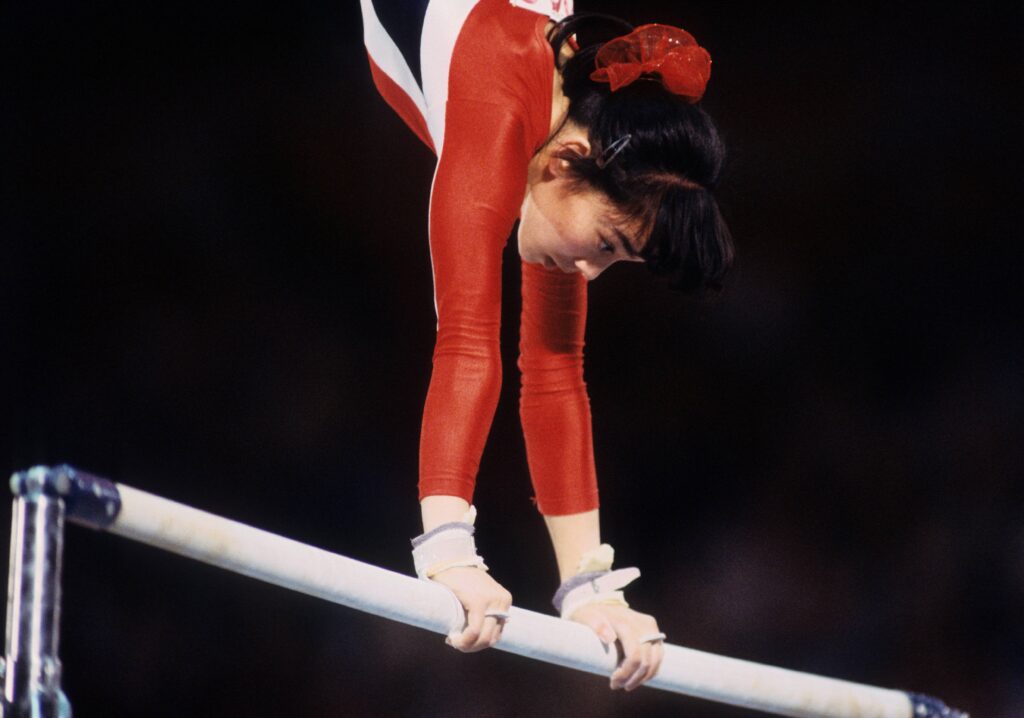

When Ma Yanhong scored 19.825 on uneven bars at the 1979 World Championships in Fort Worth, Texas, she became the first Chinese gymnast to win a world title. The moment carried weight beyond sport. It was December 1979, just months after the United States and the People’s Republic of China had established full diplomatic relations, and American spectators watched the five-star red flag rise in a Texas arena. A fifteen-year-old from the Bayi military sports team had arrived on the world stage at a pivotal moment in both gymnastics history and geopolitical realignment.

The two articles translated here—one an immediate dispatch from Xinhua News Agency filed from Fort Worth, the other a 1981 profile from the People’s Daily—show how Chinese state media framed this breakthrough. They follow familiar patterns of socialist sports journalism: diligence and endurance, sacrifice of personal comfort for collective glory, the coach’s discernment, and the athlete’s humility in victory.

At the same time, these reports preserve a vivid record of elite athletic life in late-1970s China. They describe a life of extreme (and unhealthy) discipline: cracked lips from dehydration, severely restricted food intake, and hands hardened by hundreds of repetitions of release moves. This is sports journalism in the service of a state narrative, but it is also lived reality. These accounts capture details that help us understand China’s re-emergence as a world power in women’s gymnastics.

Read closely, the articles also hint at unresolved questions. The ages they cite—fourteen at the 1978 Asian Games and fifteen in December 1979—imply a 1964 birth year. When International Gymnast interviewed her in 1999, the magazine reported her birthdate as March 21, 1964. However, at the 1984 Olympics, Ma’s official competitive date of birth was July 5, 1963. Under either birth year, Ma was age-eligible to compete at the 1979 World Championships. The puzzle, then, is not eligibility but motive: why alter her date of birth at all?

Unfortunately, the articles do not answer that question. Nonetheless, I hope that you can enjoy these articles about Ma, whose bar work, according to International Gymnast, possessed “a quality that has never been surpassed.”

