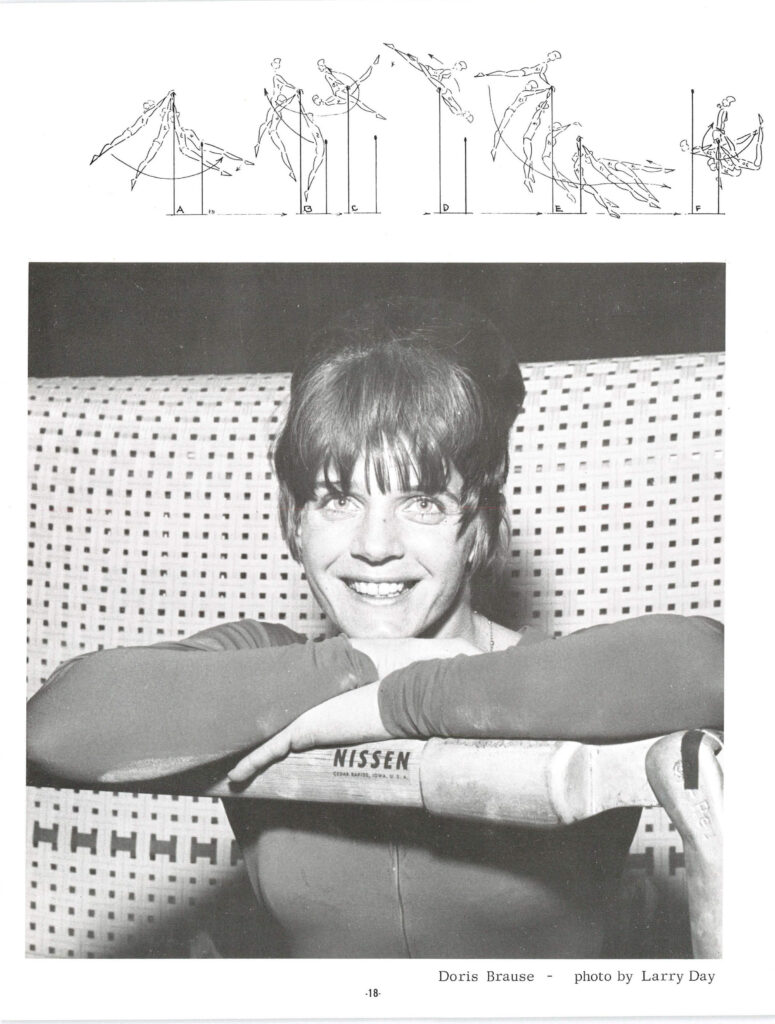

Recap: Doris Brause’s uneven bars routine created quite the sensation at the 1966 World Championships. When she received a 9.766 on bars, the crowd stopped the meet for over an hour, hoping to coerce the judges into raising her score.

The judges didn’t budge.

But uneven bars would never be the same again.

Here’s how Herb Vogel described her routine at the time:

“ZUSCHAUER-SKANDAL IN DER WESTFALENHALLE”-

“Das War Betrug!”

The literal translation, “Spectator-Scandal in Westfalen Halle!—It is a fraud!”

This front page, 2 inch bold type headline, points the description of the one hour and 3 minutes of irate spectator whistles, cat-calls and rhythmic stamping of feet:.. The longest, and perhaps now, the proudest hour in the gymnastic career of Doris Fuchs Brause, the “uncrowned Queen” of the uneven bars.

“Uncrowned” champion, but the true champion she is. The German Sports Telegram described her optional routine as a “brilliant, mistake free and fantastic endeavor.” To the German audience, the jury score, of 9.766 was simply not high enough to suit them. Their shouts, “Das War Betrug ! . . . it was a fraud! … still echo clearly.

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1966

What was so unique about this routine?

Here’s how it is typically explained: “Doris Brause was the first woman to ‘swing’ bars.”

