The gymnastics community was buzzing about the women’s competition in Dortmund in 1966. The Soviet Union brought a younger team to the competition, which raised several questions.

Could the Soviets continue to win the team competition?

Could stalwarts like Čáslavská and Latynina continue to dominate the sport?

*Insert dramatic music*

Let’s find out…

As always, this is a long post, so here are some links to help you jump around:

Historical Context | Gymnastics Context | The USSR’s Change of Strategy | Video Footage | Team Competition | All-Around Competition | Event Finals | Judging Controversy

The Basics

156 Gymnasts

Tuesday, September 20: Opening Ceremonies

Thursday, September 22: Compulsories

Saturday, September 24: Optionals

Sunday, September 25: Event Finals

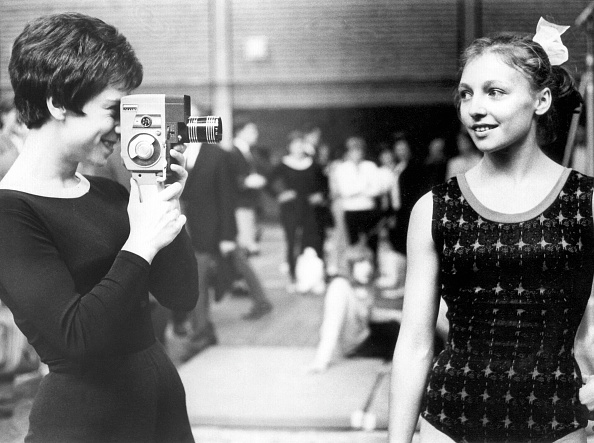

Photo: Věra Čáslavská, Getty Images

Historical Context

Gymnastics doesn’t happen in a vacuum. So, here’s some information to get you situated.

The Space Race between the USSR and the USA continued.

- The Soviet Union landed Luna 9 on the Moon

- The Soviet Union’s Luna 10 became the first spacecraft to orbit the Moon

- Lunar Orbiter 1 was the first U.S. spacecraft to orbit the Moon.

The Vietnam War raged on, and so did the protest movement.

- March 25-26: the National Coordinating Committee to End the War in Vietnam helped sponsor the “Second International Days of Protest.”

- On April 12, 1966, 29 B-52s bombed Northern Vietnam, trying to break the supply line that was nicknamed the “Ho Chi Minh Trail.”

- On July 3, protesters demonstrated against the U.S. war in London outside the U.S. Embassy.

- On July 7, the European Communist nations agreed to send volunteers to North Vietnam if the North Vietnamese government requested such support. The nations included were the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania.

Czechoslovakia had its own growing protest movement. In 1966, journalists, students, and writers called for the end of censorship laws.

Civil unrest and mass racial violence were boiling over in the United States.

- Examples: the Hough riots in Cleveland, the Division Street riots and the Marquette Park riot in Chicago, the Hunters Point riot in San Francisco

- Compton’s Cafeteria riot in San Francisco was one of the first LGBTQ+-related riots

Not your type of history? Here’s some more information…

- Star Trek and Batman debuted on TV.

- The Australian dollar was introduced on February 14, 1966, officially replacing the Australian pound.

Gymnastics Context

The gist

Čáslavská was the clear favorite going into Worlds. She even had a 10.0 under her belt.

But, but, but

Čáslavská had a new group of Soviet gymnasts to contend with.

The details 👇

Reigning Olympic Champion

- The Soviet Union (Team)

- Věra Čáslavská (AA)

Reigning European Champion (1965)

- Věra Čáslavská (AA)

- In fact, Věra Čáslavská won all five gold medals at the 1965 European Championships.

Czechoslovak Nationals (June 1966)

- 1. Věra Čáslavská (78.95) 2. Jaroslava Sedláčková (77.25) 3. Marianna Krajčírová (77.15)

- During the Czechoslovak Nationals, Čáslavská scored a 10.0 on her optional floor routine.

Soviet Competition Update

- USSR Nationals (December 1964)

- 1. Larisa Petrik 37.55 2. Larisa Latynina 37.50 3. E. Tiazelova 37.40

- USSR Nationals (June 1965)

- 1. Polina Astakhova 76.05 2. Natalia Kuchinskaya 75.90 3. Nikolaeva 74.55

- Petrik didn’t compete due to injury.

- Latynina didn’t compete because she was “tired after the European cup and exhibition in Italy” (Modern Gymnast, Sept/Oct 1965)

- USSR Nationals (November 1965)

- 1. Polina Astakhova 75.45 2. Natalia Kuchinskaya 75.30 3. Larisa Latynina 74.75 4. Dzamukashvili 74.55 5. Elena Volchetskaya 74.50

- USSR Worlds Qualifications (July 1966)

- 1. Natalia Kuchinskaya 77.85 2. Larisa Petrik 76.45 3. Polina Astakhova 76.10

Other Notes

- Ikeda Keiko tore her Achilles in November 1964, shortly after the Olympics.

- In a dual meet between the USSR and Japan in October of 1965, Zinaida Druzhinina won (38.85), and Natalia Kuchinskaya was second (38.50).

