What does it feel like to be in the lead after the first day of competition? And what does it feel like to hang onto that lead to win the all-around title?

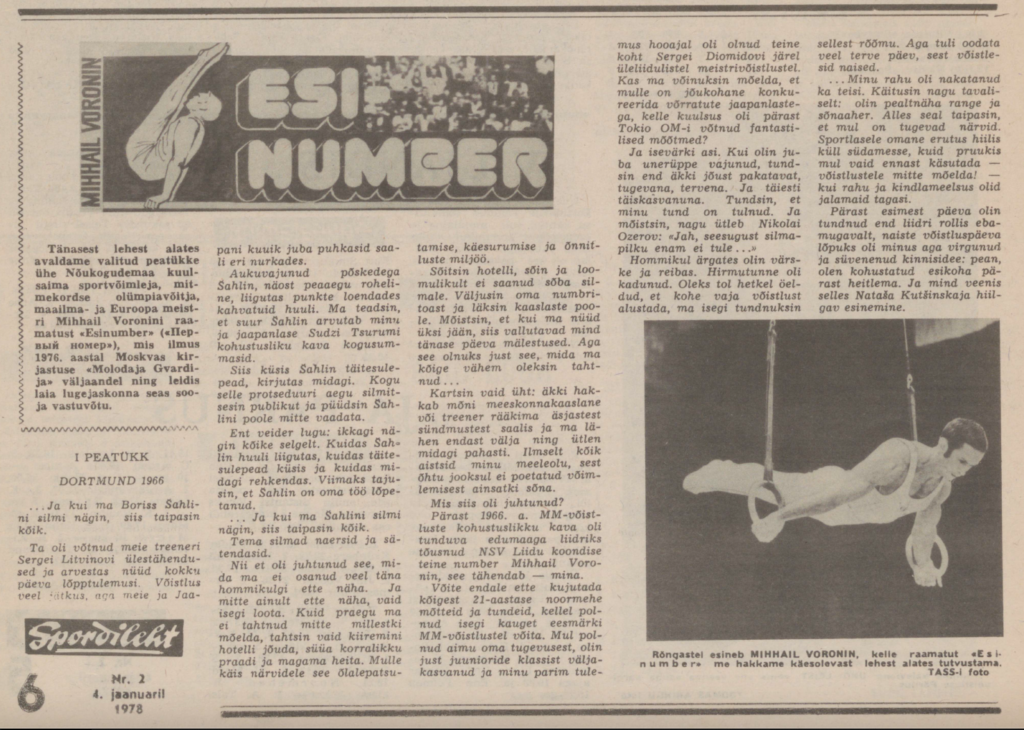

In his book, Number One (1976), Mikhail Voronin recounts what he was thinking and feeling during the World Championships in Dortmund, where he won the all-around title.

In addition to insights into his inner state, Voronin’s autobiography provides a few details that were not reported widely at the time. For example, the Soviet team had a new coach on the floor during the optional competition in Dortmund because the other coach was too nervous during the compulsory competition. And there are gossipy tidbits like this one: Sergei Diomidov had a fight with his coach before the 1966 World Championships, which made him want to quit the sport.

Below is a translation of the first chapter of Voronin’s book.

Note: The first chapter of Voronin’s book was translated into Estonian for the newspaper Spordileht (published January 4 and 6, 1978), and I have translated the chapter from Estonian into English.

NUMBER ONE

Starting from today’s newspaper, we publish selected chapters from the book “Number One” (Первый номер) by one of the most famous gymnasts of the Soviet Union, multiple Olympic champion, world and European champion Mikhail Voronin, which was published in 1976 in Moscow by the publishing house “Molodaya Gvardiya” with a warm reception among a wide readership.

CHAPTER I

DORTMUND 1966

… And when I saw Boris Shakhlin’s eyes, I understood everything.

He had taken the writings of our coach Sergei Litvinov and was now tallying up the final results of the day. The competition continued, but we and the Japanese sextet were already resting in different corners of the hall.

With sunken cheeks, almost green in the face, Shakhlin moved his pale lips as he counted the points. I knew that the great Shakhlin was calculating the compulsory routine totals for me and Japan’s Tsurumi Shuji.

