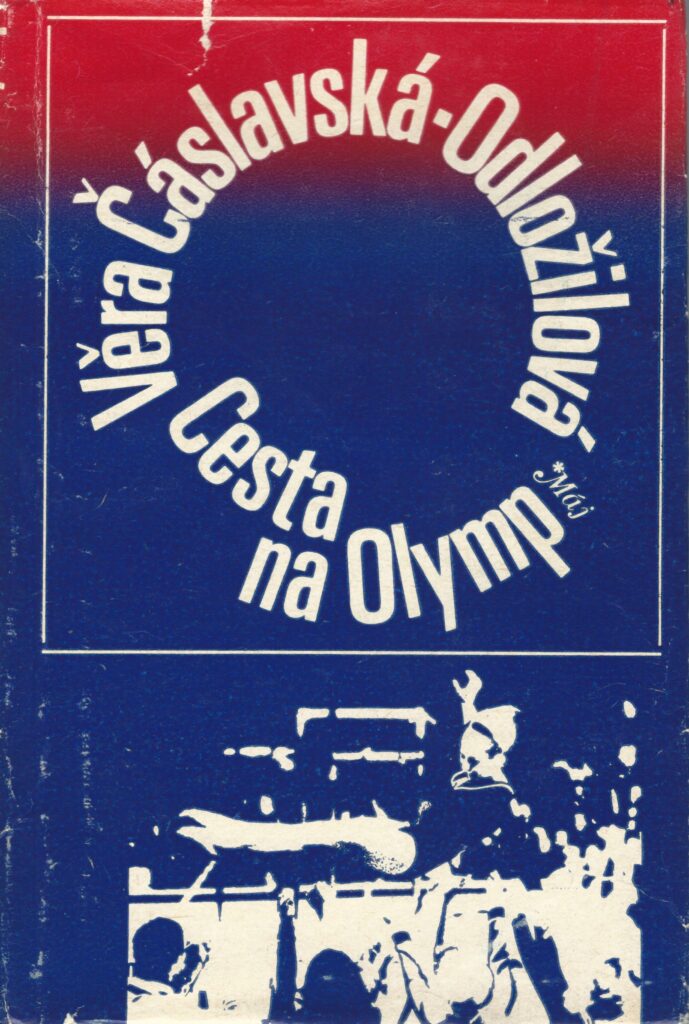

In 1972, Věra Čáslavská published her autobiography, The Road to Olympus (Cesta na Olymp). It provides a detailed recounting of her early days through the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City.

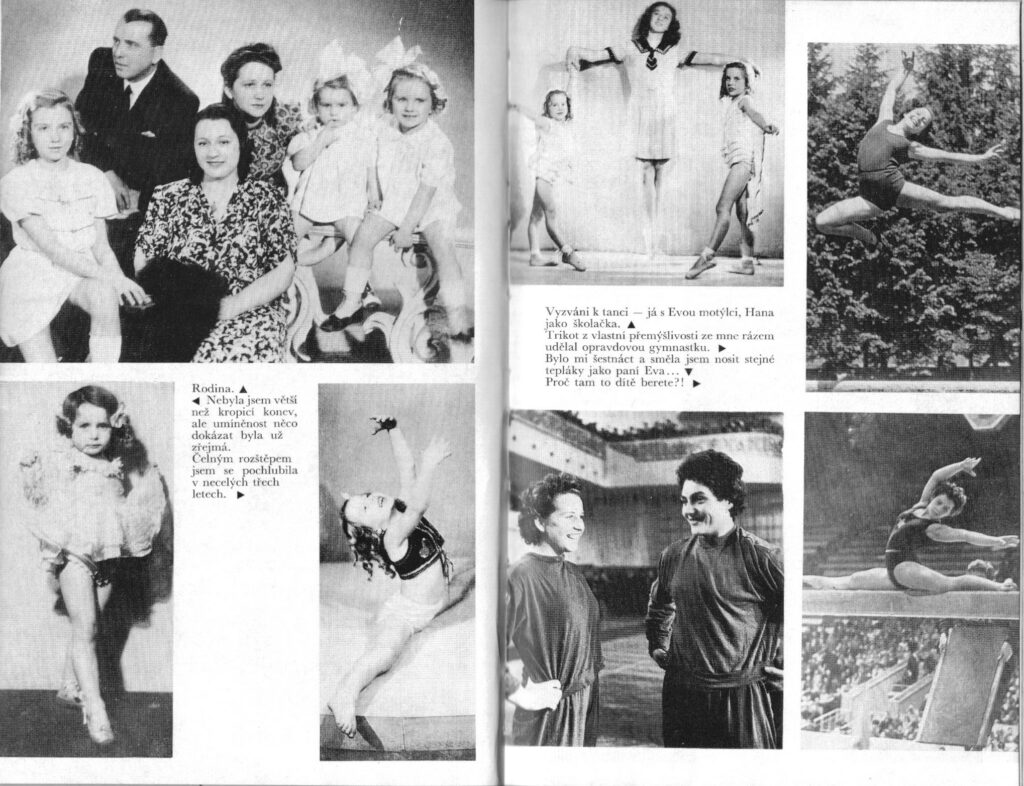

As a child, Čáslavská was a mischievous and funny child. Though a performer at heart, she struggled with stage fright until her mother helped her work through it, and as an adult, she came to see it as an asset.

Čáslavská started with ballet, then added ice skating, and finally found gymnastics. Initially, she trained under Czechoslovak gymnastics legend Eva Bosáková, and when Bosáková was away with the national team, Čáslavská used to sneak into the gym to train. Given her relationship with Bosáková, Čáslavská found it difficult to beat her mentor.

From the start, the international crowd loved Čáslavská. At the age of 16, during her first World Championships in 1958, Čáslavská wowed the audience in Moscow — so much so that the public demanded a performance by Čáslavská, even though she didn’t make the floor finals.

