Female gymnasts did not compete in the International Tournament or in the Belgian Federal Festival. But they did perform, and according to the newspaper reports, they were crowd favorites.

In this article, we’ll take a look at those newspaper reports, as well as some of the challenges facing women’s gymnastics in fin-de-siècle western European society.

Note: I’m going to refer to it as “women’s gymnastics” in this post, but we won’t be discussing the performances of adult women. Rather, the gymnasts were typically young girls.

Reminder

The first World Championships were held in Antwerp. However, they weren’t called World Championships at the time. They were referred to as the International Tournament (Tournoi International de Gymnastique in French or Internationale Turntornooi in Dutch).

The competition was held in conjunction with the Belgian Federal Festival, August 14-18, 1903, and was organized by the Bureau des Fédérations Européennes de Gymnastique (Bureau of European Gymnastics Federations), which was the former name of the FIG.

For more on the 1903 International Tournament, head over to this post.

With that caveat out of the way, let’s jump into the performances…

The Belgians

On Monday, August 17, 1903, before the awards ceremony for the International Tournament, there was a series of demonstrations, which included a group of Belgian young women, who performed with portable hand apparatus (similar to rhythmic gymnastics nowadays), as well as on the competitive apparatus.

The program was particularly interesting: first of all, we saw working about sixty young girls, members of the sections, ladies of the “Turn- en Wapenclub” of Antwerp-South, of the “Liersche Turnkring” and of the Gymnastics Circle of Boom. And there were charming group movements with canes, hoops, and clubs, beautiful mobility exercises on the apparatus. Then came the boys of the “Volkskring”, working on the bars as accomplished gymnasts.

Le programme était particulièrement intéressant: tout d’abord, on vit travailler une soixantaine de jeunes filles, membres des sections, de dames du “Turn- en Wapenclub” d’Anvers-Sud, du “Liersche Turnkring” et du Cercle gymnastique de Boom. Et ce furent de charmants mouvements d’ensemble avec cannes, cerceaux et massues, des exercices d’une belle correction aux engins. Puis vinrent les garçonnets du “Volkskring”, travaillant aux barres en gymnastes accomplis.

Le Matin, August 18, 1903

The Dutch were shocked by some of the exercises performed by the Belgian group.

Letting children of barely ten years of age perform a straddle stance outside the handles of the horse and alternately raising one leg out of support, we considered wrong on good grounds.

Kinderen van nauwelijks tien jaar oen spreidstand buiten de beugels van het paard te laten uitvoeren en uit steun beurtelings verheffen van een been achtten wij op goede gronden verkeerd.

Algemeen Handelsblad, August 19, 1903

Note: The belief that female gymnasts shouldn’t perform straddle positions was fairly pervasive at the time. Podesta, one of the most vocal proponents of women’s gymnastics in France, wrote in 1909:

As for apparatus, stick to parallel bars, avoiding any straddle exercise, or any acrobatic exercise […]

Comme agrès, il faut s’en tenir aux barres parallèles, en évitant tout exercice au siège écarté, ou tout exercice acrobatique […]

La culture physique, May 1, 1909

You can read the full letter below.

The Danes

While the audience admired the Belgian gymnasts, the Danish young women were the ones who stole the show. They, too, performed Monday before the awards ceremony for the International Tournament.

But the big success were the Italian gymnasts and the Danish ladies.

Mais le gros succès devait aller aux gymnastes italiens et aux dames danoises.

Le Matin, August 18, 1903

They worked across a variety of apparatus using a variety of styles.

The young Danish ladies worked for more than an hour and literally amazed the audience. What they do is basically like our ordinary gymnastics, but presented in a strangely charming way. One is a little disconcerted to see them bend their bodies and raise their arms with the graces of ancient dance, then suddenly march and turn with the stiffness of soldiers, do pointe work like a ballerina, then execute flight skills on the bars, slide on a narrow beam with feline suppleness and sculptural poses, then embark on a sort of steeplechase with enormous leaps. All this surprises a little at first, but quickly wins one over, and when the Danes ended with a march, singing the French words of the “Brabançonne,” the public burst into enthusiastic ovations, which were renewed when superb bouquets of flowers were offered to these ladies.

