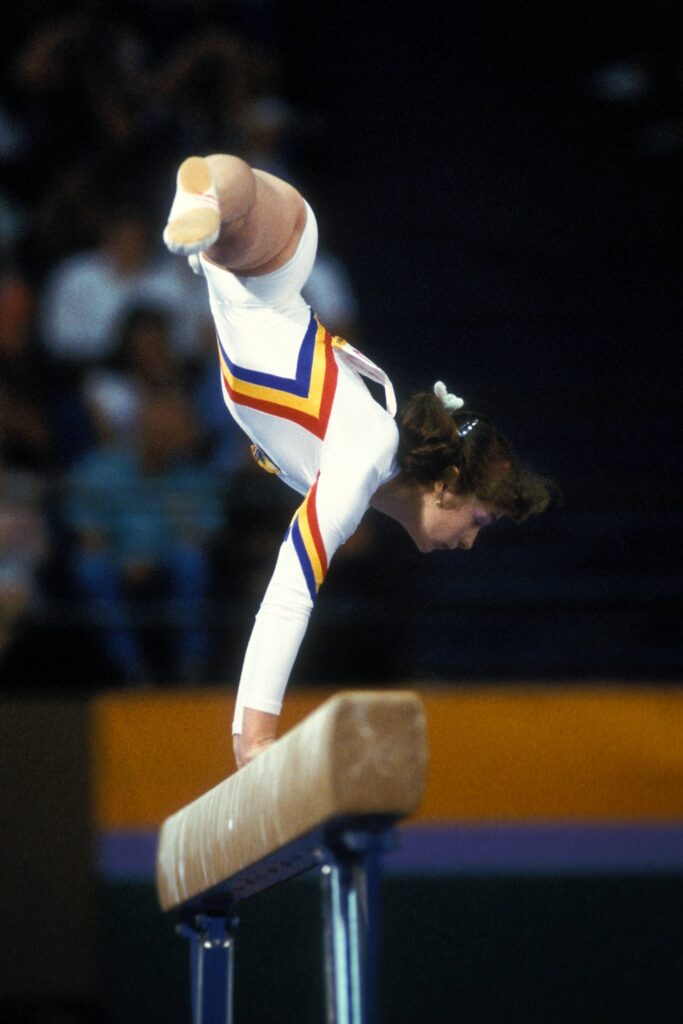

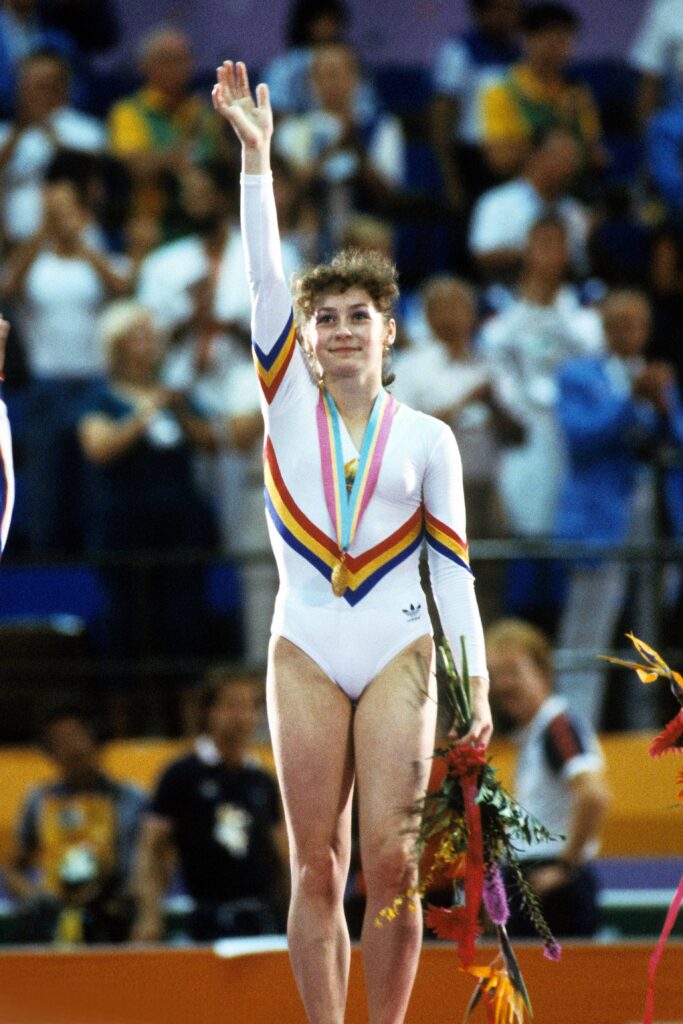

This lengthy profile of Ecaterina Szabó, published in Képes Sport (Sport in Pictures) in May 1990, offers a detailed firsthand account of life in Romanian gymnastics during the late 1970s and 1980s. The article, based on interviews conducted by Levente Deák for Romániai Magyar Szó (The Hungarian Voice of Romania), traces Szabo’s journey from a small village in Transylvania to Olympic glory at the 1984 Los Angeles Games, where she won four gold medals.

Notably, the article confirms Szabo’s actual birth date as January 22, 1968—making her 16 years old at the time of her Olympic triumph, not the older age sometimes claimed in contemporary sources. The narrative provides extensive detail about the grueling training regime