Below, I’ve translated sections of Čáslavská’s autobiography, tracing her early years in sports through to her first World Championships in Moscow in 1958.

Among other things, my mother took care of the culture in the family. Sometimes in the evenings, during festive moments and various junctures, she would play for us gramophone records with famous world singers, and she always knew something about each of them. Her favorites were Enrico Caruso and Benjamin Gigli. At a time when I could not yet read and write properly, I knew many arias, especially Czech and Italian operas.

One day my mother took us to the National Theater to see Swan Lake. She probably shouldn’t have done that. When we got home, with Hanka and Eva [Čáslavská’s sisters], we suddenly turned into prima ballerinas. We turned our best shoes into ballet flats. After, you couldn’t walk normally in them. With the third pair of shoes destroyed, the family council decided that the girls would go to ballet lessons. Otherwise, there would be no peace. The problem was solved, but there was a new one: What about the little one? In ballet, they start at the age of six.

So I was kept in the dressing room like a piece of luggage so as not to disturb anyone. Once I slipped inconspicuously into the hall. At the time, my mom was absorbed in my sister’s ballet performances and didn’t even notice that I was standing in the first row among the others. Madame Aubrecht interrupted the class and asked who I belonged to. Instead of answering, I pointed to Hanka and Evka. Madame (that’s what everyone called Mrs. Aubrecht) started laughing and didn’t want to believe that, instead of one mom, I had two moms, who were only a hair bigger than me. But before I knew it, the real mom caught me and pulled up my skirt to spank me. Mrs. Aubrecht took pity on me and allowed me to try in the corner. I immediately started trying hard, and when my leg swung forward, it was a wonder I didn’t break my nose with my knee. Wow, that was something for me! I was in my element. Mrs. Aubrecht soon began to take notice of me, and what’s more, she began to set me up as a role model for the elders, as well.

Because I wore bright orange swimsuits to ballet lessons, Mrs. Aubrecht called me Pomeranč (Orange). She particularly liked this nickname. When I was practicing well, she called me: “Orange, excellent! Orange, demonstrate how it should be done properly…”

Once I was sitting on the toilet during a break and overheard a conversation among the mothers: “You know, Mrs. Semerádová, that Pomeranč is already pissing me off!” It’s just Pomeranč here, Pomeranč there, it’s a wonder that Aubrecht doesn’t burst from it.” I was very sad about it, and then, for the first time, I understood that people are envious.

The next day, when it was time to go to the ballet, disaster struck. Mom checked our paper cases — and found that the swimsuit, my famous orange swimsuit, was missing. We began to eagerly look for them. But they were not found, they disappeared. It was only a week later, after a long search, that my mother found them. They were hidden behind a wardrobe, cut to pieces. “Hana, Eva, Vera, come here!” she called sternly, and I knew what was coming. She vigorously lined us up, shoved orange cloths in front of each of our noses, and angrily asked, “Who did this?!”

I did not. I didn’t… Me neither. Mom started threatening to beat us up — all three at once. “Two innocent ones will get it — so which one did it?!”

“The mouse did it, Mom. Such a small, grey mouse ran this way and hid there,” — I pointed to the wardrobe. (By the way, mom is very afraid of mice.)

“I’ll show you a mouse, you little rascal! Such a nice swimsuit!” Even the reed didn’t do anything, so it remained the case that the mouse did it.

After about three days, Aunt Šárka talked to me. She came at me very cleverly and cunningly. She took advantage of my momentary openness and said: “Sweetheart, those swimsuits were pretty all cut up — some artist must have done that! I wouldn’t have pulled it off like that myself!” Of course, I jumped at the opportunity and pointed out to my aunt that I was the artist.

My mom dealt with me doubly. Only then did she think about why I actually did it. And so, willingly or not, the divine incident with Mrs. Semerádová and the other mothers had to come to light. I didn’t want Mrs. Aubrecht to praise Pomeranč anymore. So we continued to go to the ballet, but not in orange swimsuits, but in ordinary blue panties and a white T-shirt. But the orange stayed with me once and for all.

[…]

I actually performed in public for the first time when I was less than four years old. I danced the Rag Doll, where I finally used my “zig-zags” [Čáslavská called her flic-flacs “zig-zags”]. I was wearing a pretty white satin dress and a bow in my curls, bigger than I was myself. I remember that stage fright made itself heard even then, although I could not yet define it well enough. Before I entered the stage, already in the dressing room, when my mother was dressing me in the costume, doing my make-up, and preparing me, I was overcome by such a strange constricting feeling. Fortunately, my mother soon sensed this and explained to me that adults also have stage fright, even artists. So I began to be quite proud of my stage fright, but the stage fright didn’t seem to care; it came whenever it wanted and as it wanted, without knocking, before you could say cobbler — I was suddenly in a tight spot. My legs stiffened, my smile petrified. At such moments, my eyes looked imploringly for my mom. She was usually standing somewhere near the stage, behind the scenes, or in the audience. Her facial expressions, which she tried to show me, how I should look and what smile to put on, always made me laugh. Mom looked so funny and comical that I laughed all the way to the dressing room. However, I never got rid of stage fright. Later, when I had done more similar performances, it stopped playing hide-and-seek with me. I uncovered its face and learned to know its weaknesses and strengths, I knew at which moment I could most likely expect it. Sometimes I even managed to trick it, but that was rare. Basically, it was always mean to me. Even when I was, so to speak, a seasoned and experienced competitor, it did not compromise on anything. The fact that it existed, that it was always at hand, and that I was afraid of it, made me do more than I could have done without it.

[…]

I swapped ballet flats for skates and was happy. In a short period of time, I made quite a lot of progress, I really loved the free program, the compulsory program less so. Since my parents were not rich in finances (four children will use up something), no coach would devote himself to me just out of love for the cause. Even my mother did not intend to adopt the manner of standing behind the bar throughout the training and imposing uncritical enthusiasm for her child’s talent. And since I was already a child who was mature enough, my mother left me alone. Those who are said to be capable will apply themselves. She only occasionally came to see, praised, or criticized mistakes. She made no fuss over my advances.

