Even though Čáslavská won the all-around and vault titles, and even though the Czechoslovak team defeated the Soviet team, the 1966 World Championships were still a low point for her — one that she hardly remembers. When she returned home from the competition, she received many letters, some of which were hate mail.

What follows is a translation of The Road to Olympus (Cesta na Olymp), Čáslavská’s 1972 autobiography. Here’s how she remembers Dortmund…

Note: You can read the main article on the 1966 World Championships here.

1966 Dortmund

What caused so much mystery and excitement to arise around Dortmund? What was Natasha Kuchinskaya actually like? What about the judges? What happened in Dortmund that made such a fuss that the press paid so much attention to it?

After Dortmund, the bag with letters was torn open. Every day the postman brought a package of them. Dad sorted them into necessary and less necessary and flooded the entire kitchen with them every evening. Everywhere one looked, there was a letter — on the table, on the chairs, on the sideboard, and also in the large laundry basket.

Dad counted over 8,500 “Dortmund” letters, including this one:

“Go to hell, you old beauty! Who should keep looking at your drowsy and dull face? Don’t get in the way and let the young one go. If you don’t get away from it yourself, Kuchinskaya will soon wipe your eyes.”

[Note: You can read about the 1966 podium controversy here.]

When we were sitting in the waiting room at the airport before our flight to Dortmund, a gentleman brought me the morning edition of the newspaper. The Soviet press published a statement by the all-around champion of the USSR, N. Kuchinskaya from Leningrad:

“I want to share the gold medals with Čáslavská” And she prophesies further: “For me, first place on beam and floor, for Čáslavská on bars and vault.”

Similar proclamations have always done me rather well. But before Dortmund, I reacted quite differently than usual. I wasn’t in my skin. Of course, the injury from Brazil — a sprained left elbow — contributed in no small measure to the poor mentality. The Brazilian doctor who first treated my arm didn’t believe I would ever exercise again. If it weren’t for the excellent doctor, I would have had a hard time preparing for Dortmund. He performed real miracles. But I still lost a large part of the preparation. And since then, I don’t trust myself that much either. I was full of depression and insecurity, my arm was still hurting, it even gave out on its own during exercise, and I messed up even the simplest exercises.

I was like a frightened hare. The older a person is, the dumber he is.

And then came Dortmund.

First, there were men’s competitions. Endo Yukio, a crown prince from Prague, Olympic champion from Tokyo, and the biggest aspirant for the world title, lost. He was defeated by a young gymnastic hopeful, Voronin of the Soviet Union. I felt sorry for Endo as he sat slumped in his chair after the competitions. At first glance, it was obvious that the defeat hurt him a lot. Without wanting to, I also applied it to myself.

Dortmund’s hall has not yet changed into a woman’s dress, the craftsmen were still making the final adjustments, but behind the scenes, in the associated training gyms, it was already chattering since morning. It was liveliest when some of the stronger teams appeared in the gym. Soon even the audience recognized that they were Czechoslovakia, the USSR, Japan, and the GDR. Applause erupted here and there, and spy cameras whirred.

We sat, already in tracksuits, in the hall and waited for some equipment to be made available.

What does a girl who claims to be a winner really look like? My eyes wandered to the pea-green tarpaulin for the commoners. Young girls, only two familiar faces remained — Larisa Latynina and Polina Astakhova. And also Larisa Petrik — I met her last year at the European Championships in Sofia. At that time, even before the competition, she was declared by the Soviet press the greatest aspirant for the European Championship Cup.

[Note: You can read about Petrik defeating Latynina in 1964 here, and you can read an interview with Latynina about her defeat in Tokyo here.]

Marienka Krajčírová, as if reading my thoughts, pointed to a girl with a big bow in her hair tied in a ponytail. She spotted us and walked past. She knew how to present herself to command the proper attention and respect.

… Slávka called us together and assigned each one of “her” apparatus: “Marička, you and Bohunka will go to the bars and really spin it up there!” Let it fly!” Marička “slammed” the bars with great enthusiasm. Slávka happily nodded her head, smiled, and said: “There’s Marička! You don’t have to say anything twice. She will do a set or two until her eyes cross.” She turned to Opička (Jindra Košťálová’s nickname for her fantastically flexible legs, which she can really put behind her ears) and to Dada: “Carry yourself there like dolls, the whole world is watching.” She assigned floor exercise to me. They are my favorite discipline.

Like a thirsty animal, I flew past the observers and after two flip-flops I did a perfect salto with a full twist.