For more historical context, see:

- 1973: China Travels to the United States for a Tour

- 1978: The People’s Republic of China Rejoins the FIG

A New Flower Blooms on the International Sports Stage

On December 9, at the Fort Worth Sports Arena in the United States, the Five-Star Red Flag was raised for the first time and the Chinese national anthem was played. Fifteen-year-old Chinese gymnast Ma Yanhong won the women’s uneven bars title at the 20th World Gymnastics Championships, scoring 19.825 points. This marked China’s first-ever gold medal at a World Gymnastics Championships.

The gymnast from the German Democratic Republic, Gnauck, also scored 19.825, and the two shared first place.

The women’s apparatus final was the final event of the championships. Despite ticket prices reaching 20 U.S. dollars, the arena—capable of holding more than 12,000 spectators—was completely full.

In the earlier rounds, Ma had already distinguished herself. In both the compulsory and optional team competitions, she earned outstanding scores on the uneven bars, becoming one of the most popular athletes with the audience. In the compulsory round she received a 9.95, one of only three athletes to do so—the others being Romania’s famed Nadia Comăneci and East Germany’s rising star Gnauck. In the optional round, Ma and Gnauck again tied for the highest score, 9.90 (Comăneci did not compete in that event due to a hand injury).

That evening, Ma once again scored 9.90, sharing first place with Gnauck. She executed her high-difficulty routine with exceptional quality, particularly her “clear hip to handstand with a 360-degree twist” and her “high-bar release with a 180-degree twisting tucked front somersault dismount”, both of which drew enthusiastic applause.

Ma Yanhong is a student at the Guangzhou Military Sports Institute of the People’s Liberation Army. Though young, she trains with great diligence and is highly regarded by her coaches. Quiet and reserved in daily life, she becomes energetic and confident once she mounts the uneven bars. She is meticulous about every detail, which gives her routines exceptional stability. She had already won this event at the Shanghai International Gymnastics Invitational and the Asian Games the previous year.

The atmosphere in the arena that evening was especially favorable to her. Even before the competition began, as she warmed up alongside athletes from other countries, the crowd applauded enthusiastically. During her routine, the arena fell completely silent except for the clicking of cameras. When she finished and raised her arms toward the judges, the stadium erupted into prolonged applause and cheers. Athletes, coaches, and spectators from many countries crowded around her afterward—some patting her head, others shaking her hand or kissing her cheek, many asking for photographs. This young gymnast had clearly won the admiration and affection of all present.

People wished her even greater success at the Olympic Games the following year.

Wu Jin, Xinhua News Agency, Fort Worth, December 9

Printed in the People’s Daily, December 11, 1979

She Trains Diligently as Always

— A Profile of Bayi Gymnast Ma Yanhong

This summer in Beijing has been especially stifling. Even sitting still at home, people find themselves sweating. Yet inside the gymnastics training hall, a young woman dressed in an off-white leotard is flipping tirelessly on the uneven bars, beads of sweat dripping to the floor and soaking through her clothes. That young woman is the well-known world uneven bars champion Ma Yanhong.

In 1978, at the age of fourteen, she competed in the Asian Games for the first time and won the uneven bars title. In 1979, at the 20th World Gymnastics Championships held in Fort Worth, USA, she again captured the uneven bars gold medal, scoring 19.825 points.

Ma Yanhong brought honor to her country. Letters of congratulations poured in from all directions. But she treated these honors as motivation to work even harder. She trained with the goal of achieving even better results at the 21st World Gymnastics Championships, to be held in Moscow that November.

“Diligent, conscientious, and tenacious” — these six characters are often used to describe Ma Yanhong’s training style. Indeed, for a top gymnast, physical conditioning, leg strength, and flexibility are fundamental requirements.

In 1975, when coach Chen Xueyao of the Bayi gymnastics team visited the Shichahai Youth Sports School to select athletes, he evaluated five candidates. Ma Yanhong was actually the weakest among them, especially in leg strength — a critical factor in women’s gymnastics, where three of the four events rely heavily on leg power. However, after watching her performance and hearing reports from her youth coaches, Coach Chen recognized her humility, perseverance, and calm mindset, and decided to select her.

Thus, at just 11 years old, Ma Yanhong entered the Bayi gymnastics team.

