This lengthy profile of Ecaterina Szabó, published in Képes Sport (Sport in Pictures) in May 1990, offers a detailed firsthand account of life in Romanian gymnastics during the late 1970s and 1980s. The article, based on interviews conducted by Levente Deák for Romániai Magyar Szó (The Hungarian Voice of Romania), traces Szabo’s journey from a small village in Transylvania to Olympic glory at the 1984 Los Angeles Games, where she won four gold medals.

Notably, the article confirms Szabo’s actual birth date as January 22, 1968—making her 16 years old at the time of her Olympic triumph, not the older age sometimes claimed in contemporary sources. The narrative provides extensive detail about the grueling training regime at the Karolyi gymnastics school: wake-up calls at 6 AM, training sessions lasting until 10 PM as punishment, mandatory afternoon naps, and a schedule that prioritized gymnastics over traditional schooling.

As you’ll see, compared to today’s top gymnasts, Szabó competed non-stop, traveling to a total of 70 countries. It’s no wonder that, by the time the World Championships in 1985 rolled around, she “was simply exhausted.”

As was often the case at that time, gymnasts’ biographies were woven together with Béla Károlyi’s story. Throughout the piece, the writer includes several parenthetical statements that paint Béla Károlyi in a remarkably positive light, characterizing him as a dedicated coach who made tactical decisions in the best interests of his gymnasts.

However, this generous portrayal omits crucial context that we know today: before the Károlyis were transferred to General School No. 7 in Deva, the Romanian government’s patience with the Károlyis was wearing dangerously thin. In March 1977, Teodora Ungureanu fled during training in Cluj, boarding a train to Onești. The Securitate intercepted her at the Târgu Mureș train station and escorted her to Bucharest. According to the Securitate report: “The gymnast gave as the reason for leaving the fact that she could no longer stand working with coach Béla Károlyi,” who “persecutes her baselessly.”

The situation continued to deteriorate during a tour of Spain in 1977. Securitate officer Ioan Popescu reported that Béla Károlyi “showed inappropriate conduct towards Nadia Comaneci and Teodora Ungureanu, consisting of swearwords, insults, even beating them, because their weight was unsuitable for the competition.” Ilie Istrate, a National Council for Physical Education and Sport (NCPES) instructor and Securitate informant, reported that “the girls were found weeping in their rooms because of hunger.” (See Olaru’s Nadia Comăneci and the Secret Police for more.)

Read against this historical background, Szabó’s account becomes all the more poignant—a testament to both her remarkable athletic achievements and the complex, often contradictory relationships that defined elite Romanian gymnastics in this era.

In many ways, this set of articles becomes Szabó’s way of reclaiming her story—from her erased Hungarian heritage to her falsified age, from the name she was given to the one she was born with (Katalin), and from the rewards she earned to those she never received.

The Story of a Sports Career

“Katalin Szabó’s recollections were recorded and annotated by Levente Deák, a contributor to Romániai Magyar Szó.”

[Note: This series of articles does not dive into the details, but Ecaterina Szabó was not her real name. From the March 22, 2003 edition of ProSport: “Ecaterina Szabó, the multiple Olympic, world, and European gymnastics champion of the 1980s, actually has a different name: Katalin Szabó. She agreed to be given a new identity in order to be included on Romania’s national team—though not before refusing a truly absurd proposal from the communist regime. The athlete, who is of Hungarian ethnicity, was offered a fully Romanianized name: Ecaterina Sabău.”]

I. The Lost Childhood

[Published May 15, 1990]

There Is Something in This Girl

“I have come to love Rodostó so much that I can never forget Zágon,” confesses Kelemen Mikes of Zágon in his now-proverbial 37th letter, dated May 28, 1720—a sentence I only truly understood as an adult. I left home early, barely six years old, and I have been on the road ever since, but I cannot, will not, and do not wish to forget my native village.

[Note: Kelemen Mikes (1690–1761) was a Transylvanian Hungarian nobleman, writer, and political exile who followed Prince Ferenc Rákóczi II to the Ottoman Empire after the failed anti-Habsburg War of Independence. During his decades of exile in Rodostó (today Tekirdağ, Turkey), he wrote the Letters from Turkey (Törökországi levelek), a series of essayistic letters addressed to a fictionalized adoptive mother figure, blending memoir, political reflection, humor, and homesickness. These letters, published posthumously, are considered foundational works of Hungarian prose.]

I was born on January 22, 1968, in Zágon, the youngest of three children of Albert Szabó, a railway worker, and Etelka Szabó, a homemaker. My sister, Zita—who, together with her husband, emigrated to the United States a few years ago—is a good ten years older than I am, and my brother, Albert, now a worker at the Sepsiszentgyörgy (Sfântu Gheorghe) slaughterhouse, is about seven years older. Until I turned six, they, too, alongside my parents, took great care of me, the baby of the family.

I was a restless, skinny child who, despite being a girl, was forever climbing trees and constantly had to be searched for. Even then, my love for movement was obvious. In 1972, during a school performance, I appeared before an audience for the first time, doing simple gymnastics exercises. I often joke that it was the most carefree competition of my life. I was four years old…

The neighbors, who knew me and had seen me at that little show, kept telling my parents: There is something in this girl, she’s a born gymnastics talent, dear Etelka, take her to someone, to a specialist… But that had to wait two more years.