The long-awaited Thursday, September 15, is already here, and with it, the competition. We started in the morning group, and since there was no team in front of us that was able to drag up the scores from the low average, the judges were betting on us — practically on all four apparatus. Nevertheless, we all performed calmly and with confidence — none of them fell and did not ruin anything. Only Marička had to repeat her balance beam, but then she performed well. We finished in less than two hours, happy to be done with the compulsory routines that we worked so hard on for so long.

[Reminder: In 1966, gymnasts were allowed to repeat their compulsory routines. Here’s the 1964 Code of Points.]

We did everything we could, and we were satisfied. Since there was no way to compare yet, we didn’t worry about the not-so-high scores. In the evening, we sat comfortably in the stands and watched the opponents.

We were surprised by the Soviet team’s performance. Often, their performance was not clean and precise, as was always the custom for them. Even the girl, who had been told so many times that she would beat me, was somewhat insecure during the compulsory balance beam routine, she was afraid to peel herself off the beam on the jump, and she even failed the prescribed handstand with leg switching.

[Note: You can read the text for the 1966 compulsories here.]

Unfortunately, the judges gave incredibly high scores for these exercises as well — we couldn’t understand them at all.

Compulsory routines are boring for competitors, judges, and spectators. We dedicated many hours of practice to them — we learned the maximum positions and the perfect technical execution. It was tiring, tedious work, we expected a lot from it. And suddenly — everything goes unnoticed; routines, which do not have this [i.e. maximum positions and perfect technical execution], are put into the lead. We were very sad about it.

What are all the calluses and bruises for?

What’s the point of tedious, ant-like work?

Why the endless hours of fumbling and searching?

After the compulsory exercises, we are 363 thousandths behind the Soviet team, the Japanese women are third with a slight difference of 101 thousandths of a point. In the women’s individual competition, I am first ahead of Kuchinskaya.

Since Saturday morning [i.e. the morning of the optionals portion of the competition], I have been worthless. As early as half past seven, the Japanese women were performing, followed immediately by the USSR team.

What happened to them was what happened to us in the compulsories. Competing so early in the morning is no honey.

[Note: Čáslavská is suggesting that the scoring starts out lower in the day and then progressively gets higher.]

I couldn’t stay in the hotel; my nerves were acting up anyway. I went to watch the competition. I couldn’t find peace even there. When anyone asked for an autograph, many people felt it was their duty to tell me what they thought about the unfair judging. I’d rather go to the gym to train on the beam. I tried to put yesterday out of my head.

Despite everything, I ate beef with mushrooms at noon and went for a walk.

I wanted to sleep, but I couldn’t…

The evening’s opening dragged unbearably. There was noise from the competition floor, the audience rioting over the low score for the American Doris Fuchs on bars. Already in training, she amazed us with the difficulty of her composition and risky elements, she just deserved to be in the final. The chants and protests of the audience were of no avail. In addition, the FIG president has warned that the organizers will clear the hall if similar issues are repeated.

We were not pleased with the delay in the program. We had long been warmed up and ready to start; it was not easy to keep up the pace all the time. We had to constantly move, jump, bend over so we wouldn’t get cold, and force ourselves to the pre-start state again and again.

We lined up five times already during the hour. For the sixth time, neither of us believed it.

Finally, we marched out, the public was dissatisfied, and many left in disgust.

We started on bars. There was strength in us. The desire to be satisfied had freed us from fear and anxiety. We fought event by event for every hundredth of a point and caught up with the Soviet female competitors.

The real drama happened on vault, during the last discipline! Everyone knew what was going on. The differences were calculated only to thousandths of a point. Most of the audience crumpled a piece of paper on their laps, adding and subtracting. Every now and then, acquaintances told us some result, but each time it was different. Everyone got something different.

The first vaults, Bohuna and Jindra, were very good. It seemed that we might even win. Our coach Slávka Matlochová’s voice was shaking. Is it enough to equalize the lead of the opponents? The fifth, Marienka Krajčírová, also reduced the point difference. After her, I was preparing to vault. It was clear to me what was at stake. Perhaps I have never felt such responsibility before. Gotta vault to 9.7! My soul clenched at the thought that I wouldn’t be able to do it. How would I explain it to the girls, because even they expect me to vault to 9.7? The tension grew by the second. Everyone knew that the championship title of the Soviet team hung in the balance, that it depended only on this vault. Even the judges knew it. They knew that the seven would decide everything behind the nine.