- The 1964 Code of Points is available here.

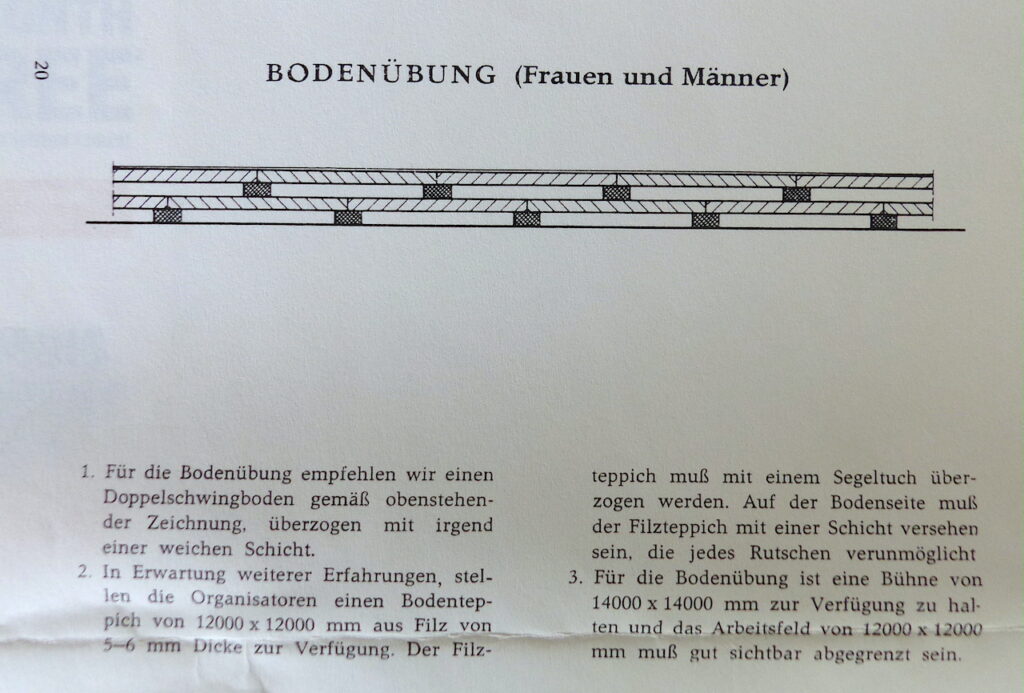

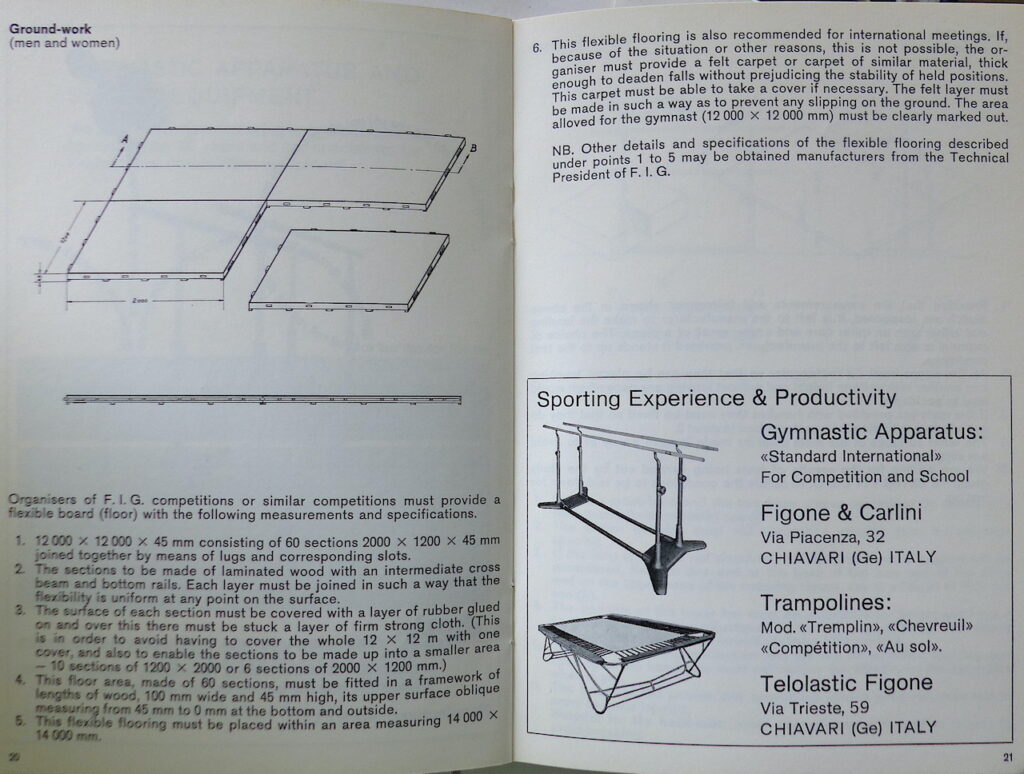

The Double Swing Floor

At the 1966 World Championships, the gymnasts competed on the double flex floor (sometimes called the “double swing floor” or the Reuther floor). It was essentially two floorboards sandwiched together with small wooden inserts between the layers. (Eventually, there would be foam blocks and rubber balls between the layers.) You could see it as a precursor to the modern spring floor. Though it was meant to flex in a way similar to the Reuther boards used on vault, it did not have as much “give.”