The first successes came soon — I got into the Junior Sports School (which was a great honor), and in the same year, I won the regional championship for juniors of the 1st class. I had solo performances in children’s revues, and I performed a free skate during intermissions at interstate hockey matches. Unfortunately, I wasn’t lucky with a coach even in the youth sports school; the care of me and the care of prominent children with much fewer prerequisites and less talent were quite different. I was a little bitter, but the injustice could not deter me. Rather, I became somewhat self-taught. I watched Milena Kladrubská’s training with my eyes on the stopwatch and then learned from her. Milenka sometimes noticed me and gave me some advice. I was extremely grateful to her for every word. Since it is difficult to do compulsory skating without a coach, I used to have many big shortcomings in it. With time, I always improved my placements from the compulsory part and usually placed in the top ten. Toward the end of the third season, an important competition was held at the Winter Stadium, which was supposed to decide the inclusion in a higher-performing group. Dad gave me a crust of bread for luck. I put it in my pocket and was convinced that it would save everything I messed up. Unfortunately — the crust did not live up to expectations.

I performed the compulsories very well and placed second. During the free program, I lost everything I had gained — the illusions of reaching the coveted first place vanished. About halfway through the skate, when I was doing a double lutz, the edge of my skate came off due to some ice. Game over. I fell and cut my lower lip without losing my teeth. However, I was not deterred by this, I quickly jumped up and continued on in a second. Perhaps I would have finished the free skate, if it hadn’t been for the fact that they noticed in the music booth above that a creature that looked more like a butcher from a slaughterhouse than a figure skater was skating below. That’s why they stopped my music. At the children’s hospital, they then gave me eight stitches, wrapped my head in bandages, and I was afraid to show myself at home. Up until now, all the bumps and bruises I’d earned, I’d managed to hide mostly successfully, but this one could not be hidden. Right in the doorway above me, my mother wrung her hands, lamented, and programmatically declared that skating was over for good. She was very angry, I knew she was quite serious this time. I decided to make my parents think: I will study well, but above all, I won’t get a single note in the student book. It was a more-than-great resolution, for until then, not a week had passed without Daddy’s rod working. I regularly brought home notes of two types: “She’s restless, doesn’t pay attention” or “She’s unruly and talks during class.”

[…]

After all, my mother allowed me to skate then. Until I was fourteen, I raced around the Winter Stadium every winter. At the same time, I attended an advanced ballet school with the well-known choreographer Boris Milec. In addition, Mr. Milec had a very good command of rhythm, step, and acrobatics, all of which were also very suitable for skating.

In the winter of 1957, I had my first television appearance with Boris Milec’s school. It was a program for children, and coincidentally the gymnastics champion Eva Bosáková also performed there. I was thrilled with her performance. Since there was a long break between the rehearsal and the live broadcast, my mom brought plum cakes. She also shared them with my friends and offered them to Mrs. Bosáková, who was standing nearby. She liked them very much. They conversed a bit about some female topics. My mother, perhaps with a sixth sense, sensed that gymnastics might be the right sport for me, so she asked Eva Bosáková if she would take a look at me.

Mrs. Bosáková tested me first on the floor and then on the balance beam. I practiced on it for the first time in my life; if I hadn’t seen Eva Bosáková’s routine a while ago, I wouldn’t even know what was being practiced on it. So I tried the same thing and was shaking like an aspen. The coach laughed a lot and said to my mother:

“Mrs. Čáslavská, that girl of yours is a crazy one! Bring her to the gym with me sometime, she could be great! I train every day at the YMCA on Poříčí.”

MY BEGINNINGS IN GYMNASTICS AND EVA BOSÁKOVÁ

I was fourteen years old, and like most girls of that age, I started writing my secrets and unspeakable wishes in my diary. Debates. All those eleven years.

Eleven years… Mexico will be the end, the last in a long line of described pages. The end and the beginning — which is actually better?

Beginnings are perhaps always more attractive in everything. If someone put me back at the beginning of my gymnastics career today, I don’t know if I would find the courage to start again.

I’m almost at the end, and I have very mixed feelings. I know I’m tired, they are younger here, and they certainly have the same taste and ferocity that I used to have. And most importantly, they have a specific goal in front of them that they can focus on. It’s a nice feeling — to always have something in front of you and dive right into it.

In 1964 in Tokyo, I was also so great. I just wanted to be there and nothing more. I wanted to win the championship. I set my sights on Larisa Latynina and never let her out of my sight. Today I probably feel the same way as Larisa did then, the specific target to be shot down is now me. I have to admit that it’s not exactly the most pleasant feeling.

I flip through the diary several tens of pages back, I stand again at the beginning of all the glory and hard work.

March 13, 1957

…today I am the happiest creature under the sun, my mother took me to see Mrs. Bosáková in the gym. I also practiced on the uneven bars, and I can come again in a fortnight.

I started visiting Eva Bosáková once every two weeks, and so I slowly got to know the sport, the magic of which I had no idea before. I finally got to know the right thing, which corresponds to my interest and background, which my mother and I have been looking for for a long time. I fell in love with gymnastics and fell more and more into it.

At that time, Eva Bosáková was at the peak of her activity, she was traveling from meeting to meeting, from competition to competition, so she did not have the time or the conditions to pay enough attention to me. It often happened that I came to see her five times in a row, but instead of her, there was only a sign waiting for me: “Veruš, there will be no practice today, I’m leaving for training. Come in a fortnight,” or “Come tomorrow, I had to leave for a meeting.” I understood her situation, and I appreciated every moment she spent with me all the more. I was extremely grateful to her for taking me under her protection at all and for looking at me from time to time.

