These three People’s Daily articles, spanning fourteen years from 1981 to 1995, trace the arc of Li Ning’s transformation from teenage gymnastics prodigy to business entrepreneur. Read together, they chart not only an individual career but a broader shift in Chinese sport and society, as the values and constraints of Mao-era athletic culture gradually gave way to new possibilities.

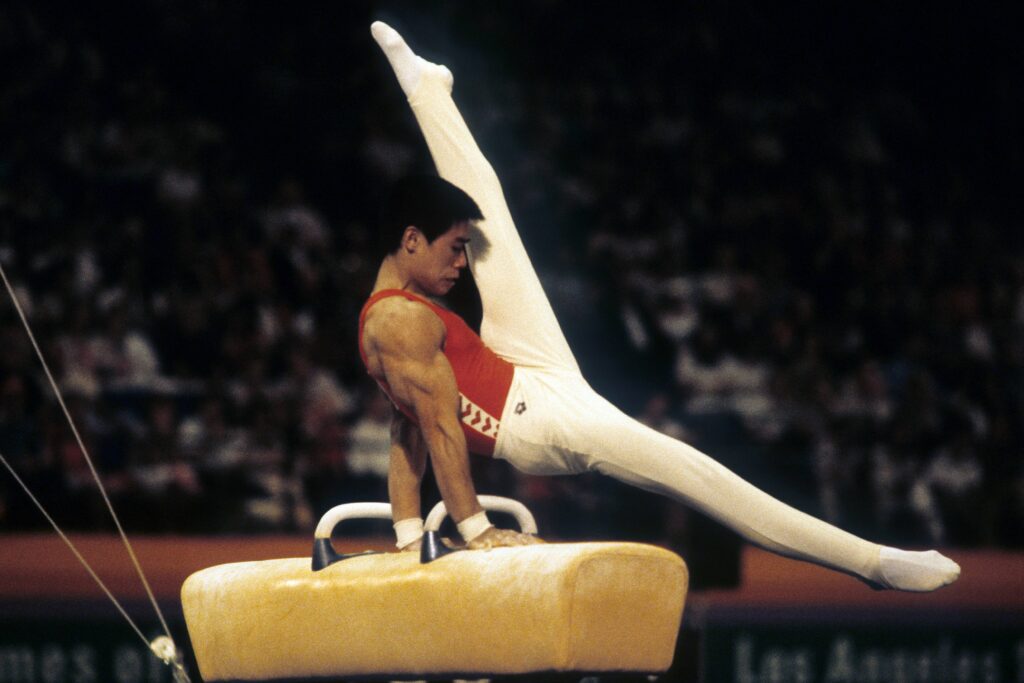

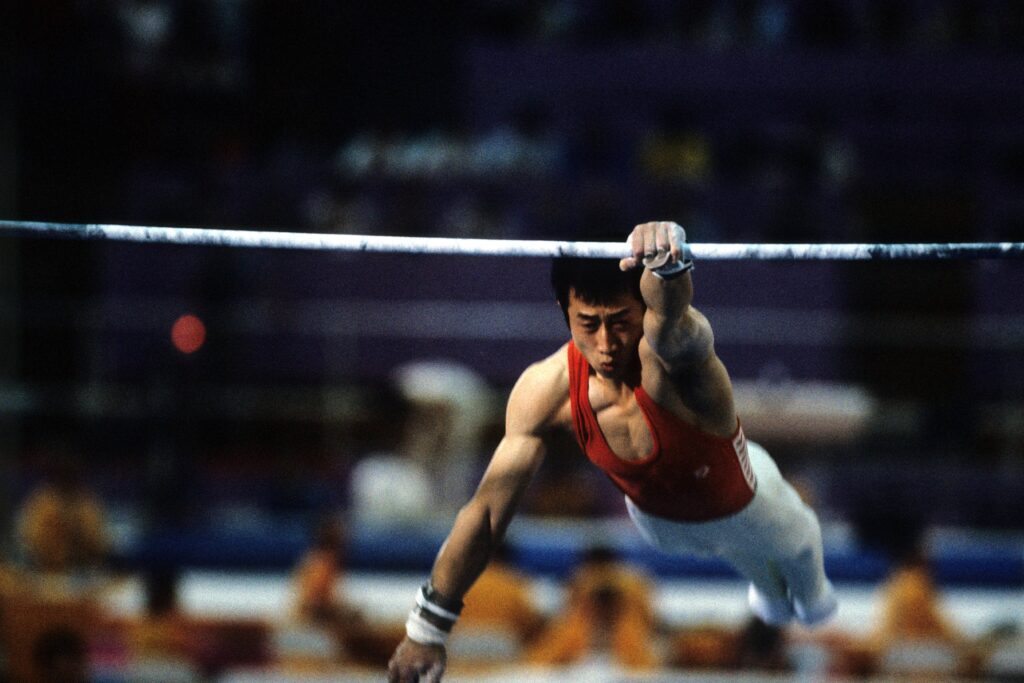

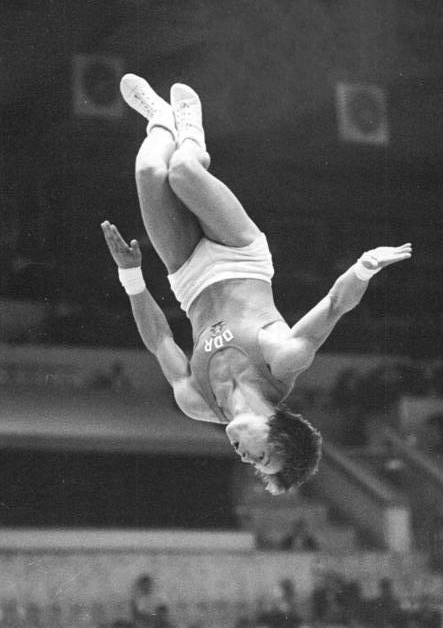

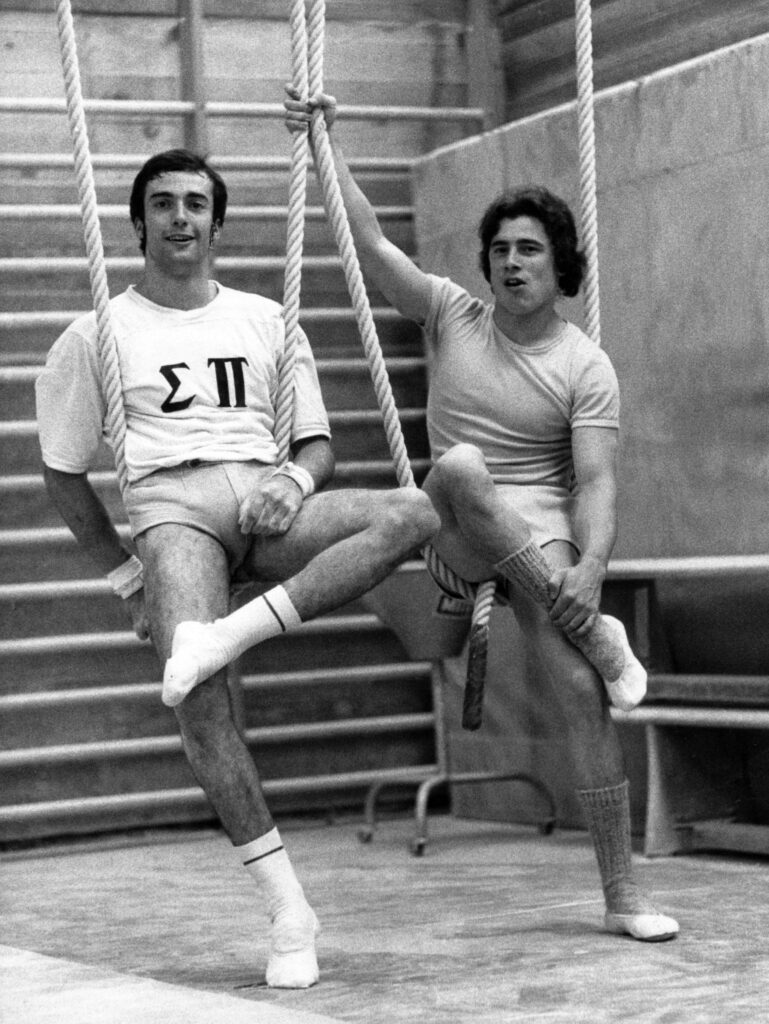

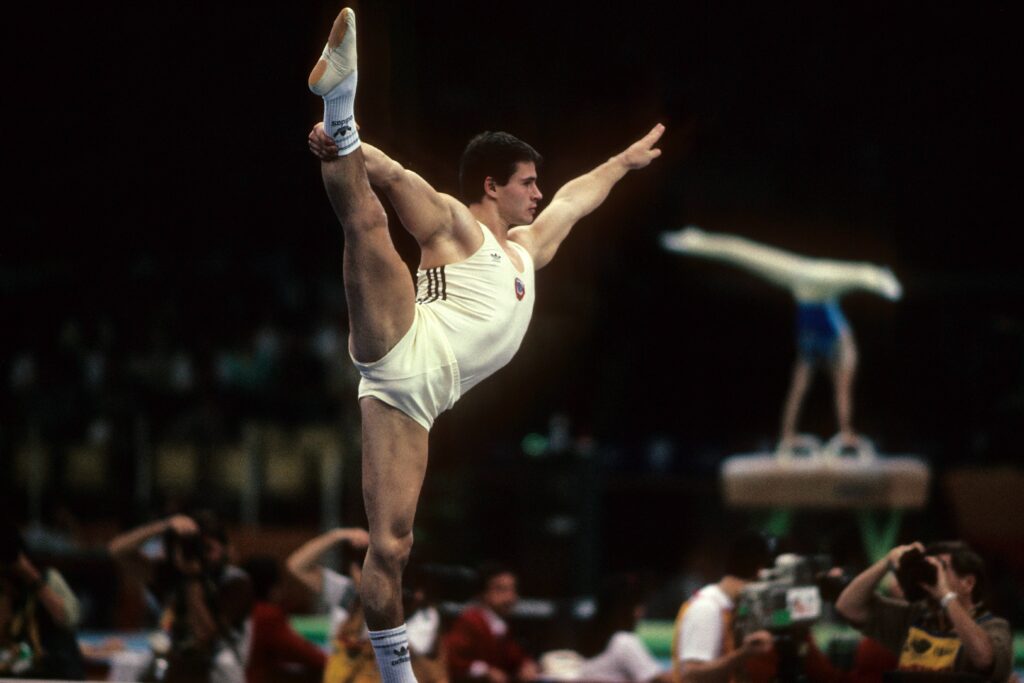

The first piece, published on August 30, 1981, introduces Li Ning at eighteen as a rising talent who had just won China’s first gold medal at the World University Games in Bucharest. Its narrative structure would become familiar in Chinese sports journalism: early discovery, setbacks overcome through ideological commitment, and moral guidance from exemplary teammates—in this case, Tong Fei. Li Ning appears here as a product of the state sports system at its ideological peak, his achievements framed primarily in terms of collective honor, discipline, and service to the nation rather than personal advancement.

