence of wrongdoing during her competitive career.

Journalists were quick to question those remarks. Cao Jingxing, writing for China National Radio, took issue with the Chinese Gymnastics Association’s expression of “regret” over the FIG’s decision, asking, “Regret over what? Regret over the International Gymnastics Federation’s decision, or regret over ourselves?”

“If the Chinese side believes the International Gymnastics Federation’s decision is incorrect,” Cao argued, “then it should present concrete evidence to mount a defense and lodge a protest. If we have no evidence and are unable to defend ourselves, then expressing regret is of no use. Instead, we should seriously examine exactly where our own problems lie.”

In the Beijing Morning Post, journalist Liu Yishi pointed to the source of the problem. Recalling a conversation with a world-champion gymnast not yet twenty years old but already contemplating retirement as her body changed, Liu argued that age scandals could not be understood as the result of an individual’s deception. “How could a thirteen- or fourteen-year-old child,” he asked, “really understand what steps were necessary to ensure that her age was correctly registered with the International Gymnastics Federation?” Athletes did not manage their own documents. As Liu put it, “The most common thing journalists hear athletes say is: ‘After I joined the national team, everything was done according to instructions from the top.’”

The leadership’s inversion of responsibility—placing blame on those least capable of exercising agency—was the core target of a far more scathing commentary by Liu Hongbo in the Southern Metropolis Daily. “The falsifying of ages in Chinese sports is not a secret,” he wrote, “but a more or less openly acknowledged fact.” Athletes carry multiple birthdates across student records, athlete registrations, ID cards, and work permits. “Even the specific days and months of the birthdays of Chinese athletes are impossible to get clear,” he wrote—“there are so many versions and changes.” (Even the day of Dong’s birth differed between her competitive life—January 20, 1983—and post-competitive life—January 23, 1986. See also Ma Yanhong’s age.)

But this was not a problem created by provincial bureaus, families, or individual athletes. “Sport in China is an act of state,” Liu argued. When the nation exercises full authority over sport, it bears full responsibility for the consequences. Individual fraud might have personal motives, but when it recurs across programs and decades, it can no longer be dismissed as an accident or a deviation. “When athletic fraud becomes a common occurrence,” Liu argued, “it is difficult to deny that this is a form of institutionalized behavior.”

“If we cannot even convince others of the ages of our athletes,” Liu Hongbo warned, “how can we earn the trust of the world?” The issue, he argued, was not only about gymnastics—or even sport—but about credibility itself. When even an athlete’s birthdate could not be trusted, skepticism would not stop at the gymnasium. It would extend outward—to academic degrees, work histories, company reports, and government statistics—undermining confidence in information provided by China more broadly.

By late April 2010, the initially defensive posture of Chinese officials gave way to a markedly different tone. After the IOC endorsed the FIG’s findings and stripped the Chinese women’s team of its Olympic bronze medal from Sydney, the Chinese Olympic Committee issued a statement saying it “respected” the decision and “attached great importance” to it. Luo Chaoyi said the team would comply with the ruling and return the medal within a week. Team leader Ye Zhennan outlined new safeguards—“strictly checking four documents,” including household registration booklets, ID cards, athlete registration certificates, and passports—and concluded on a note of contrition: “For this incident, we are deeply saddened. We must take it as a warning … and resolutely prevent similar incidents from happening again.”

The Family Explanation

But how had it happened? After the IOC’s decision in April 2010, another story emerged in Chinese media—one that explained how Dong’s family supposedly falsified her age. In this telling, age manipulation was not denied but normalized. It was framed as part of China’s lived social reality and, in Dong’s case, even as a practical necessity.

Writing for the Yangcheng Evening News, the journalist Lin Benjian (林本剑) recounted Dong’s story. After the 2000 Olympics, she went on to win five gold medals at the East Asian Games and two more at the University Games. Her last competition was China’s National Games in late 2001.

Eight months later, Dong underwent surgery for avascular necrosis of the femoral head; her bone tissue was dying from insufficient blood flow. She would spend the next two years largely bedridden.