Les jeunes Danoises, elles, ont travaillé plus d’une heure et ont littéralement émerveillé le public. Ce qu’elles font, ressemble, au fond, à notre gymnastique ordinaire, mais cela est présenté d’une façon étrangement charmante. On est un peu déconcerté en les voyant fléchir le corps et lever les bras avec des grâces de danse antique, puis brusquement marcher et tourner avec une raideur de soldats, faire des points comme une ballerine, puis exécuter la volée aux barres, glisser sur une étroite poutre avec une souplesse féline et des attitudes sculpturales, puis se lancer en une sorte de steeple-chase aux bonds énormes. Tout cela étonne un peu tout d’abord, mais conquiert très vite, et lors que les Danoises terminèrent par une marche, en chantant les paroles françaises de la “Brabançonne”, le public éclata en enthousiastes ovations, qui se renouvelèrent lorsque de superbes gerbes de fleurs furent offertes à ces dames.

Le Matin, August 18, 1903

Note #1: The Brabançonne is the national anthem of Belgium.

From the Brabançonne at the Belgian Federal Festival in 1903 to Dvořák at the 1962 World Championships in Prague to “Big in Japan” at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, there’s a long history of trying to appeal to the host nation through music.

Note #2: Can you imagine if all gymnasts had to sing as they performed nowadays?

In addition to the exhibition of the Danish gymnasts before the awards ceremony on Monday, they performed on Sunday night as part of the “poses plastiques” portion of the Federal Festival. These performances were sometimes called “tableaux vivants” (“living pictures”) and were part of the French federal festivals, as well. The gymnasts all dressed in white so that they would look like statues. Here, too, the Danish women were extremely popular.

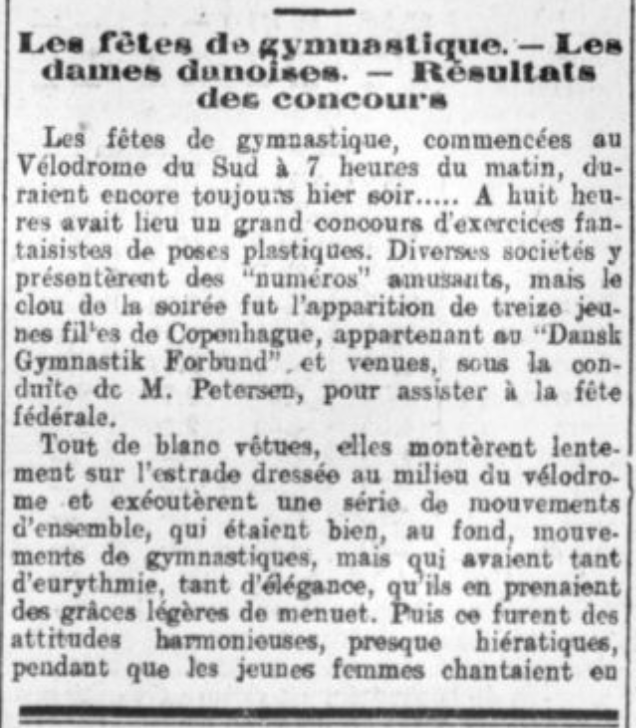

The gymnastics festivals, which began at the Vélodrome du Sud at 7 a.m., were still going on yesterday evening… At eight o’clock a big exercise competition took place in fanciful artistic poses. Various societies presented amusing “acts” there, but the highlight of the evening was the appearance of thirteen young girls from Copenhagen, belonging to the “Dansk Gymnastik Forbund,” who came, led by Mr. Petersen, to attend the federal festival.

Dressed all in white, they slowly ascended the platform erected in the middle of the velodrome and performed a series of ensemble movements, which were indeed, basically, gymnastic movements, but which had so much eurythmy, so much elegance, that they took on the light graces of a minuet. Then there were harmonious, almost hieratic poses, while the young women quietly sang a very dancey and serious song, with a penetrating charm… Finally, with a feeling of pretty delicacy, the Danish women performed a march while singing, in French, the “Brabançonne.”

