The 1968 men’s Code of Points exploded.

Gymnastics was quickly evolving, and the Men’s Technical Committee was trying to be more prescriptive on what they wanted to see and in which direction they wanted the sport to go.

I’ll do my best to give you the CliffsNotes version of a 194-page document.

What were some of the big changes?

- Gymnasts could no longer repeat compulsories

- In apparatus finals, 0.3 would be awarded for risk, originality, and virtuosity

- In 1966, Arthur Gander stated that no gymnast should be a world champion unless he showed those three elements: risk, originality, and virtuosity.

- In 1968, this guiding principle was codified in the Code of Points through bonus points during apparatus finals.

Let’s dive into the details…

Could gymnasts repeat routines?

- Gymnasts could no longer repeat compulsory exercises. (They could previously.)

- Gymnasts could repeat exercises in the event of “extraordinary circumstances, such as a defect in the apparatus or the platform, or other unforeseen mishaps” (Art. 18). The superior judge was responsible for making the call.

How was the 10.0 broken down?

There weren’t any changes in 1968 for the optionals portion of the competition. It was still:

- 5 points for execution

- 3.4 for difficulty

- 1.6 for the combination

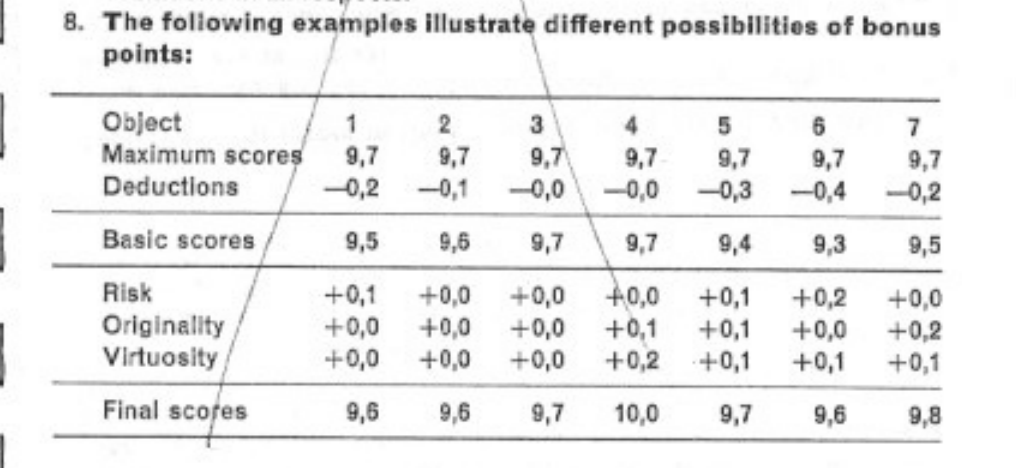

During apparatus finals, however, the equation changed. If a gymnast simply met the requirements during finals, his maximum score was a 9.7:

- 4.9 points for execution

- 3.3 for difficulty

- 1.5 for combination

- All deductions were still in effect

To have a routine judged out of a 10.0 during apparatus finals, the gymnast needed to earn bonus points. He had to go above and beyond, showing:

- Exceptional risk

- Exceptionally original performances

- Exceptional virtuosity (artistic proficiency)

Here’s how the bonus categories worked:

- Gymnast met one bonus category = 0.1 to 0.2 bonus points.

- Gymnast met two bonus categories = 0.1 to 0.3 bonus points.

- Gymnast met three bonus categories = 0.3 bonus points — 0.1 for each category.

How much difficulty was necessary?

For the team/all-around optionals (IB)…

- 6 main parts (A parts)

- 4 parts of difficulty (B parts)

- 1 part of superior difficulty (C part)

During apparatus finals, gymnasts had to perform two C parts.

