In preparation for the 2021 Tokyo Olympics, let’s look back at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, starting with the women’s competition.

This is a long post, so here are some links to help you jump around.

Historical Context | Gymnastics Context | Judging Context | Judging Assignments | Video Footage | Team Competition | All-Around | Event Finals | The End of an Era

Compulsories: Monday, October 19

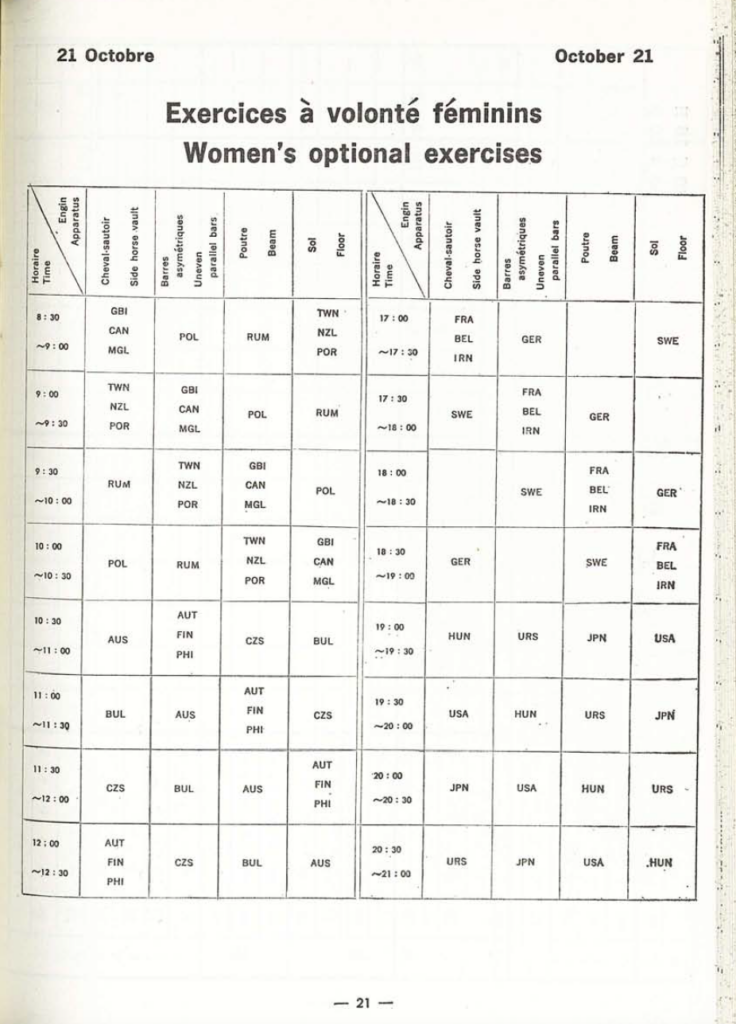

Optionals: Wednesday, October 21

Event Finals: Thursday, October 22; Friday, October 23

Number of Female Athletes: 83

Youngest Gymnast: Jamileh Sorouri (14, IRI)

Oldest Gymnast: Rayna Grigorova (33, BUL)

Type of Equipment: Nissen-Senoh

Note: Jamileh Sorouri is the first (and only so far) female gymnast to represent Iran at the Olympics.

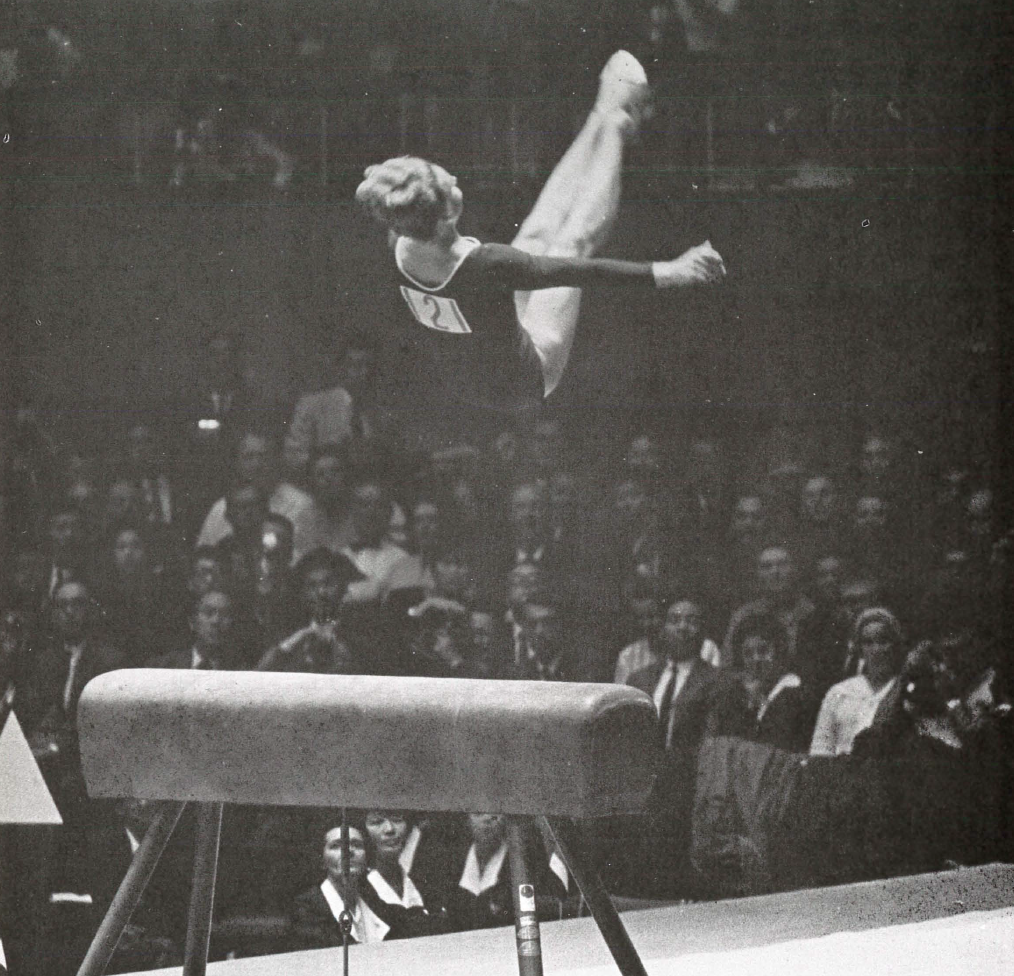

Photo: Larisa Latynina, Modern Gymnast, Jan. 1965

Historical Context

Gymnastics doesn’t happen in a vacuum. So, here’s some information to get you situated.

- Austria

- The Winter Olympics were held in Innsbruck, Austria.

- The 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, Norway were the first Winter Olympics to be held in a different year from the Summer Olympics.

- Soviet Union

- Just before the start of the gymnastics competition, on October 14, 1964, Nikita Khrushchev was stripped of his power.

- He was replaced by Leonid Brezhnev.

- Czechoslovakia

- On July 11, 1960, the National Assembly approved a new Czechoslovak constitution, declaring ecstatically, “Socialism has triumphed in our country!”

- By September of 1964, the government moved from a rigid state-owned command economy to a mixed economy.

- Japan

- Japan was on a growth trajectory. In 1960, Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda challenged the country to double its income in the next decade.

- The Shinkansen, a high-speed rail system between Tokyo and Osaka, was inaugurated on October 1, 1964, just in time for the Olympics.

- Germany

- In 1961, the Berlin Wall was constructed, separating East and West Germany.

- Nevertheless, the two Germanies competed together at the Tokyo Olympics.