After recovering from injury, Dong Fangxiao studied French at Beijing International Studies University and qualified as an international-level gymnastics judge, with plans—supported by Hebei team leadership—to return to the provincial program after graduation. Those plans collapsed in 2008, when foreign media revived questions about her Olympic eligibility and Huang Jian, the Hebei gymnastics director who had backed her return, was killed in a traffic accident, leaving her without institutional support. In the summer that followed, Dong and her boyfriend left for New Zealand to study, where she supported herself in part by coaching children’s gymnastics

“It’s been ten years,” the article quoted Dong’s mother saying. “Why has my Xiaoxiao always been so unlucky?”

Yes, she reportedly confirmed, Dong’s age had been changed, but only in 2002, during her surgery and recovery period. “At the time, some people suggested that since Xiaoxiao would need to stay in bed for two or three years after surgery, they worried that once she recovered, she’d be considered too old to find work. So they suggested changing her age—essentially ‘making up’ for those two or three years spent bedridden.”

According to the newspaper, Dong’s mother insisted her daughter had been born in 1983, making her legal to compete in Sydney, and that the 1986 birthdate was the falsification—a later adjustment that somehow appeared in official Olympic accreditation systems six years after it was allegedly created.

When asked why international authorities should believe this version, she said, “This is China’s reality. How do you explain that to foreigners? They don’t understand.”

She offered an example. Her own official ID card showed the wrong birthdate—the same year, month, and day as her husband’s, despite being four years younger. When she went to the police to correct it, “they said, ‘It’s just a date—why bother? Isn’t being older better?’ They even scolded me.”

The term she used was “中国国情”—China’s national conditions. Document irregularities are common, she suggested, and expecting Western standards of documentary precision misunderstands how bureaucracy works.

The explanation created its own questions. If Dong’s age was changed in 2002, how did the 1986 birthdate surface in her official credentials at the 2008 Beijing Olympics—six years later and long after her competitive career had ended? Olympic accreditation requires documentation submitted through national Olympic committees and sports federations. The path from a 2002 document change by an individual and her family to a 2008 official Olympic credential issued through state sports administration channels was not explained.

The Kiwi Perspective

But Dong Fangxiao’s mother was not the only family member to speak on her behalf. By the time the case moved toward resolution, Dong was no longer living in China. She had left with her boyfriend—soon to become her husband—and a different version of events would surface from New Zealand.

In October 2009, while the FIG investigation was still underway, Li Te, Dong’s husband, told the Waikato Times that his wife had been born in 1986 and had turned twenty-three that January, which would have made her fourteen at the Sydney Olympics. He also insisted she had done nothing wrong and that the matter had already been resolved. The couple had moved to New Zealand to study and hoped to settle permanently. Dong was coaching young gymnasts and imagined one day returning to the Olympics—not as a competitor, but perhaps as a coach.

In March 2010, the Associated Press reported that the Waikato District Council in New Zealand had published Dong’s curriculum vitae online to comply with public transparency requirements. The Huntly Gymnastics Club had applied for local government funding to hire Dong as a coach, and her CV was part of their submission. It listed her birthdate as January 23, 1986—the same date that appeared on her 2008 Beijing Olympics accreditation.

In September 2010, after the FIG’s and IOC’s decisions, the Waikato Times printed another story about Dong. Coaching at two clubs in New Zealand, she offered one of her few public comments on the controversy. “I think nothing’s happened to me,” she told the Waikato Times. “The results and all the medals all passed by when I was retired from gymnastics.”

At the time, the couple was focused on finding a way to stay in New Zealand, where the couple felt supported. Dong’s husband remarked, “We have heard from many people, friends, and Kiwi local people, especially the parents of the kids, saying ‘Fangxiao, we love you, we want you to stay here,’ so we very appreciate that.”

In 2019, Gymnastics New Zealand recognized Dong for eight years of service as an international judge. The couple had realized their goal of staying in their adopted home, and despite everything that happened to her, Dong continued working in the sport that had defined her early life.

Notes

1. By 1998, Dong’s 1983 birth year was already in place in the press. In an article about the national championships, the People’s Daily highlighted a new generation of female gymnasts, noting that Dong Fangxiao was among a group of 14- and 15-year-olds. With a 1983 birth year, she would have been 15 in 1998.

At the previous World Championships, Zhang Jian, director of the national gymnastics management center, had expressed concern over the lack of depth in the women’s program. This time, however, a number of 14- and 15-year-old gymnasts delivered impressive performances: Huang Mandan, Peng Sha, and Chen Miaojie of Guangdong; Xu Jing and Bai Chunyue of Beijing; Dong Fangxiao of Hebei; and Ling Jie and Chen Mi of Hunan.