After joining the Bayi team, Ma Yanhong held herself to strict standards in every aspect and trained with exceptional rigor. While practicing the high-difficulty uneven bars skill known as the “straight-body release and regrasp”, she would often repeat the movement dozens—sometimes hundreds—of times in a single session. Her slender hands were worn raw, healed, and then worn raw again, gradually forming thick calluses. From repeatedly rebounding off the bar, her waist, abdomen, and legs were bruised and bloodied; when sweat ran over the wounds, the stinging pain was intense. Over time, the pale skin of these areas gradually darkened to a grayish brown.

An outstanding gymnast must not only endure hardship in training but also in daily life. Even eating required discipline. For the sake of performance, gymnasts often had to strictly control their diet. Sometimes her lips cracked from thirst, yet she could not drink freely. One Sunday, when she went home to visit her mother, her mother—knowing how much she loved fried eggs—prepared a full bowl for her. But in order to control her weight, Ma only picked up half an egg and tasted it.

Ma Yanhong’s courage in training was astonishing. Coach Zhou Jichuan, considering her physical characteristics, choreographed two high-difficulty skills for her on the uneven bars: a “clear hip to handstand with a 360-degree turn” and a “straight-bar 180-degree twisting front somersault dismount.” These were entirely new elements in women’s gymnastics at the time. Any slight mistake could result in a serious fall. Yet Ma never shrank back from difficulty. Once during practice, she nearly plunged headfirst to the ground while dismounting. Coach Zhou caught her just in time, and both were drenched in cold sweat. After a brief rest, she mounted the bar again and continued practicing until she mastered the skill.

Hardship tests a person, but honor tests a person even more. Ma Yanhong remained diligent and grounded, training conscientiously and maintaining a modest, hardworking attitude.

In modern gymnastics, those who dare to innovate are the ones who succeed. We believe that Ma Yanhong will achieve even greater results at the World Gymnastics Championships.

— Wang Hua

The People’s Daily, August 16, 1981

Appendix: More on Ma’s Age

If you’d like to take a deeper look at Ma’s age and career, the following articles may be useful. Based on the earliest Chinese reporting, 1964 is the only birth year that aligns consistently with her competitive record.

1978: 14 at the Asian Games

Young Swallows Greet the Rising Sun

—On the Women’s Artistic Gymnastics Team Competition at the 8th Asian GamesOn the afternoon of December 10, the First Gymnasium of the Bangkok National Sports Center was a sea of excitement. Cheers and applause surged continuously, spilling out beyond the arena. Though the gymnasium had only 4,000 seats, more than 6,000 spectators packed inside; even the areas around the competition floor were filled with standing crowds. Staff were forced to block the steady stream of incoming spectators with rows of chairs.

According to a December 11 report in Thailand’s Sing Siam Daily, enthusiasm for the gymnastics competition—particularly because Chinese women gymnasts were competing—was even higher than in previous days: “Tickets were snapped up in an instant, leaving thousands to sigh in frustration outside the gates.” Indeed, under the trees outside the arena, several television tents had been set up, each surrounded by hundreds of spectators sitting on the ground, breathing in rhythm with the competition inside.

At 4:30 p.m., the second group of the women’s team competition began. The Chinese athletes, dressed in vermilion-red uniforms, strode briskly onto the floor, entering first. They were followed by competitors from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Japan, and South Korea. The arena instantly came alive—some spectators applauded, others waved, warmly welcoming the athletes.

The Chinese team consisted of He Xiumin, Zhu Zheng, Liu Yajun, Ma Yanhong, Wang Ping, and Ma Wenju. Their average age was under seventeen. The first apparatus for the Chinese team was vault. All six gymnasts competed calmly and confidently, their movements vigorous and heroic. One after another, they soared into the air with fast run-ups, timely hand pushes and shoulder blocks, and clean, precise twists in flight. Every gymnast scored above 9.30. Under the scoring rules, their team total for vault was 47.55.

The second event was the uneven bars. Sixteen-year-old Wang Ping, well-proportioned in build, competed first. After dusting her hands with chalk and saluting the judges, she sprinted forward and leapt to grasp the high bar in one fluid motion. Like a young swallow darting up and down, she flew through her routine with innovative composition and precise, polished execution. The applause grew louder with each movement, and the judges awarded her a 9.60.

Seventeen-year-old Liu Yajun followed with a straddle vault onto the bars, a supported straddle backswing to handstand, and a stretched back salto dismount from the high bar. The routine was difficult, the landing steady, earning her 9.70. He Xiumin and Zhu Zheng, performing routines of equal difficulty and refinement, each received scores of 9.80. Their dismounts—such as the tucked back salto with a full 360-degree twist, and the belly bounce from low bar to straddled flight over the high bar with a 180-degree turn—were moves not seen at the recent World Gymnastics Championships in France.

