In the spring of 1990, just months after the Romanian Revolution, Ecaterina Szabó became one of the first Romanian gymnasts to publicly confirm what insiders had whispered about for years: the systematic age falsification of competitors by the Romanian Gymnastics Federation. Speaking to journalist Thomas Schreyer in Deva, Szabó revealed that she was born in 1968, not 1967 as her official gymnastics documents claimed—making her one year younger than the world had been told.

Despite the courage it took to come forward in a still-uncertain post-revolutionary Romania, Szabó’s confession was largely overlooked by the gymnastics community. Perhaps this was because the revelation didn’t retroactively change any of her competitive results. Even with her true birth year of 1968, Szabó would have been age-eligible for the 1983 World Championships in Budapest, where her international senior career began—she would have turned 15 that January, meeting the FIG’s minimum age requirement.

Ironically, this article would become a touchstone in gymnastics history not because of Szabó’s admission, but because of a single sentence about her close friend Daniela Silivaș. The article claimed Silivaș was “one year younger than previously stated,” and that news ricocheted around the globe. But the truth would prove even more dramatic: Silivaș was actually two years younger than her competitive age, making her age falsification far more consequential for the record books.

In this remarkable interview, Szabó discusses life after the Revolution, the mechanics of age falsification, and what it meant to be a gymnast in Ceaușescu’s Romania.

Boarding School in Deva Dissolved

Ecaterina Szabó: One Year Younger

For years, people in insider circles not only whispered about it but spoke openly as well. Yet no one really wanted to believe it. Not even FIG President Yuri Titov (USSR), who was repeatedly asked about it. The Romanian Gymnastics Federation had engaged in manipulation. The gymnasts were issued new documents so they could compete at World and European Championships even though they had not yet reached the required minimum age of 15.

Our contributor Thomas Schreyer traveled to Romania for the second time since the revolution. This time he brought back sensational revelations from authoritative sources. In Deva, the former Romanian training center, he spoke with Ecaterina Szabó, Daniela Silivaș, and their coach Leo Cosma—whose wife Maria had defected to the Federal Republic more than a year earlier.

The gymnasts affected are not to blame. But what will happen to the Romanian Gymnastics Federation? How will the FIG and the UEG respond? Will these manipulations have consequences? Questions that certainly require clarification.