This type of floor appeared in the 1960 Apparatus Dimension booklet. However, it did not become mandatory for FIG events until the 1965 booklet.

According to Hardy Fink, similar ones were made with the collaboration of Spieth and Senoh for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and by Jansen-Fritsen for 1965 Europeans.

The Soviet Union’s Changing of the Guard

Latynina: The Legend

Latynina was the 1956 and 1960 Olympic all-around champion, as well as the 1958 and 1962 World all-around champion.

Finishing Second

After losing the all-around title to Čáslavská at the 1964 Olympics, Latynina came home only to finish second to Larisa Petrik at the Soviet Nationals in 1964. Petrik was 15 at the time.

Taking Teenagers to the 1966 Worlds

For years, the Soviet Union had relied on 20-something or 30-something gymnasts at international competitions. That changed in 1965, when teenager Larisa Petrik competed alongside Latynina at the 1965 European Championships.

One year later, the Soviets brought a whole bunch of teenagers to Worlds:

- Three 17-year-olds (Kuchinskaya, Petrik, and Kharlova)

- One 18-year-old (Druzhinina)

- A 29-year-old (Astakhova)

- A 31-year-old (Latynina)

That was quite the change for the reigning Olympic champions.

Note

Teenage gymnasts weren’t brand new for women’s gymnastics. For example, Čáslavská was 16 in 1958 when her team won silver, as was Marianna Krajčírová in 1964. What mattered to the gymnastics community was that the Soviets were changing their strategy.

My thought bubble

The Soviet Union was smart. They probably could have fielded a team of teenagers, but they opted for a phased approach.

Gymnastics is big on tradition. So, the Soviet team brought some of their stalwarts (Latynina and Astakhova) in addition to their next wave of younger gymnasts. That way, judges saw familiar faces and weren’t shocked by a team of teenagers.

Here’s what was written in the Revue EP&S about this strategy:

The Russians presented, as with the men, but there much more with a calculating spirit, four young gymnasts (three are 17 years old, one is 18 years old) and two former champions Astakhova. 30 years old, and Latynina, 32 years old. This tactic paid off because the judges, alas! are influenced by names and the same faults are not penalized in the same way depending on whether the gymnast’s name is Latynina or Letourneur. This was particularly evident on vault and uneven bars.

EP&S, n. 83, Nov. 1966

Les Russes ont présenté, comme chez les hommes, mais là beaucoup plus avec un esprit calculateur, quatre jeunes gymnastes (trois ont 17 ans, une a 18 ans) et deux anciennes championnes Astakhova. 30 ans, et Latynina, 32 ans. Cette tactique s’est avérée payante car les juges, hélas ! sont influencés par les noms et les mêmes fautes ne sont pas pénalisées de la même manière selon que la gymnaste s’appelle Latynina ou Letourneur. Ce fut particulièrement flagrant au saut de cheval et aux barres asymétriques.

A Note about Age Requirements

When U.S. gymnast Cathy Rigby made the 1968 Olympic team at the age of 15, the New York Times reported:

International gymnastics rules state that, in general, competitors must be 18 years old. In exceptional cases, the rule says, a competitor under 18 will be authorized to compete but only under the responsibility of the sports federation of his or her country.

October 10, 1968

Video Footage

This footage takes you through compulsories, optionals, and the event finals. It’s great because it includes some of the routines from the non-medalists.

For example, you can see Erika Zuchold performing her eponymous bar transition at the 13:01 mark.

Kuchinskaya on UB (3:04): Notice the amplitude. Even the way she jumps for her kip on the low bar.

And I love that there are glimpses of the future of gymnastics. For example, her seat-circle transition from high to low has the makings of a Pak salto. (BTW, a seat-circle to the low bar is still in the Code of Points.)

Čáslavská on UB (4:00): Her cast 1/1 to uprise 1/1 was incredible. Keep in mind that some men were competing the uprise 1/1 at the time. In fact, Ono Takashi performed the skill during event finals at the 1964 Olympic Games, as did Čáslavská.

In Věra 68 (2012), Čáslavská said that she looked up to the Japanese men and learned the uprise 1/1 release from them.

Mitsukuri on UB (4:50): Even though she pauses before the skill, I love how she transitions into her cut catch. It gives the impression that she did a front flip.

Čáslavská on BB (5:53): In 1964, her back walkover series was rare. But two years later, it was commonplace. (See, for example, Kuchinskaya’s routine.)

Kuchinskaya on BB (7:42): It was rare for women to show strength elements in their routines, yet Kuchinskaya did a press handstand and a press down.

The stag handstand position in her second back walkover was iconic.

Čáslavská on FX (10:05): Čáslavská performed to “Vltava,” a piece by Bedřich Smetana about the river in Bohemia. (Thanks to Twitter for helping me identify this piece.) The routine is full of classic Čáslavská combinations: aerial cartwheels + an illusion, her back handspring to her knees.