The most outstanding among them was 15-year-old Huang Mandan of Guangdong. Competing in her first national championship, she claimed third place in the women’s all-around. Facing a field filled with established stars, she demonstrated remarkable technical level and uncommon courage.

The People’s Daily, September 22, 1998; I’ve placed the names of the 2000 Olympic team in bold.

上届世锦赛时,国家体操管理中心主任张健还在为女队的后备力量的不足而担忧。而这次,广东的黄曼丹、彭莎、陈淼洁,北京的许婧、白春月,河北的董方宵,湖南的凌洁、陈密等一批年龄在14、15岁的小将表现喜人。其中最为突出的当属广东15岁小将黄曼丹,这位第一次参加全国大赛就夺得女子全能第三名的小姑娘面对众多名将,表现出高超的水平和不凡的勇气。

2. Had the FIG’s current Code of Discipline been in force in 2000, Dong Fangxiao would not have been investigated. By 2008, any potential case would have been time-barred and no longer subject to further scrutiny.

3. Dong’s case also invites a broader question: was Dong truly the first former gymnast to carry a different birthdate into her post-competitive career? Gina Gogean, for example, became an international judge in 2001, just four years after her final World Championships. Which birth year did she use—1977 or 1978—when she became a judge?

A Tangential Note

After the 2016 Olympics, the People’s Daily, China’s main newspaper, questioned the country’s approach to choosing young gymnasts:

Now is the time to say goodbye to the practice of selecting very young, underdeveloped, and diminutive athletes solely to raise difficulty levels. Experience has shown that China is fully capable of catching up: Ma Yanhong, China’s first women’s world gymnastics champion, was already a grown woman when she won her title, and Liu Xuan captured Olympic gold at the age of 20. Chinese women possess exceptional technique, ideal physiques, and mature feminine grace—qualities fully capable of surpassing their European and American counterparts.

Zhang Baoshu, People’s Daily, August 17, 2016

现 在 到 了 与 选 拔 低 龄 、 未 发 育、身材娇小运动员,以提高动作 难度的做法说再见的时候了。经验 证明,我们完全有能力迎头赶上: 中国女子体操第一个世界冠军马燕 红夺冠时就是“大姑娘”,刘璇也是 在 20 岁时获得奥运金牌。中国女孩 高超的技巧,完美的身材,成熟女 性的魅力,完全有超过欧美女孩的 实力。

Note: With a competitive birthdate of August 12, 1979, or March 12, 1979, depending on the source, Liu Xuan would have been 21 in Sydney.

The idea of extending gymnasts’ competitive careers resurfaced in a 2022 article published in China Sport Science. The authors—Peng Zhaofang, Wu Yunlu, Guo Wei, and Yuan Ling—argued that existing training and development strategies exhibited several structural shortcomings:

Women’s artistic gymnastics is characterized by high technical difficulty and complex routine composition. The period during which athletes can maintain competitive form is relatively short; peak performance tends to appear early, and it is difficult to sustain a high level of competitive ability in later stages.

[…]

This, to a certain extent, constrains the sustained competitiveness of China’s women’s gymnastics program.

They proposed extending athletes’ “sporting lifespan” (延长运动寿命) through scientific training, injury prevention, and improved load management so that the women’s program could avoid a “’flash-in-the-pan’ development model and enhance athletes’ capacity to compete across multiple cycles while continuously producing high-level results.”

If China’s women’s gymnastics program heeds this advice, perhaps we will see more gymnasts like Deng Yalan, who competed at the 2025 World Championships after a long hiatus from international competition.

The Interview with Dong’s Mother

Dong Fangxiao’s Mother Reveals the Truth Behind the “Age-Alteration” Controversy, Insisting Her Daughter Was Born in 1983

Date: May 1, 2010

Reporter: Lin Benjian

Source: Yangcheng Evening News

Exclusive Interview

- Around 2000, she was surrounded by flowers, applause, and honor; a year later, however, a diagnosis of avascular necrosis of the femoral head left her uncertain about the future.

- In 2008, she hoped to return to work with the Hebei gymnastics team, but the plan fell through after a leadership figure died unexpectedly.