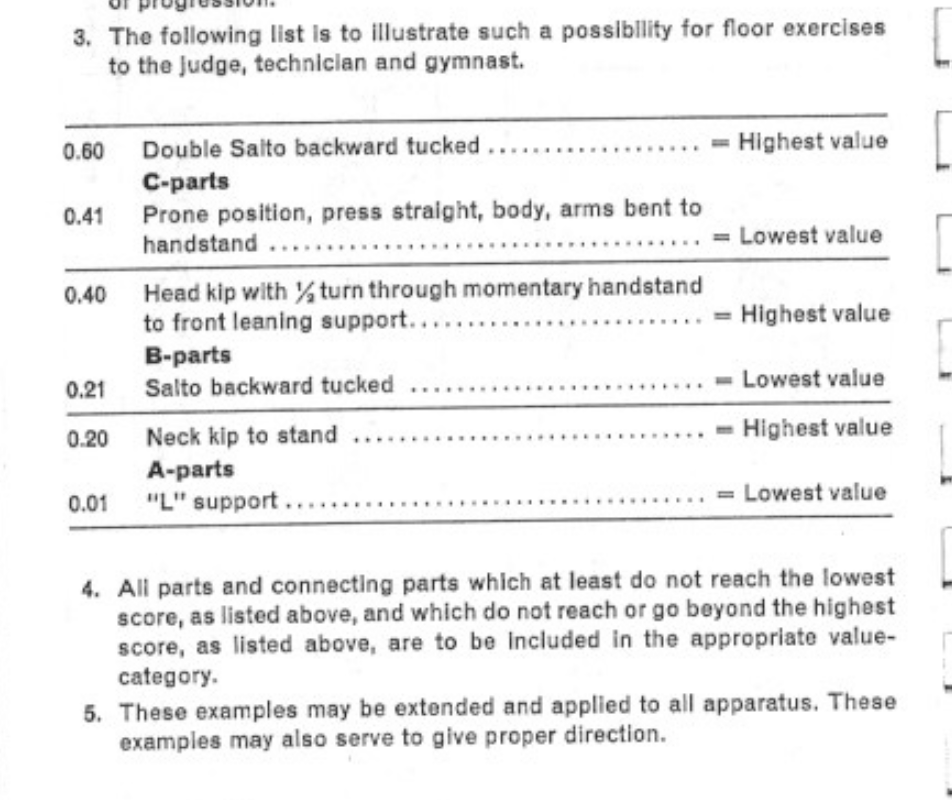

However, not all C parts were created equally.

Instead of adding letters beyond A, B, and C, the men’s technical committee divided each letter into sub-levels of difficulty.

- In other words, some C parts were harder than other C parts — just as some A parts were harder than other A parts, and some B parts were harder than other B parts.

- Here’s an example from FX

- For example, if my C part was a double back and your C part was a press to handstand from prone, the judges could be more lenient with the execution of my double back. (See section below on leniency.)

- Generally speaking, judges were expected to “determine how much courage, strength, skill, control, sense of proportion, orientation, and persistence the gymnast needs. Only this will bring the judge close to a realistic evaluation.” (Article 71.E.2)

Also, don’t just chuck skills

The difficulty of an exercise must never be escalated at the expense of correct form or technically correct execution.

Article 29.1, 1968 Code of Points

How were routines supposed to be constructed?

It depended on the event.

Side Horse (Pommel Horse)

- Clean swings without stops

- Circles of one and both legs

- Forward and reverse scissors – twice in succession

- Double leg circles must be predominant

- All 3 parts of the horse must be used

Rings

- Alternate between swing, strength, and hold parts

- No swinging of the rings

- At least two handstands, one through strength and the other through swing

- One strength part must be at least B difficulty

- During finals, the gymnast must do a swinging C part

Parallel Bars

- Must show swinging, flight, holds, and strength with swinging and flight being predominant

- At least one strength part

- At least one “B” flight where both hands is released simultaneously

- No more than three stops

- At least one “C” swinging element in the optionals and apparatus finals

Horizontal Bar

“The exercise must consist exclusively of swinging without stops.”

That’s it. Those were the composition requirements for high bar.

Floor Exercise

Rhythm was a buzzword. (You can see a very academic definition of rhythm at the end of the Code.)

- “A harmonious rhythmical whole alternating among movements of balance, hold parts, strength parts, leaps, kips, handsprings, and tumbling movements.”

- Yes, you read that correctly: leaps used to be one of the movements that should be included in a floor routine.

- However, as Arthur Gander would explain in 1969, “But men must be careful of going too far with the feminine trend” (Modern Gymnast, June/July 1969).