- United States

- President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, sex, color, religion, or national origin.

- Surgeon General Luther Terry reported that smoking might be hazardous to one’s health. (There was an article about the dangers of smoking in Modern Gymnast.)

- The Vietnam War and Cold War raged on.

Not your type of history? No problem. Here is some more information.

- Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory was published.

- The Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand” was the number one song.

- The Ford Mustang was officially unveiled to the public.

Gymnastics Context

Here’s what was happening in the world of gymnastics…

- The Soviet Union had won the Olympic title in 1960 and World title in 1962.

- Larisa Latynina was the reigning World and Olympic all-around champion.

- But, but, but: She proved beatable. In a dual meet between the USSR and Sweden in April of 1964 (Modern Gymnast, May/June), Latynina finished fourth (76.80) in the all-around.

- Elena Volchetskaya (77.00), Polina Astakhova (76.95), and Tamara Manina (76.90) beat her.

- The Eastern Bloc withdrew from the 1963 European Championships. This included Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and the USSR.

- During the Tokyo Internationl Sports Week (Pre-Olympics Test Event), Latynina won the all-around. Sofia Muratova was second, and Čáslavská was third (Yomiuri, Oct. 16, 1964).

- The People’s Republic of China did not participate in the 1964 Olympic Games because of the IOC’s recognition of the Republic of China (Taiwan). (You can read the official statement from the Chinese Gymnastics Association here.)

- The first international course for judges was held in Zurich after the 43rd Congress. 12 brevet judges were certified for the women. (53 were certified for the men.)

Need to refresh your memory about what happened at the 1962 World Championships? No problem. Here’s a quick recap.

Judging Context

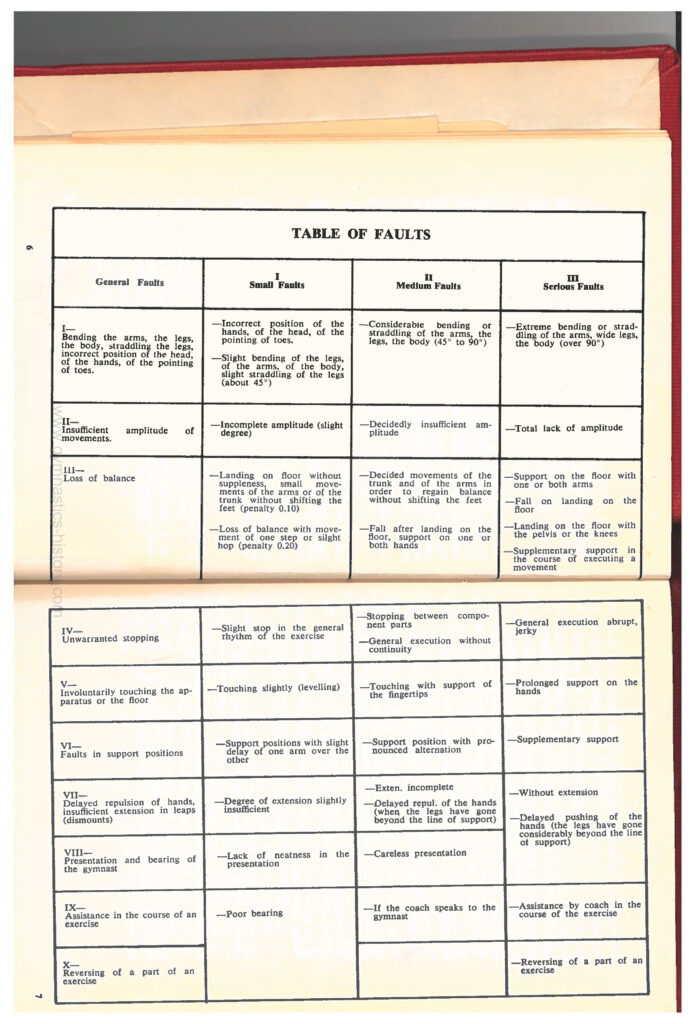

You can read the 1964 Code of Points in its entirety here. Otherwise, here are some of the rules…

During optionals, team members could not perform the same mounts or dismounts. This created problems for Team USA:

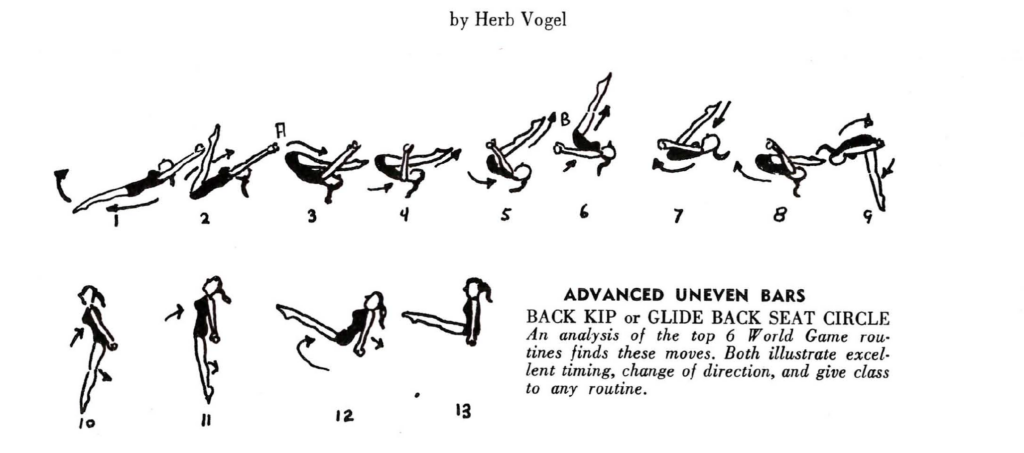

- Problem #1: Four of the seven U.S. gymnasts had a reverse kip mount on uneven bars, which meant three gymnasts needed to learn new mounts. (Not sure what a reverse kip was? See below.)

- Problem #2: The same thing happened on beam. Two gymnasts had the same forward roll mount, and two gymnasts had the same run-on mount.

- My thought bubble: Undoubtedly, this rule favored teams with a centralized training strategy.

There were five judges on each apparatus. High and low scores were dropped. The remaining 3 scores were averaged.

- Note: This is different from the men, who had four judges (plus a superior judge overseeing things), dropped the high and low scores, and averaged the two remaining scores.

The breakdown of the 10.0:

- 3 points for difficulty (3.4 for the men)

- 2 points for the combination (1.6 for the men)

- 5 points for execution and overall impression

- Note: Performing extra difficulty was actively discouraged on the women’s side.

- From the Code: “For the sake of general beauty of movement, and in order to avoid any regrettable excesses, it is expressly recommended not to exceed this level.”

Side note: There was a belief that the four events were designed for women’s bodies. “The four Olympic events are specifically designed to fill the special physical needs of girls” (Modern Gymnast, March 1964).

Here are a few execution deductions.

Judging Assignments

Vault

- Kobayashi (JPN)

- Stroescu (ROM)

- Riedelberger (GER)

- Slizoloska (POL)

- Gable (USA)

- Responsible: Sepa (YUG)

Uneven Bars

- Ljunggren (SWE)

- Kovács (HUN)

- Aizawa (JPN)

- Ponnertová (TCH)

- Hugon (FRA)

- Responsible: Demidenko (URS)

Balance Beam

- Rakoczy (POL)

- Tintěrová (TCH)

- Gorokhovskja (URS)

- Buzea (ROM)

- Caelli (AUS)

- Responsible: Nagy-Herpich (HUN)

- Timer: Matsuzaki (JPN)

Floor

- Weisenberger (AUT)

- Cheffer (URS)

- Bartha (HUN)

- Gulack (USA)

- Ewald (GER)

- Responsible: Gotta (ITA)

- Timer: Onuki (JPN)

- Line Judge: Okamoto (JPN)

- Line Judge: Miyashita (JPN)

Official Report: The Games of the XVIII Olympiad, Tokyo

Video Footage

Unfortunately, the video doesn’t include a lower third with the gymnasts’ names. (Though, the commentator does mention the majority of the gymnasts’ names.) So, here’s a quick key to get you started.

