If you were going to remove one event from the men’s program, which would it be?

In 1969, vault in men’s artistic gymnastics was a major sticking point. Gymnasts were performing the same vault over and over, and some thought that the hand zones were pointless. At an FIG coaches’ meeting, some even thought that the apparatus should be eliminated.

Let’s dive into the concerns…

Problem #1: Hand Zones

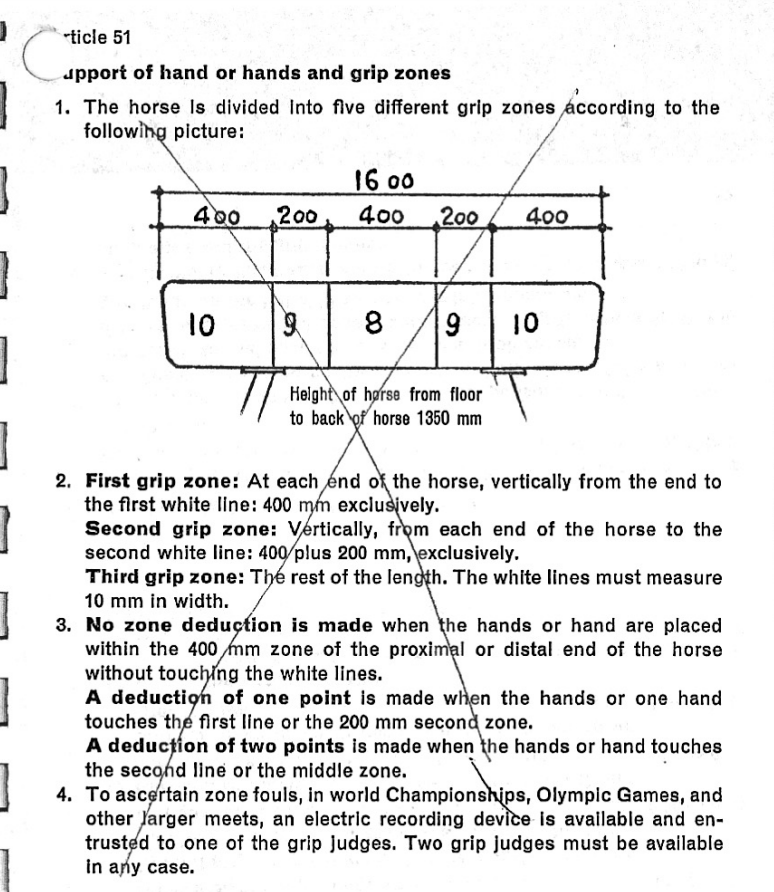

In 1969, there were five hand zones, and gymnasts had to place their hands in specific zones. Depending on the zone, the value of the vault could change.

The core vault judges were not responsible for noticing the hand placements. Rather, a machine, as well as a set of hand placement judges, were responsible for that task.

Many thought that using grip zones was an antiquated way of doing things, and it encouraged gymnasts to choose easier vaults. Here’s what was written in Olympische Turnkunst (December 1969).

Thoughts on Vault

For several years, FIG experts have been criticizing that the performance on vault, compared to that of other apparatus, has not kept pace with the development of artistic gymnastics.

The fact that the long horse’s zones are a decisive factor cannot be denied, and the question arises as to what sense and purpose such grip zones actually represent. It could be said in favor of this that only the gymnast who masters the relationship between the board and the grip on the horse correctly and who completes a vault technically correctly in this connection is the better one. – However, this argument is contradicted by the fact that the judge cannot primarily pay any attention to the grip zone, and consequently judges a vault only from a technical point of view (a grip error is subsequently taken into account in the evaluation). How fairly is the gymnast treated on this point?

All subjective judging factors of a vault are provided with an error margin of tenths of a point (e.g.: bent arms – 0.1 to 1.0 point) which is available to the judge in his evaluation. On the other hand, there is the only objectively detectable error, the grip zone, which does not allow the judge any discretion, even if with the smallest misstep.

There is no denying that the grip zone is an additional burden for the gymnast. From the starting point of the vault, i.e. from about twenty meters, the gymnast does not yet see where he has to touch (in contrast to the female gymnasts). The resulting psychological insecurity undoubtedly affects the approach and the quality of the vault. This uncertainty can only be partially compensated for by, for example, choosing a ten-point vault of the lower difficulty level such as a hecht, a handspring, etc.