Then Shakhlin asked for a fountain pen and wrote something. Throughout this procedure, I was staring at the audience and tried not to look at Shakhlin.

But strangely: I still saw everything clearly. How Shakhlin moved his lips, how he asked for the fountain pen and how he was calculating something. At last, I sensed that Shakhlin had finished his work.

… And when I saw Boris Shakhlin’s eyes, I understood everything.

His eyes were smiling and sparkling.

So now something had happened that I could not have anticipated even this morning. And not only anticipate, but even hope. But right now I didn’t want to think about anything, I just wanted to get to the hotel faster, eat a good meal, and go to sleep. The environment of pats on the back, handshakes, and congratulations was getting on my nerves.

I drove to the hotel, ate, and, of course, could not fall asleep. I left my hotel room and went to see my friends. I realized that if I am left by myself now, I will be overwhelmed by the memories of today. But that would have been what I least wanted …

I was only afraid of one thing: maybe a teammate or coach would start talking about recent events in the gym hall and I would lose my temper and say something bad. Everyone probably sensed my mood, because during the evening not a single word was spoken about gymnastics.

So what had happened?

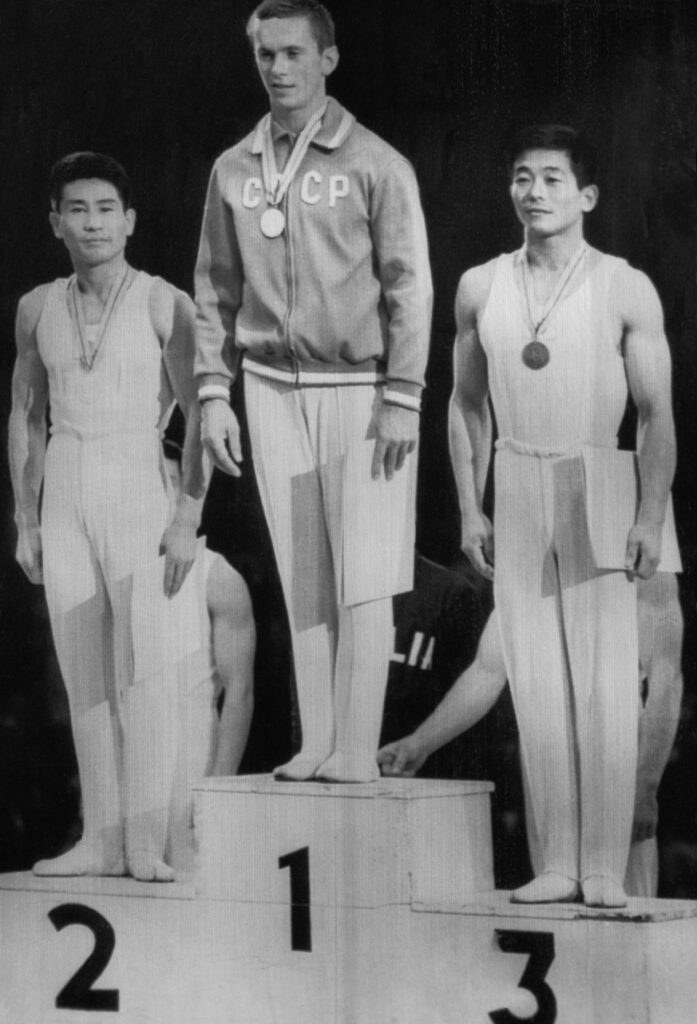

After the compulsory routines of the 1966 World Championships, it was the second person on the USSR national team, Mikhail Voronin, who became the leader, that is, me.

You can imagine the thoughts and feelings of just a 21-year-old young man who didn’t even think of winning the World Championships. I had no idea of my own strength, I had just graduated from the junior class, and my best result of the season had been second place behind Sergei Diomidov at the All-Union Championship. Could I have thought that it was within my reach to compete with the great Japanese, whose fame had reached fantastic proportions after Tokyo Olympic Games?