Then Eva went on a long-term trip to China with the national team. I didn’t want to come to terms with the fact that I wouldn’t see the gym for more than two months. I was afraid that Mrs. Bosáková would forget about me. I got it into my head that I had to somehow sneak into the gym. But to get there, I first had to overcome two hurdles. The first one was the doorman, at first glance a nice grandfather, he knew everything, and no one could fool him. He was nicknamed Sharp-Eyed and never missed a mouse. It was a big disadvantage for me. The second obstacle was the Sokolník, but I wasn’t so afraid of that because I already knew how to deal with it. I have often stood behind the glass door in front of the concierge since Eva’s departure, waiting for the right opportunity to slip through. Once I got into the gym by pure chance and considered it my biggest success of the year. After that, I repeated my secret escapes several times, but they didn’t work for me for very long. Once the porter caught me — he already knew me a little from handing out tickets — and called out to me: “Young lady, where are you going! Mrs. Bosáková is not here, so go home! You are not allowed to go to the gym without a trainer!” I wanted to save what I could and lied that I was only going to Sokolník with a message. So he let me in.

Sokolník was a prude, he never was soft with anyone. His weakness, however, was badges. Before he started complaining, I gave him my father’s most sacred badge, which he had in his collection and which I had conjured up for such a situation. It was Čechia Louna’s badge and he had once received it as a reward for being a successful goalkeeper. Mr. Sokolnik’s face lit up, he looked like a full moon, and he kept saying: “Well, that’s the thing, that’s the thing.” He immediately took off his cap, which had all the badges all over it, and ceremoniously stuck it in the most honorable place. He was such a fan that he didn’t even take it off in the gym.

Be that as it may, Čechia Louna saved me then, and I had the doors of the gym open once and for all. I trained alone and followed the adult gymnasts. Because I didn’t know fear back then, I started doing everything my wild imagination could think of. Before long, I knew many skills that caused trouble and instilled fear in others. Later I also realized that it would not be bad to transfer some special skills from the mat to the balance beam. I worked very hard on it. I started doing forward, backward, and sideways flips on the balance beam. The older girls just shook their heads at me. I even started doing saltos by myself. Once, when the gym was completely empty, I piled a bunch of mats on top of each other and started. That was the first time fear came over me. I was afraid that if I did something to myself, there would be no one to call for help, and this thought added to my terror. So I started according to the principle of teacher Ámos — from simpler to more complex. I must point out that it was the first time. Otherwise, I’ve always been very active in everything. I learned to do a salto by first doing a quick back handspring and trying to rest my hands on the ground less and less. When I felt ready enough, I plucked up the courage and quickly pulled my hands to my body in the air. I didn’t touch the ground. My first salto was born!

After that, I couldn’t get enough of flying through the air, I jumped endlessly, it’s a wonder I didn’t do saltos everywhere. I then came home exhausted and for the first time, I lost my appetite due to fatigue. It was a sign that I was starting to become a real gymnast with all the evidence.

April 1957

Regional championship of first-class teenagers

…my first gymnastics competition! I learned the routines five days before the competition, while the other girls had been practicing them for several months. Thanks to this hasty exercise, I got three bumps, and seven bruises, and then it was quite difficult to explain at home that I hadn’t just fought with anyone. Since Mrs. Eva was still in China, her friend, trainer Alena Tintěrová, led me to the competition.

I finished second. There was no end to the joy! I did not expect such success. The junior champion introduced me to gymnastics circles a little bit, and people started to know me. Not long after that, I completed another competition, in which a wider nomination for the 2nd Gymnaestrada in Yugoslavia was decided. I will hardly ever forget this competition; I have a truly original experience from it…

… Mrs. Eva was still away, so Mr. Schón, a trainer from Šumperk, offered to help me. On the balance beam, before a back walkover, I began to lose my balance. At the moment when I was already really far off the axis, I tried to save myself in a way similar to how a drowning straw is caught. In my case, it was not a straw, but the head of Mr. Schón, standing right next to the beam below me. In the foolish hope that I would inconspicuously bounce off the balance beam and gain the proper direction again, I rushed without thinking about this saving goal. I didn’t want to fall at all costs. But Mr. Schón flinched and I fell to the ground like a knapsack of misfortune. Touching the coach during the routine means losing one and a half points. I didn’t know that at the time, so I learned that during exercise you need to use your own head.

Even with that, I won third place. And then came the junior national championship.

15. June 1957

A good old acquaintance, Mrs. Stage Fright, crept into my fearful physical shell. This time she didn’t keep herself waiting too long. For the first time, I will be like a real competitor, with a number on my back! I’m thirty-three. Will it bring me luck?

With a small soul and shaking knees, I was getting ready to go to floor exercise. The announcer announced my name, I took a deep breath, plucked up the courage, and stepped onto the carpet. During the exercise, I had quite forgotten that my legs were shaking with fear; my nervousness had completely disappeared. People applauded me during the routine, it really encouraged me while I worked out on the carpet — well, not on the carpet exactly. I ended up somewhere in the corner on the parquet floor. The judges deducted two-tenths for stepping out of bounds, but I still got the highest score in the whole competition! But then misery came to the beam. I wasn’t very good at the balance beam, so I had a hell of a time practicing. However, when I learned that I was leading after two events, I was very happy. I swore that next time I’ll have to practice the balance beam a lot — then the nerves aren’t worth it in the competition. I performed a pretty good set on bars and kept my position. Right behind me, Jarka Smolková, an excellent vaulter, fought her way from third to second place. “Surely she will beat me now,” I thought, but I was ready to fight for my life. “I won’t give up easily now that I’ve fought for it step by step” I struggled terribly for the vault, I did extremely well. First gold medal!

Mom put it in a display case, and when someone came to us, she deliberately showed her great-grandmother’s rare mug, but I still knew that she wanted to show off the medal right next to it.