- In 2010, she hoped to work as an amateur coach in New Zealand, but that dream has now been shattered by a single decision from the International Olympic Committee…

After repeated setbacks, she leaves for New Zealand with her boyfriend

Time flies. In the blink of an eye, it has been nearly eight years since I first came to know Dong Fangxiao.

On September 15, 2002, I went to Dong Fangxiao’s home in Tangshan to interview her. At the time, she had not long since undergone surgery for avascular necrosis of the femoral head and could walk only with the help of crutches. Not yet 20 years old, at what should have been the prime of her youth, she lay in bed day after day, relying on a few photo albums to recall her brief yet glorious gymnastics career.

The Dong Fangxiao before me was no longer the spirited “Little Oriental Deer” from the competition floor. Long-term bed rest after surgery had made her look completely different from her athletic self. The captivating confidence once seen in her eyes was gone, replaced by fear of injury and confusion about the future. Dong’s mother spent her days in tears. She said that if it were possible, she would trade all of Xiao Xiao’s honors for her health. To her, nothing mattered more than her daughter’s well-being. This was the natural outpouring of a great mother’s love, without the slightest affectation.

Before leaving the next day, I deliberately bought a foreign-made doll about the same height as Xiao Xiao. She was so happy she couldn’t stop smiling. With that doll, Xiao Xiao was no longer alone. Many years later, when we met again, she said to me, “Thank you for that doll.”

Before the 2001 National Games, Dong Fangxiao’s life was surrounded by flowers, applause, and honor. She won team bronze medals at both the World Championships and the Olympic Games; team and floor exercise gold medals at the World University Games; and two gold medals—women’s team and floor exercise—at the National Games. Dong Fangxiao had nearly achieved everything that a Chinese women’s gymnast of that era could.

However, after the National Games, she was diagnosed with avascular necrosis of the femoral head, and her life began moving toward the opposite extreme—long-term struggle with illness.

On August 8, 2002, she underwent surgery at the Third Hospital of Hebei Province. The medical costs were covered by the Gymnastics Administrative Center of the General Administration of Sport and the Hebei Provincial Sports Training Center. At the time, Dong Fangxiao’s family circumstances were very difficult. Before the National Games, her monthly salary was 1,060 yuan; after the Games, it rose to 1,100 yuan. In 2001, Dong’s mother retired early to care for her daughter. Dong’s father worked away from home. Combined, the family’s monthly income was still under 3,000 yuan. The three of them lived crowded together in a small apartment of less than 40 square meters.

Before the National Games, Hebei Province awarded apartments to National Games champions, but by the time of the Ninth National Games, this policy had been canceled. Dong Fangxiao received only a 100,000-yuan bonus in 2003—still not enough to buy an apartment in Tangshan.

After recovering, Dong Fangxiao went to Beijing International Studies University to study French and successfully qualified as an international-level gymnastics judge, continuing her gymnastics dream. Whenever we met at competitions, Dong Fangxiao was always smiling, working hard to emerge from the shadow of her injuries. At the time, leaders of the Hebei gymnastics team hoped that she would return to serve the Hebei team after graduation.

Just as she was preparing to welcome a new life with a smile, misfortune struck again. After the 2008 Beijing Olympics, foreign media reported that her age at the Sydney Olympics did not meet eligibility requirements. At the same time, Huang Jian—the former director of the Hebei Provincial Sports Training Center’s gymnastics program, who had always admired her—was killed in a traffic accident during the Beijing Olympics. As a result, Dong Fangxiao’s wish to return to work with the Hebei gymnastics team fell through. She could only work as a temporary employee, earning very little income.

“Originally, they had agreed to let Dong Fangxiao return to the Hebei gymnastics team, but once Director Huang died, the matter just disappeared. Even people in the department said they didn’t know about it, and no one spoke up for us. Sigh—when you’re capable, people can make use of you; now you have no value at all, who would care about you? Our family has no money and no background—it doesn’t work. Now that this has happened, we can’t even live an ordinary, peaceful life anymore.”

Last summer, Dong Fangxiao and her boyfriend went to New Zealand to study. Her language skills have now passed the basic threshold, and she plans to pursue further education. Before the International Olympic Committee reclaimed her Olympic bronze medal, Dong Fangxiao used her spare time to teach children gymnastics at a local club in New Zealand.