at the Karolyi gymnastics school: wake-up calls at 6 AM, training sessions lasting until 10 PM as punishment, mandatory afternoon naps, and a schedule that prioritized gymnastics over traditional schooling.

As you’ll see, compared to today’s top gymnasts, Szabó competed non-stop, traveling to a total of 70 countries. It’s no wonder that, by the time the World Championships in 1985 rolled around, she “was simply exhausted.”

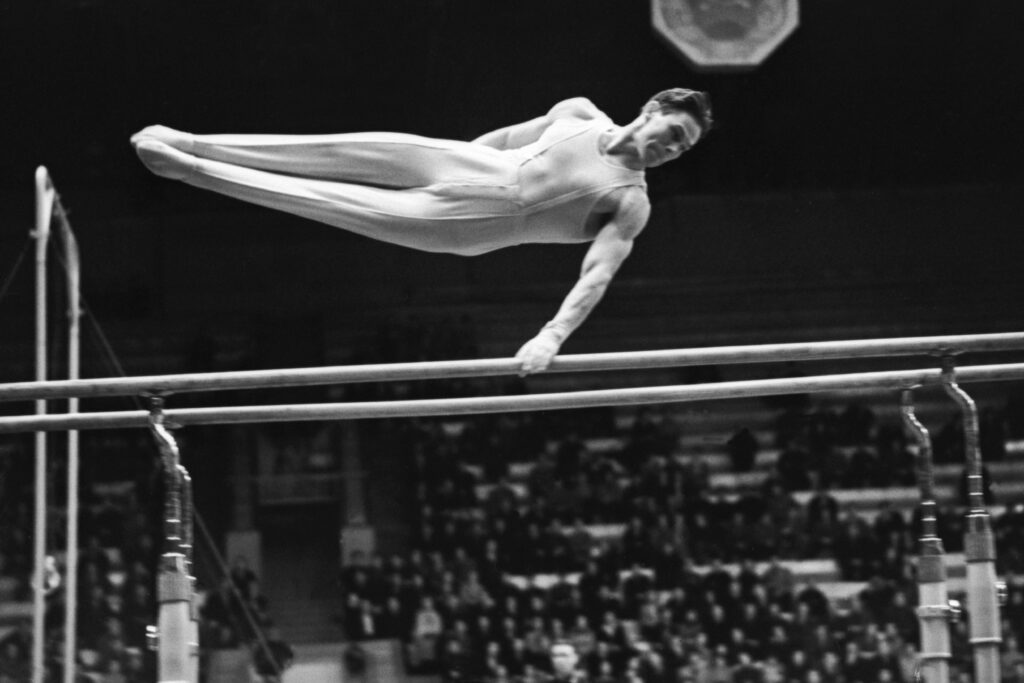

As was often the case at that time, gymnasts’ biographies were woven together with Béla Károlyi’s story. Throughout the piece, the writer includes several parenthetical statements that paint Béla Károlyi in a remarkably positive light, characterizing him as a dedicated coach who made tactical decisions in the best interests of his gymnasts.