- So, while women’s gymnastics was trying to retain its feminine identity, men’s gymnastics was trying to retain its masculine identity. (Recognizing that both of these are social constructions whose definitions change with time and geography.)

- For lack of harmony, rhythm, and flexibility, judges could deduct every time up to 0.2

- For lack of harmony, rhythm, and flexibility during the entire exercise, judges could deduct up to 1.00.

- Yes, you read that correctly: leaps used to be one of the movements that should be included in a floor routine.

- Total use of floor space

- “Personal and postural expression”

- My thought bubble: I take this to mean that they don’t want cookie-cutter routines. Each floor routine should seem special and unique to the gymnast.

Could you repeat skills?

Parts could only be repeated once.

A part, already performed, may be repeated only once. The parts preceding and following must be different.

In other words, if I wanted to do two layout fulls in my floor routine, I would have to add, say, a back handspring out of the first layout full.

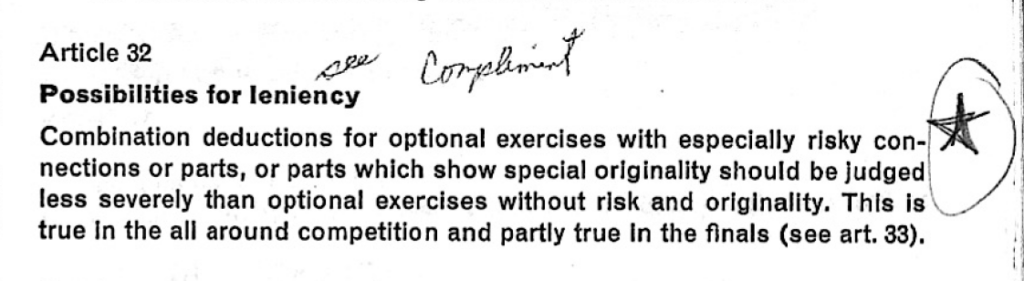

Were execution deductions supposed to be taken evenly across the board?

Eh…

As we saw in the 1964 Code and during the 1966 Men’s Technical Meeting, risky or original connections and elements were scored more leniently (even though the Code also tells gymnasts not to chuck skills).

There was also leniency for virtuosity.

Into the weeds: What is virtuosity?

If you want to venture into the jargon-filled weeds of the 1968 Code of Points, take a look at exactly what the FIG meant by risk, originality, virtuosity, harmony, and rhythm. Those definitions were at the very end of the Code of Points.

For this post, we’ll just look at virtuosity. Essentially, virtuosity encompassed how someone performed a skill or a routine.

To break it down even further, there were three main factors:

- Whether it seemed like the performance came from someone’s soul

- Whether the audience felt impacted by the performance

- Whether the gymnast made it look effortless

- This is why you’ll repeatedly hear commentators say, “The gymnast makes it look so easy!” That was what the judges wanted.

The more verbose explanation:

Virtuosity applies to the area of execution. There are virtuosos in all areas of art, in music, in rhetoric, in dancing, in gymnastics, etc. The virtuoso exhibits an unusual talent for artistic execution. A musician becomes a virtuoso when his brilliance rises above the level of technical accomplishment and so deeply impresses us that our very souls are moved. To do this, he must put his own soul into his work. A dancer shows his virtuosity when he, in his presentation, is able to express his virtuosity with lightness and superiority in movement so that, although driven to maximum exertion, the impression exists that he has yet to fully extend himself. It is similar in the case of gymnastics… He is able to capture the souls of the spectators and to fill their hearts with joy.

Virtuosity was extremely subjective. What moved my soul might be different from what moved your soul.

Download the Code of Points

All right, that gives you a starting point for watching some old routines from this era.

You can download the Code of Points below. I apologize for all the scribbles in the Code. The crossed-out items have to do with the updates from the 1971 Code of Points supplement.

Apparatus Norms

Here are a few of the apparatus norms that were in place in 1968.

Note: The apparatus norms didn’t necessarily change when there was a new Code. They could change at any time. But I’m placing them here so that the apparatus norms have a home for now.