In the meantime, my sister, Zita, who attended school in nearby Kovászna (Covasna)—and who, to give my parents occasional breaks from looking after me so they could calmly pursue their craft of broom-making on their newly acquired permit—often took me with her. I would spend the whole school day by her side, including during her PE classes. Her gymnastics teacher, Ms. Gabi (I apologize that I no longer remember her surname), adored me, spent time with me, and urged my parents to take me to Sándor Lup, the well-known gymnastics coach from Brașov, who had helped discover Sonia Iovan and other famous gymnasts.

I remember perfectly, though I was only six, that my parents took me to Mr. Sándor in Brașov twice a week (my father has worked at the Brașov railway traffic office for thirty years and commutes from Zágon). After a few months of training, the respected coach advised my parents to contact the Károlyi couple in Onești, whose names were already well-known, with newspapers writing frequently about their gymnastics school.

A Girl Who Dreamed of Gymnastics Instead of Dolls

My parents took the good advice to heart and one morning brought me by train to the Károlyis. This happened in 1974, when I had barely turned six. I was scared and hardly wanted to enter the gym. As I recall, Béla Károlyi himself welcomed us. I showed him what I could do, then I watched the little girls who already knew so much more than I did—the grace of their movements captivated me so deeply that in the end I didn’t want to leave the gym at all. Encouraged by the master coach, my parents made their decision on the spot: they enrolled me in the Károlyi gymnastics school in Onești.

(The Károlyi couple, Márta and Béla, were often written about at the time for their pioneering training methods. It’s well known that in the late 1970s—more precisely, in the summer of 1978—they moved from Onești to Deva, where they continued their feverish work with renewed energy and much better conditions. In those years, we had several opportunities to talk with them. On December 31, 1979, in an issue of Előre, Béla Károlyi spoke about preparing the gymnasts for competition: “You ask how many years it takes to bring a gymnast to the top? With Nadia’s age group, it took us seven years to produce our first outstanding results. Today it takes five years—but only because we now spend more time, about nine hours a day, in the gym. No more than that is possible, and no more is allowed. The girls must study and play as well.”)

Six full and difficult years followed—my Onești years—which lasted until January 3, 1980, when I moved to Deva. But let me not rush ahead! Let me recall the first days of six-year-old Kati in Onești.

I was placed in the dormitory, where a cleaning lady who spoke some Hungarian, along with a few older Romanian girls, looked after me. For one month, I still attended kindergarten, and only in the autumn of 1974 could I be enrolled in school. I remember very well how much I longed for my parents. Whenever they could, they came to visit me, and parting afterward was always the hardest moment. They would invent a story that they had to go into town for something, and I would wait and wait for them, swallowing my sadness in tears. The cleaning lady and the girls cared for me, and I grew attached to them, but the warmth of home—my mother, my father, my siblings—was painfully missing.

Later, my sister, Zita, continued her schooling in Onești—she completed 11th and 12th grade there—and for two years we were together in the dormitory, sharing a room with seven other young gymnasts. With her there, time passed more quickly, without sorrow. Mornings, I went to school, and afternoons to training with the other six- and seven-year-old girls whose parents had enrolled them in this gymnastics school from all over the country. I was no different from them—just one of many little girls put through hard training, a child who dreamed of gymnastics instead of dolls…

It was as if we had been enchanted: we began and ended the day with gymnastics. We lived in a wonderful world, a dream world, with gymnastics at its center. We were small, and we rejoiced over the tiniest success. And at that age, we didn’t truly understand that we fought hard for those small triumphs, nor that a sporting career essentially demanded sacrificing one’s childhood and doing without many things that a normal child growing up in a family simply receives—things a child at home naturally has. Today I know that success wasn’t given to us for free; we had to work hard for it and pay a price for it.

From Dawn Until Lights Out…

No, I do not regret for a moment that I bound myself to gymnastics for life. But I do want to make everyone understand—especially now, when I receive letter after letter from parents asking for professional advice or hoping to enroll their daughters in my group—that only those who are truly talented can hope for success, and even then, only if their natural gifts are matched by exceptional diligence, endurance, work capacity, and sacrifice. And even among such girls, many will fall away. Several of my former and current friends know well what it means to toil endlessly, to push themselves to exhaustion, yet in the end to receive very little—or even nothing—lasting, no success, no glory. And those who do not make it cannot count on finding work even as substitute sports teachers unless they have formal qualifications, which many do not, since their high school diploma was not earned in a regular academic school. (I am fortunate enough to have that kind of diploma as well.)

I spent six years in that Moldavian town, if I remember correctly, enrolled at a high school with an emphasis on philology–history—but the school’s curriculum was not what mattered to me. What mattered was the activity taking place inside that school: gymnastics.