Compulsories

- 0:00: Gerola Lindahl, SWE, BB, 8.966

- 1:39: Anna Lundqvist, SWE, BB 9.100

- 2:59: Larisa Latynina, URS, FX, 9.666

- 4:34: Polina Astakhova, URS, FX, 9.700

- 6:13: Aihara Toshiko, JPN, UB, 9.466

- 7:13: Ikeda Keiko, JPN, UB, 9.466

- 8:01: Adolfína Tkačíková, TCH, FX, 9.333

- 10:14: Hana Růžičková, TCH, FX, 9.400

- 12:14: Věra Čáslavská, TCH, FX, 9.500

Optionals

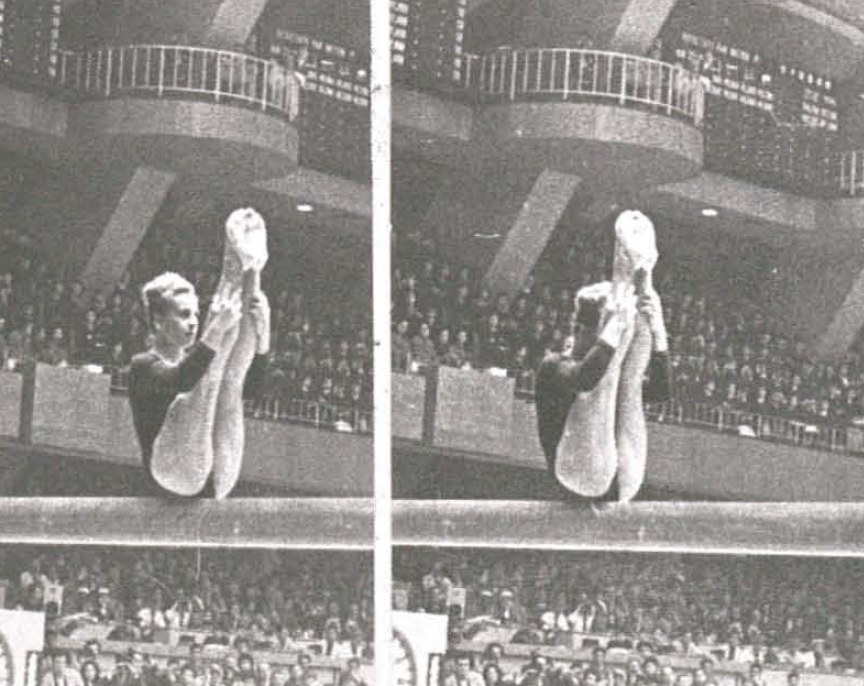

- 14:32: Hana Růžičková, TCH, BB, 9.766

- 16:40: Věra Čáslavská, TCH, BB, 9.800

- 19:11: Janice Bedford, AUS, UB, 8.133

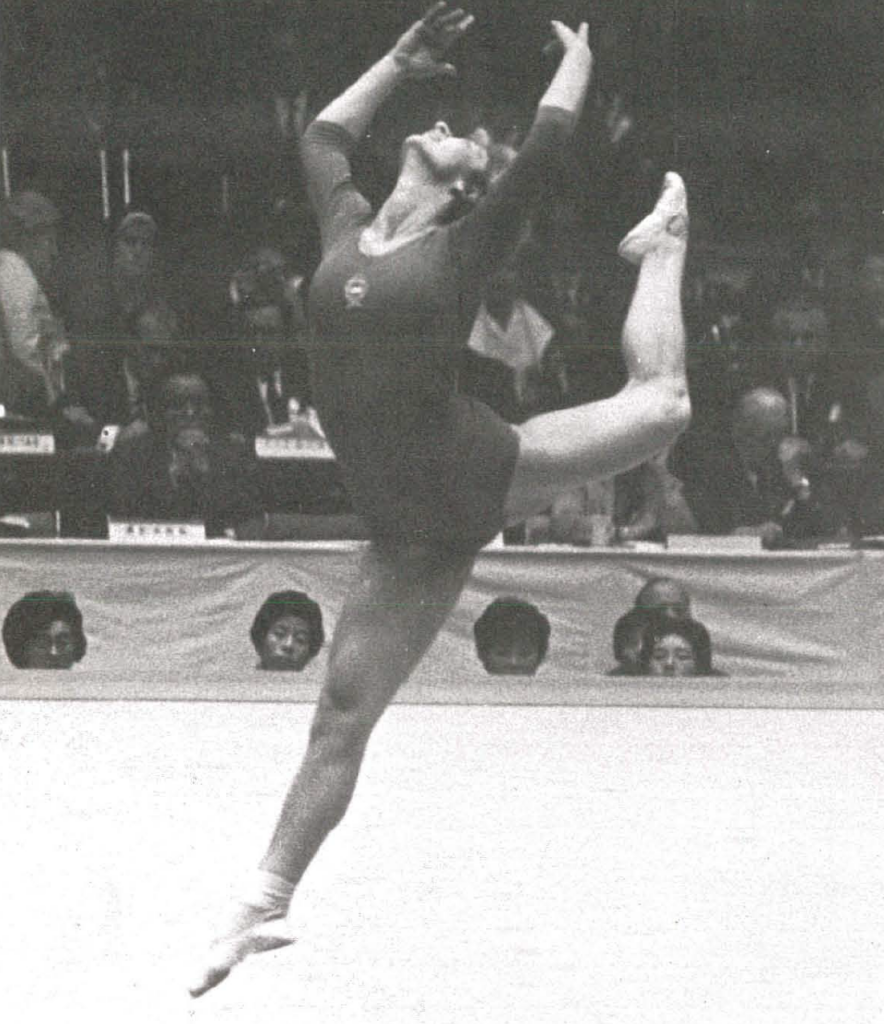

- 20:48: Věra Čáslavská, TCH, FX, 9.766

- 23:59: Tsuji Hiroko, JPN, VT, 9.333

- 30:14: Elena Volchetskaya, URS, FX, 9.500

- 31:46: Ono Kiyoko, JPN, VT, 9.466

- 33:30: Ikeda Keiko, JPN, VT, 9.533

- 36:01: Polina Astakhova, URS, FX, 9.700

- 38:12: Aihara Toshiko, JPN, VT, 9.600

- 39:16: Larisa Latynina, URS, FX, 9.800

- 42:37: Chiba Ginko, JPN, VT, 9.500

A Few Remarks on the Compulsory Footage

Ever-changing routines: At the time, compulsories changed for every major meet. The 1964 Tokyo compulsories were different from the 1962 Prague compulsories. So, you didn’t have much time to perfect them.

???: Read the following description from the compulsory beam text. Try to imagine how those words would translate into movement. And then watch the opening sequence across the beam in the footage above (0:20 and 1:52).

3. Straighten yourself on tip toes very close together, left in front, by raising the arms from bottom to top, then lower them laterally, the palms downward.

4. One step on right foot, bring left foot behind the right one, with impulse thrust right leg extended forward, land on right foot, left leg bent behind right leg, knee to the outside, simultaneously circling of right arm laterally in front of the body, in figure eight, palm upward in returning the left arm rounded in front of the body during the jump.