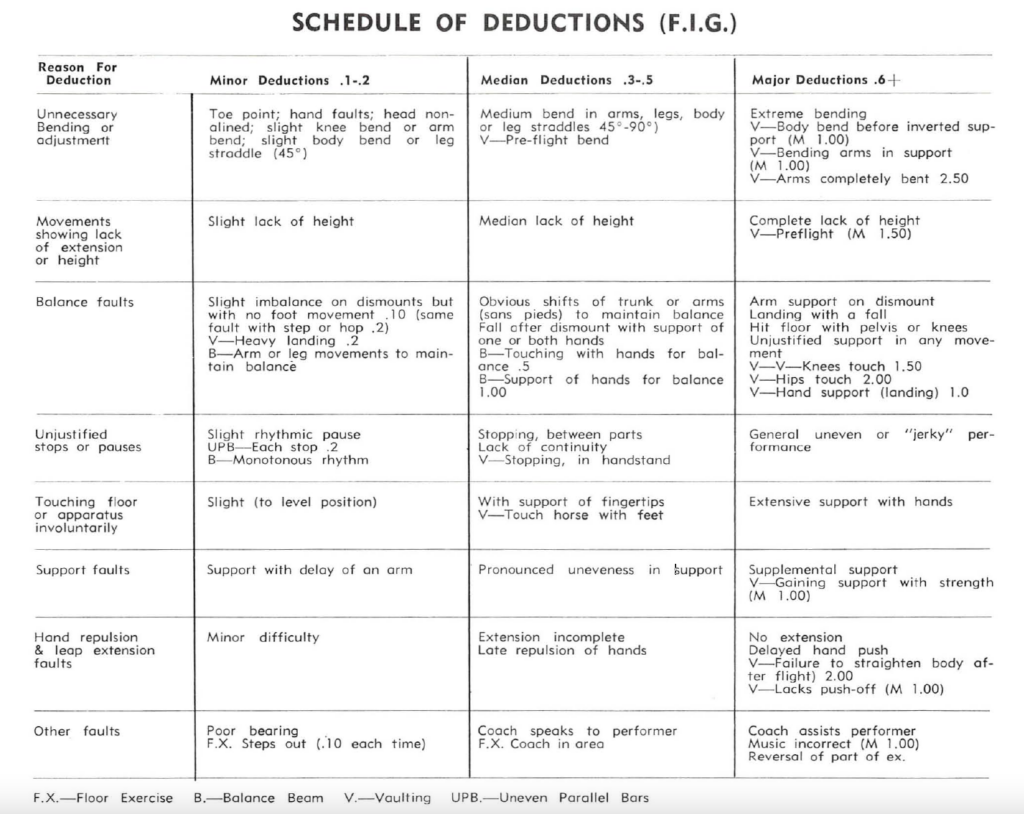

To understand what that means, you have to understand the gymnastics context. At the time, there was a 0.2 deduction for pauses on uneven bars.

To read the 1964 Code of Points, head over here.

But, but, but: The top gymnasts got away with taking pauses. As gymnastics historian Minot Simons II writes:

The secret of her success and the cause of the uproar was Brause’s technique of never stopping her routine on bars even for an instant. There was no pause to get ready for another move (or element, as they are called). There were no stops between parts of her routine. Hers was one continuous movement from beginning to send, as routines are nowadays. Thus, it was similar to men’s high bar routines. In Dortmund, gymnasts from the leading countries were allowed to make pauses or stops in their routines and they made them, as we shall see. Generally, there was only one such pause per routine, but it was enough to arrest the momentum and interrupt the harmony. Consequently, it was a sensation when one gymnast performed her routine swinging from bar to bar and from element to element without a stop.

Women’s Gymnastics: A History

That echoes what Herb Vogel wrote at the time:

From this writer’s coaching point of view, Doris’s routine presented an illusion of horizontal bar (men’s event) execution, in that it was free swinging and total. Her changes and transitions from bar to bar created the illusion that a low bar did not exist. While we coaches, and our stateside judges allow our girls unnecessary stops and stands of preparation . . . merely because the Europeans do so, Doris Brause “swings” bars. No pause to “get set” is ever made. Doris, as other forerunners of “swing is the thing” style, have been overly penalized by judges who read rules and simply interpret them as “words.”

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1966

But, but, but! She pauses!

Correct, there is a slight pause after her squat-on. However, her pause is much shorter and less pose-like than many of the pauses from other gymnasts.

But really, her routine composition is what’s unique.

My thought bubble

What’s truly unique is Brause’s choice of elements and the composition of her routine. It was vastly different from any other routine being competed.

Let’s break it down…

The clear hip

Brause was not the only gymnast to do a clear hip on the high bar, but the element was often followed by a back hip circle on the low bar. By doing a back hip circle on the low bar after a long-hang swing, the gymnast put the force into her hips.