In the early period, wake-up was at six in the morning, breakfast at seven, then classes until noon. From school, we went directly to lunch, then to the dormitory for barely half an hour of rest. Ten minutes before two, we lined up and headed to the gym. Exactly at two o’clock—little ones and older girls together—we stood in two groups waiting for Ms. Márta and Mr. Béla to arrive. They were always punctual, and training began immediately. After a hard twenty-minute warm-up, we split into smaller groups at different apparatus. Sometimes we trained only on beam, or on uneven bars, or on the other two events; sometimes we rotated, repeating the same exercise, movement, or element a hundred times—I don’t even know how many. This lasted until five in the afternoon. After that came preparation for the next day’s schoolwork. Then dinner, washing up, and at half past eight or nine: lights out. We were so exhausted that we fell into bed and immediately into sleep—no one needed to be rocked.

Soon, our coaches changed our daily schedule: fewer hours were devoted to studying, and more and more time was spent in the gym. We, younger girls, were moved into rooms with the older ones—Itu Cristina, Éberle Emilia, Gheorghiu Gabi, Vladăruiu Marilena, to name just a few. We trained from eight to ten in the morning, but instead of going to school afterward, the teachers came to us in the dorm. After lessons, lunch was served there as well—the staff brought it straight from the kitchen. Then came two hours of obligatory sleep, followed by another three hours of training in the afternoon.

But since we had to prepare the gym before five o’clock, those “three hours” usually meant more. And on days when, for reasons unknown to us, Mr. Béla made me—or others—“work overtime,” it meant much more. He certainly knew the reason—some mistake we had made, something we had not done well enough. Being a strict coach, on such days, as punishment, we sometimes trained until ten at night. Even though we were in top physical condition, every part of our body ached in the evenings. We could barely—I’m not sure we even truly could—rest enough by morning. And this went on day after day.

Sundays were different: only morning training, and sometimes even that was cancelled. On those days, we flooded into town, usually to the city park. The whole town knew: training was cancelled, the girls were taking a breather. But as 1976—the year of the Montreal Olympics—approached, these free Sundays became rarer, and the workload grew heavier. Day by day, competition fever rose, tension increased—and even we little ones could feel it…

Alone Again

In 1976, during the Montreal Olympics, I was barely eight years old, but I still remember clearly how even we little ones were completely swept up in Nadia Comaneci’s sporting triumphs. We knew her well—we trained together, we saw her up close, we tried to imitate her walk, the way she held her head, her movements, her routines. Of course, at that age, we couldn’t yet succeed in copying her, but we didn’t give up. With the absolute conviction of small children, we declared at every step that we wanted to become gymnasts just like her. At that time, she was Romania’s brightest gymnastics star, and deservedly so; the national and international press was full of her.

Although she lived with her parents in the 1970s, she regularly came to the gym for training, and I remember that even then—even in her prime—she worked tremendously hard. At that time, at least as we saw it, her relationship with her coach was still good; she listened to him and followed his instructions.

I was already in third grade when my sister, Zita, left the town after finishing high school, and once again I was left alone—meaning, I had no close family member beside me. My days and weeks passed uneventfully, monotonously. I trained diligently, I studied diligently, but at that time, no one paid much special attention to me. In the spring and summer of 1978, the Károlyi couple moved to Deva together with the national and Olympic squad, but they did not take me with them. It’s true—I was small, and I wasn’t particularly good, so none of the remaining coaches in Onești wanted to take me under their wing for more than a few days at a time. I would train with one coach for two or three days, then I’d be shifted to someone else. This unfortunate situation lasted for several months.

Finally, I ended up training under the master coaches Mihály Ágoston and Maria Cosma; I trained with the two of them alternately for a full year and gradually improved more and more.

(Béla Károlyi cannot be blamed for leaving ten-year-old Kati in Onești in 1978. As we will later see, even if that decision—judged by today’s standards—might appear a mistake or an oversight, he corrected it the following year, at the end of 1979. In the spring and summer of 1978, however, Károlyi and his team had far greater concerns: they had to establish the new gymnastics center in Deva. In the December 31, 1978 issue of Előre, he spoke about this work:

“…On September 15, 1978, Deva’s newest primary school opened. Many applied, which shows how popular gymnastics is. Since early April, we selected 205 children out of nearly twelve thousand applicants; these are the ones who study and train here today. Thanks to the remarkable support of the local authorities, we were able in a short time to prepare excellent accommodation, a well-equipped dining facility, and—no less importantly—a gymnasium for the girls who moved here: Emilia Eberle, Cristina Iuțu, Marilena Vlădăroiou, and Gabi Gheorghiu. One month before this year’s World Championships in Strasbourg, I was entrusted with preparing the national and Olympic squad, and that is how Nadia also came to Deva—she lives here and works with me again. In addition to the girls mentioned, Marinela Neacșu, Melita Rühn, Enikő Kiss, Ibolya Gyűjtő, Claudea Dragomir, Dumitrița Turner, and Rodica Dunca also belong to the Olympic team. This is the group of twelve girls we work with here in Deva. (…) We train the Olympic squad together with my wife, the ballet master, and the pianist, but we also must find time to monitor the development of the grades I–IV girls. After all, the next generation grows up here!”

