In Věra ‘68, Čáslavská returned to the National Auditorium in Mexico City, the place where she won four gold medals. While there, the tour guide said:

[Čáslavská] was an icon for us. We felt she was one of us, because at that time, in both our countries, there were student uprisings. That is why she was so dear to us. The fact that she won — it strengthened the bond between all the oppressed people. You will always be in our hearts.

During the 1968 Olympic Games, the Czechoslovak athletes meant a lot to a large portion of the Mexican audience. To understand why, you have to understand what happened in Mexico City ten days before the Olympics commenced.

The headline reads, “Army’s firefight with students.”

A Quick Summary | The Parallels with Czechoslovakia | The IOC President’s Reaction | What Has Been Revealed Since

A Quick Summary: The Tlatelolco Massacre

A summer of tension between student protestors and the Mexican police and military exploded on October 2, 1968, ten days before the Opening Ceremonies were scheduled to kick off the Olympic Games.

Around 5:30, on the evening of October 2, a crowd of roughly 10,000 gathered for a rally in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in the Tlatelolco housing complex. They were there to hear speeches from the movement’s leaders and to protest the unjust imprisonment of their countrymen by the repressive Mexican government.

According to El Informador’s account, printed on October 3, as the organizers spoke, helicopters were circling in the sky. After the speeches were finished, three flares were seen around 6:10 pm, and the police moved into the square. Then, gunfire broke out.

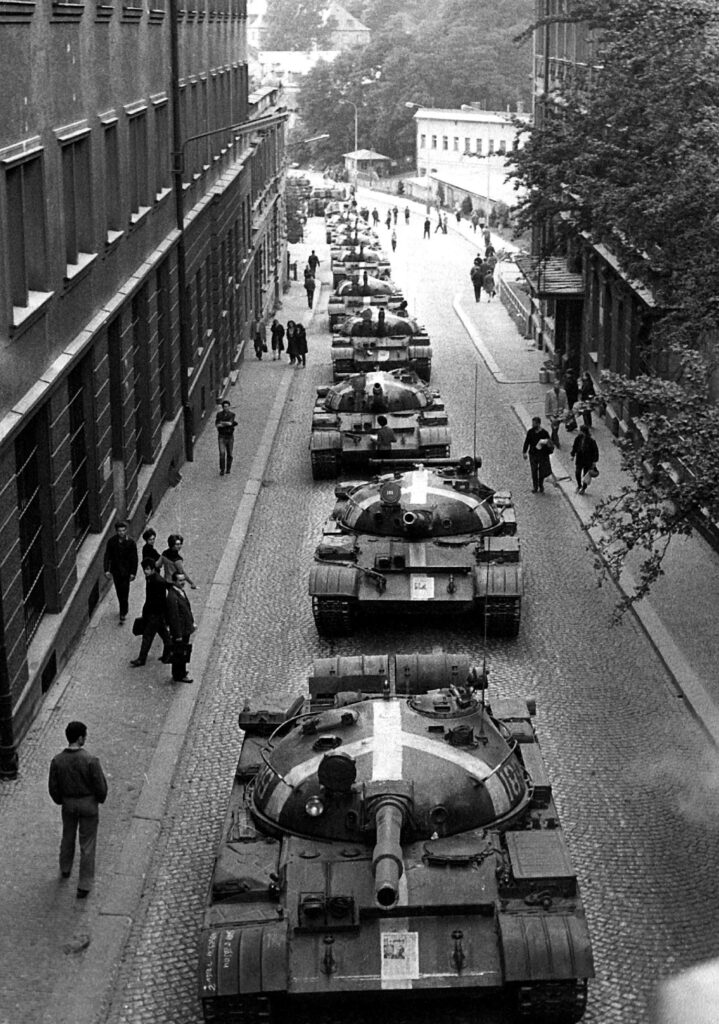

At the time, no one knew who first opened fire. But the military quickly acted. Machine guns were fired. Tanks rolled in, and even after the security forces had taken control of the square, the gunfire didn’t cease.

Journalists were forced to lie face down. Their cameras were destroyed.

The students were rounded up, confined, stripped naked, and beaten. (We’d later find out that many were killed.)

On October 3, Mexican newspapers reported that at least seven people were dead, and over 100 were injured. On October 5, the New York Times reported that at least 29 people lost their lives.