5. One step on left foot, bring right foot behind the left one, with impulse thrust left leg forward to land on left foot, the right leg bent behind the left leg, knee to the outside, arms lateral.

Did your imagined routine match up with the performed routine? Mine sure didn’t. Can you see why compulsories were so hard?

Scoring: Three of the Swedish gymnasts received a 9.100 on the compulsory beam routine. The other three scored 8.966, 9.000, 9.066. That raises some eyebrows 🤔 and some questions:

- Did the beam judges just decide that the Swedish team was a team that deserved to be in the 8.9 to 9.1 range?

- It’s hard to tell without seeing all of the compulsory beam routines.

- Did the Swedish team learn the compulsory beam routine incorrectly?

- I don’t know, but as you saw, the compulsory routines were difficult to interpret.

- If your country misinterpreted the routine, chances were that all the gymnasts would make the same mistakes, resulting in the same deductions across the team.

A Few Remarks on the Optional Footage

Čáslavská on BB (16:40): As I pointed out in the 1962 World Championships commentary, Čáslavská had more acrobatic routines than many of her competitors.

- Her back walkover to back walkover swing down (the strength it took to save the second back walkover!) was rare in 1964.

- While many of her competitors performed cartwheels in isolation, Čáslavská performed a cartwheel in combination for her dismount.

- In short, Čáslavská helped push the event in a more acrobatic direction.

Bedford on UB (19:11): There are obvious form issues and pause breaks in this routine, but it shows some of the classic uneven bar moves:

- A wrap around the low bar to eagle grip on the high bar

- A dislocate (19:27)

- A mill/stride circle

- A cut catch on the high bar (19:47).

Čáslavská on FX (20:48): As we saw on beam, Čáslavská had a solid dance background, but she didn’t rely solely on her dance. She paired her dance abilities with challenging acrobatics for the time:

- Two aerial cartwheels to a back handspring to her knees.

- Three butterflies to an illusion turn, and afterwards, she stood up in back attitude as if to say, “Yeah, I can do it all — both tumbling and ballet.”

- Plus, she started and finished with a layout.

At the end, you can see that the crowd loved it.

Latynina on FX (39:16): Latynina performed an entire ballet for the audience, including both the female and male parts. You can see this best at the 40:15 mark.

- First, she dances as if she were doing pointe work.

- Then, shortly after performing a dive cartwheel into the corner, she breaks into traditionally masculine ballet moves (i.e. high-flying, complex leaps and jumps that hang in the air):

- A playful take on a saut de basque

- A switch leap

- A tour (jump full turn) that ends in the splits rather than on one knee, as male ballet dancers often perform it.

It was an exquisite routine. 🙌

Team Competition

Reminder: Teams consisted of 6 members. The best 5 scores on each event counted for both compulsories and optionals.

Here were the groupings for the women’s competition:

- Group A (8:30 am / 7:00 pm)

- Hungary (Vault)

- Soviet Union (Bars)

- Japan (Beam)

- USA (Floor)

- Group B (10:30 am / 5:00 pm)

- France, Belgium, Iran (Vault)

- Germany (Bars)

- Sweden (Floor)

- Group C (5:00 pm / 10:30 am)

- Australia (Vault)

- Austria, Finland, Philippines (Bars)

- Czechoslovakia (Beam)

- Bulgaria, Korea (Floor)

- Group D (7:00 pm / 8:30 am)

- Great Britain, Canada, Mongolia (Vault)

- Poland (Bars)

- Romania (Beam)

- Taiwan, New Zealand, Portugal (Floor)

The first time listed was for compulsories on October 19, and the second time listed was for optionals on October 21. The rotation order remained consisted between compulsories and optionals. For example, Czechoslovakia always started on beam.

| Nation | VT | UB | BB | FX | Total |

| 1. USSR | |||||

| Comp. | 47.399 | 47.632 | 46.998 | 47.699 | 189.728 |

| Opt. | 47.632 | 47.032 | 48.466 | 48.032 | 191.162 |

| Total | 95.031 | 94.664 | 95.464 | 95.731 | 380.890 |

| 2. Czechoslovakia | |||||

| Comp. | 47.432 | 47.332 | 47.098 | 46.833 | 188.695 |

| Opt. | 47.799 | 47.832 | 48.165 | 47.498 | 191.294 |

| Total | 95.231 | 95.164 | 95.263 | 94.331 | 379.989 |

| 3. Japan | |||||

| Comp. | 47.598 | 46.964 | 46.398 | 47.033 | 187.993 |

| Opt. | 47.499 | 47.532 | 47.366 | 47.499 | 189.896 |

| Total | 95.097 | 94.496 | 93.764 | 94.532 | 377.889 |

| 4. Germany | |||||

| Comp. | 47.432 | 46.765 | 46.565 | 47.298 | 188.060 |

| Opt. | 47.232 | 46.931 | 46.683 | 47.132 | 187.978 |

| Total | 94.664 | 93.696 | 93.248 | 94.430 | 376.038 |

| 5. Hungary | |||||

| Comp. | 46.498 | 46.732 | 46.732 | 47.299 | 187.261 |

| Opt. | 46.598 | 47.266 | 47.298 | 47.032 | 188.194 |

| Total | 93.096 | 93.998 | 94.030 | 94.331 | 375.455 |

| 6. Romania | |||||

| Comp. | 46.531 | 46.364 | 46.230 | 45.632 | 184.757 |

| Opt. | 46.698 | 46.998 | 46.999 | 46.532 | 187.227 |

| Total | 93.229 | 93.362 | 93.229 | 92.164 | 371.984 |

| 7. Poland | |||||

| Comp. | 46.632 | 45.566 | 46.231 | 46.065 | 184.494 |

| Opt. | 46.799 | 45.965 | 46.964 | 47.065 | 186.793 |

| Total | 93.431 | 91.531 | 93.195 | 93.130 | 371.287 |

| 8. Sweden | |||||

| Comp. | 46.665 | 46.366 | 45.366 | 45.832 | 184.229 |

| Opt. | 46.164 | 45.265 | 46.232 | 45.998 | 183.659 |

| Total | 92.829 | 91.631 | 91.598 | 91.830 | 367.888 |

| 9. USA | |||||

| Comp. | 46.599 | 46.031 | 45.065 | 46.265 | 183.960 |

| Opt. | 45.932 | 43.932 | 46.898 | 46.599 | 183.361 |

| Total | 92.531 | 89.963 | 91.963 | 92.864 | 367.321 |

| 10. Australia | |||||

| Comp. | 44.032 | 39.398 | 43.732 | 44.065 | 171.227 |

| Opt. | 42.631 | 41.298 | 42.998 | 44.081 | 171.008 |

| Total | 86.663 | 80.696 | 86.730 | 88.146 | 342.235 |

Note: The rank order of the teams hardly changed after compulsories. Japan was able to capitalize on Germany’s weak performances on optional bars and beam to move into third place.

Standings after Compulsories

| Comp. Ranking | Comp. Score | Final Ranking |

| 1. USSR | 189.728 | 1 |

| 2. Czechoslovakia | 188.695 | 2 |

| 3. Germany | 188.060 | 4 |

| 4. Japan | 187.993 | 3 |

| 5. Hungary | 187.261 | 5 |

| 6. Romania | 184.757 | 6 |

| 7. Poland | 184.494 | 7 |

| 8. Sweden | 184.229 | 8 |

| 9. USA | 183.960 | 9 |

| 10. Australia | 171.227 | 10 |

On Team USA

Vannie Edwards, the team’s coach, wrote an article for Modern Gymnast, summarizing their experience. Here are a few tidbits:

- Leading up to the Games, the team trained together at the Los Angeles Athletic Club, using Nissen apparatus.