We now know that Béla Károlyi monitored the development of the younger generation in all the gymnastics centers, and when the time was right, he brought those girls under his wing. Kati among them…)

II. From Disappointment to the Top

[Published May 22, 1990]

Not Giving Up!

My first real competition—a selection meet—took place in 1979 in Bacău. The stakes were high: the top three finishers would qualify for the Junior Balkan Championships. My opponents were Cristina Grigoraș, Lavinia Agache, and Mirela Barbalată. Although I finished second, I was not taken to the competition. To this day, I do not know why; no one ever talked to me about it or gave me an explanation. I was eleven years old, and my first competition became the first disappointment of my life. But despite everything, I did not give up.

That same year, I was taken as a reserve to a competition in East Germany, in Halle. But since I had only just recovered from an injury, I did not compete at all.

At the end of 1979, Mr. Béla called my parents several times and told them he wanted to bring me to Deva. At that time, my parents still didn’t have a telephone, so they had to speak from the Zágon post office. My mother did not want to make a decision without me, so she told the coach that the move depended entirely on me. At first, I did not want to go—I was afraid of the unknown and, admittedly, a little afraid of the coach’s strictness. Even when my father came to pick me up for winter vacation in December 1979, I still held to that decision.

But at home, they persuaded me. The decisive argument was that, as a gymnast, I would be able to travel the world.

We were supposed to call Mr. Béla on December 30 or 31. He asked me:

— Hi, Katya — because that’s what he called me — what have you decided? Are you coming to Deva?

— Yes — I said.

And on January 3, 1980, my mother, father, and I arrived in Deva with all our luggage.

We did not know the town, but it was easy to find the school—everyone we asked knew it stood at the foot of the famous Deva fortress, next to the brand-new gymnasium where the stars at that time trained, including Nadia, Emilia Eberle, Rodica Dunca, and Valerina Vlădăruț. When we reached the school, the gatekeeper directed us to the Károlyis’ residence. They lived right next to the school and gym.

I remember there was a lot of snow—unusually much, even for Deva. The Károlyis had returned only a few days earlier from Fort Worth, the site of the December 1979 World Championships, where the girls had won the team gold medal, despite Nadia being injured mid-competition and the team having to finish without her.

(From Előre, December 10, 1979, Béla Károlyi said about the team world title:

“I must speak about the world team gold… because we proved that our women’s gymnastics is not built on one or two individuals, but on an entire team—meaning a sufficient number of well-prepared gymnasts. In Fort Worth, during the competition, we lived through moments of dramatic tension—but that is the case at every world meet. Nadia’s injury created a difficult situation, especially since it coincided with Eberle’s fall from the beam. We had seconds to decide, attempting the impossible—despite the pain, Nadia had to compete. What followed is known: Nadia was magnificent; she received 9.95, reopening the fight and keeping us in contention for the gold. The girls did afterwards exactly what they were capable of and had trained for, and what was important—they stayed calm. Then came Dumitrița Turner’s gold on vault and Emilia Eberle’s on floor.”)

I myself was later in a similar situation—forced to continue competing despite an injury for the sake of the team’s placement—and I mention this only to remind readers of the drama and tension that accompany gymnastics competitions.

By January 1980, the Károlyis, the girls—everyone in Deva—was full of happiness and determination, preparing for the Moscow Olympics. At twelve, I could not be selected for the Olympic team, of course, but thanks to my coach, I was taken along to observe, learn, and gain experience.