The Editors

Deva

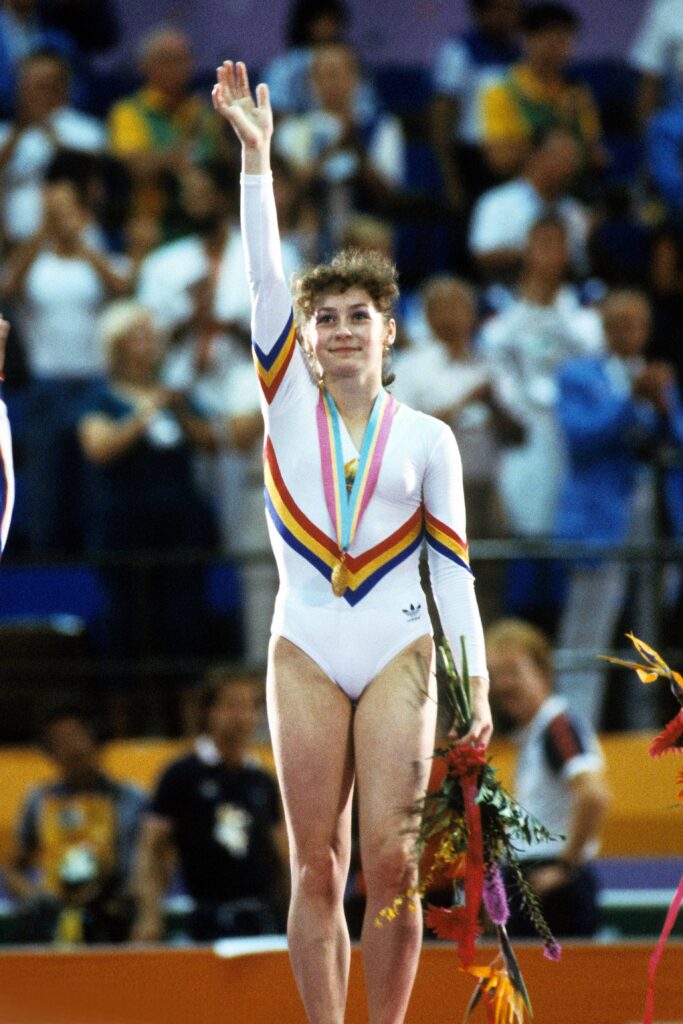

Until 1987, Ecaterina Szabó belonged to the absolute world elite. At the World Championships in Rotterdam, she won gold with the Romanian team. Today, Ecaterina Szabó—now an “F-student” (“fara frecventa,” meaning periodic university attendance)—is already a children’s coach and lives in Deva. She trains 19 girls in the second grade, aged 8 to 10.

Of the children who come from all over the country, “seven are already so good that something could come of them,” Szabó says. The young girls train twice a day: from 8 to 10 in the morning and from 2 to 5 in the afternoon.

The Revolution

Szabó spent the week before Christmas in the mountains with these girls. There, in Sinaia, they experienced the Revolution from afar. “We were really shaken,” the former Olympic champion recalls. “We didn’t know what was going to happen.”

The Revolution—“the first in the world to be broadcast live on television”—had “overwhelmed” her, she says. Still: “We weren’t doing politics, we were doing sport.” Now, everyone felt much “freer.” “We’re no longer being followed by the Securitate (secret police) and we can go anywhere.”

For Ecaterina Szabó, life had so far consisted of three phases: “The first, I was a gymnast; the second, when I stopped. The third phase was the Revolution and our liberation.”

Age Manipulation

Too many things in the “old days” had bothered her—things she simply had to put up with. “I don’t even want to list individual points; it was just too much,” says Kati Szabó, visibly irritated at being reminded of the brown-red terror of that time. But when confronted with direct questions, the student does not evade them: How did the age manipulation work?

“I was born on January 22, 1968, and not, as has always been claimed, in 1967.” For many gymnasts, the passports were simply falsified so the children could be sent to international competitions earlier. “It was no different for Lavinia Agache, or, to name someone from more recent times: Daniela Silivaș! For Daniela Silivaș too,” Szabó continues frankly, “the official documents were manipulated.” Daniela Silivaș, who is extremely close friends with Kati Szabó, is one year younger than previously stated and will not turn 19 until this May. “To this day we have no idea who was responsible for the falsification of the documents.”

Not Forced

At home, the gymnasts always celebrated their real birthdays. Since the 18th birthday—which also marks adulthood in Romania—is celebrated especially festively, neighbors and friends often learned about the manipulation.

But from the “prison that was Romania,” such information hardly reached the outside world; and when it did, it was ignored by representatives of the “free” Western media.

“I want to stress very clearly that, despite all the irregularities, we enjoyed doing our sport,” Szabó emphasizes. “None of us were forced.”

Of course, Szabó admits, it wasn’t just joy that drove young people in Romania into elite sport, but also fear of hunger and cold. A motivational factor that now disappears—and one that will, in the long term, change Romanian sport as well.

Thomas Schreyer

Olympisches Turnen Aktuell, April 1990

Internat in Deva aufgelöst

Ecaterina Szabó: Ein Jahr jünger

Über Jahre hinweg wurde in Insiderkreisen nicht nur darüber gemunkelt, sondern auch offen gesprochen. Keiner wollte es aber so recht wahrhaben. Selbst ITB-Präsident Juri Titow (UdSSR) nicht, der mehrfach darauf angesprochen wurde. Im Rumänischen Turnverband wurde manipuliert. Die Turnerinnen wurden mit neuen Dokumenten versehen, damit sie bei Welt- und Europameisterschaften starten konnten, obwohl sie das vorgeschriebene Alter von 15 Jahren noch nicht erreicht hatten. Unser Mitarbeiter Thomas Schreyer war nach der Revolution bereits zum zweitenmal in Rumänien. Nun brachte er die sensationellen Enthüllungen aus berufenem Munde mit. Er sprach in Deva, dem ehemaligen rumänischen Leistungszentrum, mit Ecaterina Szabó, Daniela Silivaș und ihrem Trainer Leo Cosma, dessen Frau Maria sich ja bereits vor über einem Jahr in die Bundesrepublik abgesetzt hat. Die betroffenen Turnerinnen sind schuldlos. Was passiert jedoch mit dem rumänischen Turnverband? Wie reagieren der ITB und die UEG? Haben diese Manipulationen Konsequenzen? Fragen, die sicher einer Klärung bedürfen.