Vaults of the higher level of difficulty, such as those with a 1/1 turn, require not only the inevitably higher concentration but also a start-up momentum that is intended to guarantee the correct success of the vault. A length of 400 mm as a touch area must then inevitably be regarded as too narrow. Consequently, in many cases the gymnast does not like to take that risk and prefers the “easier” ten-point vault.

Eliminating the grip zones would mean that the vaults would have to be reclassified in the Code of Points, but this should not have any influence on the technical assessment of a vault.

This would be one of the ways to encourage gymnasts and give them the opportunity to contribute to the development of vault.

Gedanken zum Pferdsprung

Christian Webor-Ames (USA)

In Fachkreisen des ITB wird schon seit mehreren Jahren kritisiert, daß die Leistungen des Pferdspringens, verglichen mit denen der anderen Geräte, nicht mit der Entwicklung des Kunstturnens schrittgehalten haben.

Daß die Griffzonen des Langpferdes dabei einen entscheidenden Faktor darstellen, ist sicher nicht von der Hand zu weisen, und es stellt sich die Frage, welchen Sinn und Zweck solche Griffzonen eigentlich darstellen. Befürwortend ließe sich dazu sagen, daß eben nur der Turner, der das Verhältnis zwischen Brett und Aufgriff auf das Pferd richtig meistert und in diesem Zusammenhang einen Sprung technisch korrekt absolviert, der bessere ist. – Diesem Argument widerspricht jedoch die Tatsache, daß der Kampfrichter primär keinerlei Beachtung der Griffzone widmen kann, folglich also einen Sprung nur nach technischen Gesichtspunkten beurteilt (ein Griffehler wird nachträglich in der Bewertung berücksichtigt). Wie gerecht wird der Turner in diesem Punkt behandelt?

Alle subjektiven Beurteilungsfaktoren eines Sprungs sind mit einer Fehlerbreite von Zehntelpunkten versehen (z. B.: gebeugte Arme – 0,1 bis 1,0 Punkte), die dem Kampfrichter bei seiner Bewertung zur Verfügung stehen. Dagegen steht der einzige, objektiv feststellbare Fehler, die Griffzone, die dem Kampfrichter keinen Ermessensraum gestattet, selbst bei einem noch so geringfügigen Danebengreifen.

Daß die Griffzone für den Turner eine zusätzliche Belastung bedeutet, ist nicht zu bestreiten. Vom Ausgangspunkt des Sprunges, also aus etwa zwanzig Metern, sieht der Turner noch nicht, wo er aufzugreifen hat (im Gegensatz dazu die Turnerinnen). Die daraus resultierende psychologische Unsicherheit beeinflußt zweifellos den Anlauf und die Qualität des Sprunges. Diese Unsicherheit kann nur teilweise kompensiert werden, wie etwa durch die Wahl eines Zehn-Punkte-Sprunges der unteren Schwierigkeitsstufe wie Hecht, Überschlag etc.

Sprünge der oberen Schwierigkeitsstufe wie etwa solche mit 1/1 Drehung erfordern neben der zwangsläufig höheren Konzertration auch eine Anlaufdynamik, die das richtige Gelingen des Sprunges garantieren soll. Ein Spielraum von 400 mm als Aufgriffsbereich muß dann zwangsläufig als zu knapp angesehen werden. Folglich mag der Turner in vielen Fällen dieses Risiko nicht eingehen und bevorzugt den “leichteren” Zehn-Punkte-Sprung.

Eine Beseitigung der Griffzonen würde mit einer zwangsläufigen Neueinordnung der Sprünge im Code de Pointage verbunden sein, dürfte aber auf die technische Beurteilung eines Sprunges keinen Einfluß haben.

Diese wäre einer der Wege, die Turner zu ermutigen und ihnen die Gelegenheit zu geben, an der Entwicklung des Pferdsprunges mit beizutragen.

Problem #2: Repetitive. Should we abandon the event altogether?

In March of 1969, there was a conference for men’s coaches. During that conference, coaches reflected on the 1968 Olympics and how boring the vaults were at the competition. In fact, the IOC was not pleased with men’s vault in Mexico City.

At the time, the Code of Points rewarded gymnasts for risk, originality, and virtuosity (ROV). However, ROV was not applicable to vault. Here’s what was recorded in the pages of Modern Gymnast:

SCHUHWERE: (Junior national coach from Switzerland): “Concerning the long horse event. We must either re-evaluate this event or eliminate it.· Why does ROV not count in long horse?”