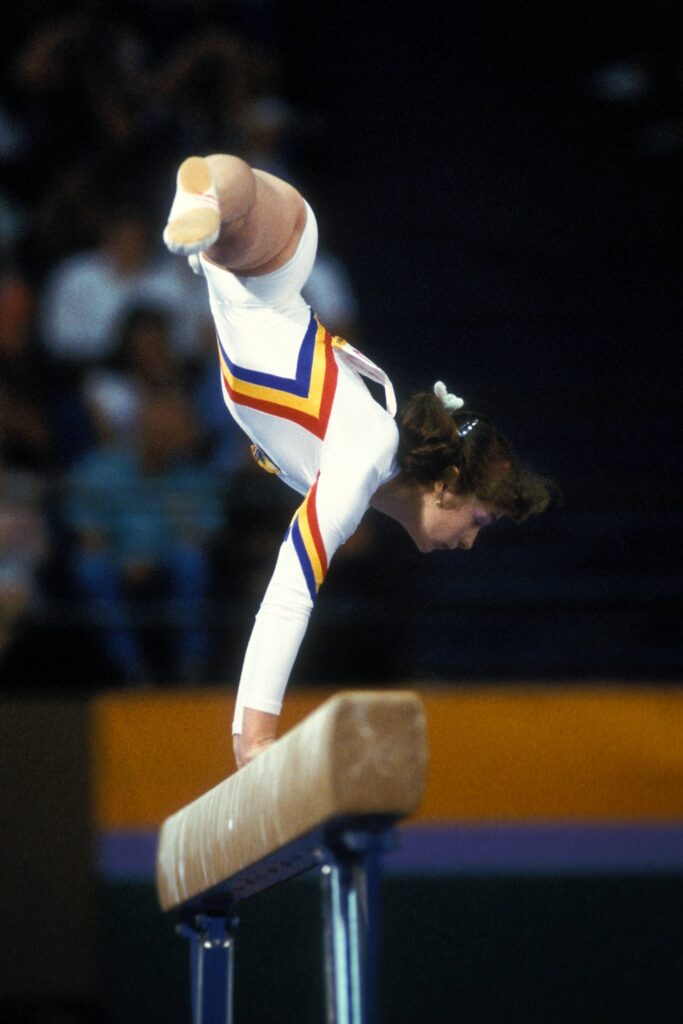

Earlier that year, at Romania’s International Championships in the capital, I competed officially out of ranking and received the first three perfect 10.00s of my life. Then, in May, at the Junior European Championships in Lyon, France, I won four gold medals: all-around, vault, beam, and floor. From that moment, people began to count me among the great promises of Romanian gymnastics.

From Country to Country

Since then, I’ve regularly written down the names of all the countries I visited as a competitor—and now I see how useful that little notebook is. Leafing through it makes remembering easier: I traveled to a total of seventy countries. In the end, my childhood wish was more than fulfilled. As a gymnast, I truly traveled the whole world.

But in 1980, I experienced partial successes and failures, as well. I remember that, in the Romania–Italy meet, I finished only seventh; I made mistakes on floor and bars. That same year, I also competed at the Junior World Cup in Japan. I competed with cracked heels, and although I won beam and placed second on bars, vault and floor were beyond me—the pain simply made them impossible. It was the first time I competed while injured, and to stay in the competition, I had to choose a very simple vault—one for which I received only a 6.0.

This is the moment to say: no gymnast has ever been born who was equally perfect on all four events. Or to put it differently: every gymnast has her “bogey apparatus.” For Nadia, perhaps it was vault. For Eberle, the uneven bars. For Daniela Silivaș, my best friend, it was vault. For me, it was bars. And although later I sometimes managed better results on that event, I never fully overcame my “bars phobia.”

I was the kind of gymnast who did every exercise without complaint, who was always disciplined and obedient, yet in 1986 and then in 1987—toward the end of my career—I often clashed with my coach precisely because of the bars routines. Gymnastics is a sport where, one day, you suddenly feel: I’ve had enough; I can’t do this anymore. But until that day arrived, I still competed in many meets—and often won.

(At the Moscow Olympics, Romania’s women’s gymnastics team won “only” the silver medal—a result that was regarded at home as a failure. After the Games, I had a long conversation with Béla Károlyi, and the editorial staff of Előre prepared an interview with him which, as far as I remember, was never published.

Thinking back to that conversation now, I remember his depressed mood—how painful it was for him to be sidelined, how deeply he felt that the result, the work, the team’s performance simply had not been appreciated. It was true that after Fort Worth, after the team world title, Romania went into the Olympics as the favorite. But as Károlyi told me—though not in these words, we both understood without saying it—that no one wanted to take into account that the Soviet girls, on their home turf, in front of their own crowd, after their loss at the world championships, would do everything possible to reclaim world supremacy. The shadow of high politics fell onto sport and sporting spirit. And such a partial success or partial failure—this “only” silver medal—was not enough to make people forget, overnight, the results achieved, the hard work, the effort, the sacrifice.

In such a mood, it is perhaps not surprising that shortly afterward, following a competition, he did not return home and chose instead to emigrate.)

In March 1981, I took part in a long and exhausting gymnastics exhibition tour in the United States and Venezuela. We performed a total of fifteen times, with tremendous success. Unfortunately, I no longer remember the details; the flights, the hotels, the restaurants, the gyms all seemed so alike. Surely, they were not all the same, but that is all we perceived of them. Everything revolved around gymnastics—entertainment, going out, dancing were out of the question, even for the older girls.

Preparation for competitions also followed a well-established routine. The serious work began two or three months before the event, building on the foundation we had already developed. The coaches—and usually the gymnastics federation—selected a larger preliminary squad, and we had to compete among ourselves for the right to travel and to compete. It was sport rivalry at its purest, and to achieve the expected—or at least reasonably assured—results, the girls in the best shape were usually the ones chosen for the team.

At that time, women’s gymnastics was considered the most successful sport in the country, and results—by which, unfortunately, people meant only gold medals—were awaited with bated breath by the entire nation. And we knew this. The responsibility weighed heavily on us during competition—the knowledge of what people at home would say if we failed.

There’s something about this girl

After we came back from America, my coaches became Andrian Goreac and Mária Cosma; the former was also for years the head coach of the Olympic and national teams. From the little notebook I’ve already mentioned, I can see that, in 1981, I also traveled to Greece, where we won the team gold medal at the Junior Balkan Championships. Turkey came in 1982, when, in Ankara, I won four junior European Championship gold medals again: in the all-around, vault, beam, and floor. By then, I already knew it was only a matter of time before I would be entered in senior world competitions as well. After a demonstration series in Cyprus, this happened in 1983 at the European Championships in Gothenburg, Sweden. I won gold on floor and uneven bars, silver on vault, and bronze in the all-around—and I remember how much it hurt that I did not place on beam because I fell. But even so, the medal haul from my very first senior competition could be considered beautiful.