When Eva Bosáková returned from China, she was surprised at what I had accomplished during that time. She continued to devote herself to me, staying in the gym after her own strenuous training. At that time, she probably must have suspected that, with every kind word and encouragement, she was putting a louse in her coat, and yet she let me vegetate next to her. She later left my bars and vault to her coach Houdek, but I was able to continue training alongside her. Her presence had a great influence on me. I saw what the master’s training looks like, I realized that it is not enough to come to the gym once a week; my role model — Eva — literally worked hard every day. And this knowledge was the most valuable lesson that I took away from Eva Bosáková. Hard work and difficulties could not discourage or stop me. I loved movement, I couldn’t live without gymnastics. I was in the gym from morning to night, I could have slept there, and I still couldn’t get enough of it. I worked out with enthusiasm, but when the gym was empty, I only came into my own. I had no inhibitions, I practiced what I liked, and above all, I invented an awful lot. I invented combinations and new elements, danced in front of the mirror, and I didn’t have to be ashamed of my girlish and skeletal movement, I could enjoy it. At first, my parents were tolerant of my late arrivals, but later, when I could barely crawl home due to fatigue and was worthless at school, they didn’t let me go to the gym so often. Even the Sokolník somehow resented me — he always turned off the lights when eight o’clock struck in the evening. Later, my father admitted to me that they agreed to it together. There must have been some kind of badge involved, otherwise, I couldn’t explain Sokolnik’s willingness.

27. June 1957

Fourteen-day camp before the trip to Yugoslavia for the 2nd Gymnaestrada

I was out of luck! During the compulsory balance beam, my foot slipped during a jump, and I fell from a great height onto my tailbone. Wow, that hurt! I saw all the saints at that moment, I barely crawled out of the gym in pain.

The doctor didn’t give me hope for a quick recovery and kept giving me injections. I lay down for a few days, and when I felt a little numb, I was right back in the gym. At least I went to look at the others and I envied them terribly. Once, when I was leaving the gym, Jarka Matušková stopped me and said: “Věrka, I heard that you probably won’t be going anywhere. They say they don’t bring the sick ones with them.”

I was very unhappy about it — I worked so hard and now I’m going to stay at home? I’m going to try something else!

The same day, I appeared again in the gym with the others. With every movement I experienced hellish torment — Tantalus’s torment was certainly a complete romance against him. In addition, I had to look like I was incredibly ok, because the trainers would soon check me out. I secretly left the room of our shared dormitory and ran to the hospital. I endured for ten days — beam, injections, plastered smiles — on the eleventh day I decided to go after all.

For the first time, I will see the sea! After all, I’ve never been further than Olomouc.

July 10, 1957

That’s an experience! I don’t see where to go first, why are you surprised! I’m running around the city, peeking into shop windows, and I have fifty dinars burning in my hand, with which I would like to buy the whole of Yugoslavia, including its beautiful sea. Of my big dreams, only chocolate for my siblings, a colorful scarf for mom, and a toy box for dad remained. But I was so happy! I proudly sent out postcards everywhere, to classmates and relatives I hadn’t seen before. We lived in a nice girls’ dormitory and had an excellent group. There was always singing, lots of party games were played, we were constantly competing in something, one time who would do the highest somersault, the second time who would come up with the stupidest nonsense, who would find the courage to go there and say this and that, etc. In the evening, after rehearsals or performances, we were walking back to the dormitory to the lingering melodies of singing. The door creaked in the cemetery…

Once, we girls also wrote ten boys’ names on pieces of paper in our room, and before we went to sleep, we put them under the pillow. The groom will be the one whose slip you pull out first in the morning. It is said to fill in when you sleep abroad for the first time. In the morning, the name of Klečka, quite a handsome gymnast, appeared to me. Fourteen days ago, we made such a secret pact together, terribly serious and vitally important. I promised not to tell anyone, so in order not to break a strict secret, I will at least confide in my diary. He certainly won’t reveal it!

Declaration

“We, Věra Čáslavská and Karel Klečka, after a joint meeting on June 29, 1957, decided on the following statement:

As we are both united by a single interest, to achieve the best possible results in sports gymnastics, we will devote all our efforts to this interest, which we must increase to the maximum extent during the three years, so that we will participate in the XVIIth Olympic Games in Rome in 1960. In connection with this, we promise that during this preparation we will not be deterred by failure and will not be swayed by success. If one of us goes against this statement and leaves training for any reason, let him be cursed and the other party has the right not to look at him or greet him. The only excuses are illness or death.

This we solemnly promise with our signature.”

We took our statement dead seriously. In the same year, we both became junior national champions and participated in the national championship. Karel Klečka, like me, took sixth place in the championship. But I can’t get ahead of myself. I also had one completely exceptional and for me never-forgettable competition in České Budějovice: Czechoslovakia—Belgium.

[Budějovice is known as Budweis in German — like Budweiser beer.]

It was my first ever international competition, a baptism of representation. I was really looking forward to wearing sweatpants with the word Czechoslovakia and a lion on the jersey. I couldn’t contain my pride when I walked around the kitchen in a leotard, I kept sticking out my chest so that someone would notice me. I couldn’t wait for the competition. They played the national anthem at the opening and I was very proud. Czechoslovak television also came there, and it was this that was responsible for the exceptionality of my performance and also for these unforgettable experiences:

… at the moment when I was announced by the announcer to perform on balance beam, the guys from the TV let a flood of sharp lights from the spotlights onto the stage. Suddenly I saw neither the beam, nor the board, nor the judge — only scribbles, yellow, blue, and red marks in front of my eyes.

Since the announcer repeated my name for about the second time, I didn’t dare to hesitate any longer and like a frightened hare, I rushed somewhere in the confusion, where I suspected that the beam might be standing. When I hit the board, I told myself that I had already won half of it, so I really stomped on it and bounced off with full force. I flew through the air for a moment — flashes of color still in front of my eyes — but instead of landing on the beam, I managed to jump straight over it with a beautiful, buoyant leap. That freaked me out, but I didn’t go for a new mount. I tried at all costs to get on top of the beam to finally demonstrate what I had learned. I felt its smooth wood and swung up, but before you could say cobbler, I was back down and right where I started.