Les fêtes de gymnastique, commencées au Vélodrome du Sud à 7 heures du matin, duraient encore toujours hier soir… A huit heures avait lieu un grand concours d’exercices fantaisistes de poses plastiques. Diverses sociétés y présentèrent des “numéros” amusants, mais le clou de la soirée fut l’apparition de treize jeunes filles de Copenhague, appartenant au “Dansk Gymnastik Forbund” et venues, sous la conduite de M. Petersen, pour assister à la fête fédérale.

Tout de blanc vêtues, elles montèrent lentement sur l’estrade dressée au milieu du vélodrome et exécutèrent une série de mouvements d’ensemble, qui étaient bien, au fond, mouvements de gymnastiques, mais qui avaient tant d’eurythmie, tant d’élégance, qu’ils en prenaient des grâces légères de menuet. Puis ce furent des attitudes harmonieuses, presque hiératiques, pendant que les jeunes femmes chantaient en sourdine un chant très danse et très grave, d’un charme pénétrant… Enfin, par une sentiment de jolie délicatesse, les danoises exécutèrent une marche en chantant, en français, la “Brabançonne.”

Le Matin, August 18, 1903

The Obstacles to Competition

While young girls performed at the 1903 Belgian Federal Festival, they didn’t compete. Women wouldn’t compete at the Olympics in gymnastics until 1928, and they wouldn’t compete at the World Championships until 1934.

Female gymnasts had to overcome several obstacles that men did not. To give you an idea of how women’s gymnastics was perceived in the early 1900s, let’s take a look at a few passages.

⁂ ⁂ ⁂

In Germany, one of the biggest obstacles was the notion that women should not be seen exercising in public. Here’s what Annette R. Hofmann writes in the book Turnen and Sport:

The discussion about “women’s issues” in the DT [the German Gymnastics Federation] did not only focus on membership rights but also on the public appearance of female Turners.

From the beginning, gymnastic performances had a variety of goals: they wanted to present exercises and performances, give the audience stimuli and advertise for women’s gymnastics. Public performances of girls’ and women’s gymnastics were generally controversial because decent women did not appear in public. For this reason some turner halls had curtains in front of their windows in order that no one could look through them while women were doing their exercises.

In 1894, 50 female Turners of a Verein from Breslau dared to perform at the VIII. Deutsche Turnfest in Breslau. Four years later there were already 1,000 lady turners from Hamburg who performed difficult and improper exercises on apparatus at the IX. Turnfest in their home city. Until World War I, the question of whether and how women should participate at German Turnfests provoked fierce discussions within the turner movement, generated by a concern for morality and the fear of an emancipation which would destory German family life and German Volkstum.

Concerns about gymnastics’ impact on family life weren’t just a German phenomenon. Similar ideas were circulating in Italy (by way of France). In 1905, the Italian federation’s Il Ginnasta printed a letter from Albert Herrenschmidt, the editor of the French periodical Petit Havre. After discussing the number of female gymnasts in various European countries, his letter concluded by highlighting some of the benefits of female sport (“lo sport femminile”), whose practice

distracts the spirit, it reconstitutes the muscles, develops a sense of initiative, a cool head, decision-making, in a word, it procures all the hygienic advantages of physical exercise taking into account the family and social role that the girl who has become a woman will one day be called upon to support.

distrae lo spirito, ricostituisce i muscoli, sviluppa il senso dell’iniziativa, il sangue freddo, la decisione, procura in una parola tutti i vantaggi igienici dell’esercizio fisico tenendo conto della parte famigliare e sociale che la ragazza divenuta donna, sarà un giorno chiamata a sostenere.

Il Ginnasta, April 1, 1907

Note: The article specifically uses the English term “sport.” At the time, “sport” referred to the British model of competitive sports among the upper classes and social elite. For more, see, for example, Vanessa Heggie’s “Bodies, Sport, and Science in the Nineteenth Century.”

The letter flipped the script ever so slightly by positioning sports for girls as congruent with family life rather than antagonistic to it. Sports, according to this view, prepared young girls to become wives and mothers because they taught them the skills necessary for such roles.

The view that gymnastics was good for young girls — not necessarily for adult women — was also circulating in France at the time. In a letter printed in Le culture physique, E. Podesta, a staunch supporter of female gymnastics in France, suggested that competitive gymnastics teams were acceptable for prepubescent girls, but once they hit the age of fourteen or fifteen, they should stop.