When I had already fallen asleep, I suddenly felt invigorated, strong, and healthy. And completely grown up. I felt that my time had come. And I realized, as says Nikolai Ozerov: “Yes, such a moment will never come again…”

When I woke up in the morning, I felt fresh and energetic. The feeling of fear was gone. If it had been said at that moment that I had to compete immediately, I would have even felt happy about it. But we had to wait a whole day because the women were competing.

… My peace had infected others as well. I behaved as usual: on the surface, I was strict and taciturn. Only then did I realize that I had strong nerves. The excitement typical of an athlete was creeping into my heart, but I only had to tell myself not to think about the competition! And the peace and determination returned.

After the first day, I had felt uncomfortable in the role of leader, but by the end of the women’s competition day, I was exhilarated and obsessed: I must; I am obliged to fight for first place. And I was convinced by Natasha Kuchinskaya’s brilliant performance.

How bravely our girls performed! They were not scared of the huge authority of the Olympic champion Věra Čáslavská. Or maybe because of their youth, our women did not understand that it is not yet within their power to offer equal competition to the Czechoslovak gymnast? Oh no! I could see the thirst for winning in their eyes…

The mood of the team was poor. Even Natasha’s glowing performance did not inspire the boys. You could feel that Čáslavská would not back down from her position. Moreover, the Czechoslovak delegation threatened to snatch the gold medal from our girls.

But our situation was even worse. The Japanese had torn away from us strongly and catching up with them was out of the question. I was in the lead in the individual event, but only the Japanese were chasing me.

Diomidov was especially struck. He was number one, he was relied upon and believed to be the only one who could get a medal. But it didn’t work for him, something was wrong in his whole being. Sergei came to the World Championships depressed. He had just had a conflict with coach [Konstantin] Karakashyants, which got him so upset that he skipped training and thought about giving up gymnastics altogether. However, Diomidov was able to get back into shape quickly. But the haste had taken its toll: he lacked stamina and performance It seemed as if nerves and physical fatigue had pressed down his strong shoulders…

Boris Shakhlin, the great Shakhlin, was assigned to the team as a mediator. These were his last competitions, as were Yuri Titov’s. These two aces were on their way out, and in their last competition, where they performed routines that were by then out of fashion, they did everything they could to help us youngsters compete with the Japanese for the medal.

It did not work out.

Everyone was hoping for a miracle. I felt that my leadership position was like butter for our three veterans Boris Shakhlin, Yuri Titov, and Valeri Kerdemelidi. Our tour group of specialists was like a gunpowder cellar, ready to explode at the slightest spark of hope. Senior coach Valentin Muratov and coach Sergei Litvinov tried to keep calm but in vain. Both had jittery nerves.

In such an atmosphere began the day of optional routines, which was to decide the fate of the BIG GOLD MEDAL.

WHAT IS FAME?

… So many years have passed, but I still vividly remember all of the details, every conversation that took place that evening, the evening before the most important day of my life.

What is fame? “Nothing but smoke,” said Gustave Flaubert. Did I desire fame or recognition? What was I striving for in my first World Championships? What kinds of feelings were pushing me to act and behave as I did?

I am asking myself: “Who would I be if I hadn’t started practicing sports? After all, sports made me famous, made me a person.“ I ask myself and don’t get an answer. Perhaps what will happen to a person in his life is predestined from birth.

Anyway. If I were not the world champion in gymnastics, I would have been a member of the all-Union team for several years. What would have changed? If I hadn’t started gymnastics, maybe I would have made progress in hockey or soccer (I was already quite good at these).

But enough of sports. At school, I liked math, especially geometry. Where would have science taken me? Who knows…

I am glad to have devoted my best young years to a hobby that completely occupied me.

Sport. A pastime? Hobby? A waste of time? No, far from it. I will always remember the foreign column published in Sovetsky Sport, titled “Citius! Altius! Fortius!“ The very same “Faster! Higher! Stronger! ” are the three Olympic measures of sport. But sport is even more multifaceted. Sport is also human destiny, an echo of social and economic phenomena, a companion of peace and friendship.

Yes, sport is more multifaceted. Creating a harmonious personality is a matter of national importance. Taking care of people’s health is the goal of our party and government. It is the duty of every Soviet athlete to win in a fair sports competition.