However, no one knew for sure how many died because the bodies were carried away under suspect circumstances. As El Informador reported, the Red Cross was unable to take away the dead bodies. Instead, the remains of the deceased were taken away in military trucks.

To where? No one knew.

The Official Story at the Time

According to the official version given by the military leaders at the time, General José Hernández Toledo was fired upon by the student protesters, which resulted in him being gravely injured and which prompted the military police to respond violently.

Two Opposing Theories Emerged

Was it a foreign plot?

Or was it the Mexican government’s effort to silence the protestors before the Olympics?

On October 5, 1968, Henry Giniger reported in the New York Times:

Government supporters revived their talk of an outside or foreign plot against Mexico by agitators who provoked the army by sniper fire, into shooting during a student meeting Wednesday. But eyewitness accounts of soldiers indiscriminately firing into the crowds, and the circumstances surrounding the clash, suggest to some observers a deliberate Government effort to terrorize the students into quiescence at least for the period of the Olympic Games, which open here Oct. 12 and run through the Oct. 27.

When the Olympics started, many had their suspicions about what had happened, but the details were murky. A clearer picture wouldn’t take shape until much later when classified documents were unsealed.

To find out some details that were later revealed, jump to the bottom of the page.

Spoiler: The government was at fault.

The Parallels between Czechoslovakia and Mexico

Čáslavská was the star of the Olympic Games. That’s largely thanks to her exceptional athletic talents. But it shouldn’t be forgotten that a certain portion of the Mexican public felt a kinship with her and the rest of the Czechoslovak Olympians.

In 1968, women’s gymnastics team from Czechoslovakia won the silver behind the Soviet team. When the women’s team medals were being handed out, the crowd was cheering for Čáslavská — and the Czechoslovak people:

The public acclaimed the Czechoslovak people* and yelled, “VĚRA VĚRA” during the team medal ceremony for women’s gymnastics, a competition that the Soviets won, followed by the Czechs.

El público aclamó hoy a los checoslovacos y gritó “VERA VERA” durante la ceremonia de entrega de medalla en gimnasia femenina por equipos, prueba que ganaron las soviéticas seguidas de las checas.

Informador, Oct. 24, 1968

*In Spanish, the writer uses “los checoslovacos” instead of “las checoslovacas,” which indicates that the public was cheering for the Czechoslovak people — not just the female gymnasts.

As most gym nerds know…

- During the Prague Spring, Dubček attempted to decentralize the economy and loosen restrictions on the media, speech, and travel.

- On June 17, 1968, the intellectuals and artists of Czechoslovakia signed the 2,000 Words manifesto, which showed support for the opening of Czechoslovakia. Čáslavská also signed the document.

- Between the night of August 20 and the morning of August 21, a Soviet-led invasion took place. Roughly 200,000 troops and 2,000 tanks entered Czechoslovakia.

- The Soviet Special Forces began arresting the leaders of the Prague Spring.

- At the time, Čáslavská was at a training camp near Šumperk. Scared for her safety, she went into hiding in a remote cabin in the woods. She shoveled coal to keep her calluses and worked out on makeshift apparatuses.

Note: It wasn’t a secret that Čáslavská signed the manifesto. It was worldwide news. On July 5, 1968, The Times of London reported:

The appeal is called ‘Two thousand words.” It was drafted by Mr. Ludvik Vaculik, the rebellious writer who was expelled from the Communist Party last year but has since been reinstated. The signatories include Professor Oldrich Stary. Rector of Charles University; Mr. Jiri Menzel, the film director; Miss Vera Caslavska, the Tokyo Olympic medallist; Professor Pavel Lukl, president of the Cardiological Society; and Mr. Emil Zatopek, the Olympic runner.

And Čáslavská gave interviews about it:

Vera Caslavska, Czechoslovakia’s world champion gymnast and chief hope for a new gold medal, said in an interview published today that the Soviet invasion sent her into hiding and hampered her preparation for the Mexico Olympics.

Apparently referring to her Soviet rivals, the Czech athlete added definitely that she will “do everything to show some competitors what gymnastics mean in Czechoslovakia.”

“Everything must come back to normal soon,” she said to a reporter of the trade union daily “Prace.” “One cannot live long under the present circumstances. One’s nerves cannot endure it.”