Brause, on the other hand, took all the power generated from the long-hang swing after her clear hip, let go of the high bar, hung onto the low bar, transferred all the force into her hands, and kipped out. That was rare.

You can really see how much power she had. She had to really hold her toes out and exteeeeeeend the glide before her kip on the low bar.

The number of front hip circles

Again, Brause wasn’t the first gymnast to do a front hip circle on bars. But she did do many more front hip circles than most gymnasts at the time, which gave the impression that she never stopped circling around the bar.

Front hip circles to generate power

At a time when the bars were too close to do giants, she used the front hip circle as a way to generate power to do exciting skills, such as…

The Radochla Roll

For example, Brause used the front hip circle to launch herself into a front straddle somersault to the high bar, a skill named after Birgit Radochla. (Though, it was called the “Brause roll” for many decades.)

The Radochla roll was an exciting move. At the time, the men weren’t letting go of a bar, flipping upside down, and catching a bar again.

Side note: This skill would serve as the inspiration for the Comăneci salto, but instead of grabbing the high bar after casting on the low bar, Comăneci grabbed the same bar that she released.

Cast handstand to the high bar

It’s hard for modern gymnastics fans to understand this, but the showstopper in Brause’s routine was her cast handstand. If you watch the old bar routines, you’ll see that casting to handstand was rare — really rare — and Brause not only did it once; she did it twice. During her first cast handstand, she fluidly worked out of it as she swung over the high bar.

Cast handstand to half pirouette

Her second cast handstand was a cast handstand ½ pirouette into her dismount.

By doing a handstand pirouette on the high bar, she was able to give the impression that she was swinging bars like the men. She couldn’t do a giant on the uneven bars, but she could swing down from a handstand.

And doing a long hang swing out of a handstand was something unique and gave her tremendous power going into her dismount.

What did judges think at the time?

In his article for Modern Gymnast, Herb Vogel cites Irma Walter:

This report is not an exaggeration by an American writer for in support, German Judge, Irma Walter, is credited with this published news quote, “This (Brause’s) routine was the best of the competition. It (the routine) contained five of the highest difficulty parts and all were exacted without flaw. That is why I must award a score of 9.9, a 9.8 would not have been high enough.”

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1966

The New York Times had a similar quote:

A German judge who gave Mrs. Brause a 9.9 said: “I was considering giving her a perfect score. She was fantastic. I simply can’t understand how anyone could rate her 9.6.”

New York Times, Sept. 24, 1966

Note: From a gender perspective, it’s interesting that Brause’s routine didn’t call into question the 10.0 scoring system as it had with the men’s performances at the 1962 World Championships and the 1964 Olympics.

How was Brause scored?

- She received two 9.9s, two 9.7s, and one 9.6.

- One 9.9 was dropped, and the 9.6 was dropped.

- The average of 9.9+9.7+9.7 = 9.766.

Why wasn’t Brause’s routine properly scored?

There were several theories.

Theory #1: She was the victim of country bias.

This is a view that Brause herself espoused.

“I thought I deserved more than I got. Maybe I am just on the wrong team.”

New York Times, Sept. 24, 1966

Theory #2: Brause hadn’t made a name for herself in Europe.

I do not know why our American friends have not publicized this champion prior to the Championships for Doris Brause Fuchs was unknown to most of the judges and the “Case of Brause” could be an example in Europe and the world for the Americans start sooner and give more information the gymnastic press in Europe.

Dr. Joseph Goehler, VP of Deutscher Turner-Bund, Modern Gymnast, Nov. 1966

Theory #3: Brause’s routine was so unique that the judges didn’t know what to do with it.

One very definite impression of this writer, whose first contact with the routine was the film, is that it is quite possible that the judges did not know exactly what they were seeing. If this seems to be a naive concept, we can only suggest that other experienced teachers have expressed the same opinion when they had seen the exercise. for the first time. So much is thrown at you at once that it is difficult to remember the whole of it.

A. B. Frederick, Mademoiselle Gymnast, Sept./Oct. 1967

Where did this routine come from?

According to Minot Simons II, it’s the result of training on men’s high bar because she didn’t have a set of uneven bars at her gym:

Brause had long been an innovator on bars. Possibly because she did not have a set of uneven bars in her gym for a long time, she did her training on the men’s high bar. Therefore she got used to performing as the men do, swinging from element to element without stopping. This aspect of her routine had such an explosive impact on the crowd that they were outraged when she received a score of 9.766 instead of 9.9.