What does sport give a person? With what does it still charm generation after generation? Is it only the intense feelings that one experiences on the sports field?

Sports achievements expand our perception of human capabilities. An athlete who surpasses many rivals or achieves phenomenal results in running, jumping, and lifting, is in some ways proving that each of us has admirable qualities and endless capabilities. (To be continued.)

[Continued]

“Many of my strongest beliefs about human morality and duty are related to sports. Following and voluntarily accepting the jointly developed rules of a game, love of justice, and sense of duty, this is what sport gives to a person.”

So has said the French writer, Nobel Prize laureate Albert Camus.

Yes, sport also means moral growth. In general, bad people do not last long in sports; the united sports family throws them out of their ranks. With the help of sports, a new type of person, ideologically strong and harmoniously developed, is cultivated. Modern sport is unthinkable without deep knowledge; great results come not only from physical efforts. They become part of spiritually rich, thinking people.

And that is why I feel that people need me. If you feel proud of the athletes, you also feel proud of the country where they grew up; you feel proud of the coaches who have guided them to the podium.

… But that night in Dortmund, I didn’t have time to dwell on the meaning of life. If I already had the opportunity to become a world champion, I had to use it to the fullest extent. I knew only one thing: the title of all-around world champion was needed not only for me, the leader of the first day. This title was primarily needed for our Soviet gymnastics, for everyone who watched our performance at home.

THE HAPPIEST DAY

Competitions in optional routines started at 8 am. I believe you realize that this is an unusual time. The routine had to be changed on the fly.

I shared a room with Valery Karasyov. We woke up at 5, did some morning gymnastics, and were the first to arrive at the competition venue. But it was terribly cold there. The metal parts of the gymnastic equipment were frosted. Then the other boys arrived, and we warmed up for an hour and a half instead of the usual 30 minutes: there was no way to beat the cold.

At precisely eight o’clock, Boris Shakhlin was the first from our team to go to the horse: he started. In the team competition, first place was already decided; the Japanese had fought too hard. And now each of us tried to get the maximum score to get to the finals, where the winners of the individual disciplines are determined.

Shakhlin got a low score on pommel horse; he made some serious mistakes. Yuri Titov was the second competitor in the competition; he also failed on one element. The third to compete was Valeri Kerdemelidi. He couldn’t stay in the saddle either.

“What a great start!” I thought and looked at the complacent Japanese. “This is a chain reaction that can pass on very fast… Need to do something about it quickly …” I decided to tone down my combo and leave out one difficult element at the end. It seemed more peaceful that way…

At that moment I did not consult anyone, there was simply no time. I waited for my turn and noticed with satisfaction that Karasyov and Diomidov were able to handle their routines well.

I did brilliantly in my routine. I finished and looked at the judges. And only then did I remember that I had also performed the element I was going to leave out. Apparently, everything had been learned so thoroughly that I operated like a machine.

I got 9.85 on rings. My trademark is rings, so to speak. I could see that everyone liked it, and the audience was thrilled. If I’m honest, I also liked this apparatus.

That day the coach was Yevgeny Korolkov, he was replacing Sergei Litvinov. The latter was terribly nervous on the first day, and that’s why the head of the delegation asked Korolkov to come.

His calm manner and sobering words had a good effect on me. And then Korolkov came up with a little psychological trick: before going to the apparatus, he carefully adjusted the suspenders of my pants, which were already perfectly fastened. A seemingly insignificant detail, but it somehow helped me to focus on the upcoming routine.

After vault and parallel bars, where I also had high scores, I felt relatively confident. No Japanese, neither Tsurumi Shuji nor Nakayama Akinori, could catch me. Only a fall or some other unforeseen incident could have prevented me from finishing the competition calmly.

The Japanese were in a very good mood, they already had the gold medals in their pockets. They even frolicked on the floor, smiling while doing their routines. But our faces were stern, even grim.

And then I felt aggravated. Do the boys really not believe in my victory? Are they really afraid I might screw up?

Korolkov said: “Misha, I advise you to leave the twist out on the high bar. It seems to me that you don’t have a good enough handle on it yet. Why risk it, if the program is quite difficult even without the twist.”