Fourteen-year-old Ma Yanhong, the uneven bars champion at this year’s Shanghai International Gymnastics Friendship Invitational, scored an impressive 9.95. She was clearly challenging the summit of world gymnastics, striving to embody the originality, daring, and mastery demanded by modern competitive gymnastics. Her skills—such as a clear hip circle with a full 360-degree turn to handstand, flowing into a reverse grip hang on the high bar—were world-class in difficulty. Her final dismount, a stretched high-bar release with a 180-degree turn into a tucked front salto, was like a young swallow diving swiftly from the sky—beautiful in form and utterly captivating. When the high score flashed on the scoreboard, the entire arena erupted in jubilation. She was the highest single-event scorer of the gymnastics competitions over the two days.

Floor exercise was the Chinese team’s final event. To the bright, rhythmic strains of piano music, the Chinese gymnasts sprang into the air, spun rapidly, and interwove elegant, passionate dance movements with their technical elements. The performance was captivating, and applause rose in wave after wave. Known for her difficulty, Ma Wenju opened with a tucked double back salto with a full twist and closed her routine with another double back salto, earning 9.70.

When the competition concluded, the Chinese women’s gymnastics team claimed the team gold medal. He Xiumin won the individual all-around title, while Liu Yajun and Zhu Zheng tied for second place.

At 7:30 that evening, inside the Bangkok National Sports Center gymnastics hall, the five-star red flag was raised slowly to the stirring strains of the Chinese national anthem. Dressed in white competition uniforms, the Chinese gymnasts stood atop the podium, waving to the thousands of cheering spectators. Their gestures conveyed not only the joy of victory, but—more importantly—the determination to press forward bravely along a long road of learning and the bright promise of the future ahead.

Xinhua News Agency reporters: Guo Jing, Li Hepu

The People’s Daily, December 13, 1978

1979: Turned 15 in March

Concerning the Bangkok meet we should still mention that the highest score at all was awarded to Ma Yen-hung, who became 15 in March. She was given 9.90 on the uneven bars and missed third place only because of a messed-up optional exercise on the Floor (9.00). On the uneven bars, she had done brilliantly already at the International of Shanghai and there she had been at a draw with Nadia Comaneci, 9.90 as well! We would like to know the top elements in her optionals.

Josef Göhler’s International Report in International Gymnast, May 1979

1981: 17 at the Tokyo Broadcasting System Cup

At the 12th Tokyo Broadcasting System Cup International Gymnastics Invitational

Chinese Gymnasts Win Four Gold Medals

Xinhua News Agency, Tokyo, April 25 —

Chinese gymnasts Ma Yanhong, Wen Jia, and Huang Yubin displayed a courageous, tenacious, and victory-seeking spirit this afternoon at the 12th Tokyo Broadcasting System Cup International Gymnastics Invitational, held at Yoyogi National Gymnasium (Second Gymnasium). Competing in ten men’s and women’s apparatus events, they won a total of four gold medals, two silver medals, and three bronze medals.Seventeen-year-old Ma Yanhong captivated the entire arena in the uneven bars competition with a routine of exceptionally high difficulty. Her skills—including a jump to handstand with a full 360-degree turn back to handstand, and a stretched bar swing into a back salto with a 360-degree twisting dismount—were executed compactly and cleanly, drawing enthusiastic cheers from the crowd. When the electronic scoreboard displayed a score of 9.9, the arena erupted in thunderous applause. Ma Yanhong also captured first place on balance beam with a score of 9.8.

Seventeen-year-old Wen Jia won first place in women’s floor exercise with a score of 9.6. In the men’s competition, Huang Yubin took first place on still rings, scoring 9.65.

The invitational was hosted by the Japan Gymnastics Association. A total of 22 male and female gymnasts from Japan, China, and the United States participated. No team or all-around titles were awarded; the competition consisted solely of individual apparatus events.Japanese gymnasts demonstrated formidable strength, winning six gold medals, four silver medals, and five bronze medals. In particular, Japanese athletes claimed nearly all of the top three positions in both the men’s parallel bars and horizontal bar events. The American competitors earned six silver medals and one bronze medal.