Then came the dual meets between countries, the exhibition and invitational competitions, in dizzying succession, with varying degrees of success. In 1983, we competed against Spain, France, and England, then I took part in gymnastics exhibitions in Brazil and Argentina, and I was also at the World Championships in Budapest, where I won gold on floor, silver on vault and bars, and bronze in the all-around.

A special detail of that trip to Budapest is that my family—my mother, my younger brother, and my maternal grandparents—happened to be in Budapest with passports. They didn’t have tickets, but in the end, we managed to get them into the sports hall, so they were able to watch the whole competition with their hearts in their throats.

In the remaining time before the Los Angeles Olympics, it was competition after competition. I traveled to and competed in Israel, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Spain twice, West Germany, and Japan, and based on my form, I prepared for the Summer Olympics with great confidence and determination, where I went on to win four gold medals.

I had reached the top.

III. As an Olympic Champion in Romania

[Published May 29, 1990]

“I was afraid of the fake coaches…”

Looking back on my sports career, I consider my four gold medals from the 1984 Los Angeles Summer Olympics the most precious—because that was the moment I was at my absolute peak—even if, in the all-around, the title was won by my former coach’s new student, the American Mary Lou Retton. In return, we won the team gold medal; I won gold on floor, vault, and beam (Simona Păuca also won gold on that apparatus), and on top of all that, I took the silver in the all-around.

I remember precisely: we left for the Olympics on August 18, 1984, with a large delegation, including the ever-present security officers who traveled to every world championship and international dual meet under the guise of “assistant coaches” or “technical supervisors.” We knew who they really were, and we were wary of them. That fear is what held me back at the Olympics when Béla Károlyi—my former coach—tried to approach me and speak with me. I shut down completely. Fortunately, he wasn’t offended—he knew exactly how things worked back home. But the truth is, we athletes were kept under strict surveillance the entire time; there was no question of individual sightseeing or taking time to relax.

I also remember our departure date so clearly because years later, I learned that my brother-in-law, Zita’s husband, Oszkár Balogh, arrived in Vienna as a refugee just two days later, on August 20, 1984. From there, in 1985, he left for the United States and settled in Fairfield. He works hard as a subcontractor in construction. My sister, Zita, followed him in 1986 with their daughter, Abigél. According to my mother—who recently spent three months visiting them—they are doing well financially and health-wise, but the women suffer badly from homesickness.

Competing as “Kati Szabó”…

After this little family detour, a few words about the competition itself. I was in good form; everyone knew it, because I had competed a great deal before the Olympics. Recently, I heard from my former coach that some people in the federation didn’t look kindly on this frequent participation, and said to him, “Isn’t there anyone other than this Kati Szabó you can send for once?”

It seems there wasn’t—and in the hope of success, they had no choice but to accept me as I was: Kati Szabó.

It is memorable, too, how politics intervened: the Soviet and East German girls (the strongest at the time, aside from us, of course) did not participate in the Olympics, leaving the Americans and Chinese as the main rivals. To this day, many people ask me what would have happened if the gymnasts from those countries had also competed—would I still have won four gold medals? Perhaps not four, but one or two, definitely.

The competition itself was like all the others: hard, nerve-wracking, full of tension. One example: on floor, I was to follow the American girl Julianne McNamara, who had just received a perfect 10. I was already standing at the edge of the podium when suddenly, a power outage plunged the arena into darkness. Security guards immediately surrounded me, and moments later—even in the dark—my coach at the time, Adrian Goreac, found me and reassured me: “Kati, nothing can go wrong. You’re in great form. Don’t let this sudden blackout unsettle you—you’re going to win!”

When the lights came back on after exactly eight minutes, I performed a flawless routine and, with another 10, won another gold. In the all-around, however, I only took silver, because on bars—where, as I’ve mentioned, mistakes plagued me throughout my entire career—I erred once again. Still, I was comforted by the team gold and the apparatus titles.

At this competition, thanks to the organizers, we even had some time to relax. We visited Disneyland; we had fun and enjoyed ourselves.

The “Reward” for Gold Medals…

Here I will tell what I received—both there and at home—for those Olympic gold medals. I was told—and this is exactly how it was said to us—that the world-famous Adidas company gives a video recorder to every athlete who wins an Olympic gold medal. So, for four gold medals, I should have received four such machines. I did receive one—it still exists today—but whether the other three were delivered, and who might have received them instead, I still do not know.

At home—and I remember this precisely—I signed for receiving a cash reward of 102,200 lei, of which I actually received 52,000 lei in hand. I later used that amount, along with other money I had saved, as a down payment for a car. But the car, which I was told I could obtain without waiting in line, I still have not received. They told me to wait like everyone else… Perhaps this year, my turn will finally come.

Besides the video recorder, I also received, from the Americans, a hi-fi system, a cassette player, a gold chain, and a gold ring. Oh—and a giant eight-liter bottle of champagne. We will only open that at my wedding; the groom-to-be already exists.