Seven [i.e 9.7] means victory. More people wear it on a locket, believing that it brings good luck. I would very much like it to not remain just a medallion, a symbol.

The all-around world champion of 1962, Yuri Titov, put down his inseparable movie camera and checked his scores again. He had a heated discussion with the coach of the Soviet team, Sofia Muratova. All the female athletes of the USSR were also sitting there. Natasha Kuchinskaya quite in front. Even now, when many doubted her victory, she looked confident. It was clear from her expression that she knew her stuff. I already knew mine!

I vaulted to 9.733, and the Czechoslovak team, after 14 years of continuous hegemony of the Soviet Union and again after 28 years in the history of sports gymnastics, won the world championship.

[Note: The Czechoslovak women won the team competition at the 1938 World Championships. That’s why Čáslavská refers to 28 years in the paragraph above.]

The keyboard tapped the number 0.038 and the tubes sparked. In our macro world, it is quite a tiny, barely perceptible grain. But on the scales where gold and silver are measured, even this breathing is a thousandth and first.

The Czechoslovak flag flew.

And then once more, on the all-around podium.

No one could take away the title of absolute world champions in the team competition and mine in the all-around.

But the next day in the finals…

Vault. I won another gold medal for Czechoslovakia.

I performed the uneven bars with great enthusiasm and spark. I performed two full turns in a row — a combination incomparably harder than the Tokyo “ultra C.” After me, Natasha Kuchinskaya went. I’m not going to judge her performance, I’m just going to say, completely dispassionately, that she didn’t deserve a gold medal on this apparatus. The gold medal for uneven bars should have belonged to Doris Fuchs from the USA. We were all surprised by Kuchinskaya‘s victory, especially herself.

I will never forget this announcement of the winners. All six finalists took the stage. The announcer called out the first name. Natasha Kuchinskaya. I was waiting for the second name. It started with quite a different letter. There must have been a mistake, surely everything will be explained. Neither the second nor the third name was mine.

My throat got tight.

Before the Japanese Tsurumi Taniko* left for the podium, she turned to me and apologized confusedly — that she was sorry, that it wasn’t her fault, so that I wouldn’t be angry with her. I wanted to smile at her, but the corners of my mouth started twitching. The tears wanted to come out so much, that I choked and swallowed at the same time. “Cry, but be careful!” — I remembered the words of our father.

[Note: The name is incorrect. Mitsukuri Taniko finished third.]

Immediately after the bars were announced, there was a five-minute warm-up on the balance beam. I don’t even know if I even warmed up. The first two competitors finished the competition, and after them, it was my turn. What and how I performed, I don’t know, I don’t know anything, only that I made a mistake during the last pass when flipping forward.

The winner’s podium once again belonged to Natasha Kuchinskaya.

I stood on the second step. Kuchinskaya cheerfully congratulated me on my success.

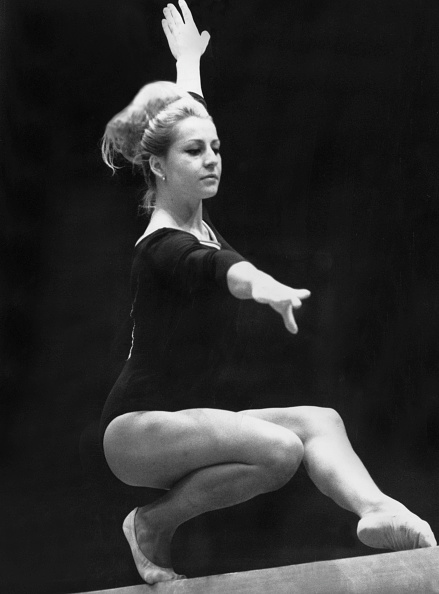

We solemnly marched around the audience on the balance beam. Natasha Kuchinskaya, me, and Larisa Petrik.

And there is floor exercise. The gong was struck. I desperately tried to pull myself together. I’ll go for it! I won’t give up!

The soft and delicious theme of Smetana’s melody connected me to home. The Vltava gave me new strength. Everything was carried away by stormy rapids with round-offs, flic-flacs, and saltos — I was exercising easily and non-violently. The Vltava came in very handy for me, it never came out of my soul as much as this time.

I hadn’t had time to take a deep breath and there were already scores on the judges’ boards. The coach complained to the head referee, Marná. Natasha Kuchinskaya won again.

What actually happened in Dortmund?

More on 1966