“She originally just wanted to see whether she had the ability in this area. Now that this has happened and everyone knows about it, she’s too embarrassed to go back,” Dong’s mother said sadly. “It’s been ten years—why has my Xiao Xiao been so unlucky all this time?”

Dong Fangxiao’s mother responds: My daughter was born in 1983

Since the age issue was exposed after the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Dong Fangxiao and her family have been caught in a vortex of public opinion, and the Dong family has consistently chosen to remain silent. Exactly how old was Dong Fangxiao when she competed at the 2000 Sydney Olympics? Yesterday, in an exclusive interview with a Yangcheng Evening News reporter, Dong Fangxiao’s mother stated that Dong Fangxiao was indeed born in 1983, and that her age was altered in 2002, during the period when she underwent surgery for avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

In recent days, everyone in the Dong family has been in low spirits. “You tell me—how can this child be so unlucky?” Dong’s mother sighed over the phone. “There’s really no way to explain this clearly anymore. Xiao Xiao was indeed born on January 20, 1983. During her surgery in 2002, some people suggested that after the operation she would need to stay in bed for two or three years. They worried that once she recovered, she would be considered too old and would have difficulty finding work, so they suggested changing her age—just to make up for those two or three years spent bedridden.”

After the 2001 National Games, Dong Fangxiao was diagnosed with late-stage avascular necrosis of the left femoral head and underwent surgery in August 2002. Dong’s mother revealed that during the surgery period, Xiao Xiao always held on to the hope of returning to gymnastics afterward, “because she truly loved gymnastics too much.”

Regarding the International Gymnastics Federation’s decision to cancel Dong Fangxiao’s medals from the 1999 World Championships and the 2000 World Cup, as well as the International Olympic Committee’s decision to revoke the bronze medal she won as part of the women’s team at the 2000 Sydney Olympics, Dong’s mother was deeply saddened. “Many things are not something we can decide. We tried to explain China’s national circumstances to the FIG, but we couldn’t make it clear. You say Xiao Xiao’s age was a problem in competitions ten years ago—then why didn’t you produce evidence at the time? Xiao Xiao had her ID card and everything, and there was even bone-age testing back then. If she hadn’t passed, she wouldn’t have been allowed to compete. Now you say her age was insufficient and annul her results—there’s no justification. My daughter being ill is a fact. If changes happened because of that, what’s so unacceptable about it? Saying Xiao Xiao was born on January 23, 1986—that’s what’s truly wrong. But even if it’s wrong, what can we do? Even my husband’s and my own ID cards aren’t correct.”

Dong’s mother firmly insisted that her daughter was born on January 20, 1983, and expressed helplessness in the face of the IOC’s decision.

[…]

董芳霄妈妈曝光改龄门真相 坚称女儿1983年出生 独家专访 ●2000年前后,她被鲜花掌声和荣誉包围,可一年后患上“股骨头坏死”令其对未来充满茫然;

●2008年,想回河北体操队工作却因领导意外去世而胎死腹中;