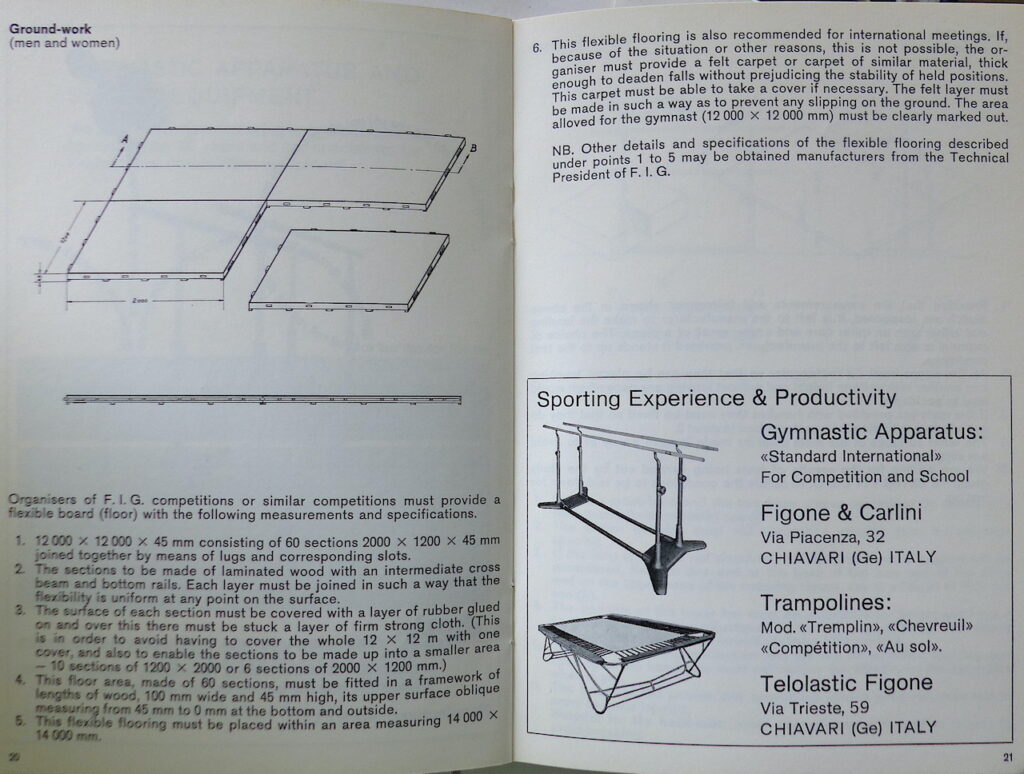

Floor Exercise

At FIG events, the gymnasts competed on the double flex floor (sometimes called the “double swing floor” or the “Reuther floor”). It was essentially two floorboards sandwiched together with small inserts between the layers. (Eventually, there would be foam blocks and rubber balls between the layers.) You could see it as a precursor to the modern spring floor.