Kuchinskaya on FX (12:03): She opened with a full, a pass that many of the men opened with, as well.

But the skill that stood out was her layout ½ step out, which she danced out of. In the February 1967 issue of Modern Gymnast, the British coach Pauline Prestridge wrote: “Kouchinskaia’s back-flip ½ turn jump (on the rebound ) to splits was also an eye-catcher.”

Keep in mind that it was rare for women to perform two twisting passes in one routine at the time.

Druzhinina on FX (14:10): This is the routine that had everyone talking. During finals, this routine received a 9.933, the highest score of the meet.

Here’s what stands out to me:

- How her dance enhanced Franz Lehár’s “Meine Lippen, sie küssen so heiß.”

- How she embodied the charismatic character of Giuditta, a night club dancer in North Africa.

- Her amplitude on everything, even her aerial cartwheel at the beginning

- Her back full (first pass) finished with a tight arch instead of a pike

- (Let’s ignore her crooked tumbling.)

Elements not featured in the videos:

In the February 1967 issue of Modern Gymnast, Pauline Prestidge, the British team’s coach, reported seeing the following skills:

- An unidentified Soviet gymnast training a half on + full off. The vault was not performed in competition.

- The Soviets performed: Yamashitas (Petrik, Karlova), Handsprings (Druzhinina, Astakhova), Half on + half offs (Latynina, Kuchinskaya)

- Zuchold did a “back flip” on beam

- I take that to mean a back handspring.

Team Competition

The women’s competition was a nailbiter until the very last routine. So good!

The Soviet Union started the optionals portion of the competition with the lead. Here were the standings after the compulsories:

| Country | Comp. Score | Final Ranking |

| 1. Soviet Union | 191.358 | 2 |

| 2. Czechoslovakia | 190.995 | 1 |

| 3. Japan | 190.894 | 3 |

| 4. East Germany | 187.494 | 4 |

| 5. Hungary | 186.527 | 5 |

| 6. France | 183.193 | 7 |

| 7. Bulgaria | 182.694 | 8 |

| 8. United States | 182.360 | 6 |

| 9. Sweden | 181.429 | 9 |

| 10. West Germany | 181.093 | 10 |

| 11. Poland | 180.526 | 11 |

| 12. Yugoslavia | 174.125 | 13 |

| 13. Canada | 173.461 | 15 |

| 14. Norway | 173.127 | 12 |

| 15. Netherlands | 172.660 | 14 |

| 16. Cuba | 168.894 | 20 |

| 17. South Africa | 168.693 | 19 |

| 18. Israel | 168.662 | 16 |

| 19. New Zealand | 168.459 | 18 |

| 20. Finland | 166.061 | 21 |

| 21. Great Britain | 165.293 | 17 |

| 22. Austria | 161.228 | 22 |

After the first rotation, Czechoslovakia had taken control of the lead.

After Rotation 1

| Team | Event | Score | Running Total |

| 1. Czechoslovakia | UB | 48.166 | 239.161 |

| 2. Soviet Union | VT | 47.699 | 239.057 |

But the pendulum swung back and forth between the Soviet and Czechoslovak teams during the next two rotations.

After Rotation 2

| Team | Event | Score | Running Total |

| 1. Soviet Union | UB | 48.109 | 287.256 |

| 2. Czechoslovakia | BB | 47.933 | 287.094 |

After Rotation 3

| Team | Event | Score | Running Total |

| 1. Czechoslovakia | FX | 48.532 | 335.626 |

| 2. Soviet Union | BB | 48.032 | 335.288 |

Heading into the final rotation, the Czechoslovak team had a 0.338 advantage.

The Soviet strategy: According to Herb Vogel in Modern Gymnast (Dec. 1966), the team shuffled their line-up and sacrificed Zinaida Druzhinina as the lead-off gymnast.

The logic: If Druzhinina got a high score, the scores of the gymnasts following her would be pushed up.

The outcome: Druzhinina received one 9.90 and one 10.00. Her final score of 9.800 ultimately boosted Petrik’s score.

(Unfortunately, putting Druzhinina early in the lineup may have cost her the gold medal on floor. More on that below.)

But, but, but: Though the Soviet team on floor outscored the Czechoslovak team on vault, it was not enough. The Czechoslovaks won the team gold medal and ended the Soviet Union’s winning streak at Worlds (1954, 1958, 1962).