At the present time and for quite a long time to come, to avoid presenting young girls in public, have only little girls aged eight years minimum and fourteen to fifteen years maximum, and even at this last age, they should be neither too large nor too developed.

A l’heure et pendant encore un assez long temps, éviter de présenter en public des jeunes filles, n’avoir que des fillettes de huit ans minimum et de quartorze à quinze ans maximum et encore dans ce dernier âge, qu’elles ne soient ni trop grandes ni trop développées.

La culture physique, May 1, 1909

Interestingly enough, both the Belgian and Danish performers at the Belgian Federal Festival (discussed above) were referred to as young ladies or girls. The articles made it clear that they weren’t adult women. (When female gymnasts first performed at the French Federal Festival in 1882, they, too, were young girls.)

This is an important reminder that the question of age in women’s gymnastics has been a pendulum. While proponents like Podesta supported gymnastics for prepubescent girls in the early 1900s, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction by the middle of the century. The rules for the 1952 Olympics, for example, required that all female gymnasts be over the age of 18. They could be 16 if they had a medical certificate:

The gymnasts must be 18 years old during the year of the competition, be of the nationality of the Federation which delegates them and be part of a federated society. However, a lady-gymnast, having reached the age of 16, will be authorized to compete, provided that she presents a medical certificate indicating that she is physically capable of withstanding the tests imposed in the competition without danger. No gymnast under the age of 16 will be allowed to compete.

Les gymnastes devront avoir 18 ans révolus au cours de l’année du concours, être de la nationalité de la Fédération qui les délègue et faire partie d’une société fédérée. Toute-fois, une gymnaste-dame, ayant 16 ans révolus, sera autorisée à concourir, à condition de présenter un certificat médical indiquant qu’elle est physiquement capable de supporter sans danger les épreuves imposées au concours. Aucune gymnaste en dessous de 16 ans ne sera admise à concourir.

Programme et règlement, Gymnastique, 1952

In addition to the question of age, E. Podesta outlined many of the concerns that women’s gymnastics coaches faced in French society. (He was seen as an expert in the subject since he started the first women’s team in a French gymnastics society in 1900.) Those included how to dress female bodies in public, being the stars of festivals and competitions, the lack of equal prize money, and more.

Here’s a translation of Podesta’s letter.