●2010年,想在新西兰当业余教练,而今被国际奥委会的一纸处罚击碎梦想……

连遇挫折 与男友赴新西兰

岁月如梭,一转眼,认识董芳霄已经快8年了。

2002年9月15日,我曾前往董芳霄在唐山的家中采访。当时的她刚经历股骨头坏死手术不久,行走只能靠拐杖。不到20岁,正值花样年华之际,却终日卧病在床,依靠几本相册回忆那短暂而又辉煌的体操生涯。眼前的董芳霄,已经不再是那个体操场上充满灵气的“东方小神鹿”。由于手术后长期卧床,她与体操场上的形象判若两人,眼神里已经没有了赛场上那种迷人的自信,取而代之的是对伤病的恐惧和对未来的茫然。董妈妈终日以泪洗面,她说,如果可以,愿意用霄霄所有的荣誉换回一个健康的霄霄,对她来说,没有什么比女儿的健康更重要。那是伟大母爱的自然流露,没有丝毫的做作。 第二天临走前,我特意买了一个跟霄霄个儿差不多高的洋娃娃。霄霄高兴得合不上嘴,有了那个洋娃娃,霄霄便不再孤独。多年以后再见面,她跟我说,谢谢你送的那个洋娃娃。 2001年九运会前,董芳霄的人生被鲜花、掌声和荣誉包围。世锦赛、奥运会都拿到团体第三,世界大学生运动会团体和自由操双冠,九运会女团和自由操两枚金牌。董芳霄几乎做到了当时中国体操女运动员所能做的一切。然而,自九运会后被查出患有股骨头坏死,她的人生开始走向另一极———长期与病魔做斗争。 2002年8月8日,她在河北三院动了手术,医疗费由国家体育总局体操中心和河北省体工队体操中心支付。当时,董芳霄的家境很困难。九运会前,她的月工资是1060元,九运会后涨到1100元。董妈妈为了照顾女儿,在2001年提前退休,董爸爸在外地做事,月收入与霄霄的工资相加还不到3000元,一家三口挤在不到40平方米的小房子里。九运会前,河北省的全运会冠军都有奖励房子,可九运会时河北省取消了这一奖项,董芳霄只在2003年得到10万元奖金,还不够在唐山买一套房子。 伤愈后,董芳霄到北二外学习法语,顺利考取了体操国际级裁判,继续着她的体操梦。每次在赛场碰面,董芳霄总是笑容满面,她正努力走出伤病的阴霾。当时,河北体操队的领导希望董芳霄毕业后回河北队效力。然而,正当她准备以微笑迎接新生活时,厄运再次缠上她。2008年北京奥运会后,她被国外媒体报道在悉尼奥运会参赛时年龄不符合要求。而一直很欣赏她的原河北省体工大队体操中心主任黄健在北京奥运会期间不幸出车祸身亡,这使得董芳霄回河北体操队工作的愿望落空,只能当一名临时工,收入甚微。“原本答应让董芳霄回河北体操队了,可黄健主任一死就没下文了,连科室的人都说不知道这事,没有一个人替我们说话。嗨,你有能力时还可以利用,现在一点价值都没有了,谁理你啊?咱们家没钱,也没有背景,不好使。现在出了这事,连平平淡淡都没法过了”。 去年夏天,董芳霄和男友去了新西兰念书,现在语言已经过关,准备进一步深造。在国际奥委会收回她的奥运会铜牌之前,董芳霄在新西兰利用课余时间在当地一家俱乐部教小孩练体操。 “本来她想看看自己有没有这方面的能力,现在出了这事,别人都知道了,她也不好意思再去了。”董妈妈悲伤地说:“都10年了,我家霄霄怎么一直这么倒霉啊!” 董芳霄妈妈回应: 我女儿就是83年出生的 从2008年北京奥运会后被爆出年龄有问题至今,董芳霄及家人便处于舆论漩涡中,董家一直选择沉默。董芳霄在2000年参加悉尼奥运会时究竟有多大?昨天,董芳霄的妈妈在接受羊城晚报记者独家采访时表示,董芳霄确实是1983年出生的,年龄是在2002年董芳霄动股骨头坏死手术期间改的。 这几天,董家上下个个心情郁闷。“你说这孩子咋这么倒霉呢,”董妈妈在电话里叹道,“这事真没法说清楚了。霄霄确实是1983年1月20日出生的,2002年动手术期间,当时一些人建议,说霄霄手术后要卧床两三年。好了以后怕年龄大了,工作不好找,所以就建议把年龄改了,正好把卧床养病这两三年时间补回来。” 董芳霄在2001年参加九运会后不久被查出左侧股骨头坏死,并且已是晚期,在2002年8月动了手术。董妈妈透露,手术期间,霄霄一直抱有术后再练体操的念头,“因为她实在太爱体操了”。 对于国际体操联合会取消董芳霄1999年世锦赛和2000年世界杯的奖牌,以及国际奥委会取消董芳霄在2000年悉尼奥运会获得的女团铜牌的决定,董妈妈非常难过,“很多事情不是我们可以决定的,我们拿中国的国情跟国际体联去说,也说不明白。你说霄霄10年前参加的比赛年龄有问题,当时为什么不拿出证据?霄霄身份证什么的都有,而且当时还有骨龄测试,如果测试不合格,是不允许比赛的。现在说霄霄年龄不够,取消成绩什么的,没道理啊!我女儿有病这是事实,现在发生了变故,有啥不可以呢?说霄霄是1986年1月23日出生的,那才不对呢。可不对又能怎么样?我跟我家老头的身份证还不对呢,我家老头是1948年出生的,我比他小4岁,可我的身份证出生日期却是跟他同年同月同日。我找了几次派出所,要改回来,可人家却说,不就是一个日期嘛,你自己知道什么时候出生就行了,年纪大点有什么不好?还训了我一顿。这就是中国国情,可你跟老外怎么解释?他们不明白的。” 董妈妈坚称女儿是1983年1月20日出生的,对于国际奥委会的决定,董妈妈显得很无助。