But to dispel the rumors about “fabulous financial advantages”: at home, a medal had a fixed price. For an Olympic gold medal won in competition, they gave 1,600 lei, from which income tax was deducted. At invitational competitions, I also received gifts: in Japan, a camera; in Spain, instead of the promised car, a film camera. These I still have.

And when I retired from active competition, of course, the gifts also stopped. For nearly three years, I was employed as an unskilled worker at a nearby mining enterprise with a monthly salary of 2,121 lei.

Since the middle of February this year, I have been working—legally—as a substitute teacher and gymnastics coach at Deva’s No. 7 Elementary School, with a base salary of 2,140 lei.

To Keep Trusting—but for How Long?

When we returned home from the Los Angeles Olympics, we were welcomed at the airport with a celebratory mood, followed by two days in the capital staying at the Sports Hotel and a meeting with the workers of the August 23 Factory. In broad strokes, that was all. I received no decoration or official honor. From Bucharest, we traveled straight to the seaside for a well-deserved three-week rest, and after that, I was allowed to go home to Zágon.

I have already mentioned that, after every competition, I felt a deep physical and psychological exhaustion, and, as the years went by, this feeling only intensified. But no mention of it was allowed—I had to endure the demands. After every short or long break, every moment of rest, I returned to gymnastics with dread, thinking of the new trials awaiting me. In 1984, the Olympic year, I couldn’t seriously consider retiring—I was only sixteen. I returned to Deva and again took up the dual burden of training and schooling, though, of course, gymnastics came at the expense of the latter.

In 1985, after a competition or training camp in Israel—I don’t even remember exactly which—I competed at the European Championships held in Helsinki, Finland, in May. Initially, I had not been selected for the team, which I did not mind, but at the last moment, I was told I would have to compete. I was tired, deeply out of shape, and this showed in the results: I won only a silver medal on vault, and neither I nor anyone else was satisfied.

Then came more competitions: in the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Greece—though perhaps not in that order. Greece, I remember best, because, at the Balkan Championships, I won all six gold medals: the team event, the all-around, and all four apparatus. Then came Japan again, the World University Championships in Kobe. My results: two golds (vault and beam) and four silvers (floor, bars, team, and all-around). Another world meet with six medals. I have beautiful memories from that competition. I was struck by the courtesy of the Japanese, the flawless organization, and their respect for foreigners—athletes and coaches alike. The photograph included, taken with Japanese police officers, reflects well the carefree mood I felt there.

The 1985 World Championships in Montreal, however, once again did not go as I had planned. I added two more silver medals (vault and beam) to my collection, but overall, my performance was considered a disappointment at home. I know this because on the long flight home, the coaches and accompanying officials kept asking me, “Kati, only two silvers—what’s wrong with you?” Nothing was wrong—I was simply exhausted. But in competitive gymnastics, as long as you are on top, there is no such thing as stopping.

Even so, that same year they entered me in two more competitions, in Switzerland and the Federal Republic of Germany, and in 1986 further meets and exhibitions followed: in distant Indonesia, then again in West Germany, as well as in the Netherlands and Czechoslovakia.

To Stop With One’s Head Held High…

In 1986, at the World Cup in China, I won two more silver medals, then came Spain, Yugoslavia, and England. Luckily, I at least wrote down the countries, because now it helps to revive the memories. It was in 1986 that I made the decision to retire. I felt a deadly exhaustion, and my spinal problems had returned. Besides, by the standards of both then and now, at eighteen, a female gymnast is already considered a veteran.

My coaches wouldn’t hear of it at first—or rather, they agreed only on one condition: that I compete at the 1987 World Championships in Rotterdam. With difficulty, I agreed—I allowed myself to be persuaded—and worked hard for one more year so that I could leave the sport with my head held high.

I believe I succeeded, for in 1987, we won the world team gold medal, and I earned a bronze on beam as well. That was my last competition. After returning home from Rotterdam, I barely had time to rest before I applied to the Bucharest Institute of Physical Education for a program that did not require regular attendance. I was accepted, and I was very happy.

Here, I would like to publicly thank my friend, Viorica Dudas, the school secretary, for her kindness in traveling to the capital in my place to deliver the enrollment papers required for my application.

With good and weaker grades alike in my record book, I am currently a third-year student, preparing for my exams, while my own pupils—eight- and nine-year-old girls—diligently follow the same path I once began myself.

More Interviews and Profiles

2 replies on “1990: Ecaterina Szabó Looks Back on Her Career”

Great interview with Szabo.

There is a brief mention of the Romanian disappointment at the 1980 Olympics which always surprises me as it is one of their most successful.

For the first time ever at the Olympics Romanian gymnasts medal in Team, AA, and on each piece of apparatus in event finals. This they had never achieved before and achieved only once again in the next 11 Olympics. Both in 76 with Nadia Comaneci and Teodora Ungureanu at their peak and at LA in 84, with the majority of the world’s top gymnasts missing due to the Soviet boycott, Romania failed to match this success.

FIG World Gymnastics, vol 2, num 3,”Bela Karolyi, coach of the world champion Romanian team,”The Soviet team was in the lead after compulsories with 0.7 points in Fort Worth too. We thought and hoped we could do it again. The Soviet girls deserved their victory. Congratulations”.