GUNTHARD (Swiss National Coach): (He was really concerned about the long horse and held the floor for some time discussing it.) “What is wrong with us? A gymnast cannot even reach 9.5 on a stoop vault? It seems that 9.35 is the best that was reached in Mexico. Are we losing sight of what gymnastics is in relation to other events? We should give thought to dropping the event.”

His reasons were:

1. Eliminate a single action on one piece of apparatus.

2. There are 11 elements on other pieces.

3. The judges have to move too quickly in order to judge properly.

4. It offers too few variations. (Not according to the Japanese.)

5. It will shorten dual meets.

GANDER [President of the FIG] TO GUNTHARD: “Yes, we must to something about long horse or cancel it. There is a lack of training in this event. It is the last item on the training program and the judges are not well trained for it. Perhaps we can solve it by using electronics. We still lack in basics here and new gymnasts can develop and learn by using a Reuther board for this event and other events.”

DOT (France): ” Perhaps the Reuther board needs adjustment for different weight gymnasts.”

Modern Gymnast, June/July 1969

Later on, Gander, the President of the FIG, would return to the subject, noting that people were bored during vault at the 1968 Olympics:

Gander followed Ivancevic by stating that long horse must look for new tactics and be made more attractive to all. “No one wants to sit through the same exercise over and over again. People were squirming in their seats.”

Modern Gymnast, June/July 1969

My Thought Bubble: It’s interesting that the Japanese delegation didn’t concur with everyone else. Perhaps they knew what was coming. One year later, at the 1970 World Championships, Tsukahara would debut his namesake on vault, and men’s vault would never be the same again.

Appendix: More Tidbits from the FIG Coaches’ Meeting

Note: If quotation marks are used, it is a quotation as printed in the article. Where there aren’t quotation marks, the author seems to be paraphrasing or summarizing points. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes are from Modern Gymnast, June/July 1969.

Gander (the President of the FIG at the time): Men’s and women’s gymnastics must remain separate. Men should not be too feminine.

He stressed that women seem to lure the men in a similar style of gymnastics but men must be careful of going too far with the feminine trend because :

1. Men’s rule have different technical view.

2. The code of points for men support masculine movements.

3. Men’s apparatus not constructed for women.

4. No real comparison to code of points and style of gymnastics.

5. Men must continue in their own personal style and not copy women who support a feminine approach to the sport.

Gander: Parallel bar routines need improvement.

”In addition to judging, the parallel bar event is still lacking in imagination but the horizontal bar is correct and past monotony.”

Gander: Avoid monotony and develop your personal style.

The gymnast should develop his own style with the coaches’ guidance and must be aware of also developing his personal characteristics. This means that the gymnast should strive to produce his personal abilities and use his natural physical gifts for work on the apparatus. Perhaps an example of this is Cerar who started the “vogue” of using the outside of the parallel bars or one bar during his optional exercise. Another trend towards personal development is found in the “Menichelli style” floor exercise. (This was mentioned during the conference as the type of floor exercise now becoming prevalent on the event.)

When the development of the gymnast reaches a point of personal development and he knows what his limitations are the coach must take over and continue this development in order to lead the athlete beyond what he thinks is his finality in routine construction. “The so-called ‘stock’ exercise must not be seen in the evolution of artistic gymnastics, and coaches and judges must take the hint.”

Smolevsky of the Soviet Union: Floor music for men

Smolevsky: One of his proposals, on behalf of the Soviet Union, was:

Floor exercise with music

Smolevsky of the Soviet Union: Better landing mats

Use soft landing mats to prevent injury.

Separately, Don Tonry wrote an article about improving landing mat safety earlier in 1969.

Here’s the thrust of his argument:

In the days when a full twisting somersault on the horizontal bar, forward handspring on the vaulting horse and backward somersault with one-half twist on the parallel bars were supreme, perhaps this was an adequate landing surface. Today we are adding more somersaults, twists and elevation to our dismounts, thereby increasing the difficulty and the force of the landings. Our gymnastics is rapidly improving, but our landing surfaces have remained very close to what they were fifty years ago.

Modern Gymnast, January 1969

2 replies on “1969: The Problems with Vault in Men’s Gymnastics”

Also coming was the handspring front that Okamura did at the FISU Games in 1970

This is fascinating, thank you!!