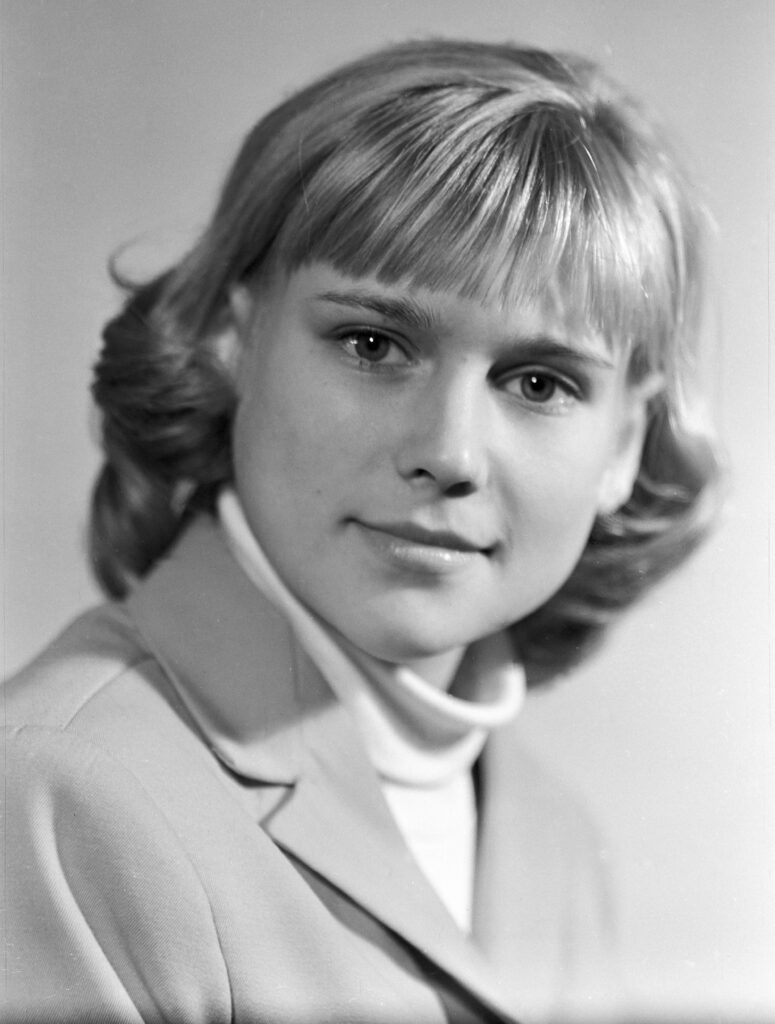

However, this generous portrayal omits crucial context that we know today: before the Károlyis were transferred to General School No. 7 in Deva, the Romanian government’s patience with the Károlyis was wearing dangerously thin. In March 1977, Teodora Ungureanu fled during training in Cluj, boarding a train to Onești. The Securitate intercepted her at the Târgu Mureș train station and escorted her to Bucharest. According to the Securitate report: “The gymnast gave as the reason for leaving the fact that she could no longer stand working with coach Béla Károlyi,” who “persecutes her baselessly.”

The situation continued to deteriorate during a tour of Spain in 1977. Securitate officer Ioan Popescu reported that Béla Károlyi “showed inappropriate conduct towards Nadia Comaneci and Teodora Ungureanu, consisting of swearwords, insults, even beating them, because their weight was unsuitable for the competition.” Ilie Istrate, a National Council for Physical Education and Sport (NCPES) instructor and Securitate informant, reported that “the girls were found weeping in their rooms because of hunger.” (See Olaru’s Nadia Comăneci and the Secret Police for more.)

Read against this historical background, Szabó’s account becomes all the more poignant—a testament to both her remarkable athletic achievements and the complex, often contradictory relationships that defined elite Romanian gymnastics in this era.

In many ways, this set of articles becomes Szabó’s way of reclaiming her story—from her erased Hungarian heritage to her falsified age, from the name she was given to the one she was born with (Katalin), and from the rewards she earned to those she never received.