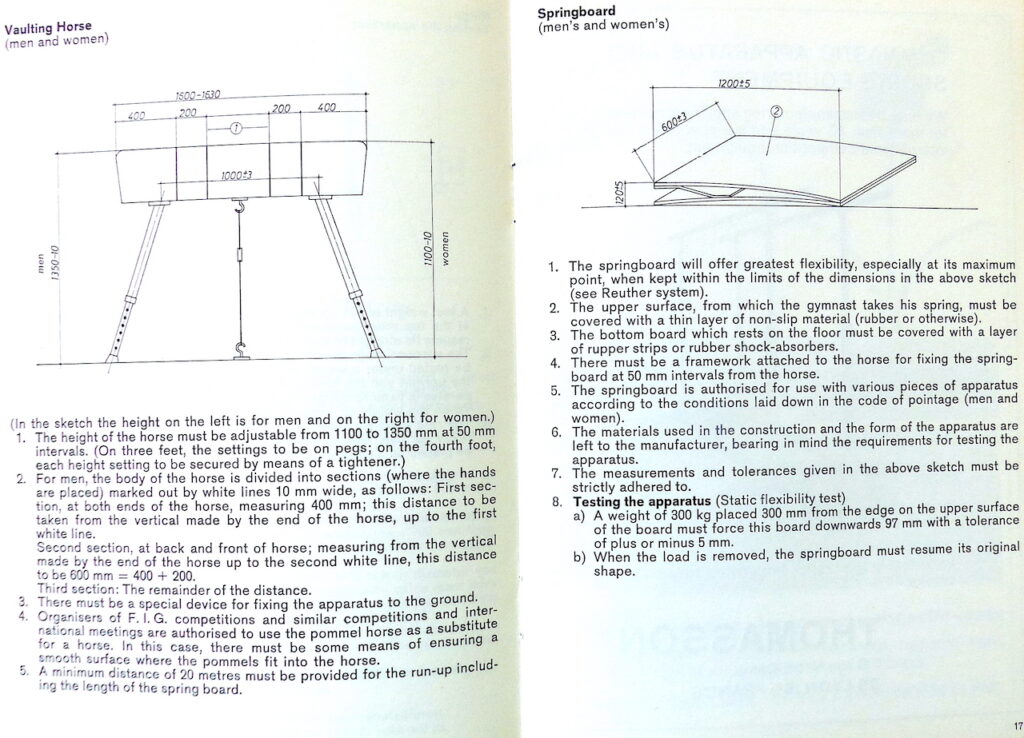

Long Horse Vault

Here are the vault and Reuther board requirements for FIG events.

Interestingly, the men’s vault hasn’t changed heights in decades. The men’s vault was 135 cm, and today, the highest part of the table is still 135 cm.

As I’ve explained before, the men’s vault had sections at the time. There was an automated system to indicate if the men placed their hands “on the limits of the zones.” The specifications are below.

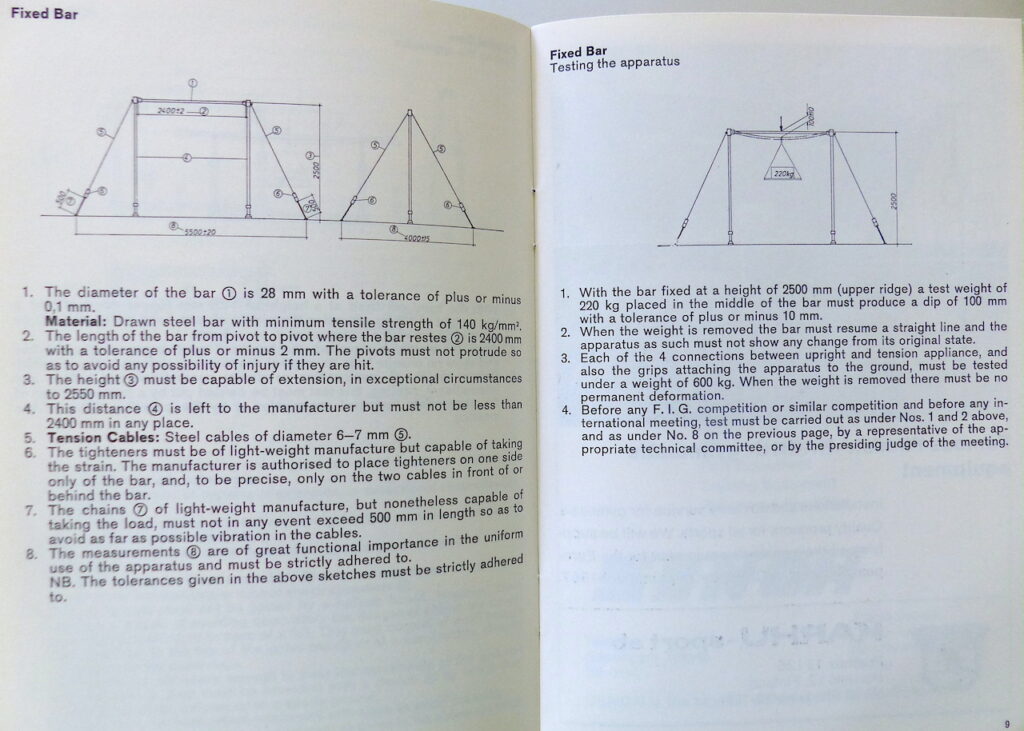

Horizontal Bar

I find the standardizing tests fascinating.

Many thanks to Hardy Fink for supplying these photos.

More Codes of Points

More on 1968