Women’s Gymnastics: A History

Note: Brause wasn’t the only female gymnast to be inspired by male gymnasts. In Věra 68 (2012), Čáslavská said that she looked up to the Japanese men and learned the uprise 1/1 release from them.

For what it’s worth, Čáslavská thought that Fuchs deserved to win the bar title in 1966:

The gold medal for uneven bars should have belonged to Doris Fuchs from the USA. We were all surprised by Kuchinskaya‘s victory, especially her.

Čáslavská, Cesta na Olymp

Zlatá medaile za bradla měla patřit Doris Fuchsové z USA. Všichni jsme vítězstvím Kučinské byli překvapeni, nejvíc ona sama.

By the way, formulaic bar routines have been a problem since the 1960s.

Are you annoyed by the absence of the Eagle catch in the Brause routine? Have you ever had the feeling that typical optional exercises on the uneven bars, yes even on an international level, are simply another kind of compulsory? The stock elements may be shuffled about in a number of interesting ways perhaps but they are there nonetheless. It is very refreshing to see a creative piece of work that defies the conformity of the Eagle catch, the superfluous kip, and the wraparound.

A. B. Frederick, Mademoiselle Gymnast, Sept./Oct. 1967

What about the spotter in the video?

Spotters were allowed. However, after the 1966 World Championships, they were supposed to stay outside the bars.

During a course for judges, Czechoslovak judge Alenu Tenterova noted:

The coach may stand outside the bars but should not stand between them. Otherwise 0.5 point penalty is imposed. We have come across such a situation, however, only at the latest World Championship in Dortmund, Germany; previous to it, the coach could have stood where he pleased.

Mademoiselle Gymnast, Sept./Oct. 1967

How far apart were the bars?