- While in California, Doris Fuchs fell off uneven bars and injured both elbows. She was still struggling in Tokyo and was made the alternate.

- Edwards believed that the team would have finished sixth if it had not been for a bad uneven bars rotation during the optionals competition.

- Janie Speaks was the lead-off gymnast and fell on her dismount (8.166)

- Muriel Grossfeld was second and fell on a drop kip (8.133).

- Marie Walthers competed last. She had two bad breaks and fell on her dismount (7.500).

- Edwards was blunt (and had internalized America’s culture of sexism).

- “As girls will be, there were a few flares of temper but nothing too extreme.”

- “We definitely blew at least three points in the uneven parallel bars.”

The All-Around

Reminder: There wasn’t a separate all-around competition as there is today. At the same time that gymnasts were competing for the team title, they were competing for the all-around title. Their all-around totals were the sum of their optional and compulsory routines.

Rankings after Compulsories – Top 10

| Comp. Score | Final Ranking | |

| 1. Čáslavská | 38.432 | 1 |

| 2. Latynina | 38.199 | 2 |

| 2. Astakhova | 38.199 | 3 |

| 4. Radochla | 38.165 | 4 |

| 5. Aihara | 37.965 | 7 |

| 6. Ikeda | 37.898 | 6 |

| 7. Starke | 37.866 | 10 |

| 8. Volchetskaya | 37.832 | 8 |

| 9. Manina | 37.799 | 15 |

| 10. Růžičková | 37.699 | 5 |

| 10. Föst | 37.699 | 12 |

Heading into the optional portion of the competition, Čáslavská was the frontrunner. She was able to hold off Latynina and Astakhova to win gold, ending the Soviet Union’s winning streak in the all-around (1952: Gorokhovskaya; 1956: Latynina; 1960: Latynina).

