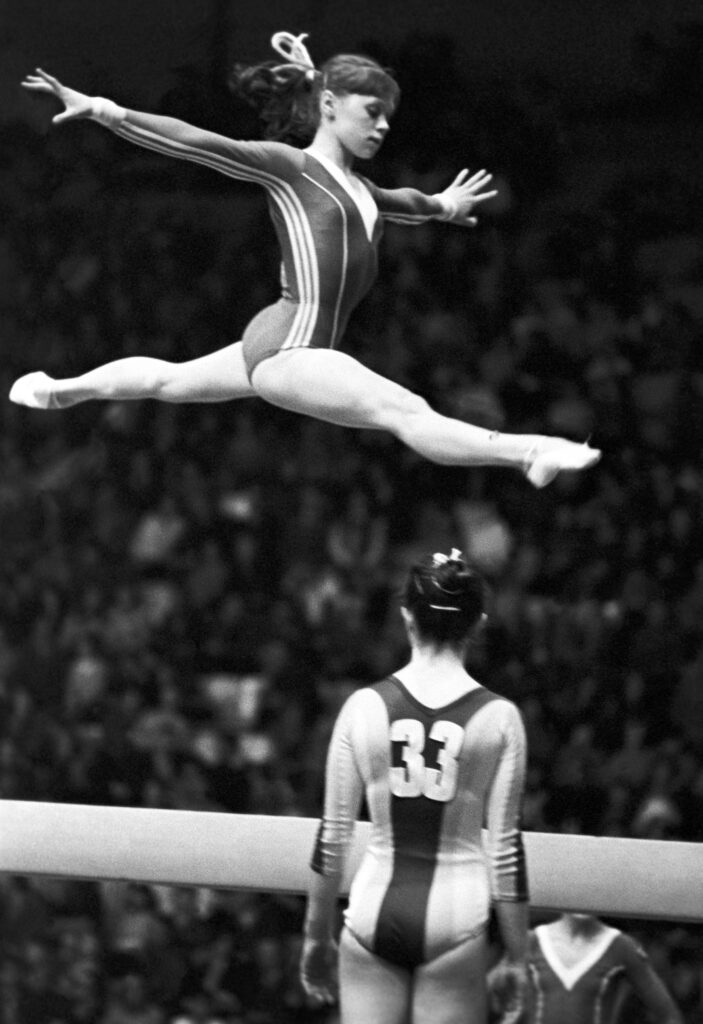

At the 1984 Friendship Games, Olga Mostepanova was untouchable. Her perfect 40.00 in the all-around was a triumph of grace, control, and artistry. But just one year later, on the world’s biggest stage, her story took a different turn. At the 1985 World Championships, she faltered on beam during the team optionals.

On balance beam, Olya Mostepanova wobbled badly, as if a powerful gust of wind had burst through the glass doors of the velodrome. What an effort it took for Olya to stay on, not to jump down onto the blue springy mats! By the way, this is precisely an expression of willpower—of courage, if you like. Her deductions were smaller (9.625), yet given the current closeness of the results, Mostepanova slipped two steps back on the tournament ladder, landing in third…

And so now, on our team, there had to be a gymnast who could draw close to the Romanian Ecaterina Szabo, who was breaking away. The burden of leadership was taken on by Yurchenko, the team captain.

Mostepanova was bandaging her leg, waiting for the score to appear on the board. She saw it, pursed her thin lips in frustration. Yurchenko, too, was upset for her teammate and quietly said: “Hold on, Olya.” And the 9.9 that Natasha received on the beam was like a challenge—it was excellent. Away with doubts, away with sadness—the team victory awaited us!

Sovetsky Sport, no. 259, 1985

На бревне сильно зашатало Олю Мостепанову, как будто мощная струя ветра прорвалась сквозь стеклянные двери велодрома. Каких усилий стоило Оле устоять, не спрыгнуть на голубые пружинящие маты! Между прочим, это и есть проявление воли, если хотите — мужества. Сбавки были у неё поменьше (9,625), однако при нынешней плотности результатов Мостепанова сделала два шага назад по турнирной лестенке — она стала третьей…

И вот теперь в нашей команде должна была найтись гимнастка, которая смогла бы вплотную приблизиться к уходящей в отрыв румынке Екатерине Сабо. Бремя лидерства взяла на себя Юрченко, капитан сборной.

Мостепанова бинтовала ногу, ждала оценки на табло. Увидела, поджала от обиды тонкие губы. Юрченко тоже огорчилась за подругу, тихо сказала: «Держись, Оля». И 9,9, полученные Наташей на бревне, были как вызов, это было здорово. Прочь сомнения, прочь грусть — нас ждёт командная победа!

Your annual reminder that the skill should not be called an Ónodi on beam.

Though she qualified for the all-around finals, Mostepanova never appeared there, sidelined with an ankle injury. At least, that was the official story at the time.

Experts in our sport will probably be surprised to learn that, in the final, it was not Olya Mostepanova and Irina Baraskanova, who had placed third and fourth respectively, but Oksana Omelianchik and Yelena Shushunova, who had been in sixth and seventh. Because of injuries, the coaches replaced them.

Sovetsky Sport, no. 260, 1985

Знатоки нашего вида, наверное, удивятся, узнав, что в финале от нашей страны выступали не Оля Мостепанова и не Ирина Барасканова, которые занимали соответственно третье и четвертое места, а Оксана Омельянчик и Елена Шушунова, которые были на шестой и седьмой позициях. Из-за травм тренеры их заменили.

But in retrospect, the story was less straightforward. By 1989, Mostepanova didn’t parrot the official story by citing injuries. Instead, she suggested that the Soviets had made a strategic substitution, hoping to topple Romania’s Ecaterina Szabo in the all-around. And that substitution wounded her.

What follows is an interview with Mostepanova from 1989. No longer the golden idol who once received bags of fan mail, she was instead quietly shaping the next generation of gymnasts at Dynamo. This conversation traces her evolution—from the fragile, ethereal star of Olomouc to the patient mentor of Moscow—revealing the resilience that carried her through injury, politics, and heartbreak, and the warmth that still makes her unforgettable, whether on the competition floor or in the gym.