By the end of the 1980s, both Li Ning’s career and China itself were entering a period of profound transition. Following the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, Deng Xiaoping initiated a series of economic reforms that gradually loosened the rigid command economy of the Mao years. Limited private enterprise and selective engagement with foreign capital were introduced, even as Communist Party control remained firmly in place. In the early 1980s, these reforms were tentative and uneven; by the early 1990s, they had begun to reshape everyday life, labor, and ambition, including elite sport.

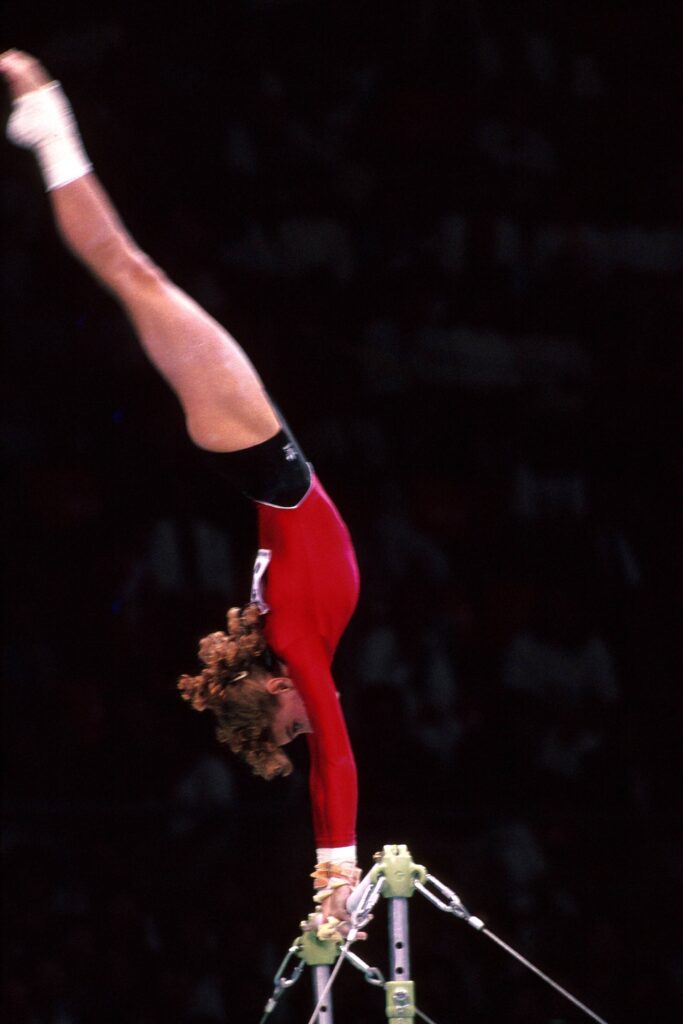

It is against this backdrop that the second article, published in October 1990, finds Li Ning navigating unfamiliar terrain. Retired from gymnastics, he had joined Jianlibao, a state-owned sports drink manufacturer, to help develop China’s first indigenous sportswear brand. The piece reveals an athlete unsettled by the indignity of competing in foreign-branded clothing and determined to create a Chinese alternative. In a familiar literary trope about emerging markets, we witness Li Ning trying to cut across time and space in impossible ways. The writer even suggests that, for the retired gymnast, time itself has become three-dimensional.

The final piece, from March 1995, is an obituary for Li Ning’s mother. Qin Zhenmei, who died of cancer at fifty-four, is presented as the archetype of the self-sacrificing Chinese mother—a mother who went to great lengths to sew her son a training uniform and who promoted her son’s clothing brand from her deathbed. Yet the article is equally structured around Li Ning’s confession of filial failure—his admission that years of relentless work left him scarcely present at her bedside, sharing only three meals with her in her final year. Here, personal loss and moral regret serve to place commercial success within an acceptable moral framework, ensuring that entrepreneurial achievement does not appear to override traditional obligations.

Enjoy this longitudinal view of Li Ning’s biography, as refracted through the People’s Daily.