Final All-Around Standings – Top 20

| VT | UB | BB | FX | Total | ||

| 1. Čáslavská | TCH | 77.564 | ||||

| C. | 9.700 | 9.666 | 9.566 | 9.500 | 38.432 | |

| O. | 9.800 | 9.766 | 9.800 | 9.766 | 39.132 | |

| 2. Latynina | URS | 76.998 | ||||

| C. | 9.500 | 9.533 | 9.500 | 9.666 | 38.199 | |

| O. | 9.666 | 9.600 | 9.733 | 9.800 | 38.799 | |

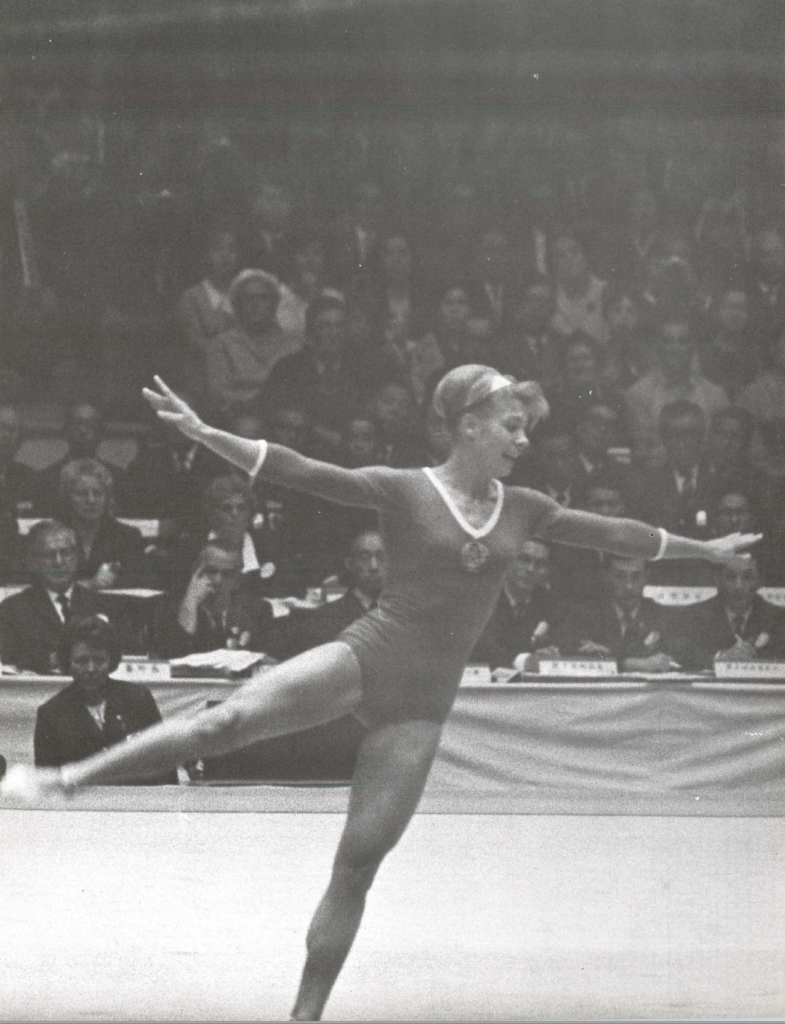

| 3. Astakhova | URS | 76.965 | ||||

| C. | 9.466 | 9.633 | 9.400 | 9.700 | 38.199 | |

| O. | 9.566 | 9.700 | 9.800 | 9.700 | 38.766 | |

| 4. Radochla | GER | 76.431 | ||||

| C. | 9.766 | 9.433 | 9.400 | 9.566 | 38.165 | |

| O. | 9.600 | 9.500 | 9.533 | 9.633 | 38.266 | |

| 5. Růžičková | TCH | 76.097 | ||||

| C. | 9.433 | 9.400 | 9.466 | 9.400 | 37.699 | |

| O. | 9.433 | 9.633 | 9.766 | 9.566 | 38.398 | |

| 6. Ikeda | JPN | 76.031 | ||||

| C. | 9.466 | 9.466 | 9.466 | 9.500 | 37.898 | |

| O. | 9.533 | 9.300 | 9.700 | 9.600 | 38.133 | |

| 7. Aihara | JPN | 75.997 | ||||

| C. | 9.633 | 9.466 | 9.333 | 9.533 | 37.965 | |

| O. | 9.600 | 9.633 | 9.266 | 9.533 | 38.032 | |

| 8. Volchetskaya | URS | 75.765 | ||||

| C. | 9.633 | 9.400 | 9.366 | 9.433 | 37.832 | |

| O. | 9.600 | 9.233 | 9.600 | 9.500 | 37.933 | |

| 9. Ono | JPN | 75.665 | ||||

| C. | 9.500 | 9.366 | 9.233 | 9.400 | 37.499 | |

| O. | 9.466 | 9.600 | 9.500 | 9.600 | 38.166 | |

| 10. Starke | GER | 75.632 | ||||

| C. | 9.600 | 9.433 | 9.333 | 9.500 | 37.866 | |

| O. | 9.500 | 9.433 | 9.400 | 9.433 | 37.766 | |

| 11. Sedláčková | TCH | 75.598 | ||||

| C. | 9.433 | 9.366 | 9.400 | 9.300 | 37.499 | |

| O. | 9.500 | 9.600 | 9.566 | 9.433 | 38.099 | |

| 12. Föst | GER | 75.465 | ||||

| C. | 9.500 | 9.300 | 9.366 | 9.533 | 37.699 | |

| O. | 9.500 | 9.366 | 9.300 | 9.600 | 37.766 | |

| 13. Zamotaylova | URS | 75.398 | ||||

| C. | 9.366 | 9.533 | 9.200 | 9.400 | 37.499 | |

| O. | 9.400 | 9.533 | 9.533 | 9.433 | 37.899 | |

| 14. Iovan | ROU | 75.397 | ||||

| C. | 9.433 | 9.433 | 9.366 | 9.266 | 37.498 | |

| O. | 9.466 | 9.533 | 9.500 | 9.400 | 37.899 | |

| 14. Manina | URS | 75.397 | ||||

| C. | 9.400 | 9.433 | 9.466 | 9.500 | 37.799 | |

| O. | 9.366 | 8.966 | 9.800 | 9.466 | 35.598 | |

| 16. Tkačíková | TCH | 75.331 | ||||

| 9.400 | 9.400 | 9.366 | 9.333 | 37.499 | ||

| 9.566 | 9.333 | 9.533 | 9.400 | 37.832 | ||

| 16. Ducza-Jánosi | HUN | 75.331 | ||||

| C. | 9.266 | 9.166 | 9.433 | 9.600 | 37.465 | |

| O. | 9.400 | 9.400 | 9.466 | 9.600 | 37.866 | |

| 18. Makray | HUN | 75.330 | ||||

| C. | 9.133 | 9.566 | 9.333 | 9.466 | 37.498 | |

| O. | 9.266 | 9.600 | 9.466 | 9.500 | 37.832 | |

| 19. Nakamura | JPN | 75.198 | ||||

| C. | 9.533 | 9.400 | 9.133 | 9.300 | 37.366 | |

| O. | 9.400 | 9.566 | 9.466 | 9.400 | 37.832 | |

| 20. Leușteanu-Popescu | ROU | 75.130 | ||||

| C. | 9.266 | 9.366 | 9.366 | 9.300 | 37.298 | |

| O. | 9.366 | 9.400 | 9.533 | 9.533 | 37.832 |

Shortly after the Tokyo Olympics, Ikeda Keiko tore her Achilles during floor warm-ups at the Japanese Nationals, which were held November 20-23, 1964 (Modern Gymnast, May/June 1965). She recovered in time for the 1966 World Championships, where she won two bronze medals.

Team Canada Drama

I’m including this story because it seems illustrative of the times, particularly the sexism in sports and the attitudes about name recognition in judging. So, here we go…

The C.O.A. [Canadian Olympic Association] voted to send the top three gymnasts (male and/or female), based on the Vancouver gymnastlc trials, to the 1964 Olympic Games. At the trials Gail Daley retained her Senior Canadian Women’s title and, in the process, defeated gymnasts who were members of the U.S. Women’s Olympic team. However, when the Canadian Olympic Team selections were made it was decided to send a team composed of three men, Richard Kihn, Gilbert Larose and Wilhelm Weiler. This was decided in spite of the fact that Gail Daley’s average mark was higher than those of Gilbert Larose or Wilhelm Weiler. One of the main reasons why Weiler was picked over Gail Daley was “. . that his name would be worth half a point an exercise, and by selecting him it would carry weight because he is well known in Europe Many felt that this decision to overlook the top Canadian female gymnast, and to send a three man team, was a major setback to gymnastics in Canada. A coast-to-coast squabble resulted, with the citizens of Saskatoon playing a major role. The city of Saskatoon donated money to the Canadian Olympic Team General Fund which would more than cover the expense involved for Gail Daley. Finally, on September 12th it was recommended that the gymnastics team be increased to four competitors (Gail Daley, Saskatoon, Richard Kihn, Toronto, Gilbert Larose, Montreal and Wilhelm Weiler, Camp Chilliwack, B.C.) and one official (Chuck Sebestyen, Saskatoon, as manager-coach).

Reet Nurmberg, A History of Competitive Gymnastics in Canada, 1970

Here’s the TL;DR:

- Canada wasn’t going to send any gymnasts to Tokyo. Then, they were going to send only three gymnasts to Tokyo.

- Gail Daley won Canadian nationals but wasn’t chosen. Instead, three men were chosen, which upset a lot of people.

- One of those men (Wilhelm Weiler of the Weiler kip fame) was chosen because of his name.

- Daley’s hometown of Saskatoon kicked in money to help send her to Tokyo.

- Daley ended up being the most accomplished Canadian at the Olympics, winning the FIG pin, which was given to gymnasts who maintained or exceeded a 9-point average on both compulsory and optional exercises.

Side note for college gymnastics fans: Daley went on to compete for Southern Illinois University.

Event Finals

Reminder: Only six gymnasts qualified for event finals. Qualification for finals was based on the compulsory *and* optional scores on each event.

Your total score was the average of your compulsory and optional scores (labeled “COA” in the tables below) plus the score for your routine during event finals.

Vault

| Country | Finals | COA | Total | |

| 1. Čáslavská | TCH | 9.733 | 9.750 | 19.483 |

| 2. Latynina | URS | 9.700 | 9.583 | 19.283 |

| 2. Radochla | GER | 9.600 | 9.683 | 19.283 |

| 4. Aihara | JPN | 9.666 | 9.616 | 19.282 |

| 5. Volchetskaya | URS | 9.533 | 9.616 | 19.149 |

| 6. Starke | GER | 9.566 | 9.550 | 19.116 |

Ouch, Aihara missed out on a silver medal by 0.001.

Uneven Bars

| Country | Finals | COA | Total | |

| 1. Astakhova | URS | 9.666 | 9.666 | 19.332 |

| 2. Makray | HUN | 9.633 | 9.583 | 19.216 |

| 3. Latynina | URS | 9.633 | 9.566 | 19.199 |

| 4. Aihara | JPN | 9.233 | 9.549 | 18.782 |

| 5. Čáslavská | TCH | 8.700 | 9.716 | 18.416 |

| 6. Zamotaylova | URS | 8.300 | 9.533 | 17.833 |

Čáslavská on UB in Finals: Unfortunately, the competition footage above doesn’t include event finals footage, but there is footage of Čáslavská’s bar routine from finals, where she fell. (Even the best fall sometimes.)

Keep in mind that some men were competing the uprise 1/1 at the time. In fact, Ono Takashi performed the skill during event finals at the 1964 Olympic Games.

In Věra 68 (2012), Čáslavská said that she looked up to the Japanese men and learned the uprise 1/1 from them. At the time, it was the only “Ultra C” element, according to Čáslavská.

Regarding this particular routine, she recalled a teammate cheering for her at the exact moment that she fell. But she got up to do it again because she “knew that the Japanese really wanted to see me do it.”

In the U.S. gymnastics media, Čáslavská‘s straddle toe shoot to the high bar was the talk of the town. “This move when seen for the first time has the startling illusion of a flip catch between the bars” (Modern Gymnast, March 1965).

Balance Beam

| Country | Finals | COA | Total | |

| 1. Čáslavská | TCH | 9.766 | 9.683 | 19.449 |

| 2. Manina | URS | 9.766 | 9.633 | 19.399 |

| 3. Latynina | URS | 9.766 | 9.616 | 19.382 |

| 4. Astakhova | URS | 9.766 | 9.600 | 19.366 |

| 5. Růžičková | TCH | 9.733 | 9.616 | 19.349 |

| 6. Ikeda | JPN | 9.633 | 9.583 | 19.216 |

My thought bubble: Four athletes received a 9.766 in finals. Hmm… I thought that judges were supposed to differentiate between routines.🤔

Floor Exercise

| Country | Finals | COA | Total | |

| 1. Latynina | URS | 9.866 | 9.733 | 19.599 |

| 2. Astakhova | URS | 9.800 | 9.700 | 19.500 |

| 3. Ducza-Jánosi | HUN | 9.700 | 9.600 | 19.300 |

| 4. Radochla | GER | 9.700 | 9.599 | 19.299 |

| 5. Föst | GER | 9.700 | 9.566 | 19.266 |

| 6. Čáslavská | TCH | 9.466 | 9.633 | 19.099 |

Ouch again, Radochla missed out on a medal by 0.001.