Wow, that was a piece of work! I haven’t performed anything yet and I already had two full deduction points. Then I finally got on the balance beam and started practicing. The routine was going pretty well for me, I was adding various unplanned tough elements and combos because I wanted to make up for the bad start at all costs. The biggest paradox was that I managed all the most difficult and risky elements smoothly and without a mistake, and then, in an ordinary, cheap, and schoolboy pose — literally from a squat — I fell down again. Third time. Although they say that everything good and bad comes in threes, I managed to make an exception and I messed up in fours. During the final somersault from the balance beam, I somehow mysteriously did not end up on my feet, as is usually the case. I simply sat down.

I only got about 4.5 points out of a possible ten, and I was glad that a zero was not shown on the judge’s sign. Then after the competition, everything came back to me, I cried. As long as I live, I won’t step on the balance beam again, I don’t have what it takes for gymnastics*, I’m terribly sick and I’ll go back to skating. I was most afraid of what Eva Bosáková would say to me. I was afraid that I would be fired. Such a shame! Four and a half points for the routine!

[*The Czech phrase literally translates as, “I don’t have the cells for gymnastics.”]

Still, I didn’t give up. Although I was already beating myself up, I was doing various spells, but the next day I continued with uneven bars and floor exercise. I fought like the lion on my jersey.

Good thing I didn’t throw in the towel then! Fortunately, I’m stubborn. That was my salvation.

I won bars and floor exercise. The judges awarded 9.80 points twice, I took fourth place. It sounded more like a heavenly song to me, but it was the naked truth.

November 22, 1957

Czechoslovak Championship — Women

… I am competing with the senior women for the first time in the all-around. Well, it will be a disaster again, it will be a shame again!

What a shame!? I’m only fifteen. I had to bring confirmation that I can exceptionally compete as an adult. I looked quite comical among the women. Not a fish, not a crayfish — not a woman, not a child. Besides, I was a ball, not even a gymnast in appearance. When I stepped on stage, no one took me seriously.

[Note: Medical certificates were common. The rules for gymnastics at the 1956 Olympics stated: “The gymnast must become 18 years old during the year of the competition and must be of the same nationality as the Federation to which she belongs, and she has to be a member of a federated association. A gymnast of 16 years of age, however, may be authorised to compete provided that she can produce a medical certificate to the effect that she is physically capable of withstanding the strain of the competition without any danger to herself.”]

Even I didn’t take my start for women seriously back then. The names Eva Bosáková, Týna Matoušková-Šínová, Věra Trmalová, Věra Hecová, and Libuše Houdková were too big a concept for me — I looked up to them with respect and admiration rather than having the courage to match them. I felt like a little intruder. As soon as it breaks out of his shell, it immediately rushes among the adults.

Eva’s coach, Mr. Houdek, actually came up with the idea that I would learn the compulsory routines. Once he also tried the compulsory bars for the world championships with me. To everyone’s astonishment, I practiced it correctly on the first try, and that immediately inspired him to prepare me for the adult competition. I found myself out of nowhere in an environment that depressed me rather than encouraged me, I had certain reservations about my early start in the women’s category, but I preferred not to express them.

However, it was a happy step towards further gymnastic development. If I had followed the age categories, I probably would have lost my performance, I would have been satisfied with my performance. That way, I always had something to catch up on and something to learn.

But I could not have known all this at the time.

Because I had my own philosophy for this start, I didn’t want to conquer the world or shine, I went through the competition completely calmly, without much embarrassment, I trained for my own pleasure. After the compulsory routines, I was among the best, I took fifth place. The all-around ended with sixth place for me, a bronze medal on bars, and a silver on floor.

The journalists made a big deal out of my position. I was full of contradictions; on the one hand, I was very pleased with the success, and on the other hand, it bothered me and was embarrassing that they overlooked many other adult and excellent gymnasts.

I know that it is difficult to understand my earlier inhibitions. Today, such an approach to competition is, to say the least, old-fashioned. But everything has pros and cons. Perhaps precisely because I didn’t want to become among the best at all costs, that I didn’t mentally beat myself up over the impossible, I managed to handle everything with ease. Many talented gymnasts have already paid the price for overly flamboyant determination. At the first chance — to get among the elite — they lost their heads and criticality and usually slowed down their progress. Too much stress and the desire to stand out at all costs are dangerous, violent, and often break a person’s neck.

Czechoslovak sport — March 10, 1957

“..her friend, fifteen-year-old Věra Čáslavská, came to see Eva Bosáková. She is a very physically gifted girl. Eva advises, explains, and helps her. And she says: “She will be my successor, she will one day defeat us all in a big way…”

It was the first time my name appeared in the newspaper in connection with gymnastics. I proudly brought the newspaper home and expected my father’s enthusiasm. Dad concluded that the journalists apparently had nothing to write about, and put the newspaper away as if he was no longer interested. Then, when he thought I wasn’t watching him, he read the article once more. He didn’t even know that his eyes were smiling.

In other competitions, mostly control and classification competitions, of which there were many, I always placed just behind Eva. There came a day when I felt that I was getting better. I was horrified! It felt like ungratefulness and betrayal for what she had done for me. I did not desire the highest apple. Didn’t she desire it? It probably wasn’t exactly like that… Actually, I don’t know.

Eva’s husband, who dabbled a bit in gymnastics coaching, once asked me why I don’t include forward and back flips on the balance beam, if I can already do them. I remember that I gave him a somewhat incomplete and confusing answer, but he gave me the answer to his question himself! “Because Bosáková doesn’t have them in the routine. Listen, Věra, if Mrs. Bosáková knew, she would be very sorry. Do what you can, and don’t make any excuses!” (Eva was always Mrs. Bosáková to me, I used the formal form for her.)