Die Redaktion

Deva

Bis 1987 gehörte Ecaterina Szabó zur absoluten Weltspitze. Bei der WM in Rotterdam gewann sie noch Gold mit der rumänischen Mannschaft. Heute ist Ecaterina Szabó – als „F-Studentin“ (fara frecventa – periodischer Universitätsbesuch) – bereits Kindertrainerin und lebt in Deva. Dort trainiert sie 19 Mädchen der zweiten (Schul-)Klasse im Alter von 8 bis 10 Jahren. Von den Kindern, die aus dem ganzen Land kommen, sind, so Kati Szabó, „sieben schon so gut, aus denen könnte noch etwas werden“. Die kleinen Mädchen werden bereits zweimal am Tag trainiert, von 8 bis 10 Uhr am Vormittag und nachmittags von 14 bis 17 Uhr.

Die Revolution

Mit diesen Mädchen hielt sich Kati Szabó in der Woche vor Weihnachten in den Bergen auf. Dort, in Sinaia, erlebten sie aus der Ferne die Revolution mit. „Wir waren ganz schön bewegt“, erinnert sich die einstige Olympiasiegerin. „Wir wußten ja nicht, was wird“.

„Mitgenommen“ hätte sie die Revolution, die erste auf der Welt, die live im Fernsehen übertragen wurde. Dennoch: „Wir haben nicht Politik gemacht, sondern Sport“. Jetzt würden sich eben alle viel „freier“ fühlen. „Wir werden eben nicht mehr von der Securitate (Geheimpolizei) verfolgt und können überall hin“.

Für Ecaterina Szabó habe es bisher drei Phasen im Leben gegeben: „Die erste, da war ich Turnerin; die zweite, da habe ich aufgehört. Die dritte Phase war die Revolution und unsere Befreiung“.

Altersmanipulation

Zuviele Dinge hätten ihr „vorher“ nicht gefallen, hätte sie über sich ergehen lassen müssen. „Ich möchte da gar keine einzelnen Punkte aufzählen — es war einfach zu viel“, erzählt Kati Szabó, sichtlich etwas genervt, an die Zeit des braunroten Terrors erinnert zu werden. Doch Antworten auf direkte Fragen weicht die Studentin nicht aus: Wie war das mit den Altersmanipulationen?

„Ich bin am 22. Januar 1968 geboren und nicht, wie immer behauptet, schon 1967.“ Bei vielen Turnerinnen wurden die Reisepässe einfach falsch ausgestellt, um die Kinder früher zu internationalen Wettkämpfe schicken zu können. „Das war nicht anders auch bei Lavinia Agache, oder, um eine aus der heutigen Zeit zu nennen: Daniela Silivaș! Auch bei Daniela Silivaș“, fährt Kati Szabó ungeniert fort, „wurden die amtlichen Unterlagen manipuliert“. Daniela Silivaș, mit Kati Szabó engstens befreundet, ist ein Jahr jünger als bislang angegeben wurde und wird erst in diesem Mai 19 Jahre alt. „Wir haben bis heute keine Ahnung, wer für die Urkundenfälschungen verantwortlich war“.

Nicht gezwungen

Zuhause übrigens haben die Turnerinnen immer ihren richtigen Geburtstag gefeiert. Da vor allem der 18. Geburtstag, der auch in Rumänien die Volljährigkeit bedeutet, besonders groß zelebriert wird, haben oft auch Nachbarn und Freunde von der Manipulation erfahren. Doch aus dem „Gefängnis Rumänien“ drangen solche Informationen nicht nach außen; und wenn doch, so wurden sie von den Medienvertretern des „freien“ Westens ignoriert.

„Ich will aber ganz klar betonen, daß wir bei allen Unregelmäßigkeiten unseren Sport gerne betrieben haben“, unterstreicht Kati Szabó. „Niemand von uns wurde dazu gezwungen“.

Freilich, Kati Szabó muß zugeben, daß nicht nur die blanke Freude, sondern auch die Angst vor Hunger und Kälte junge Menschen in Rumänien zum Leistungssport getrieben haben. Eine Motivationskomponente, die nun entfällt und langfristig auch in Rumänien den Sport verändern wird.

Thomas Schreyer

More on Age