Čáslavská fell during floor finals. Here’s what was reported at the time:

A Soviet woman judge was sharply criticized by the crowd for her partisan attitude in scoring.

Maria Gorokhovskaya gave the lowest score to the Czech blonde [Čáslavská] after her accident.

Earlier, the same judge had, in the women’s beam, given the highest score to the Soviet gymnast Latynina allegedly in order to heighten her chances of beating Caslavska for the gold medal.

The judge’s partiality aroused protests from the spectators, even from Soviet members in the crowd.

The Yomiuri, Oct. 24, 1964

Reminder: This was before closed scoring. The spectators could see each individual judge’s scores.

Gym Nerdery at Its Finest

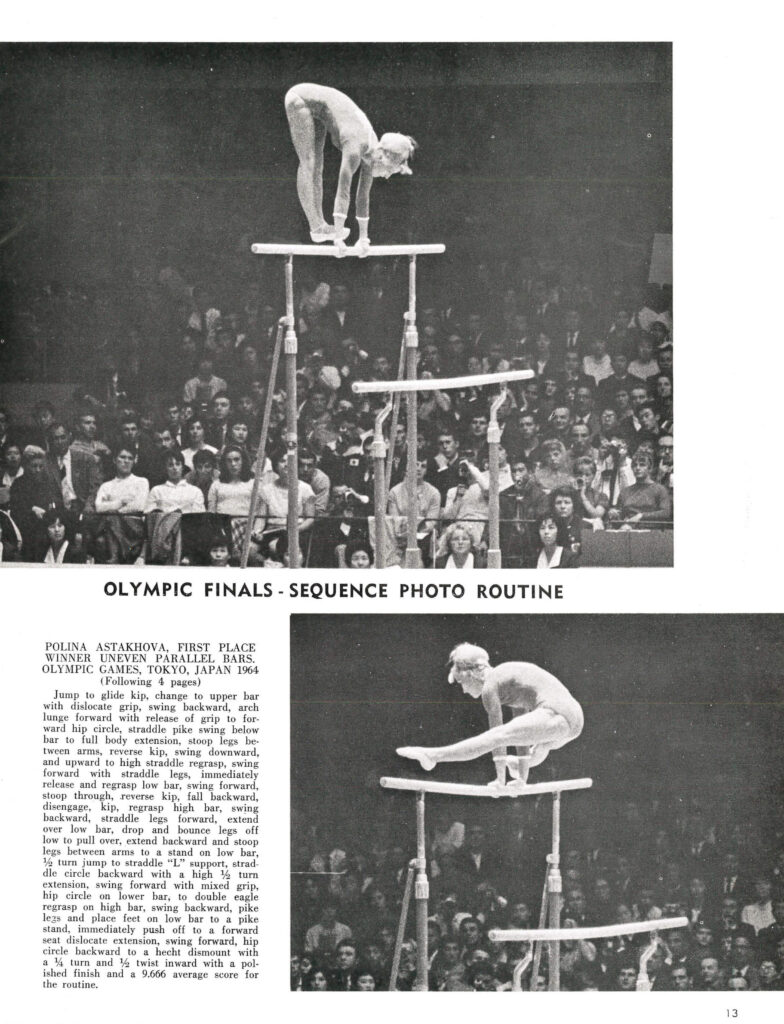

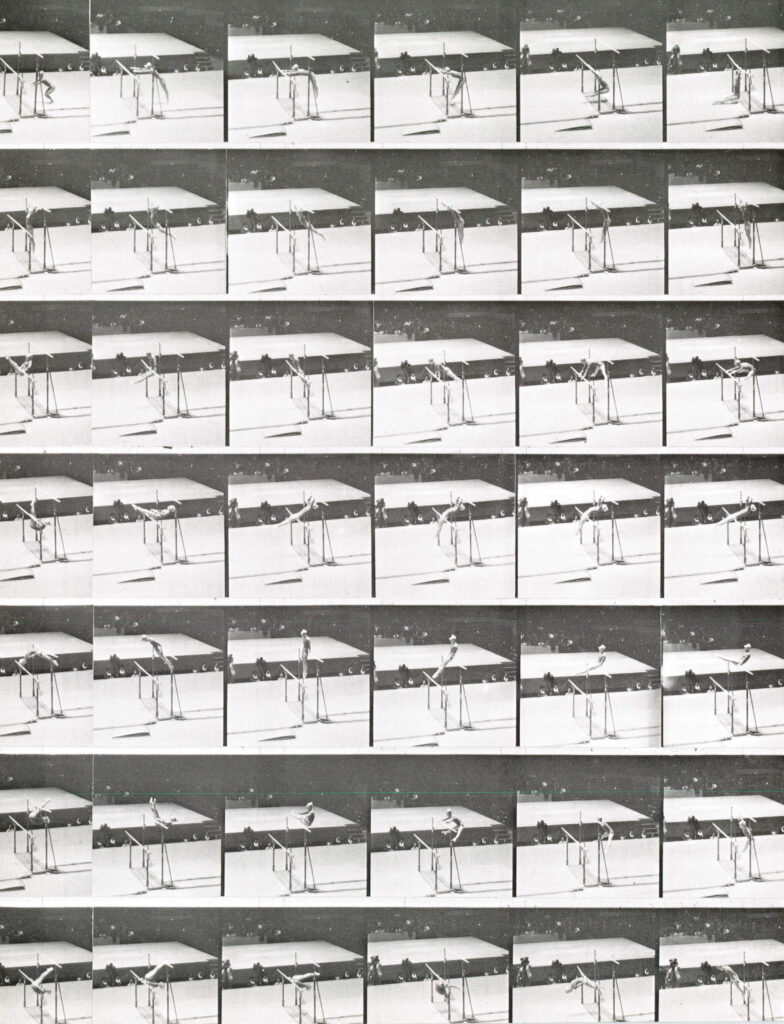

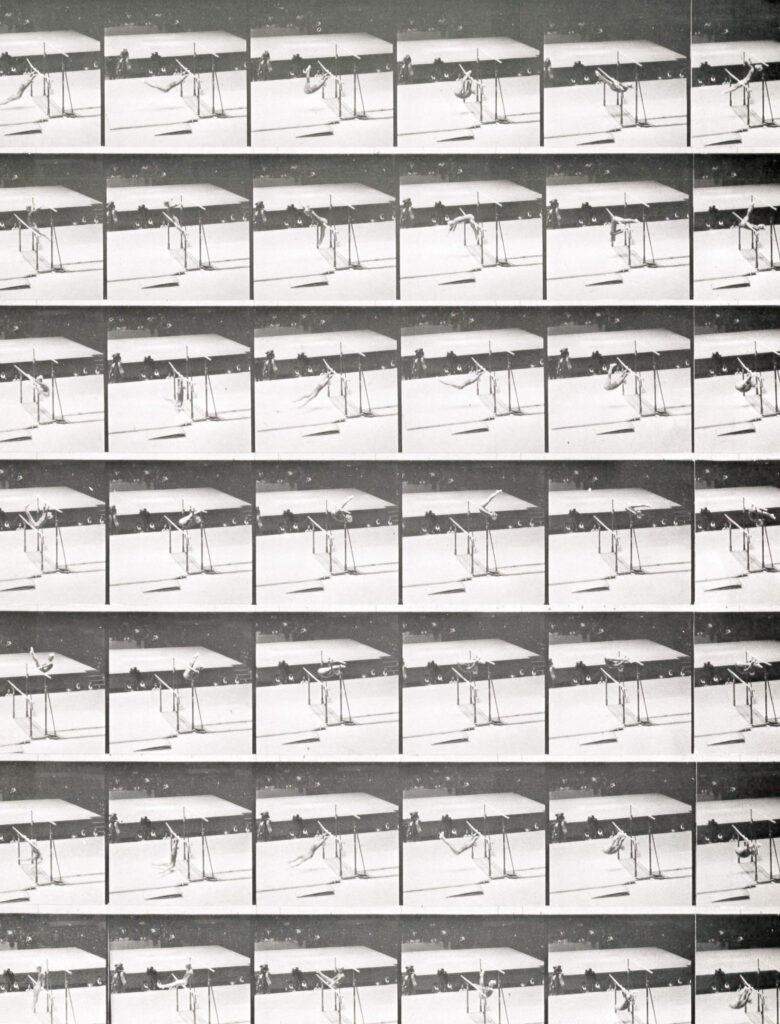

Since videos were not easily accessible, the magazine Modern Gymnast transcribed the moves in select routines for its readers.

For big events, like the Olympics, the magazine included frame-by-frame photomontages of the routines.

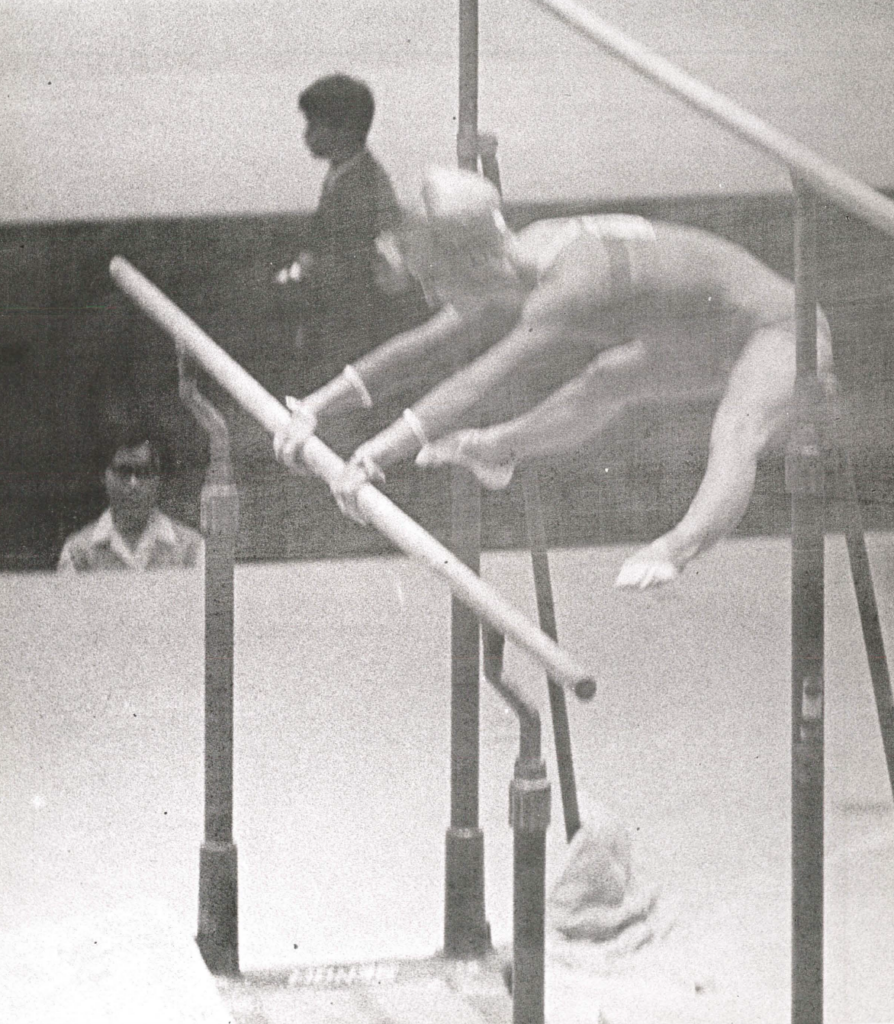

For example, here is the description of Astakhova’s bar routine:

Jump to glide kip, change to upper bar with dislocate grip, swing backward, arch lunge forward with release of grip to forward hip circle, straddle pike swing below bar to full body extension, stoop legs between arms, reverse kip, swing downward, and upward to high straddle regrasp, swing forward with straddle legs, immediately release and regrasp low bar, swing forward, stoop through, reverse kip, fall backward, disengage, kip, regrasp high bar, swing backward, straddle legs forward, extend over low bar, drop and bounce legs off low to pull over, extend backward and stoop legs between arms to a stand on low bar, ½ turn jump to straddle “L” support, straddle circle backward with a high 1/2 turn extension, swing forward with mixed grip, hip circle on lower bar; to double eagle regrasp on high bar, swing backward, pike legs and place feet on low bar to a pike stand, immediately push off to a forward seat dislocate extension, swing forward, hip circle backward to a hecht dismount with a 1/4 turn and 1/2 twist inward with a polished finish and a 9.666 average score for the routine.

Modern Gymnast, May/June 1965