Romanian journalist Gheorghe Mitroi noted for Almanahul Scanteia, 1981, that the Romanian gymnasts “lacked new and difficult elements in their routines and committed numerous errors…The team showed some regress in relation to the Olympics in Montreal or Fort Worth : less homogeneity, fewer new elements and elements of great difficulty ( which score well), instead more missed exercises”.

Elisa Estape, a gymnastics coach from Spain and Professor of gymnastics at the University of Leon not only got to see the gymnastics live in Moscow but had all the routines filmed and evaluated wrote on the Romanian floor routines in International Gymnast magazine (IG), December 1980, p.50, “The connections are weak in comparision with the Russians”.

Ursel Baer, the secretary of the British Amateur Gymnastics Association (BAGA) was a leading British judge who had officiated at the Rome, Munich and Montreal Olympics and at several World champioships. She had to evaluate all the beam routines and set their start values at this Olympics wrote in the British Gymnast, September 80, p.26, “The USSR gained a well-merited first place. They made very few mistakes in contrast to the Romanians who had a lot of bad breaks in form such as bent knees, legs apart and being flat- footed on the beam”.

In event finals in 1980 Romania won 2 gold, 1 silver and 2 bronze, the same as in Montreal. Had Eberle not fallen off beam Romania would have been the most successful team in Moscow in the event finals.

Romania won its first ever gold on floor.

Ruhn’s bronze medal on vault was Romania’s first ever Olympic medal on vault.

Romania qualified 8 gymnasts to the event finals compared to 6 at Montreal.

3 individual Romanian gymnasts won an Olympic medal compared to 2 at Montreal.

Of the 7 perfect scores awarded at the 1980 Olympics 4 went to Romanian gymnasts, 2 to Soviet gymnasts and 1 to an East German. Romania would have achieved another 2 perfect scores but for falls.

Nadia was the only gymnast to be awarded more than 1 perfect score. Her 10 score on beam in compulsories was her first perfect score on beam in a major competition since the 1977 European championships. It remains the only perfect score on beam compulsories at an Olympics. Her score of 10 on bars at the AA final was her first perfect score on bars in a major competition since the 1976 Olympics.

The unrealistic expectations after the Success in Fort Worth were fueled by Ceaucescu’s communist dictatorship. He was exerting increasing pressure on the gymnasts to win more and more medals as he believed sporting success validated his regime. But he didn’t look carefully at what had happened at the 1979 World Championships.

Rick Appleman, I.G. May 1980, p.12-13, “ The Romanians won primarily on consistency, its true. But there were 2 other factors very responsible for their success – the Russians themselves – and Nadia…Then, for the first time anyone could remember such a failure, in rapid order 3 Soviet women had disastrous errors on the uneven bars – 2 falling off…A little more of that from the Soviets wouldn’t hurt either. They obliged. The Soviet coaches ordered a watering down of beam and floor routines ; another disastrous decision…What they had done to themselves…But as they stroll the streets of Bucharest, gold medals draped around their necks, they must reflect “ Thanks Nadia – and the Soviets”

The Romanian victory over the Soviet Union in the team event was unexpected, and might not have been a victory at all if the Russians had worked Svetlana Agapova instead of their injured Natalia Shaposhnikova, who was suffering from a severely- damaged ankle. Shaposhnikova finished as only the 21st highest scoring gymnast in team optionals.

What did it mean for the 1980 Olympics? Nadia had only performed 5 routines for the team instead of the usual 8 so Romania should boost their score. They could also rely on her name to gain extra tenths.John Crumlish, IG, November 1983, in an article reviewing and praising Nadia’s carerer, noted about Fort Worth “Comaneci led the field after compulsories although observers felt the judges favoured her”. E.G. on beam Nadia scored 9.9 even though her exercise was recorded as 1 minute 11 seconds. This should have meant a 0.2 deduction for being short on time but this deduction wasn’t taken. Also the USSR had made many uncharacteristic errors which they were unlikely to do again. Instead of Natalia Tereschenko they would have Elena Davydova, a much better gymnast. So much so that before the Olympics Frank Taylor, President of the World Association of Sports Writers predicted that Davydova would win the AA gold medal.

After the Olympics The United States Olympic Committees book on the Moscow Olympics noted “The order of finish Davydova, Comaneci and Gnauck (tie), Shaposhnikova and Kim certainly accurately reflects the relative abilities of the world’s top gymnasts”.

Paul Williams, Chairman of the BAGA Men’s Technical Committee was a judge at the Men’s gymnastics in Moscow. He reviewed the women’s AA final and wrote “Davydova fully deserved her gold medal in a brilliant display of high quality work”.

Elisa Estape ” After having analysed my films i am absolutely convinced that Davydova was the proper winner in the AA final”

Ursel Baer wrote ” Davydova richly deserved to be Olympic champion”.

I forgot to add to the team results in 1980 that Cristina Grigoras was underage at the Moscow Olympics and without her scores Romania would have won the bronze medal instead of taking silver.