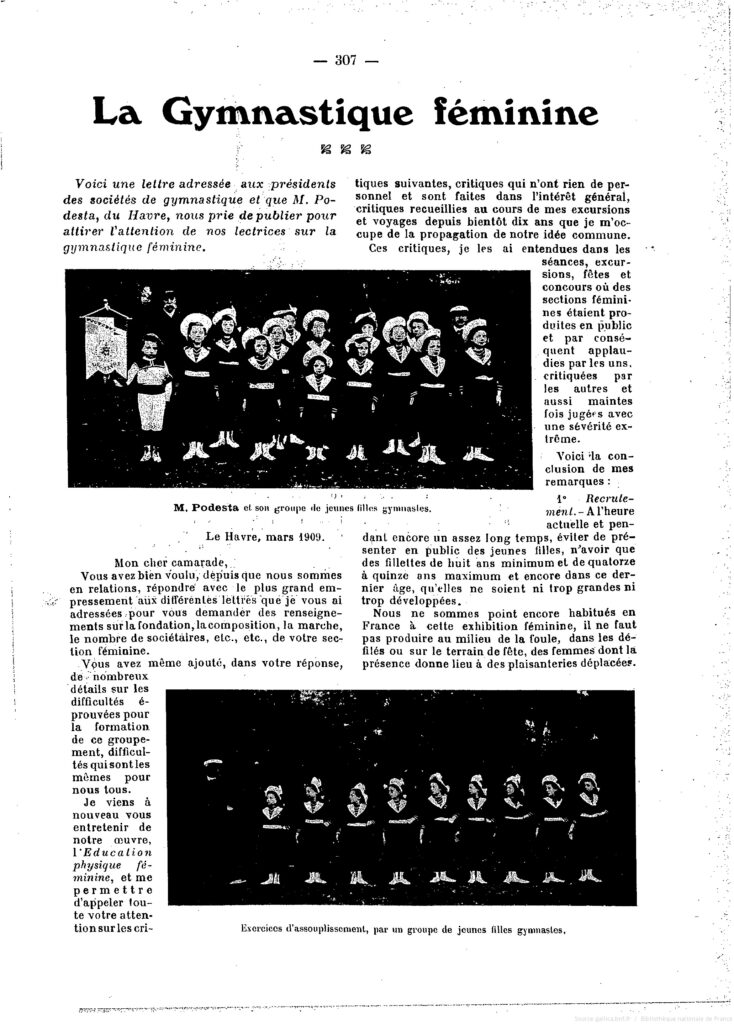

Here is a letter addressed to the presidents of gymnastic societies and which Mr. Podesta, from Le Havre, asks us to publish to draw the attention of our readers to women’s gymnastics.

You were kind enough, since we have been in contact, to respond with the greatest eagerness to the various letters I have sent to you asking for information on the foundation, the composition, the operation, the number of members, etc., etc. ., of your women’s team.

You even added, in your answer, numerous details on the difficulties experienced in the formation of this group, difficulties which are the same for all of us.

I come once again to talk to you about our work, Women’s Physical Education, and allow myself to draw your full attention to the following criticisms, criticisms which have nothing personal and are made in the general interest, criticisms collected during my excursions and travels for nearly ten years that I have been involved in the propagation of our common idea.

These criticisms, I heard them in the meetings, excursions, festivals and competitions where female sections were produced in public and consequently applauded by some, criticized by others and also repeatedly judged with extreme severity.

Here is the conclusion of my remarks:

1st Recruitment — At the present time and for quite a long time to come, to avoid presenting young girls in public, have only little girls aged eight years minimum and fourteen to fifteen years maximum, and even at this last age, they should be neither too large nor too developed.

We are not yet accustomed in France to this feminine exhibition, we must not produce in the middle of the crowd, in parades or on the party ground, women whose presence gives rise to inappropriate jokes.

2nd Dress — Here again great care must be taken, the outfit must be pretty, very feminine although practical, at no price should we allow the outfit with knickers (culotte)* without a skirt, that we remember well the harm done to the female velocipede the exhibition of women in knickers on bicycles, save this outfit for lessons in the gymnasium where the public must never be admitted.

The most suitable costume is: cycle bloomers, reaching below the knee, puffy bodice with wide sleeve stopping below the elbow, gathered or pleated skirt not exceeding above the knee so that the movements of the legs are free.

For the hairstyle, avoid the cap or the English jockey, the cap is particularly unsightly and why do we style our girls as boys? The police cap itself is subject to criticism; If a small eight-year-old girl is charming with this hairstyle, what unflattering casualness it gives to a fourteen-year-old girl, already tall!

The beret is the hairstyle that gets the most votes; it is bold, it’s true, but always coquettish, even if it poses too audaciously, because its form lends itself to the conformation of the head and the face.