Final Standings – 1-6

| Team | Vault | Bars | Beam | Floor | Total |

| 1. Czechoslovakia | 383.625 | ||||

| C. | 47.632 | 48.066 | 47.531 | 47.766 | 190.995 |

| O. | 47.999 | 48.166 | 47.933 | 48.532 | 192.630 |

| 2. Soviet Union | 383.587 | ||||

| C. | 47.364 | 48.098 | 47.598 | 48.298 | 191.358 |

| O. | 47.699 | 48.199 | 48.032 | 48.299 | 192.229 |

| 3. Japan | 380.923 | ||||

| C. | 47.300 | 48.397 | 47.265 | 47.932 | 190.894 |

| O. | 47.299 | 48.532 | 46.299 | 47.899 | 190.029 |

| 4. East Germany | 377.818 | ||||

| C. | 47.298 | 47.033 | 46.799 | 46.364 | 187.494 |

| O. | 47.697 | 47.898 | 46.798 | 47.931 | 190.324 |

| 5. Hungary | 373.889 | ||||

| C. | 45.832 | 46.998 | 47.199 | 46.498 | 186.527 |

| O. | 46.332 | 46.998 | 47.299 | 46.733 | 187.362 |

| 6. United States | 367.620 | ||||

| C. | 45.532 | 45.799 | 45.231 | 45.798 | 182.360 |

| O. | 46.699 | 45.897 | 45.999 | 46.665 | 185.260 |

*Modern Gymnast had some data entry issues for the individual event scores for places 7 and beyond.

Final Standings – 7-22

| Country | Comp. | Opt. | Final |

| 7. France | 183.193 | 183.225 | 366.418 |

| 8. Bulgaria | 182.694 | 183.661 | 366.355 |

| 9. Sweden | 181.429 | 181.662 | 363.091 |

| 10. West Germany | 181.093 | 181.859 | 362.952 |

| 11. Poland | 180.526 | 182.394 | 362.920 |

| 12. Norway | 173.127 | 179.962 | 353.089 |

| 13. Yugoslavia | 174.125 | 175.528 | 349.653 |

| 14. Netherlands | 172.660 | 176.328 | 348.988 |

| 15. Canada | 173.461 | 172.693 | 346.154 |

| 16. Israel | 168.662 | 174.660 | 343.322 |

| 17. Great Britain | 165.293 | 173.360 | 338.653 |

| 18. New Zealand | 168.459 | 169.893 | 338.352 |

| 19. South Africa | 168.693 | 166.761 | 335.454 |

| 20. Cuba | 168.894 | 165.026 | 333.920 |

| 21. Finland | 166.061 | 166.295 | 332.356 |

| 22. Austria | 161.228 | 168.825 | 330.053 |

Team USA

Training camp

To make up for a lack of a centralized training environment, the team had a pre-Worlds training camp in the Catskills.

Impressive

The U.S. women impressed the world by moving from ninth at the 1964 Olympics to sixth place.

Even more impressive: They had to rely on 5 gymnasts in a 6-up-5-count format

- Linda Metheny couldn’t compete because of a back injury

- Donna Schaenzer, the alternate, was also injured

- Joyce Tanec, the second alternate, had to jump in and compete.

- Dale McClements Flansaas was nursing a knee injury. Then, she hurt her other knee in competition, leaving the U.S. with five counting scores.

- She hurt her knee while trying to stick the compulsory vault: A handspring with a 1/4 turn and sideways landing. (Not the FIG’s best idea.)

- She would “never compete again because it [had] weakened the knee beyond repair” (Modern Gymnast, Jan. 1969).

A sad tangential note

Hali Sheriff, a rising star, passed away at the age of 14 in a plane crash.

Team Canada

Trending: Training camps

- To make up for the lack of a centralized system, countries like the U.S. and Canada had long training camps.

- Team Canada trained in Toronto prior to the 1966 Worlds.

- This was a challenge for women with home and work commitments. Elsbeth Austin was unable to train regularly with the team.

- Marilyn Minaker fell on bars, hampering her performance at Worlds

Compulsory woes

During compulsories, the Canadian team followed the Soviet team. Their coach, Marilyn Savage, believed that that is why they couldn’t score above a 9.0.

Vaulting struggles

Whereas the Canadian men were strong on vault, the Canadian women struggled, “especially in on-flight and landings!” (Modern Gymnast, January 1967).

Music problems

At the 1962 Worlds, the Canadian team needed to borrow the Polish pianist. At the 1966 Worlds, they needed help from the Bulgarian pianist.

Spain

Gymnastics Royalty

Ana Elena Sánchez Blume, the niece of Joaquim Blume, joined Maribel Jiménez in Dortmund. (Joaquim Blume was the European champion in 1957. He died in a plane crash in 1959.)

It would be the first time that Spain sent gymnasts to the World Championships.

Paraphrasing an interview from El eco de Canarias (Sept. 24, 1966)…

Few gymnasts: When asked why there were only two gymnasts, they said that there wasn’t much to choose from. In addition, gymnasts had to pass a series of tests in order to participate.

The state of women’s gymnastics in Spain: It’s not growing. It’s the same as always. Spanish women simply aren’t interested in gymnastics.

The challenges: They don’t earn anything. In fact, they have to pay out of their own pocket. The federation pays for their uniforms for major meets, but their daily workout gear is at their expense.

Team Great Britain

The British women sent their first full team to the World Championships in 1966, but they had problems along the way.

18-year-old Ann Simmons was unable to compete because of a dislocated shoulder. Linda Parkin replaced her, but she had not been doing gymnastics for the three months prior to the competition in Dortmund (Coventry Evening Telegraph, Sept. 22, 1966)

Pauline Prestidge said very little about the British performances at the competition. She stated:

What a wonderful experience these championships are, but what a lot of preparation we must make for the next one. Our gymnasts from Britain must train harder and more efficiently than ever before, with more care and thought of the basic elements. It will be a difficult task, with so many obstacles to surmount, but it must and will be done.

