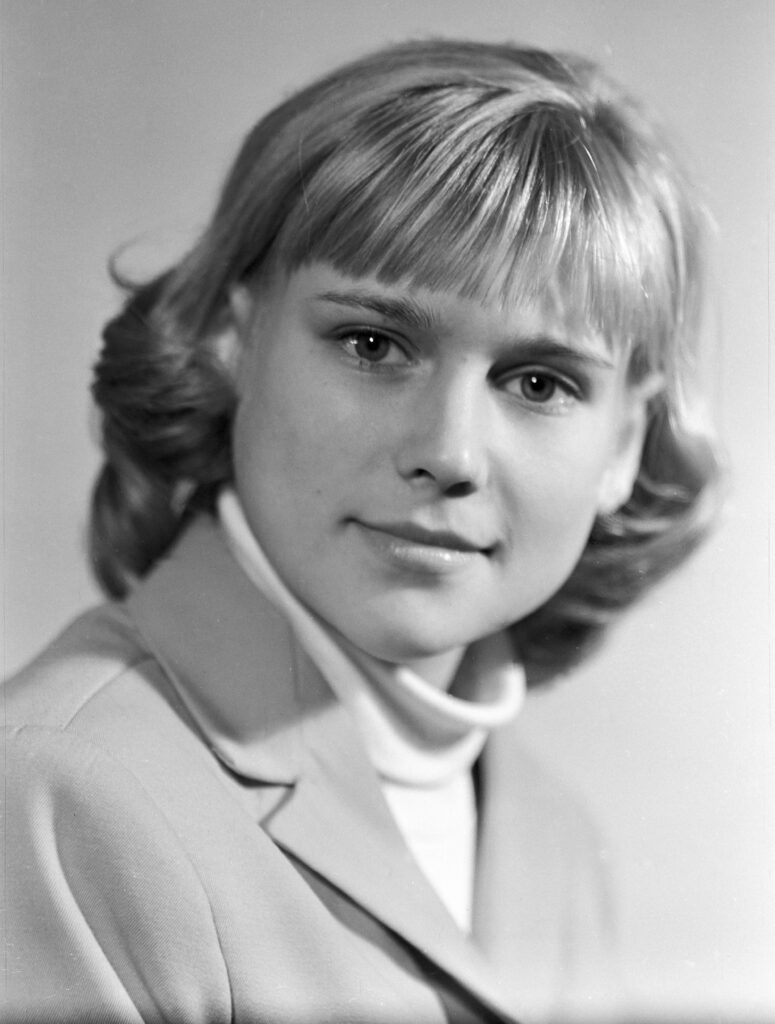

Among the brightest stars of Romanian gymnastics in the early 1980s, Lavinia Agache carved out a remarkable career despite controversies and heartbreak. Born February 11, 1968, in Onești—the same hospital that welcomed Nadia Comăneci into the world—Agache emerged as one of the era’s most decorated gymnasts, accumulating ten medals at major international competitions. Yet her path to prominence was shadowed from the start: Romanian officials altered her age, listing her birth year as 1966 instead of 1968. This deception allowed the thirteen-year-old Agache to compete illegally at the 1981 World Championships in Moscow, where she placed seventh all-around—two years before she would have been eligible under FIG’s minimum age of fifteen.