In order to lift the spirits of my companions, that is what I did. I replaced the twist with a pretty classic dismount. I see our men’s smiling faces, they understood the joke. However, the performed dismount is considered too easy and the Japanese got really angry. Is Voronin making fun of the judges? I got a slightly lower score than planned, but I could already afford such a luxury.

And then, when the last optional routine of the all-around competition was coming up, I suddenly got nervous. What if I get injured during the warm-up? But maybe I slip while performing acrobatic elements? Then, suddenly…

This rush of anxiety was due to the fact that one of our tourists shouted to me or to all of us: “For Voronin, 8.6 points is enough. He will still be a champion!”

It was this calculation that knocked me out for a moment. I don’t need to know those numbers! I need to get at least 9.6. If I start thinking about the worst option, I will definitely fail…

…I finished the routine. Turned to the judges. There were no major mistakes. That I knew So the score had to be more than 9,0. So … Therefore…

For some reason, I repeated those two words to the beat of my steps. I couldn’t resist and ran.

I felt a great surge of strength.

I wanted to do it again.

No, three times!

I saw our boys clapping and everyone was smiling.

I heard our tourists chanting: “Vo-ro-nin! Vo-ro-nin!”

Then I remember nothing. To everyone who congratulated me, I said: “Thank you, thank you…”

And when Stanislav Tokarev from Sovetsky Sport approached me and asked how I was feeling, I managed to squeeze out these words with great difficulty: “Very happy, very tired, very hungry…”

We ran to get lunch. I had already calmed down. I drank juice but didn’t want to eat.

Right there, I was informed that the order of a merited master. of sport was waiting for me in Moscow.

NEW WAVE

My victory was not as unexpected as some thought. This was the result of the consistent development of gymnastics in the Soviet Union.

When Soviet gymnasts won both individual and team events at the Helsinki Olympics [in 1952], it seemed that our era had arrived.

This opinion was well-founded.

The Helsinki gymnastics tournament showed the complete superiority of Soviet athletes. Both in terms of the difficulty and performance of the exercises, our gymnasts greatly surpassed their foreign competitors, the most dangerous of whom were the athletes from Switzerland and West Germany.

But the hegemony of our male gymnasts lasted only eight years. At the Olympic Games in Rome (1960), the Japanese team won the gold medal. Since then, our men have almost always come second in major international tournaments.

The progress of the Japanese gymnasts, their wide attack on our positions, could be compared to a typhoon, which, however, was challenged. The Japanese did not manage to climb to the very top of the podium. Boris Shakhlin, Yuri Titov, and then I managed to win the title of all-around world champion.

On our team, there was a change of generations. Already in 1964, it was always said that our entire team had aged and that it needed to be supplemented with young athletes. And it became clear at the Tokyo Games that change was essential.

At the all-Union Championships held in Kyiv in December 1964, it happened. Then for the first time, the audience saw Vladimir Soshin, Valery Karasyov, and me, as well as Natasha Kuchinskaya, Larisa Petrik, Olga Kharlova, and Zinaida Druzhinina competing among adults. The new wave was quite powerful. The young generation of Soviet gymnasts rose to the heights of sports.

The young demonstrated new exercises well. The first competitions in 1964 turned out to be a turning point in our gymnastics. But their wings were not yet strong enough for the World Cup, and the team was made up of the veterans Shakhlin, Titov, Kerdemelidi, and youngsters Diomidov, Karasyov, and Voronin. Only Diomidov and I managed to win a medal in Dortmund.

THE BURDEN OF A CHAMPION

The 1966 World Cup competitions were dramatic. A lot happened in the course of these four days! No gymnastics competition had ever produced so much joy and disappointment together.

Decide for yourself. I become the all-around champion and bring joy to our team. But the team loses to the Japanese once again in frustration. Voronin and Diomidov get gold medals in individual events. Veterans Shakhlin and Titov are sad to say goodbye to gymnastics. Our women’s team loses in despair. The loss of the women’s gymnastics crown is a disaster. Kuchinskaya’s silver medal in the all-around is a new burst of hope. The celebration of Kuchinskaya’s three golds in the individual events…