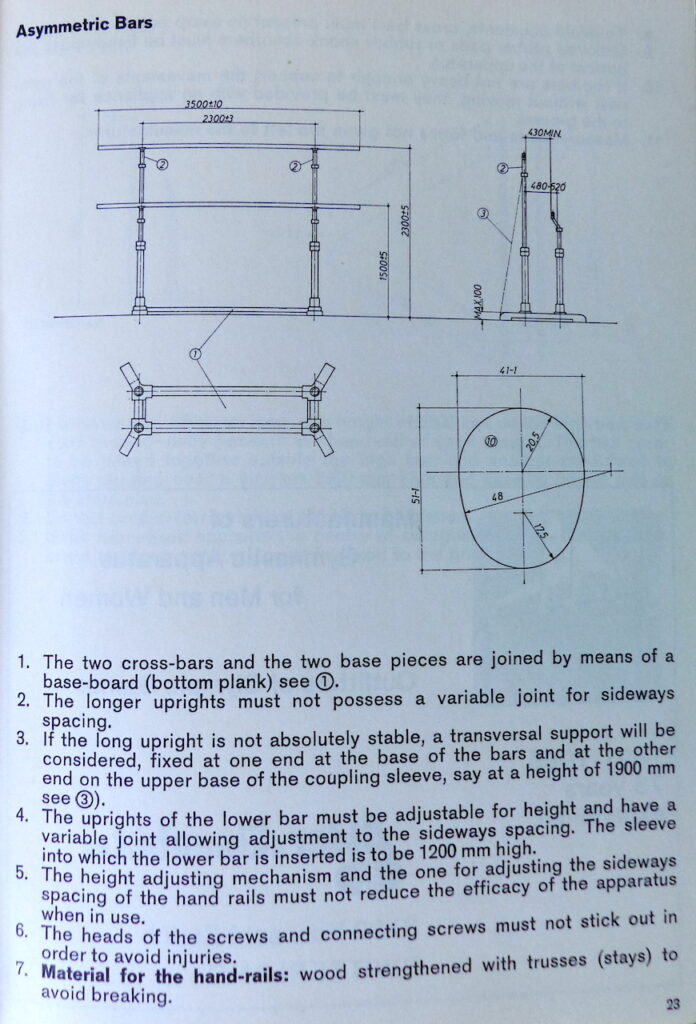

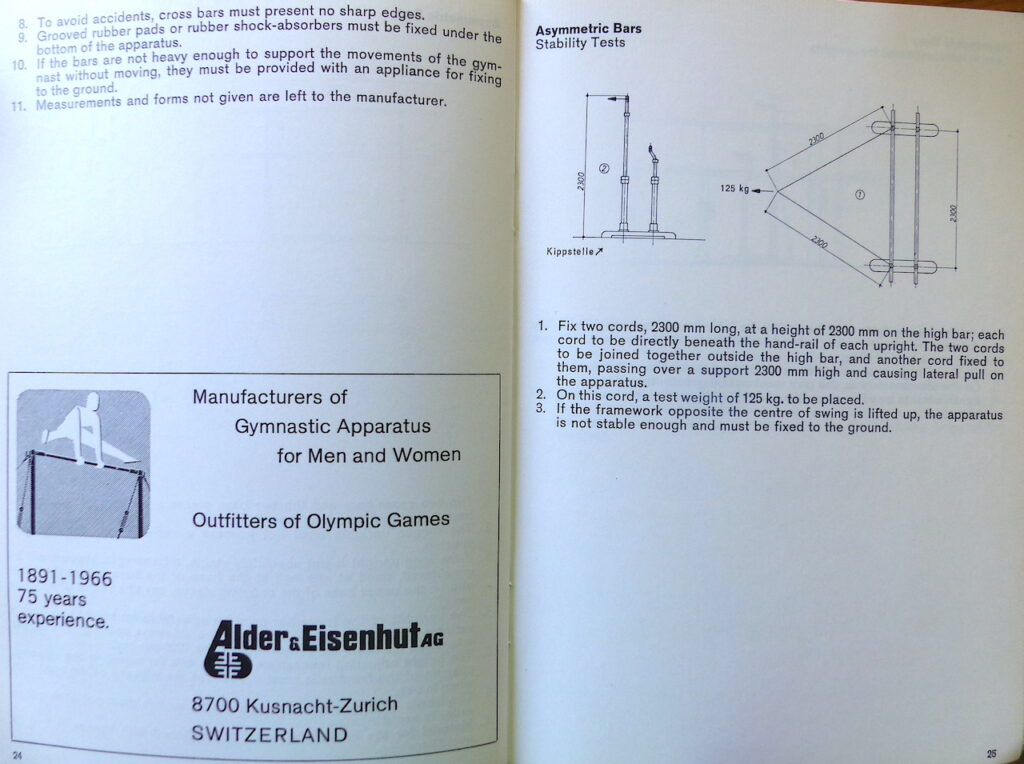

In this post, I kept talking about how gymnasts couldn’t swing giants in 1966. But just how close were the bars? Here are the apparatus guidelines from the FIG (1965):