The blonde world star was one of the signers of the “2,000 word manifesto” drafted by liberal communists and noncomunists. It was specifically denounced in the Soviet attacks preceding the invasion.

She said she and other members of the Czechoslovak gymnastic team had been practicing in the town of Sumperk when Soviet troops marched into the country.

“All of us were shocked. No one thought of training. There were rumors that measures would be taken against all those who had signed the 2,000 words. I was not afraid, but it was recommended to me that I should leave.”

“I stayed with very brave people whose name I will not mention. For five days I could not do any training. Therefore, I helped the people store coal in their basement. It was an excellent workout.”

The Yomiuri, Sept. 8, 1968

Can you see the parallels between the Prague Spring and Mexico’s student protest movement?

😥 Repressive governments.

😥 Tanks rolling in.

😥 Extreme military presence.

😥 People being arrested for speaking out.

Even the imagery is eerily similar. The first image below: Czechoslovakia. The second image: Mexico.

Adding insult to injury, Avery Brundage, the IOC President, wasn’t bothered by the massacre…

What Avery Brundage, President of the IOC, Had to Say

A massacre had just taken place 10 days before the Opening Ceremonies. You’d think that the IOC President would show some empathy. But he did not.

The initial response

Initially, after the massacre, Brundage said:

“I was at the ballet last night.”

Qtd. in The Games by David Goldblatt

In other words, Brundage knew nothing about what transpired at the Plaza de Tres Culturas, and if he did, he wasn’t bothered. The Games would go on. It was the IOC equivalent of, “Let them eat cake…”

His official statement about a “friendly gathering” contrasted sharply with what had just happened…

“The Games of the 19th Olympiad, this friendly gathering of the youth of the world in fraternal competition, will go ahead as planned.”

« Les Jeux de la 19ème olympiade, cet amical rassemblement de la jeunesse du monde dans une compétition fraternelle, se dérouleront comme prévu.»

L’Express, October 4, 1968

As did his comments about a “peaceful entry…”

“We spoke with the Mexican authorities and we were assured that nothing will prevent, on October 12, the peaceful entry of the Olympic torch into the stadium, nor the unfolding of the competitions that will follow. “

Nous nous sommes entretenus avec les autorités mexicaines et nous avons eu l’assurance que rien n’empêchera, le 12 octobre, l’entrée pacifique sur le stade de la flamme olympique, ni le déroulement des compétitions qui suivront.

L´Express, October 4, 1968

Statement was made on Oct. 3, printed on Oct. 4

Five days after the massacre, he couldn’t hide his callousness.

“If the Olympic Games had to be interrupted every time politicians committed human rights violations, there would never be international sporting events.”

“Si los Juegos Olímpicos tuvieran que ser interrumpidos cada vez que los políticos violan las leyes de la humanidad, jamás habría encuentros deportivos internacionales.”

Informador, Oct. 8, 1968

Statement was made on Oct. 7, printed on Oct. 8

Coincidentally, that quote was front-page news, along with photos of the Soviet women’s gymnastics team.

Note: Some IOC presidents would continue to take a similar stance. In 2001, when Beijing was awarded the 2008 Olympic Games, IOC President Jacques Rogge remarked:

“The IOC is not a political body—the IOC is a sports body. Having an influence on human rights issues is the task of political organizations and human rights organizations.”

The Daily Yomiuri, August 28, 2001

Post-Script: What We Later Found out…

In my synopsis above, I focused primarily on what was reported at the time. Since then, we’ve found out more about the massacre.

Update: The White Gloves

At the time, the Mexican newspaper El Informador reported that the police forces were wearing handkerchiefs on their wrists. They thought it was a sign used by the military and police forces to indicate that they weren’t student protesters.

Other witnesses in the square recall seeing men wearing white gloves. Now, it is commonly believed that the gloves were a sign that these soldiers were part of the Olympia battalion, a special security detail assembled for the Olympic Games.

Update: Who Opened Fire?

At the time, El Informador reported that there were students firing pistols and submachine guns from the windows of the Chihuahua building.

Now, we have a clearer picture of what happened. Declassified documents and archival footage have revealed that the government planned the chaos. Those weren’t students in the windows. The government had planted snipers in the surrounding buildings who opened fire on the Mexican troops, provoking the subsequent assault on the students.

To this day, no one knows how many people died. Between 300 and 400 tends to be the number given.

More from 1968