The 2021 Code of Discipline

The 2025 Code of Discipline

References

Primary Sources

“Chinese Gymnasts Age Scandal at Sydney (AUS) in OG 2000.” Asian Gymnastics Union, February 27, 2010. https://agu-gymnastics.com/chinese-gymnasts-age-scandal-at-sydney-aus-in-og-2000/

“IOC EB Takes Decisions on Chinese Gymnast Dong Fangxiao.” International Olympic Committee, April 29, 2010. https://olympics.com/ioc/news/ioc-eb-takes-decisions-on-chinese-gymnast-dong-fangxiao

“IOC Strips China of 2000 Olympic Medal.” USA Gymnastics press release, April 28, 2010. https://usagym.org/ioc-strips-china-of-2000-olympic-medal/

English-Language News Coverage

Macur, Juliet. “Medal of Underage Chinese Gymnast Revoked.” The New York Times, February 26, 2010.

Macur, Juliet. “China Stripped of Gymnastics Medal.” The New York Times, April 28, 2010.

“China’s 2008 Gold Medalists Were Old Enough.” Associated Press, October 1, 2008.

Leicester, John. “China leaves underage gymnast in the cold.” The Associated Press, March 15, 2010.

New Zealand News Coverage

Goile, Aaron. “Olympics age-dispute gymnast living in Waikato.” Waikato Times, October 21, 2009.

Goile, Aaron. “Club will stand by tainted gymnast.” Waikato Times, April 29, 2010.

“Gymnastics: Chinese competitor loses medal.” Waikato Times, April 30, 2010.

Goile, Aaron. “Gymnast eyes coaching job.” Waikato Times, September 21, 2010.

Chinese-Language Sources

“Dong Fangxiao’s Mother Reveals the Truth Behind the Age-Alteration Scandal, Insists Her Daughter Was Born in 1983” [董芳霄妈妈曝光改龄门真相 坚称女儿1983年出生]. Yangcheng Evening News [羊城晚报], May 1, 2010.

“FIG Confirms Age Falsification by Dong Fangxiao, Annuls Her Sydney Olympic Results” [国际体联认定董芳霄年龄造假 取消其悉尼奥运成绩]. China News Service [中国新闻网], February 27, 2010.

“China Respects IOC Sanctions, Will Return Olympic Women’s Gymnastics Team Bronze Medal” [中国尊重国际奥委会处罚 将交回奥运体操女团铜牌]. China News Service [中国新闻网], April 29, 2010.

“IOC Formally Reclaims China’s Olympic Gymnastics Medal Over ‘Age-Gate’ Scandal” [国际奥委会因”年龄门”正式收回中国体操奥运奖牌]. China News Service [中国新闻网], April 29, 2010.

“China’s Women’s Gymnastics Team Sydney Olympic Bronze Medal Reclaimed” [中国体操悉尼奥运会女团铜牌被收回]. Digest Newspaper [文摘报], May 6, 2010.

“Training Center Says Gymnastics Age Falsification Was an Individual Act; Hopes FIG Will Withdraw Punishment” [中心称体操年龄造假是个人行为 望体联收回处罚]. China Youth Daily [中国青年报], March 1, 2010.

“We Should Reflect on the Dong Fangxiao Suspected Age-Falsification Case” [应反省董芳宵涉嫌年龄造假事件]. China National Radio [中国之声], commentary by Cao Jingxing, March 3, 2010.

“China’s Women’s Gymnastics Team Bronze Medal from the Sydney Olympics Revoked” [悉尼奥运会中国女子体操团体铜牌被收回]. Jiefangjun Bao (PLA Daily) [解放军报], April 30, 2010, p. 7.

“FIG Investigates Chinese Athletes’ Age Issues; Gymnastics Center Pledges Full Cooperation” [国际体联查中国选手年龄问题 体操中心积极配合]. CCTV.com, June 24, 2009.

“Chinese Media Tackle the National Sports System.” China Media Project, March 2, 2010.

More on Age