Today, when I look back on Eva’s relationship with me, I can’t call it anything other than classy. Eva was an exceptional person, with an unusual amount of generosity, a real athlete. Because she herself knew best that laurels grow from hard work, and she never received anything for free, she knew how to appreciate the efforts of others, and she did not underestimate anyone. I’ve never felt a grudge or jealousy in her like a woman against a woman, a competitor against a competitor.

I remember the 58th World Championship in Moscow. On the podium, in the middle of the sold-out auditorium of the Palace of Sports in Luzniky, the women’s event finals on floor were taking place. Eva reached the finals with the highest score and had a real chance to become the champion in this discipline. She finished her floor exercise as the last competitor of the seven finalists… The soft carpet muffled her final tumbling pass, Jan Seehák played the last chord of the melody at the piano… As soon as the applause greeting the new world champion subsided, shouts and calls were heard from the audience. I heard my name. The audience probably remembered the previous day, the competition on floor exercise. They probably liked my children’s performance, and that’s why they showed dissatisfaction with the judges that I didn’t make it to the finals.

[Note: Čáslavská’s performance at the 1958 World Championships became something of a legend in the Soviet Union. Read about it here.]

From the auditorium, the call to Česlavska was heard again and again! Česlávska Vjéra!, spilled from tribune to tribune, growing louder. In the end, most of the 18,000 spectators chanted: Czechoslovakia! Come on! The Czech Republic! Vjera! Vjé-ru!… It was endless. The calls of the announcer did not help, nor did the start of the ceremony, or the presentation of medals. The audience got it into their heads that they had to see me in the final no matter what, and they had no choice. They shouted, stomped, whistled — literally God’s permission. The organizers asked coach Slávka Matlochová to bring me. They promised the audience that I would perform at least as an exhibition.

However, I didn’t have a jersey with me. What to do? Eva came and offered me hers. Then the organizer came to tell us that the president of the international federation had forbidden me to perform. The reasons were understandable. Either way, Eva had risen even higher in my eyes.

Then, when we returned from Moscow, Eva and I were entrusted to the care of a new coach, Vladimir Prorok, a former European champion on floor exercise. Mr. Houdek somehow did not get along with the gymnastics leaders, he left.

The arrival of a new coach had a great influence on my further growth. Because he was in charge of more of us, he also trained Věra Trmalová and Libuša Cmíralová, he divided us into two groups. Eva practiced in the morning, I in the afternoon,

Eva and I became estranged. Mr. Prorok was very tenacious and goal-oriented, he wanted to achieve success in his new profession as well as in sports. My performances went up at a rapid pace. Of course, the difficulty of training has also increased considerably. Because I was not used to excessive load at that time, I had frequent injuries. They usually happened because I no longer had the strength to concentrate and control myself as much as possible by the end of the training. However, it was my own fault, because I secretly multiplied the training doses myself due to my overzealousness, my organism was not yet sufficient for them.

I completely lost contact with Eva, sometimes we didn’t see each other for a long time, and each of us was preparing for other competitions completely independently and separately. We became rivals, but not fierce ones. Later, Eva got into a big mental crisis, she knew that the moment would come when she would have to say goodbye, and she felt bad about it. They wanted to write her off. She couldn’t do the exercises and became terribly afraid. Everything: flip-flops, saltos, jumps — and I think a little bit of me too. I knew that until Eva Bosáková decided to leave, I would never strive for first place. I lacked the true ambition — to make it to the top. Second place was somehow enough for me; I knew that I wouldn’t have reached it without Eva.

Prorok brought me and Eva together again, he believed that my enthusiasm, taste, and effort would blow her away in training. Eva really started again with enthusiasm. I was happy that I could be of some help to her in return. When I accidentally came up with some “trick” on how to do an exercise better or how to learn it more easily, I always told the trainer my feelings very loudly so that Eva might take something from them. I didn’t dare to give master advice myself, but I wanted to help her. I realized that Eva partially accepted my feelings. She must have thought a lot about them.

“WHY ARE YOU TAKING THE CHILD THERE?”

May 25, 1958

Young Hope — Kyiv (Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Romania, and Ukraine)

… we have an excellent team; we understand each other fantastically. Ruda Kyznar, our new pianist, took the harmonica with him and occasionally lets himself be heard. Everyone immediately gathers around us, singing and dancing, it’s fun.

The competition started shortly after noon. We practiced outside at the stadium and it was terribly hot. The beam was as hot as a hot plate and bare feet could not stand on it. I didn’t do too well in the warm-up, but in the competition, I fought and did a pretty decent balance beam. On vault, I got 9.333 points, the most from our team, the first was Raya Gaplievskaya (Ukraine) — 9.75. I got the highest score in the entire competition for floor exercise — 9.80, and I shared first place with Gaplievskaya on bars. Overall, I took second place behind R. Gaplievskaya. Our team finished in second place behind Ukraine.

That was the last time I experienced some nice moments of real, carefree youth. I approached the competition with joy, just for fun, I didn’t care about anything. I stepped into the world with the right foot forward and with the courage of sixteen years. There, in Kyiv, I really admired the great Soviet hope, the Ukrainian Raya Gaplievskaya. She came to Kyiv straight from the Black Sea, where she was preparing for the World Championships together with other Soviet gymnasts. “She probably knows Larisa Latynina too,” I thought at the time, and that fact made her a demigod in my eyes. Raya Gaplievskaya was slender as a twig, and her legs were bronze. All in all, the whole thing seemed to me to be made of bronze. And how she performed!

“To be able to perform like that!” I wrote in my diary on 5/26/1958. I know I let out a deep sigh at the time, but it was gone right away. It just passed me by as if it didn’t even concern me. I was at an age where girls have other things on their minds and want to please boys. In Kyiv, I fell in love with a handsome boy, a gymnast from Bulgaria. It was my first platonic love, I was overjoyed at the time that maybe I wasn’t ugly and that someone could like me. We became very friendly and then, for a long time, several years, we wrote nice letters. Later I betrayed this friendship, today I don’t even know why. I was getting more and more pressed for time, so I started to train a lot. Apart from studies and work, I put all side interests out of my head.