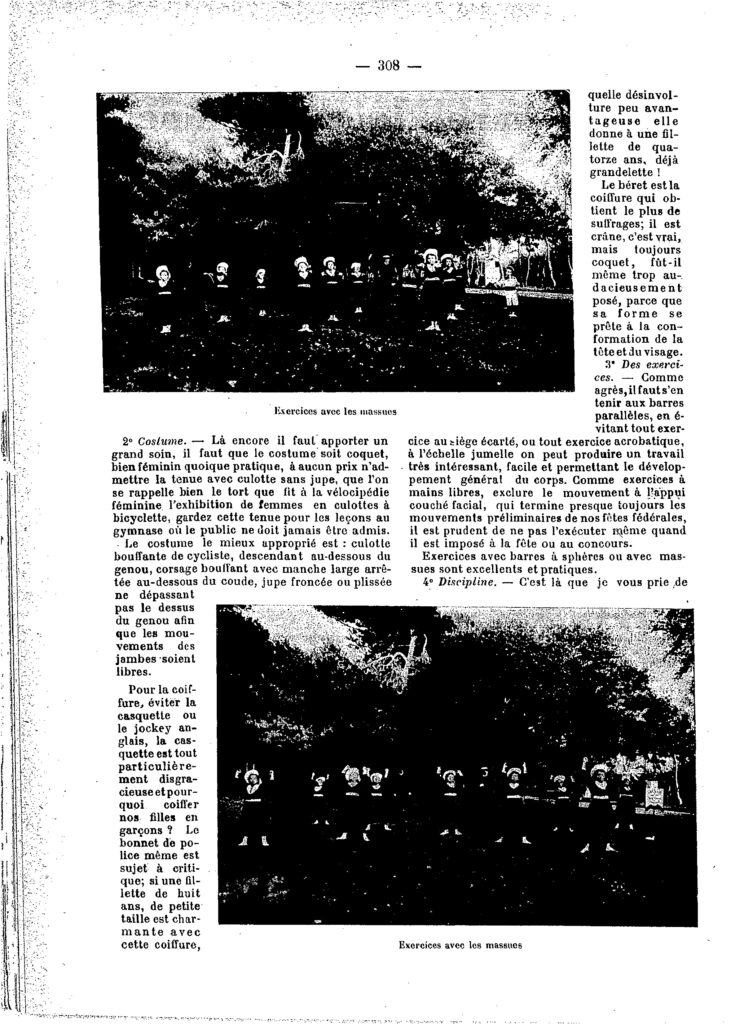

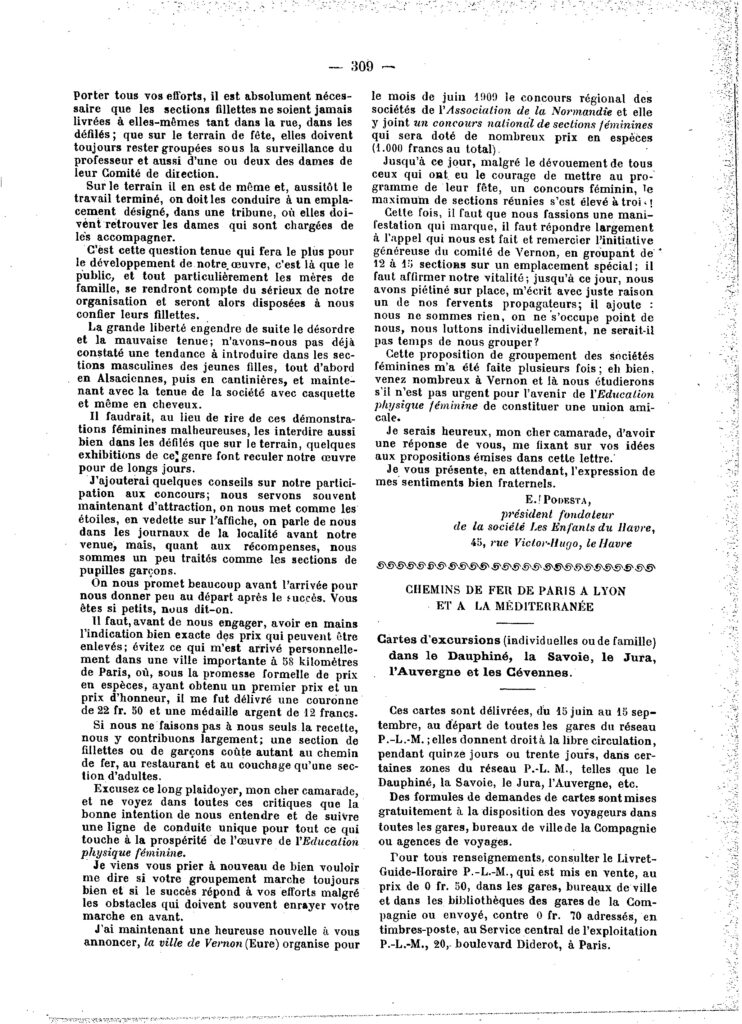

3rd Exercises — As apparatus, stick to parallel bars, avoiding any straddle exercise, or any acrobatic exercise, or twin ladders can produce very interesting work, easy and allowing the general development of the body. As for floor exercise, exclude the movement to the facial lying support, which almost always completes the preliminary movements of our federal festivals, it is prudent not to perform it even when it is imposed on the festival or the competition.

Exercises with sphere bars or with clubs are excellent and practical.

4th Discipline — This is where I beg you to put all your efforts, it is absolutely necessary that the girls’ sections are never left to themselves so much in the street, in the parades; that on the festival ground, they must always remain grouped under the supervision of the teacher and also of one or two of the ladies of their Management Committee.