Modern Gymnast, Feb. 1967

The All-Around Competition

Reminder: There wasn’t a separate all-around competition as there is today. At the same time that gymnasts were competing for the team title, they were competing for the all-around title. Their all-around totals were the sum of their optional and compulsory routines.

The gymnastics community saw it as a battle of the veterans vs. the youth. And the youth were ready.

Petrik, Russia’s National Champion, and Kuchinskaya, U.S.S.R. World Team Trial Champion, had the skill, the class, and the “cocky” attitude necessary to get the job done.

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1966

Petrik was the first contender to falter on compulsory uneven bars.

Petrik was the first to falter and was forced to repeat her uneven bar compulsory. The “repeat” held a slight tinge of fear and as she moved through the previously missed compulsory part she dropped her veil of poise momentarily, “bobbled”, recovered expertly and went on to sell the dismount to its fullest worth. A slight mistake, but enough.

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1966

Gymnasts could repeat their compulsory routines, but it was dangerous. Exhibit A: East Germany’s Trensinger on beam.

Trensinger, after an almost faultless exercise decided to taken the second attempt allowed-she had had a slight overbalancing at one point-she mounted the beam for this second attempt—remember the first is not marked when opting for this privilege!—but, oh, dear, the beam and Trensinger were at war with one another, for as much as she tried, the worse she became, until finally she gave up in despair. What a tragedy for a girl who could have gained 9.4 or 9.5 to receive a mere 4.

Modern Gymnast, Feb. 1967

Here were the scores after compulsories.

Standings after Compulsories – Top 10

| Gymnast | Country | Comp. Score | Final Rank |

| 1. Čáslavská | TCH | 39.032 | 1 |

| 2. Kuchinskaya | URS | 38.865 | 2 |

| 3. Ikeda | JPN | 38.599 | 3 |

| 4. Ikenaga | JPN | 38.266 | 12 |

| 5. Zuchold | GDR | 38.265 | 4 |

| 6. Shibuya | JPN | 38.232 | 9 |

| 7. Sedláčková | TCH | 38.099 | 5 |

| 7. Latynina | URS | 38.099 | 11 |

| 9. Krajčírová | TCH | 37.999 | 7 |

| 10. Petrik | URS | 37.966 | 6 |

Because of Petrik’s mistake, she was out of the running to challenge Čáslavská, which left Kuchinskaya as the top contender.

As a result, the Soviet team organized their line-up to boost Kuchinskaya’s scores.

Kuchinskaya then took over the solo role of challenger to the all-around crown, with the entire Russian squad lining up in the optional phase of the competition to push her scores to the ultimate limit.

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1966

But it was not enough. Čáslavská, the 1964 Olympic champion, won the all-around title.