And here’s the photomontage.

The End of an Era

Not only did Latynina lose the all-around title to Čáslavská in Tokyo; she came home and lost the all-around title at the Soviet Nationals…

…to a 15 year-old.

In fact, she *almost* lost to two 15-year-olds. In April of 1965, the Modern Gymnast reported on the USSR National competition that took place in Kyiv on December 11-13, 1964:

The women’s competition proved even more sensational. For the first time, four 15 year-old girls were in the finals. They had their first gymnastic steps only four years ago while Larisa Latynina was the All-Around Olympic Champion. Now a school girl Larisa Petrik, 15 years of age from the small town of Vitebsk, occupied the top of the pedestal. Natalia Kuchinskaya also caused much excitement among the spectators. She was the leader after three events but unfortunately, she slipped from the Balance Beam and received a lower score. Nevertheless her future smiles upon her.

Note: You can read the Soviet coverage of Petrik’s victory here, and you can read Latynina’s thoughts on both the Tokyo Olympics and Petrik here.

To be clear, this wasn’t the first time that teenagers (or younger) were participating in gymnastics.

- At the 1964 Olympics, the youngest female competitor was 14.

- In 1964, Janie L. Speaks, a 16-year-old, was Team USA’s lead-off gymnast in Tokyo.

- In 1963, 10-year-old Glenna Sebestyen was the second-best gymnast during the Canadian Pan-American Trials.

But, but, but

- A 15 year-old winning in the Soviet Union mattered a LOT because the Soviet Union was at the top of the sport.

- And it mattered even more because these young teenagers had toppled Larisa Latynina, the long-time queen of Soviet gymnastics.

A new era was coming.

Yes, Věra Čáslavská would continue for another Olympics, but the results of the USSR Nationals showed that the age pendulum was swinging in a younger direction.

And the 1966 World Championships–not the 1972 Olympics with Olga or 1976 Olympics with Nadia–would mark a clear turning point for women’s gymnastics.

We’ll get to the 1966 World Championships, but first, we need to discuss the men’s competition in Tokyo.

Spoiler alert: Once again, there was a major judging controversy, and once again, the gymnastics community called the 10.0 scoring system into question.