On the ground it is the same and, as soon as the work is finished, they must be taken to a designated place, in a gallery, where they must meet the ladies who are responsible for accompanying them.

It is this question that will do the most for the development of our work, it is there that the public, and especially the mothers, will realize the seriousness of our organization and will then be willing to entrust their little girls to us.

Great freedom immediately engenders disorder and poor behavior; have we not already noticed a tendency to introduce into the male sections of young girls, first in the women of Alsace, then in lunch ladies, and now with the dress of society with cap and even in hair.

It would be necessary, instead of laughing at these unfortunate feminine demonstrations, to prohibit them as well in the parades as on the ground; exhibitions of this kind set back our work for a long time.

I will add some advice on our participation in competitions; we are often now used as an attraction, we are put like stars, featured on the poster, we are talked about in the local newspapers before we come, but, when it comes to rewards, we are treated a little like the sections of boys’ pupils.

We are promised a lot before the finish to give us little at the departure after the success. You are so small, we are told.

It is necessary, before committing ourselves, to have in hand the very exact indication of the prizes, avoid what happened to me personally in an important city 58 kilometers from Paris, where, under the formal promise of prizes in cash, having obtained a first prize and a prize of honor, I was issued a crown of 22 fr. 50 and a silver medal of 12 francs.

If we do not make the revenue ourselves, we contribute greatly to it; a section of girls or boys costs as much for the railway, the restaurant and the sleeping quarters as an adult section.

Excuse this long plea, my dear comrade, and see in all these criticisms only the good intention of agreeing and following a single line of conduct for all that touches the prosperity of the work of Women’s Physical Education.

I come to ask you once again to kindly tell me if your group is still going well and if success responds to your efforts despite the obstacles that often have to stop your progress.

I now have happy news to announce to you, the town of Vernon (Eure) is organizing for the month of June 1909 the regional competition for the societies of the Association of Normandy and it is joining a national competition for women’s sections which will be endowed with numerous cash prizes (1,000 francs in total).

To date, despite the dedication of all those who have had the courage to put a women’s competition on the program of their party, the maximum of sections gathered has risen to three!

This time, we must have a demonstration where we leave our mark, we must respond broadly to the call made to us and thank the generous initiative of the Vernon committee, by grouping 12 to 15 sections on a special site; we must affirm our vitality; up to this day, we trampled in place, one of our fervent propagators writes me with good reason; he adds: we are nothing, no one takes care of us, we fight individually, wouldn’t it be time to group us?

This proposal for a group of women’s societies has been made to me several times; well, come many to Vernon and there we will study if it is not urgent for the future of female physical education to constitute a friendly union.

I would be happy, my dear comrade, to have an answer from you, focusing on your ideas for the proposals made in this letter.

I present to you, in the meantime, the expression of my very fraternal sentiments.