Final Standings – Top 20

| Vault | Bars | Beam | Floor | Total | |

| 1. Čáslavská | TCH | 78.298 | |||

| C. | 9.766 | 9.800 | 9.666 | 9.800 | 39.032 |

| O. | 9.733 | 9.833 | 9.800 | 9.900 | 39.266 |

| 2. Kuchinskaya | URS | 78.097 | |||

| C. | 9.633 | 9.800 | 9.666 | 9.766 | 38.865 |

| O. | 9.666 | 9.833 | 9.833 | 9.900 | 39.232 |

| 3. Ikeda | JPN | 76.997 | |||

| C. | 9.600 | 9.766 | 9.600 | 9.633 | 38.599 |

| O. | 9.433 | 9.833 | 9.466 | 9.666 | 38.398 |

| 4. Zuchold | GDR | 76.596 | |||

| C. | 9.666 | 9.500 | 9.533 | 9.566 | 38.265 |

| O. | 9.666 | 9.733 | 9.266 | 9.666 | 38.331 |

| 5. Sedláčková | TCH | 76.465 | |||

| C. | 9.500 | 9.433 | 9.566 | 9.600 | 38.099 |

| O. | 9.533 | 9.600 | 9.600 | 9.633 | 38.366 |

| 6. Petrik | URS | 76.366 | |||

| C. | 9.466 | 9.200 | 9.600 | 9.700 | 37.966 |

| O. | 9.500 | 9.600 | 9.700 | 9.600 | 38.400 |

| 7. Krajčírová | TCH | 76.332 | |||

| C. | 9.533 | 9.700 | 9.466 | 9.300 | 37.999 |

| O. | 9.600 | 9.700 | 9.500 | 9.533 | 38.333 |

| 8. Kubičková | TCH | 76.232 | |||

| C. | 9.400 | 9.600 | 9.400 | 9.533 | 37.933 |

| O. | 9.533 | 9.533 | 9.433 | 9.800 | 38.299 |

| 9. Shibuya | JPN | 76.165 | |||

| C. | 9.500 | 9.666 | 9.533 | 9.533 | 38.232 |

| O. | 9.500 | 9.800 | 9.100 | 9.533 | 37.933 |

| 10. Druzhinina | URS | 76.164 | |||

| C. | 9.366 | 9.433 | 9.366 | 9.666 | 37.831 |

| O. | 9.533 | 9.500 | 9.500 | 9.800 | 38.333 |

| 11. Latynina | URS | 76.098 | |||

| C. | 9.333 | 9.666 | 9.500 | 9.600 | 38.099 |

| O. | 9.500 | 9.500 | 9.466 | 9.533 | 37.799 |

| 12. Ikenaga | JPN | 75.999 | |||

| C. | 9.600 | 9.666 | 9.500 | 9.500 | 38.266 |

| O. | 9.500 | 9.533 | 9.200 | 9.500 | 37.733 |

| 13. Astakhova | URS | 75.997 | |||

| C. | 9.233 | 9.733 | 9.466 | 9.533 | 37.965 |

| O. | 9.333 | 9.700 | 9.533 | 9.466 | 38.032 |

| 14. Striegler | GDR | 75.930 | |||

| C. | 9.333 | 9.500 | 9.366 | 9.466 | 37.665 |

| O. | 9.566 | 9.600 | 9.366 | 9.733 | 38.265 |

| 15. Kharlova | URS | 75.896 | |||

| C. | 9.566 | 9.466 | 9.333 | 9.566 | 37.931 |

| O. | 9.500 | 9.566 | 9.433 | 9.466 | 37.965 |

| 16. Řimnáčová | TCH | 75.865 | |||

| C. | 9.433 | 9.333 | 9.400 | 9.433 | 37.599 |

| O. | 9.533 | 9.500 | 9.600 | 9.633 | 38.266 |

| 17. Mitsukuri | JPN | 75.864 | |||

| C. | 9.200 | 9.733 | 9.266 | 9.566 | 37.765 |

| O. | 9.466 | 9.700 | 9.333 | 9.600 | 38.099 |

| 18. Košťálová | TCH | 75.698 | |||

| C. | 9.366 | 9.533 | 9.433 | 9.400 | 37.732 |

| O. | 9.600 | 9.400 | 9.400 | 9.566 | 37.966 |

| 19. Tressel | HUN | 75.599 | |||

| C. | 9.300 | 9.633 | 9.400 | 9.400 | 37.733 |

| O. | 9.233 | 9.733 | 9.500 | 9.400 | 37.866 |

| 20. Furuyama | JPN | 75.598 | |||

| C. | 9.400 | 9.566 | 9.266 | 9.700 | 37.932 |

| O. | 9.400 | 9.466 | 9.200 | 9.600 | 37.666 |

And the crowd was thrilled with their victor, “Golden Věra.” Mayhem ensued.

The spectators, if circumstances had been reversed, would have easily abandoned their favorite, surged from their boxes to mob the “Golden Czech”. Only through the assistance of the police and “strong arm” ushers could the 1966 World All-Around Champion get to the safety of her dressing room.

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1966

Čáslavská was a star.

The translated quote from the “Mannheimer Morgen,” a Mannheim (city) daily newspaper. “Golden Věra”. She smiles like a film star, carries herself like a model, and ascends the award platform with the dignity of a queen … the Worid Champion Věra Čáslavská.”

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1966

Though she had just won the all-around, Čáslavská wondered if she should quit.

The first time I really thought about leaving (competitive gymnastics) was when Kuchinskaya appeared on the world championships podium — so young, so beautiful. It seemed to me I could not compete with her. But then I felt a certain impulse: I wanted to beat just such a multifaceted rival.

Qtd. in Women’s Gymnastics: A History by Minot Simons II

Event Finals

Reminder: Only six gymnasts qualified for event finals. Qualification for finals was based on the compulsory *and* optional scores on each event.

Your final score was the average of your compulsory and optional scores + the score for your routine during event finals.

Side Horse Vault

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Čáslavská | TCH | 9.750 | 9.833 | 19.583 |

| 2. Zuchold | GDR | 9.666 | 9.733 | 19.399 |

| 3. Kuchinskaya | URS | 9.650 | 9.666 | 19.316 |

| 4. Starke | GDR | 9.550 | 9.666 | 19.216 |

| 5. Krajčírová | TCH | 9.566 | 9.633 | 19.199 |

| 6. Ikenaga | JPN | 9.550 | 9.600 | 19.150 |

Uneven Parallel Bars

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Kuchinskaya | URS | 9.816 | 9.800 | 19.616 |

| 2. Ikeda | JPN | 9.800 | 9.766 | 19.566 |

| 3. Mitsukuri | JPN | 9.716 | 9.800 | 19.516 |

| 4. Čáslavská | TCH | 9.816 | 9.666 | 19.482 |

| 5. Astakhova | URS | 9.716 | 9.700 | 19.416 |

| 6. Shibuya | JPN | 9.733 | 9.600 | 19.333 |

Balance Beam

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Kuchinskaya | URS | 9.750 | 9.900 | 19.650 |