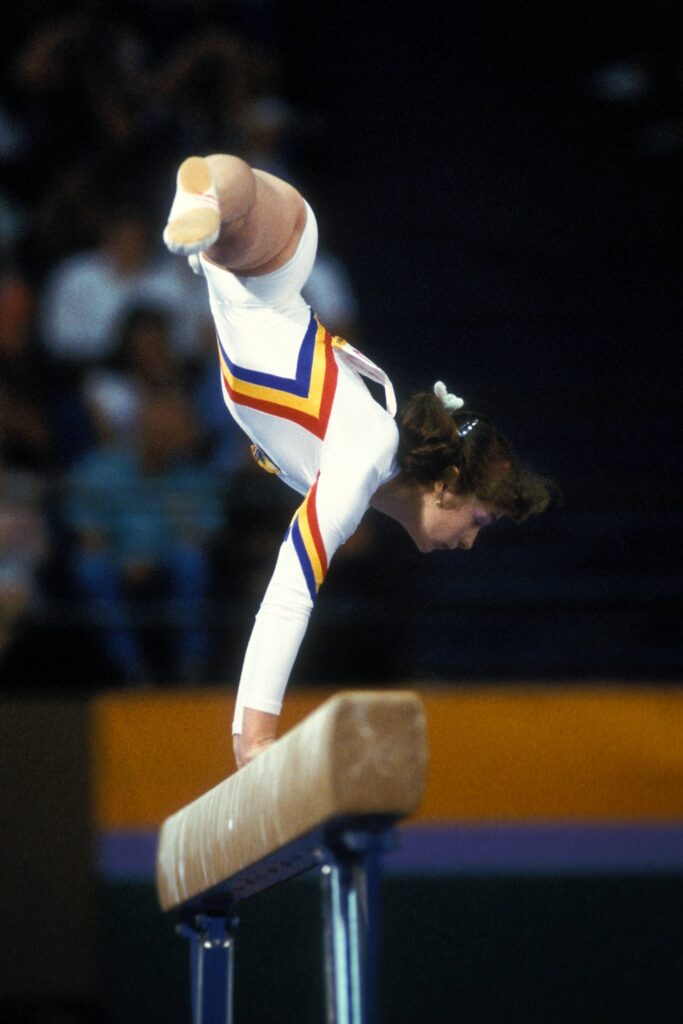

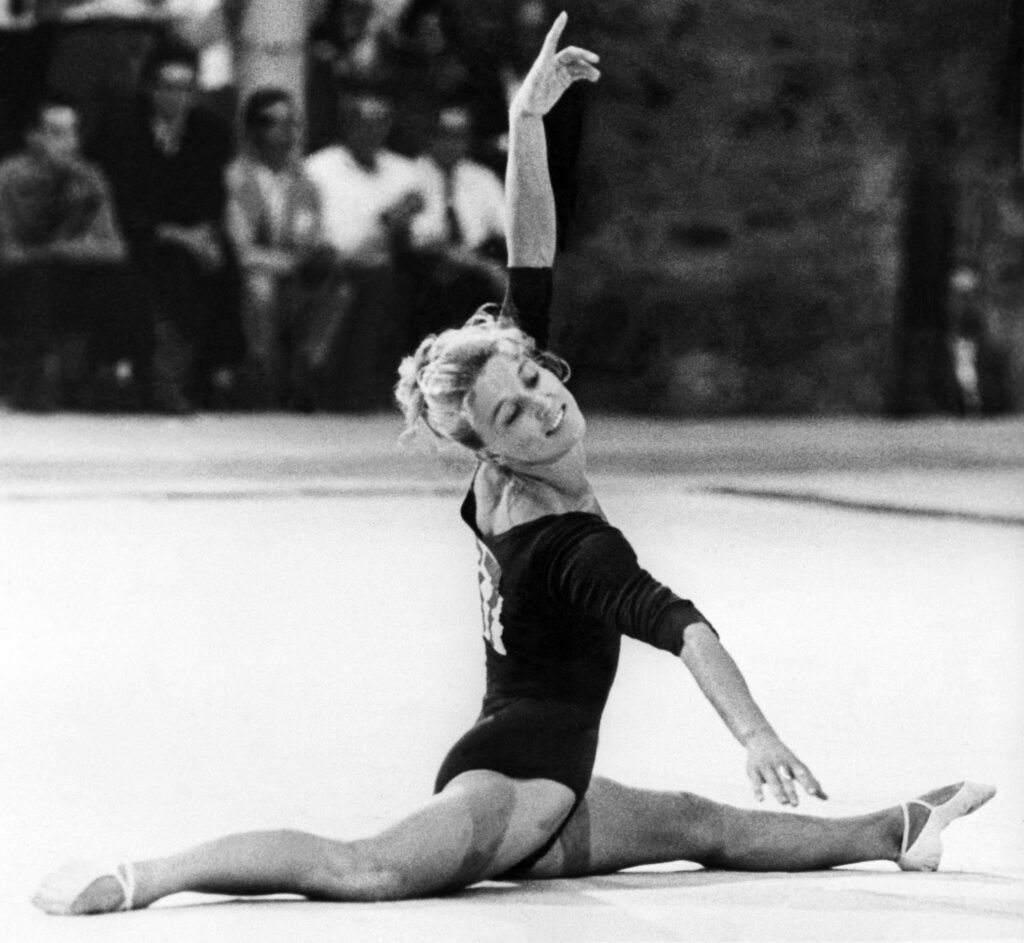

By 1983, Agache had established herself as a force in the sport, winning four medals at the European Championships in Gothenburg (including gold on balance beam and silver in the all-around) and three more at the World Championships in Budapest. She entered the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics as a legitimate contender for all-around gold, having finished third at the 1982 World Cup and consistently challenging teammate Ecaterina Szabó throughout their years training together at the Romanian national center in Deva.

First after compulsories, Agache’s Olympic dream disintegrated when a team doctor gave her a pill to combat jetlag. The next day, disoriented and lethargic, she fell four times during the optional round. The medication was legal, but its effects were devastating: Agache failed to qualify for the all-around final, watching from the sidelines as Szabó battled Mary Lou Retton for gold. What happened to Agache in Los Angeles—and the painful parallel she would later draw to Andreea Răducan’s 2000 Olympic ordeal, when a team doctor’s prescription cost the Romanian gymnast her all-around gold medal—forms a cautionary tale about the precarious intersection of medicine and athletic performance in elite gymnastics.

Here’s International Gymnast‘s piece on Agache from 2001, published before the age falsification scandal erupted in Romania in 2002.