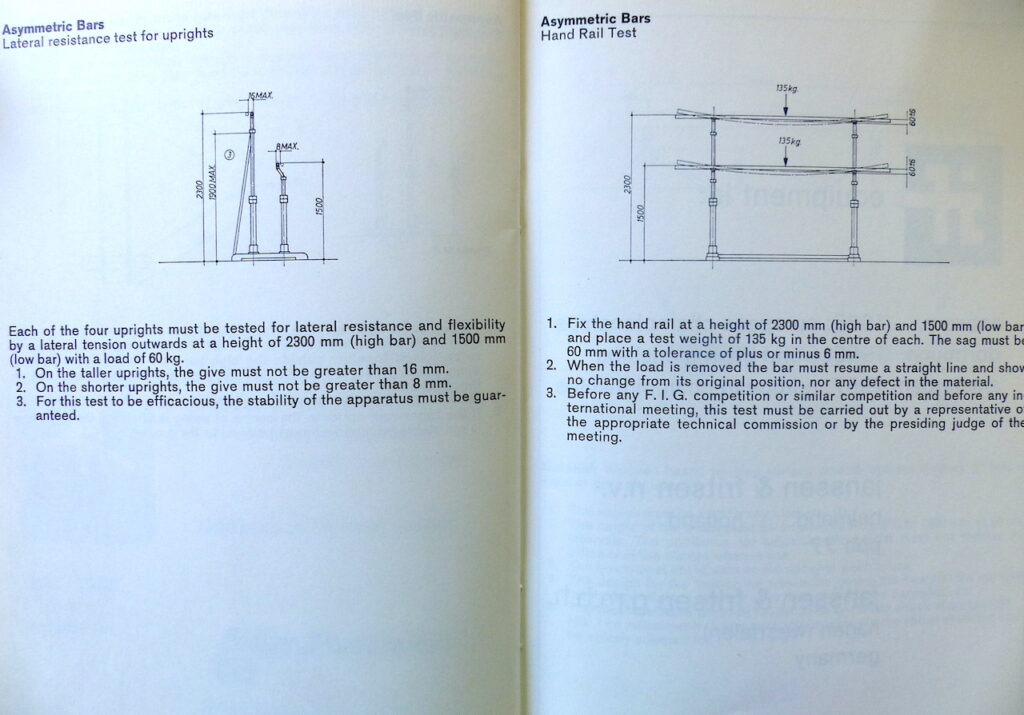

For all intents and purposes, the bars were men’s parallel bars with a brace for the taller upright. The width of the bars had to be a minimum of 43 cm (16.93 in.) and a maximum of 52 cm (20.47 in). That’s really close.

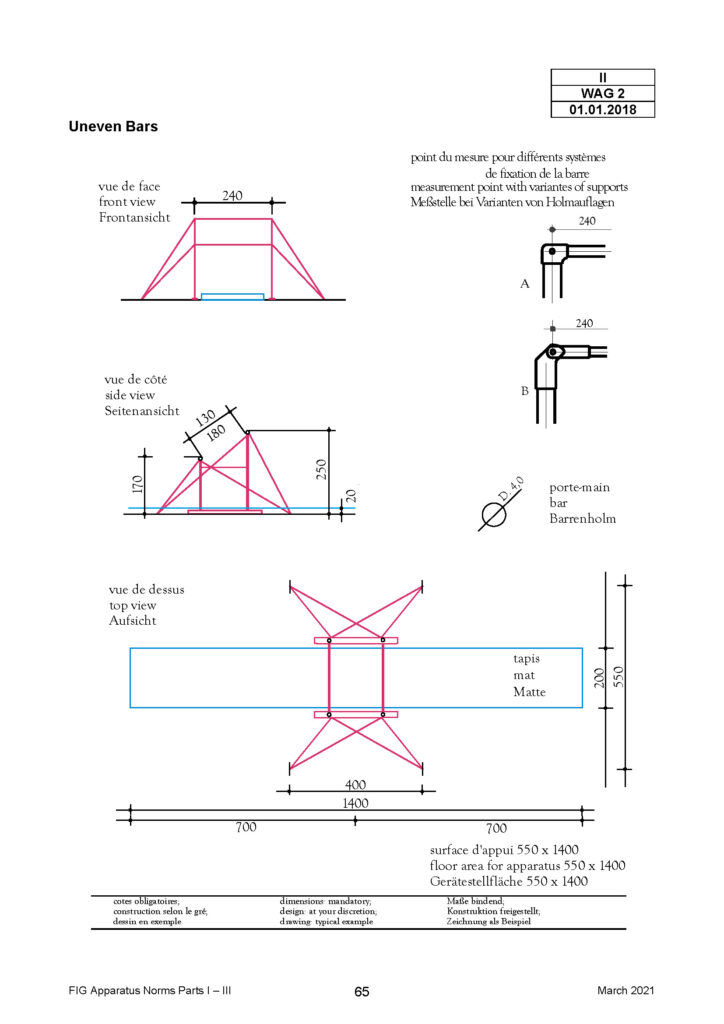

We no longer measure the width in this manner. We measure it as the distance from the high bar to the low bar. That distance is now between 130 (51.18 in.) and 180 cm (70.87 in.).

In 1966, the distance from the high bar to the low bar would have been about 90 cm (35.43 in.) to 95 cm (37.40 in.), depending on the setting. So, roughly half of today’s distance.

Compared to today’s apparatus norms, both the high and low bars in 1966 were about 20 cm (7.87 in.) lower.

Safety note: Because the gymnasts were essentially competing on a set of parallel bars, there were extensive tests that needed to be done:

It’s quite impressive that these bars were able to accommodate the power of Doris Brause’s routine.

Remember how I said that uneven bars would never be the same again? I wasn’t just talking about the composition of the routines. I was also talking about the physical apparatus.

The 1966 World Championships would be the last FIG-sanctioned event that would utilize these bars. At the 1967 European Championships, the bars changed. We’ll take a look at those bars when we get to that competition.

Because Brause’s routine stopped the meet, the judges had a long day. In the next post, we’ll quickly look at judging fatigue.

Until then…