E.Podesta

La culture physique, May 1, 1909

Founding President

of the society Les Enfants du Havre

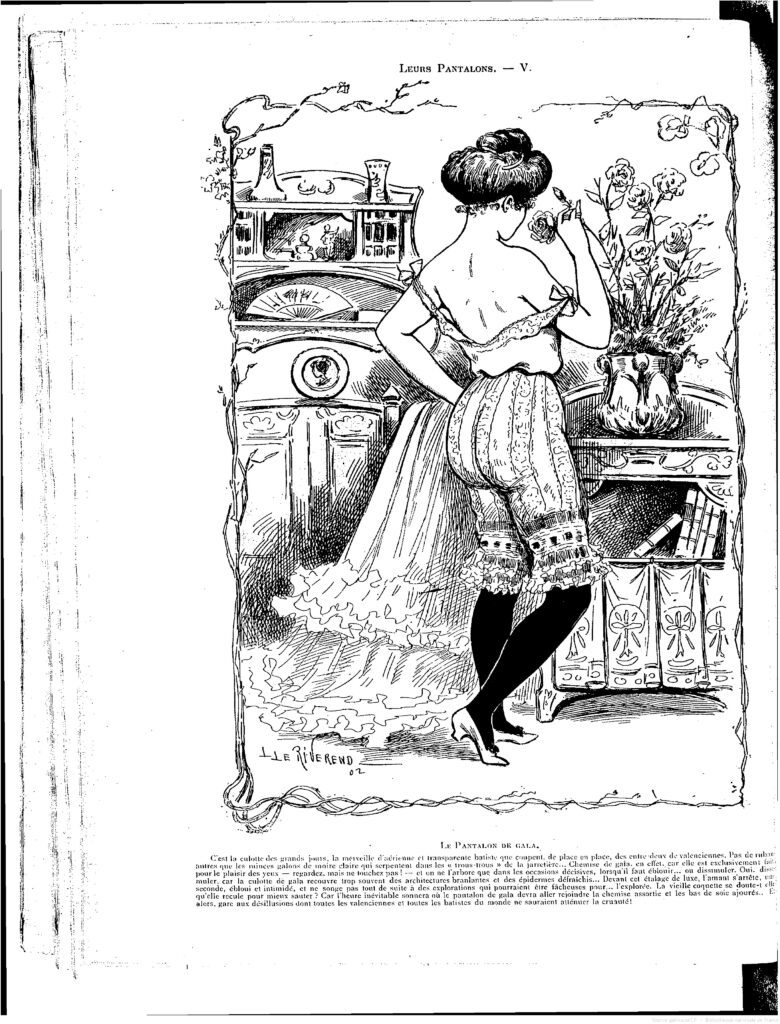

*If you’re not an expert in fin-de-siècle clothing and are having trouble picturing the knickers discussed above, here’s an image of a culotte from the magazine Le Frou-Frou in January of 1903.

The French original of the letter — with photos of the gymnasts.

By the way, when female gymnasts first performed at the French Federal Festival in 1882, they were young girls, as well. They weren’t part of a gymnastics club or society. Rather, they were part of the secular schools in the city of Reims.

We can say, and without offending the feelings of our fellow gymnasts, that the group movements by the students of the girls’ schools in the city of Reims were the highlight of this first day. Not that the exercises were particularly important. The movements were very simple; they were punctuated by a rhythmic song, and we can add, they were very well executed, with admirable enthusiasm, commanded with a quite maternal firmness by Miss Boucton, gymnastics instructor of the secular schools for girls in the city of Reims. But what for us is an event is that we have dared, contrary to the bitter criticisms of a certain press, to have women’s gymnastic exercises performed before the youth of our societies. Yes, this is the event of the day, and it is important. This is the first time in 22 years that we have been attending festivals of this kind that we see young girls taking an active part in a federal festival!

The effect produced by the exercises of these 200 young girls was immense… These exercises aroused the enthusiastic applause of the public and the gymnasts who, by repeated rounds of applause, underlined on several occasions the good execution of the movements, thus testifying to their real satisfaction for this new show for most of them.

Nous pouvons bien dire, et sans froisser les sentiments de nos camarades gymnastes, que les mouvements d’ensemble par les élèves des écoles de filles de la ville de Reims ont été le bouquet de cette première journée. Non pas que les exercices aient eu un caractère particulièrement important. Les mouvements étaient fort simples; ils étaient cadencés par un chant rythmé, et nous pouvons ajouter, ils ont été fort bien exécutés, avec un entrain admirable, commandés avec une fermeté toute maternelle par Mlle Boucton, monitrice de gymnastique des écoles laïques de filles de la ville de Reims. Mais ce qui pour nous est un évènement, c’est que l’on ait osé, contrairement aux critiques amères d’une certaine presse, faire manoeuvrer devant la jeunesse de nos sociétés des exercices de gymnastique féminins. Oui là est l’évènement de la journée, et il est important. C’est pour la première fois, depuis 22 ans que nous assistons à des fêtes de ce genre, que nous voyons des jeunes filles prendre une part active dans une fête fédérale!

L’effet produit par les exercices de ces 200 jeunes filles a été immense… Ces exercices ont soulevé les bravos enthousiastes du public et des gymnastes qui, par des bans répétés, soulignaient à plusieurs reprises la bonne exécution des mouvements, témoignant ainsi de leur réelle satisfaction pour ce spectacle nouveau pour la plupart d’entre eux.

Le Drapeau, June 8, 1882, Joseph Sansboeuf

Note: Sansboeuf was one of the founders of Union des sociétés de gymnastique de France