| 2. Čáslavská | TCH | 9.733 | 9.600 | 19.333 |

| 3. Petrik | URS | 9.650 | 9.600 | 19.250 |

| 4. Ikeda | JPN | 9.533 | 9.700 | 19.233 |

| 4. Ducza | HUN | 9.600 | 9.633 | 19.233 |

| 6. Sedláčková | TCH | 9.583 | 9.600 | 19.183 |

Floor Exercise

| Gymnast | Country | COA | Finals | Total |

| 1. Kuchinskaya | URS | 9.833 | 9.900 | 19.733 |

| 2. Čáslavská | TCH | 9.850 | 9.833 | 19.683 |

| 3. Druzhinina | URS | 9.733 | 9.933 | 19.666 |

| 4. Petrik | URS | 9.650 | 9.766 | 19.416 |

| 5. Kubičková | TCH | 9.663 | 9.700 | 19.363 |

| 6. Furuyama | JPN | 9.650 | 9.666 | 19.316 |

Druzhinina had the highest score of the competition: a 9.933 on floor. But it was Kuchinskaya who won three gold medals, including the floor title.

Remember the Soviet strategy? During the final rotation, they had Zinaida Druzhinina lead off the team, even though she was the best floor worker.

Well, it had consequences for Druzhinina.

But it did cost another new breed face, Zinaida Druzhinina, her deserved Gold Medal in the Floor Exercise Event. This youngster was placed early in the Floor Exercise line-up to build the team scoring. It did bring Petrik’s score up, with a 9.9 and 10 popping out of Duzhinina’s FX jury, as well as hand Kuchinskaya the Floor Exercise title.

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1966

Kuchinskaya’s three gold medals marked the end of an era and the beginning of another one.

The shift had begun already in 1964 at the Soviet Nationals, but now, it played itself out at the World Championships.

The crowning of Kuchinskaya, as the individual victor in three events, marked the end of an era … and the birth of a new decade, a new breed of performers as well as style of performance.

For nearly ten years Latynina, Astakhova, Manina, Volchetskaya were a few of the Russian names that ruled the world of women’s gymnastics. At Dortmund only Astakhova and Latynina remained, both leaders in the Japan Olympics but now, just two years later in Germany, the victims of time and progress. Known as the “pace setters” of artistic movement, in terms of difficulty, performance and style, vacated the “Dias” for the new young breed of “kids”. Kids, who perhaps only yesterday, had cherished the ground upon which they walked. Astakhova and Latynina “stepped down” with the graciousness and dignity of the champions they were … but only they alone know the feeling … the hurt, the disappointment … of the champion who knows they no longer have what it takes to meet the challenge of youth.

Modern Gymnast, Dec. 1966

On floor, the female gymnasts performed as much difficulty as their male counterparts.

The acrobatic difficulties are equal to those of the men. Kuchinskaya and Druzhinina perform a back somersault with a full twist, another with a half twist, and a straight back somersault with anterior-posterior split of the lower limbs. Some perform a front handspring followed by a front salto. Most of their acrobatic difficulties are graded “C” for men. The technique is perfect, only the height is a little less.

EP&S, Nov. 1966

Les difficultés acrobatiques sont égales à celles des hommes. Koutschinskaia et Drouginina réalisent dans leur mouvement un salto arrière avec vrille complète, un autre avec une demi-vrille et un salto arrière tendu avec écart antéro-postérieur des membres inférieurs. Certaines réalisent le saut de mains suivi d’un salto avant. La plupart de leurs difficultés acrobatiques sont classés « C » chez les hommes. La technique en est parfaite, seule l’élévation est un peu moindre.

Judging Controversy

“Das War Betrug!” (“It was a fraud!”)

That’s what the German newspapers reported. U.S. gymnast Doris Brause received a 9.766 for her uneven bars routine, and the crowd was not pleased.

Irate whistles and stomping stopped the meet for one hour and three minutes. But to no avail. The judges didn’t raise her score.

It was the first time that a gymnast had “swung bars.” In the next post, we’ll take a look at what that meant and why this routine was pivotal in women’s gymnastics history.

Here’s a little preview:

The judging can also be criticized; some judges are incapable, others are biased. To avoid partiality, jurors from small nations (on the gymnastics level) are used, but countries that do not have good gymnasts rarely have great judges, if only because of their lack of practice. It is regrettable to see incidents like the one suffered by the young American on uneven bars. Furthermore, the judges should no longer be influenced by the name of the gymnast, but by his or her performance. The only solution, all the exercises recorded on the video recorder and in case of discussion, the film would be replayed. The disadvantage, the judgment on film is much more severe.

EP&S, Nov. 1966, emphasis my own

Critiquable aussi le jugement ; certains juges sont incapables, d’autres sont partiaux. Pour éviter la partialité on contacte des jurés de petites nations (sur le plan gymnique), mais les pays qui n’ont pas de gymnastes de valeur ont rarement de grands juges ne serait-ce que par leur manque de pratique. Il est regrettable de voir des incidents comme celui dont a été victime la jeune Américaine aux asymétriques. En outre, les juges ne doivent plus être influencés par le nom du gymnaste, mais par sa prestation. La seule solution, tous les exercices enregistrés au magnétoscope et en cas de discussion, le film serait repassé. L’inconvénient, le jugement sur film est beaucoup plus sévère.