Less than a week after Kyiv, the Women’s Republic Championship took place in Bratislava. The Slovaks cheered me on a lot, they created an extremely pleasant competitive environment.

After the compulsory routines, I was placed right behind Eva Bosáková, I kept second place with the optional routines, but I had a hard time.

I had a “window” during my optional beam routine. I just didn’t know how to proceed. My brain vibrated with hard thoughts on how to continue, I remember that I was sweating. In vain. I was getting more and more helpless. To save the day, I took three steps and flipped to the side, buying time. I believed that it would finally turn me on. But nothing! I wasn’t any smarter.

I was only able to take four steps and flip to the side. Nothing. Terror! I’ve never known anything like it. It was such insidious helplessness when a person cannot pick himself up, turn on his brain, or get himself together for anything in the world. I imagined the judges sitting at the tables and not knowing what to score. “I messed up their heads pretty well,” I thought, and I could imagine their faces quite well. I began to develop my idea in all its details, jokes, and more, and I began to laugh hideously. I stuttered, choked, and hiccupped with laughter. I felt like a fool, there were very few reasons to laugh. Down under the beam, I heard Lidka Švédová whispering to Eva: “What happened to Věrča? Is that normal?”

Toward the end of the set, I caught myself, finished the exercise, and didn’t fall. The mark of 8.75 was enough to keep second place. I was part of the team for the world championships and went with Eva Bosáková, H. Krausová, D. Tačová, L. Švédová, and T. Matoušková to a training camp in Nymburk.

July 4, 1958

I flew for the first time. The worst was when we were going up and down. A complete mess in my stomach, so the plane was not my cup of tea!

July 7, 1958

World Championship, Moscow

In the Luzhniki Palace of Sport, the announcer introduced individual nations and participants. He didn’t fail to point out that I was the youngest member of the championship.

We started on beam. It turned out quite well, even though we were very nervous. We performed much better on floor and vault. I put up a good score on bars, and I succeeded in the routine. Even the beginning, with a very demanding element of strength, which constantly gave me great difficulty, I managed to do well beyond the circumstances. After the compulsory routines, we were in second place behind the Soviet Union. We were very happy; we did not expect such a good position at all. It was the biggest success of the last ten years. Even the newspapers sang great praises, and the next day many supporters kept their fingers crossed for us to keep the regained positions for the colors of Czechoslovakia. Right behind us, with a very small difference (only 0.2 points), were the Romanian women. They went to Moscow with great self-confidence and even thought that they would beat the competitors of the Soviet Union. We did not rejoice too flamboyantly about our good position; we were afraid that everything would go wrong for us. Whenever I couldn’t contain myself any longer and showed the slightest hint of joy, the girls immediately shouted at me.

July 8, 1958

We are aware that it will be very difficult to maintain second place. The Romanian female competitors armed themselves with the best elements and routines, they prepared well-thought-out tactics. We started again on the beam, Dolfina was the first to go, followed by me, then Týnka, Lidka, Hanka Krausová. We did abnormally well, they were really good routines.

Evička was the last to step on the beam. She starts up and… she didn’t jump. We were afraid that her leg would come off. She starts up a second time and again nothing. I got a terrible fear for her. When she started for the third time, I thought I smashed my fingers. It worked, and Eva then performed an excellent routine.

After balance beam, the biggest weight of fear fell from us, and we jumped like chipmunks on the vault. Each one is better than the next. We got good scores.

When we moved on to floor exercise, the audience focused only on the carpet. They cheered us on a lot, especially Eva. She enchanted them with her exercise, but also with her impressive and captivating appearance.

Týnka went first, she practiced well, but she got a terribly low score. Only 9.2 points. It wasn’t hard to see why. The Romanian judge probably had the task of holding us back a little. The other girls only got a little more. The audience protested.

I was second to last, and I said to myself: “I will be careful about every step, every movement! It would be the devil if we didn’t get above 9.5 points!” At that time, I practiced really cleanly. The judges gave me a 9.6, but the audience chanted: too little, too little.

Evička went after me. The hall fell silent, and people stopped breathing. We weren’t breathing either. We stood squeezed in a corner under the stage, a little above us Eva was about to do the first salto in her life. We all knew her respect and fear of it. How many nerves has she experienced because of it? And tears and wounds! The first notes of her composition were heard. And Eva danced to the rhythm of the music. Will she flip? Won’t she flip? No one knew until the last moment. Not even Eva! She started running and a five-voice MUST! Was heard. She flipped! We saw her smiling back. She got a score of 9.8 points and made it to the finals as the best.

After that, the Romanians’ nerves quite failed — they were probably aware of our good results — three fell off the balance beam.

We kept second place and we were all extremely satisfied and happy.

In the all-around, Larisa Latynina won, Eva Bosáková was second, Tamara Manina was third.

I placed eighth.

After the World Championship, I had a fourteen-day rest, I finished my exams at the economics school. By the end of the year, the exercises more or less fell by the wayside, I had shorthand and typing tests ahead of me. In addition, I was looking for job placement, and Eva Bosáková also helped me. I got a job at the State Project Institute as a typist and earned four hundred and sixty crowns a month. Later, I was accepted directly by the Central Committee of ČSTV, I went through many departments — I was in the office, in the economic and legal department, in the sports gymnastics section, and I landed in the documentation department. Although I completed my high school diploma during my employment, I worked there for a very long time — until the middle of 1963, for 680 CZK per month; to this day I still don’t understand how I could get away with it.

One reply on “Čáslavská’s Early Years in “The Road to Olympus””

I’ve been looking the autobiography of Vera and this is the only thing I found.

Thank you very much for sharing.