The People’s Daily, April 26, 1981

2000: 36 in March

Catching up with Ma Yanhong: Remaining True to Form

Twenty-one years after she won China’s first world championship title, uneven bars legend Ma Yanhong still plays an inspirational role in her homeland as a multi-faceted entrepreneur whose achievements have transcended gymnastics fame.

Now proprietor of a Japanese restaurant in Beijing, Ma has also succeeded as a sports promoter (i.e., organizing and finding sponsors for a marathon), coach and television commentator. “I try to have a fulfilling life,” understated Ma from the broadcast booth during a brief break at last October’s worlds in Tianjin, China.

Ma, who will turn 36 on March 21, downplays the significance of her resume. A steady stream of adoring fans lined up for her autograph throughout the worlds, although Ma insists her face and notoriety are rarely linked. “Most people in China remember my name, but when they see me, they don’t know who I am until they hear the name,” she notes.

Recognizable or not, Ma is remembered for her impeccable form, swing technique and still “E”-rated dismount on the bars (hip circle, hecht to tucked back salto with full twist). Validated by numerous international titles, Ma is assured an indelible place of reverence in Chinese sports annals.

At the ’79 Fort Worth worlds—China’s first—she shared the gold medal on bars with Maxi Gnauck of the German Democratic Republic. Ma reinforced that quickly-earned reputation two years later at the Moscow worlds, where she finished second to Gnauck on her specialty. There, perhaps Ma’s more impressive feat was placing fourth all-around behind three Soviets on their home turf. (China boycotted the ’80 Olympics, also held in Moscow.) Ma rose to the ultimate occasion at the ’84 Olympics in Los Angeles, where she tied for the uneven bars gold with American Julianne McNamara (both gymnasts scoring 10.0 in finals) and placed sixth all-around.

Ma says her pursuit of technical perfection was a secret incentive instilled in 1976, when she viewed videos of Romanian Nadia Comaneci and the Soviets performing at the Montreal Olympics. “I had a goal to be the best on bars, and when I saw the tapes, I saw that I could be as good as they were, or better,” recalls Ma.

Rather than seek the stardom that would find her three years later, Ma instead prepared with quiet diligence. “I had confidence that I could be better than [the ’76 Olympians], but I didn’t tell anyone,” says the once-married but now single Ma. “I really worked my way up. I always had the goal in my heart to compete with them and let everyone know that China could be better at something.”

Ma considers her landmark ’79 worlds gold to be her most cherished feat, since it ushered China to instant powerhouse status in the sport. But she expresses slight consternation when placing her innovations in perspective to current trends. “Gymnastics is much more difficult today because the improved equipment has helped the gymnasts do much harder moves, but form is not as beautiful as before,” Ma says.

Known as much for her impossibly straight handstands and pointed toes as for her daring pirouette and aerial moves, Ma cites shifted priorities for coaches and gymnasts since her training days. “When I did gymnastics, it wasn’t that hard, so we had to pay attention to how the moves looked, how to make them more perfect,” says Ma passionately. “My coach always said you should not just be able to do an element, but also do it perfectly. I always kept that in mind and always tried to be perfect.”

Today’s uneven bars routines often agitate her because (unlike the sets she performed) she believes the difficulty is out of proportion to the quality. “When I watch bars now, my heart jumps,” Ma says. “There are so many difficult moves, but after them, simple moves which don’t look good. It’s a pity. I wish they would do the whole routine as perfectly as they do the difficult skills.”

She is also critical of what she deems a monotonous direction in which the current Code of Points compels gymnasts on beam and floor. “A lot of gymnasts do similar tumbling and combinations because of the requirements, so the routines look like compulsories,” she laments. “I don’t think this helps develop variety, or helps gymnasts create something new.”

Although other pursuits have left Ma no time to implement a return to orgiinality recently, she did enjoy a three-year stint at the SCATS club in California from 1990-93. There, known affectionately as “Amy Ma,” she trained aspiring gymnasts such as Jeanette Antonlin, whom Ma proudly watched compete for the U.S. in Tianjin.

Ma’s professional non-gymnastics agenda is frenetic and loaded, but her still-esteemed personal example of immaculate gymnastics offers a timeless directive. “I would hope that coaches realize it’s not enough for their gymnasts to learn difficult moves, but also with good form,” she says.

Precise and motivated as always, Ma is staying true to form herself.

—John Crumlish, International Gymnast, January 2000

More Interviews and Profiles